- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

Corona-Socio-Legal Challenge with Sweden as an Example

Håkan Hydén*

Professor in Sociology of law, Lund University, Sweden

*Corresponding author: Håkan Hydén, Professor in Sociology of law, Lund University, Sweden

Submission: December 18, 2021;Published: January 19, 2022

.jpg)

Volume10 Issue2January, 2022

Abstract

Society is challenged by a virus that threatens humanity, which calls for intervention in private spheres belonging to different policy areas. As a result, the regulation becomes like a patchwork quilt without normative consistency. The regulation is ad hoc. Sweden has initially relied on influencing people’s behavior through norm creation and not legislation, partly being forced to since the constitution does not leave room for exemption laws in the same way as other countries. When it comes to formulating policy, the expert authority, Public Health Agency, has a central role. Democracy is replaced by meritocracy. Legality presupposes legitimacy in order to function. This is a balancing act between formal and substantive legal certainty. As a general conclusion, legal regulation is most effective when legality and legitimacy flow together. However, where these meeting points can be found in practice varies with the nature of the problem.

Keywords: Law; Norms; Legality; Legitimacy; Covid-19

Abbreviations: SARS-CoV-2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2; EMA: European Medicines Agency

Challenges

Background

In China, December 2019, cases of pneumonia were found to be due to a new and previously unknown coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, hereinafter referred to as corona. The new coronavirus is named after the related virus SARS-coronavirus. The disease caused by the new coronavirus is called COVID-19. The new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, has the same genetic makeup as the SARS-coronavirus and coronavirus found in bats. The new coronavirus presumably comes from an infection that has spread from animals to humans after jumping across species1. Another theory is that the virus has been transmitted from animals to humans for some time and that there have been several people who have been infected. After that, the virus has started to spread from one person to another. Already at the beginning of March 2020, it was clear that the corona infection had spread all over the world, a pandemic was inevitable2. The corona pandemic has posed numerous socio-legal challenges. There are several reasons for this. The background to this can generally be argued to be as follows. Law can be seen as a standardized policy [1]. It concerns standardized solutions to different societal problems. Instead of the political system having to be enrolled every time different value-based and normative positions are required in society, law contains standardized solutions to frequent problems in society [2]. The more conflict-ridden these problems are and the more often they occur, the greater the reason to expect the solutions to be juridified [3]. Thus, law can be argued to unburden the political system by leaving decision-making in sensitive matters to courts and authorities. These standardized solutions are based on assumptions that require relatively stable norm solutions in order to be successful. However, this relationship does not characterize the regulatory problem associated with corona as a socio-legal problem.

Footnote

1The risk of infection between animals and humans is regulated in Sweden by Epizootic Disease Act (1999: 657). 2WHO declared a pandemic on March 11th, 2020.

Regulation requires knowledge about what is to be regulated. It is a fundamental requirement. In the case of corona, this condition is missing. The coronavirus has so far shown unknown symptoms and disease progression, which counteracts knowledge concerning which measures are to be taken. The same applies in terms of infections. Knowledge about the risk of infection and the spread of the new virus is uncertain. Despite this, the government is obliged to do what it can to prevent the virus from spreading according to, for example, the Swedish Communicable Diseases Act (2004: 168). The Communicable Diseases Act opens for some intervening measures, such as decisions of isolation and closure of areas with a ban on leaving and entering that area. This is an example of legal support for societal measures. However, there is another side to legal regulation. It must be perceived as legitimate by those affected if it is to have the intended effect. Criminal law with its long tradition and internalized norms has population majority support and as such, is legitimate3. Rules of conduct in the form of restrictions and injunctions concerning corona do not have the same spontaneous support in the population. The law can be used to influence social norms in a specific direction, however that requires either severe sanctions and means of control or support and stimuli of various kinds. All legal regulation contains a consideration of legality and legitimacy, i.e., it must be predictable partly by being establishedstandardized- in law or the constitution, and partly by being accepted by the citizens. This consideration is added to the political system when it comes to the drafting of legislation and its content. The task of law is to make a corresponding consideration in the implementation of the law. It is an important task for courts and authorities to undertake in the individual case. The law always leaves some leeway for consideration between the letter of the law and its intended function4.

What are then the socio-legal challenges that corona faces?5 What is fundamentally new is that society has been challenged by a pandemic, by a virus that threatens humanity, which must therefore try to intervene in various ways to protect itself against the intruder. It is a new phenomenon that brings forth a plethora of different measures. The authorities must focus on tracking the different contexts in which the virus may appear and pose a risk of infection, from home, school, workplace, to sporting events, theater, cinema, public gatherings, transport, etc. Since these contexts belong to different policy areas and are regulated by different laws, the corona regulations are difficult to get hold of6. It can be seen as a patchwork quilt lacking normativity. It is not the politicians and lawyers who decide the agenda, but rather it is the enemy’s capricious behavior-the coronavirus and covid-19-or in other words: an assessment of the current epidemiological situation. Most of the regulations that are issued are limited in time and depend on the spread and intensity of the virus7. At the same time, individuals are expected to know which regulations apply where (in which context) and when8.

Impact strategy

Sweden has been criticized for having-at least by the outside world-a relatively liberal corona policy. Sweden has, to a large extent, relied on influencing people’s behavior through norm formation and not legislation. However, Sweden has partly been obliged to do so. Throughout our war-free history, we have never been forced to introduce in the Constitution the possibility of emergency laws9 in the same way that other countries have [4]. It is only now at a later stage of the pandemic that such measures have been introduced in Sweden. However, I will return to that later. Let us see first the characteristics of the strategy that has dominated. It consists of an effort to influence people’s norms and behavior to minimize the risk of infection. It is the Swedish Public Health Agency (FHM) with the support of the Swedish Communicable Diseases Act (2004: 168), who is responsible for coordinating infection control at the national level, as well as taking the initiative required to maintain effective infection control. FHM must monitor and further develop an infection control plan, as stated by law, as well as monitor and analyze the epidemiological situation nationally and internationally. During the corona pandemic, the chief epidemiologist and FHM’s director-general act as chief ideologues and army commanders with the task of raging a war against corona through engaging the 21 regions in working on infection control and healthcare. In each region, it is required to have an infectious disease specialist (Chapter 1, Section 9) who is responsible for ensuring that necessary infection control measures are taken within the region.

Footnote

3Its value lies in intervening against those who, for one reason or another, nevertheless commit crimes.

4Cf. what in sociology of law’s jargon has its origin in one the subject’s pioneers, the so-called the difference between law in books and law in action, see Pound, Roscoe (1910).

5This article is written in real time, i.e., it is written while the problem studied manifests itself. Therefore, I would like to reserve myself for leaving out socio-legal aspects concerning corona that in few years’ time may prove to be significant.

6These are very extensive that the so-called Restriction Proclamation (more on this below) proposes that an agency should be commissioned to keep a list of regulations that have been issued by administrative authorities or municipalities authorized under the law on special restrictions to prevent the spread of the disease covid-19, as well as the law on temporary infection control measures in venues serving food and drink.

7As an example, FHM has since December 18th, 2020 recommended municipalities and regions to close all activities that are not necessarily need to be open, such as swimming halls, libraries, county museums, and open preschools. It has been extended until February 21st, 2021.

8Cf. Nylén [9].

9This should be distinguished from the concept of state of emergency, which is one of very few cases where rights do not require the enactment of a new law but can choose to be used voluntarily by the highest political power. See the Constitution investigation’s report, SOU 2008: 61 Crisis preparedness in the Constitution-Review and international outlook. There is no possibility to declare a state of emergency or national emergency in Sweden.

Sweden, like other countries, has been able to find few countermeasures against the enemy-the virus. So far, there is a lack of antiviral drugs that can slow down the effect of the virus in the infected individual. According to the Communicable Diseases Act, the regions must offer vaccinations against infectious diseases to prevent the spread of these diseases in the population. Here, too, corona creates problems since vaccines must be developed, which takes time to get approved. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) makes thorough assessments of the efficacy and safety of vaccines. There are high standards of safety before the vaccines are approved, a process that usually takes several years. However, due to the impact of the corona pandemic on our health and society in general, large amounts of resources and money have been invested in vaccine development. The European Commission approves covid-19 vaccine for use in the EU based on the assessment of the European Medicines Agency (EMA)10. Once a vaccine has been approved, the regions are dependent on the pharmaceutical companies’ deliveries. Although this causes delays in many cases, the Swedish government expects that those who wish to be vaccinated will have the opportunity to do so during the summer of 2021.

Individual Rights vs Collective Interests

A Corona infection is highly personal. If it is to be combated, the measures required are to penetrate otherwise highly private spheres, those that are protected by constitutional freedoms and rights. Chapter 2 in the constitution contains provisions on protection against infringement that involve surveillance or systematic monitoring of the individual’s personal circumstances (Section 6), which prescribes that everyone is protected against invasions of their personal privacy if these occur without their consent and involve the surveillance or systematic monitoring of the individual’s personal circumstances. These are precisely the interventions that are required in the fight against corona11. Regarding the restrictions, it can be mentioned that such measures may only be executed to satisfy goals that are acceptable in a democratic society (Chapter 2, Section 20). The restrictions must also never go beyond what is necessary regarding the goals that prompt it, nor extend it so far that it constitutes a threat to freedom of speech, which is one of the foundations of a democracy. The freedom of assembly and right to protest are also protected. They may be restricted only for public order and safety reasons when it comes to meetings or demonstrations. It is also stated that these freedoms may be limited only with regards to the security of the realm or to combat an epidemic. Corona and covid-19 are comparable to an epidemic, which in its turn can be equivalent to a threat to the security of the Realm. This opens the possibility for the government to, by law, restrict the freedom of assembly and the right to demonstrate with reference to the progress of the coronavirus.

It is not only constitutional rights that need to be modified, but also that measures against covid-19 necessitate that citizens be subject to far-reaching restrictions in the private sphere. The political system is confronted with tasks that are not normally perceived to be political, such as communicating and influencing social norms12. Both the context and the content of norms make it difficult to maintain the ordinary requirements of legal regulation. The traditional attributes of legislation in the form of monitoring and sanctions appear to be difficult to implement. How far one can go in terms of sanctions is ultimately an issue of legitimacy. This is determined by the severity of the problem. The greater the danger associated with the spread of infection; the more intrusive sanctions can be introduced13. This means that political governance in relation to corona, to a large extent, relies on social norms with a reference to the individuals’ self-interest, i.e., to protect themselves from the infection.

Footnote

10Eight vaccines have been approved for early or limited use (end of March 2021). Four vaccines have been approved for full use and four vaccines have been abandoned following clinical trials. A total of 78 vaccines against covid-19 will undergo clinical trials in humans in the spring of 2021, of which 23 are in phase 3, the last phase before a full approval.

11It may be noted that the Constitution is addressed to the Parliament and the government and it prohibits them from introducing rules without special legal support to violate the freedoms and rights stated in the Constitution, Chapter 2. This means that laws and Ordinances that violate the Constitution can be annulled by court, but not that individuals can base their own legal claims on the provisions of the Constitution.

12This is something different than the fact that politics sometimes effects social norms, see Rothstein, 1998.

13It is easy to paint scenarios where the spread of infection appears so serious that very far-reaching restrictions in people’s everyday lives are gaining acceptance. An example of such dystopian reality can be found in the Netflix series (2020), The Barrier.

Society Reactions

In general

In Sweden, authorities occupy an independent position and thereby have a direct political function through a mandate to act (by delegation) issued by parliament and the government. When it comes to the formulation of policy concerning corona, the expert agency in the field of infection control, the relatively new FHM, has a central role14. It came into the limelight after having been among anonymous agencies. The strong position that FHM occupies in relation to the pandemic is partly due to the nature of it being a specialist agency in its area, and partly due to the generally strong status that medicine has in modern society, which means that the general political priorities take a back seat and lets «those who know», or claim to know, voice their expert opinion [5]. Accordingly, democracy has been replaced by meritocracy in Sweden when it comes to this issue [6]. This is not as clear in other countries15. Another interesting socio-legal phenomenon that follows in the footsteps of the management of the coronavirus is the normative implications of scientific conclusions that determine the normativity, i.e., the knowledge that science generates has direct normative significance and something that must be followed16. The virus composition, reaction, and spread patterns can be directly translated into norms on how we should behave to reduce the spread and stay away from the enemy-the coronavirus17. A particular problem in this context is that the Communicable Diseases Act requires decisions concerning communicable disease control measures to be based on science and proven experience and may not be more far-reaching than is justifiable regarding the danger to human health (Communicable Diseases Act, Chapter 1, Section 4). This becomes particularly problematic in a situation where the phenomenon to be regulated is new from both a medical and societal point of view, and that it additionally changes through constant mutations18. There is essentially no established science and proven experience to fall back on19. This contributes to the authorities’-FHM and others’-actions often appearing shaky and difficult to understand, which affects citizens’ acceptance of the advice, recommendations, and regulations that are communicated, and thus the legitimacy of the entire system20.

The regulatory staircase

From a regulatory perspective, the strategy of FHM can be seen as recommendations based on voluntary compliance. But the agency can, with the support of legal means, step up the steering in various ways. This can be done through different steps, a kind of regulatory staircase based on different degrees of normativity21:

i. Social norms, which are based on voluntary compliance,

even though this voluntariness may be compulsory in the

specific case.

ii. Recommendations, which are orally articulated.

iii. Recommendations, which are part of the government

decisions and/or the government regulations.

iv. General advice, which is part of the government

regulations.

v. Ordinances issued by the government on delegation by

Parliament.

vi. Laws, promulgated by the Parliament.

vii. The Swedish Constitution.

viii. The European Convention on Human Rights, as part of

Swedish law.

Footnote

14The Swedish Public Health Agency was established on January 1st, 2014 through a merger of the Swedish Institute for Infectious Disease Control in Solna and the National Institute of Public Health in Östersund. At the same time, most of the National Board of Health and Welfare’s work with environmental health, as well as reporting of environmental and public health was transferred to FHM. On July 1st, 2015, FHM took over the coordinated responsibility for the area of infection control, which was previously handled by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

15In e.g., Denmark and most other countries, the political system and the Prime Minister play a stronger role than in Sweden, see Julie Hassing Nielsen [7]. See also the handling of covid-19 in the spring of 2020 report submitted by the investigation group set up by the Folketing’s Committee on the Rules of Procedure regarding the handling of covid-19.

16Otherwise, the common notion is that norms as expectations have a sender and that norms are created in the interaction between people. It does, however what is more important are the standards based on expectations in medicine and technology. The norms are increasingly a consequence of expectations built into infrastructure of various kinds, of digital technology, etc. Cf. Lessig [8]: Code is law. See also Hydén [1].

17This does not mean that these knowledge-based actions and norms, are unambiguous and/or undisputed. As an example, one can point to the “battle” over whether face masks should be used or not. Here, perceptions change among the experts and the public is ambivalent, which has led to face masks being advocated and required e.g., during rush hour on public transport [9].

18It is typical for viruses to mutate all the time. So does the corona virus SARS-CoV-2. When viruses multiply, changes, i.e., mutations, occur in their genome. Viruses with mutations may have characteristics that differ from the virus strain previously spread among the population. There are currently several different variants of the coronavirus circulating in the world. There is a British, a South African, and a Brazilian variant. Some of these variants spread faster than previous virus strains. According to current data, the coronavirus vaccines currently in use also provide protection against these virus variants, but the vaccines may be less effective against certain mutations.

19The problems are the same when it comes to the environment and climate issues, where measures have been postponed. This is something that cannot be done when it comes to corona, where the problems are clearer, and one cannot wait until they become disastrous.

20This is evident in many countries through street demonstrations and protests. In Sweden, it has also been expressed in e.g., death threats against the officials who served as messengers for restrictions of various kinds.

21The terminology is that a law is decided on by the Parliament while an Ordinance is decided on by the government. For the sake of clarity, this should be separated from EU law, where a distinction is made between EU regulation and directives. A directive sets out the goals to be achieved by the member states, but it is up to them to decide how to proceed. EU regulation is a binding legal act that all EU countries must apply in their entirety. In the field of public health, the EU has limited competence - the Member States have the main responsibility. At the same time, the crisis affects EU cooperation, however this topic falls outside the scope of this article.

I have commented on social norms above. A recommendation is neither binding nor linked to a binding rule (unlike the general advice). However, a recommendation is based on all the knowledge that exists in a particular subject. The normative emanates from the cognitive, not from morals, values, or social norms22. The notion is that it is a good idea to follow a recommendation that comes from a governmental agency. From a regulatory point of view, it can be said that the regulation falls back on people’s self-interest in wanting to protect themselves. This means that the regulation strategy is based on voluntariness. There is a whole range of requirements for measures here. They are all examples of highly unusual interventions in the lives of citizens, which is why I choose to mention some of them below [10]. It can be seen in the perspective of the regulatory staircase as a relatively long and wide ledge before the stricter steps take over23.

The struggle escalates - norms become rules

The success of the voluntary strategy - after all - is based on the state and the authorities in Sweden being perceived to be ‘good’. The welfare state has contributed to this image24. From an international perspective, these institutions enjoy high legitimacy. Confidence in the Swedish political and administrative system is high [11]. However, voluntary governance can always be strengthened through legislation if necessary. It is not uncommon for legislation to be needed to boost compliance of otherwise voluntary rules. The Act (2021: 4) introduced at the beginning of 2021 concerning special restrictions to prevent the spread of covid-19 disease, the so-called pandemic law in Sweden, is one such example. Despite the special statutes of corona, the government and parliament had no possibility to intervene in the private sphere and in private commercial contexts. It rubbed people the wrong way that while only a maximum of 8 people could attend public gatherings such as football and ice hockey matches, a little over 3,000 people could go to Ullared (a shopping center) for shopping during the course of one day. The compliance with FHM’s recommendations and general advice risks diminishing over time, while the virus that causes covid-19 disease continues to pose a serious threat to the population. For this reason and at the turn of the year (2021) the Act (2021: 4) on special restrictions to prevent the spread of the disease covid-19, the so-called Pandemic law, passed as a framework law25. It opens for the government to issue Ordinances and for FHM to issue legally binding regulations. Since the Pandemic Law is a framework law, it does not in itself contain binding regulations for individual citizens, however it states in which issues and in which areas the government and FHM may promulgate regulations.

The Pandemic Law entered into force on January 10th, 2021, which lays the ground for measures to be taken against crowding or preventing the spread of infection in another way. The government or the agency appointed by the government may issue regulations on special restrictions regarding certain activities and places covered by the law. The Ordinance (2021: 8) on special restrictions to prevent the spread of the disease covid-19 (the restrictions Ordinance) is one such regulation. It came into force at the same time as the Pandemic Law. The Ordinance means that various types of infection control measures must be taken at public gatherings and public events, at gyms and sports facilities, swimming halls, places of commerce, as well as when using and leasing premises, areas and spaces for events and similar private gatherings. In addition, the government and the responsible administrative authorities have, both before the Pandemic Law came into force and after, taken many measures to limit the spread of covid-19 disease. Examples of such measures are that the government has banned the sale of alcohol after 20.00 until February 28th, 2021 (Ordinance (2020: 956)). This ban has since been extended gradually. The rules have been extended to apply to all types of businesses, i.e., regardless of whether alcohol is sold or not26. FHM also decides on further restrictions of how many people can stay in shops, malls, and gyms. The restrictions ordinance, like the Pandemic Law, has been issued so that the government can, if necessary, act quickly in a rapidly deteriorating infection situation. The need to close or ban activities must be based on an assessment of the current epidemiological situation. The Ordinance should be limited in time and valid for four weeks27. The Ordinance may only be issued if it is a necessary and has proportionate measure to prevent the spread of infection, and if other infection control measures are deemed insufficient, which means that in such a situation there are no alternative solutions that sufficiently prevent the spread of infection at the places in question.

Footnote

22This makes arguments for compliance more or less obvious.

23It is precisely the voluntary aspect of the regulations that makes them so detailed that they are practically more or less impossible to control. It is up to everyone to follow, for their own sake and for the sake of their fellow human beings.

24To demonstrate this, it can be pointed out that Sweden has had a relatively low profile in the field of human rights. Not that Sweden has been against human rights, but that human rights have not been fought for by the people in a struggle against power. Human rights have been provided by the state and authorities as a part of the welfare state. In Sweden, human rights have not been rights for the individual citizen but an obligation for the state and governmental agencies. Influence, not only from the EU, has contributed to change in, for example, education, where according to the Swedish Education Act, compulsory schooling is a right for each individual. The Convention on the Rights of the Child, which has become Swedish law, has also contributed to this, see Hydén 2006.

25See Hydén & Hydén (2019) [2] and Esping (1984) [12].

26The government has made decisions that allow the Swedish Public Health Agency to limit the opening hours for venues serving food and drink, such as restaurants, cafés, and bars. This can affect all businesses involved. FHM may introduce such rules nationally or for a specific geographical area, such as a county or a municipality. Initially, this will mean a national limitation of the opening hours to 20:30 for all venues serving food and drink. The amendments came into force on March 1st, 2021.

The Swedish government has announced a special so-called shutdown support28 which is designed as an enhanced adjustment support and will be managed by the Swedish Tax Agency. The shutdown support is targeted at companies that are unable to conduct their business because of closure decisions issued on the basis of the Pandemic Law or the Temporary Infection Control Measures Act concerning venues serving food and drink. The government has previously granted several different support measures29, such as short-term layoffs support since mid-March 2020, which has been extended to June 30th, 2021, as well as adjustment support from August 2020 to April 30th, 2021. A temporary payment respite is available to companies according to the law in place since February 5th, 2021. From August 2020 until April 2021, the state reimburses employers for higher sick pay costs than can be considered normal. The employer’s contribution was generally reduced in March-June 2020 and for young people (19-23 years) from January 1st, 2021. Rent support has also been paid between January-March 2021.

The government has been criticized for not acting more urgently and for being too passive in the fight against the coronavirus. One example is that the entire government, at the initiative of the opposition, been summoned for questioning before The Committee on the Constitution (KU) to answer the question of whether the government really ruled the Realm during the pandemic or whether it has passively delegated responsibility to FHM? In order to find an answer to that question, the KU began a long line of hearings regarding the Swedish corona strategy on March 25th, 202130.

Potential Regulations

The function of the Pandemic law as a framework law allows the government and authorities to, if necessary, be able to do what previously rested on a voluntary basis, legally coercive measures. To enable effective interventions concerning the spread of infection, an assessment is made in the Pandemic law concluding the necessity to produce a draft of an Ordinance on temporary closures and bans, which covers more than malls and department stores. The Ordinance means that several places of business may be kept closed to the public if they take place indoors. It can be argued that at a relatively late stage of the pandemic, Sweden is equipped to fight the enemy, the corona virus, with legal means. It can be noted that a general curfew – something that occurs in many countries in terms of lockdown-is not possible under Swedish law. The Swedish Constitution stops such restrictions on freedom of movement without the support of law and it is something that by necessity takes time. It can be added that there are also other government agencies that have oversight in accordance with their specialized legislation. Thus, the Swedish National Agency for Education is considering ways to use its power according to the Education Act to contribute in reducing the spread of infection in schools (The Act (2020: 148) on the temporary closure of school activities). Another source of infection is the workplace. In this area, the Swedish Work Environment Agency, and the Work Environment Inspectorate act to ensure that the risk of infection with the virus is generally considered in work environments. Decisions on fines have also been made here to enforce rectification which could not be achieved voluntarily.

Trade-offs between law and context

If we compile what has been said above and try to sew together the normative fragments that make up the pandemic’s regulatory patchwork quilt, we can capture the following.

The Swedish regulation has the following direction of movement:

i. From soft to hard regulation.

ii. From self-regulation to legal regulation.

iii. From individual to collective orientation.

iv. From norm to rules (from informal to formal norms).

v. From politics to law.

vi. From dependence on legitimacy to focus on legality.

Thus, the regulation transforms over time from influence through and by social norms with the support of recommendations and general advice to the use of legal rules, namely rules that have constitutional support and are issued by the Swedish Parliament and the government after delegation, as well as by agency after delegation from the government. The regulation moves over a threshold from informal to formal norms. It moves from the influence of social norms through recommendations to legal rules as clearly stipulate above. Legal rules can contain both soft law and hard law, i.e., more or less intrusive measures against citizens (Woodlock-Hydén 2020).

Footnote

27The Ordinance has been extended until the end of the year (2021).

28This must be approved by the European Commission.

29The government has been criticized for not paying financial support. The hospitality industry has been hit the hardest.

28sup> representatives of Swedish city centers, as well as various industry organizations, have voiced criticism toward the government.

30Hearings of ministers will take place in April 2021. The review includes a number of reports that have been received. The committee also conducts its own, broader review on eight points. The review takes place to some extent in parallel with the review that the Corona Commission is working on. The Commission shall submit the final report on February 28th, 2022.

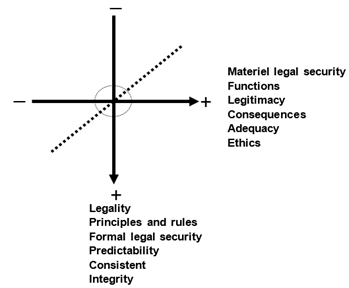

Form an effective impact point of view, it is conceivable that the stricter variant of legal rules to which sanctions may be linked would be more effective than the softer measures of influence linked to social norms. However, it is not really that simple. In both cases, the regulation is dependent on the acceptance of the persons in question. Legality presupposes legitimacy to function in terms of regulation. This applies to all regulation, which is particularly evident when it comes to the fight against corona, given that this regulation penetrates far into people’s private and everyday lives. Legality means that an action takes place in accordance with, or with the support of, legal regulation. That something is legitimate means that it is considered rightful or justified, meaning that people accept it in a normative sense31. Legality and legitimacy can in relation to the earlier mentioned regulatory staircase be schematically described as follows (Figure 1):

Figure 1: The relationship between legality and legitimacy.

Essentially, we can consider the legality requirements on an increasing scale the higher we go on the regulatory ladder, while the corresponding element of legitimacy increases the lower we get at the regulatory level. Another conclusion based on this reasoning is that all regulation, as well as all decision-making, is about achieving a balance between these two dimensions. Essentially, these are tradeoffs between law and context. Underlining law requires focus on legality while emphasizing context focuses on legitimacy. Influence through social norms can be as effective as laws and Ordinances since social norms can be associated with high legitimacy, while legal rules can be without effect if they lack legitimacy and this regardless of whether all the legality requirements are met. It can also be seen as a balance between formal and material legal security, i.e., a balance between transparent procedures and substantial content. See the following32:

The trade-offs between legality and legitimacy is represented by the dotted line in the (Figure 2). If one is to try to identify what characterizes one or the other, one can say that legality is about following rules, while legitimacy is about expediency, meaning that the important thing is to fulfill the purpose behind the regulation33. The higher the degree of legality, the lower the degree of legitimacy and vice versa34. If legitimacy is overemphasized, it is at the expense of legality. The optimal balance is in the bull’s eye, i.e., in the middle of the cross. This point constitutes an optimal compromise between the two competing requirements of legal regulation and decisionmaking, where one requirement, legality, can no longer be met at the expense of the other requirement, legitimacy. This problem is applicable to all legal regulation and decision-making; however, it is particularly relevant concerning the topic discussed in this article-corona. Let us take a closer look at this issue by following the regulatory ladder introduced above.

Legitimacy

Social norms constitute the most prominent position in terms of legitimacy. The more people who embrace the social norms, the higher the degree of acceptance. Thus, we can assume a high degree of legitimacy on a collective level. The social norms that FHM exhorts when it comes to corona can be seen to have a high degree of legitimacy. Indeed, these are partly new social norms, however regularly washing our hands, keeping our distance from each other affecting our way of greeting each other, as well as staying home when feeling sick, are all examples of social norms that are not very troublesome for individuals and therefore can be assumed to enjoy legitimacy. In this context, people talk about «the new normal». However, it can be something negative when it comes to not spending time with each other or going on (holiday) trips for risk of infection. For some, this means some great sacrifices, while for others not a major problem35. It can be assumed that the legitimacy is lower in these cases, especially if we consider the consequences over time.

Footnote

31For an in-depth discussion of the concept of legitimacy, reference can be made to Noyon et al (2021) [13].

32See further in Hydén et al. 2003 [14].

33This is something else and should not be confused with the teleological style of legal interpretation developed by the

Uppsala professor in Procedural law, Per Olof Ekelöf. This method is based on aspects of legality, while legitimacy is

about how the purpose of a certain rule is to be fulfilled. In the latter case, expediency governs the application of a rule.

34The reason why the dotted line does not go from the upper left corner to the lower right corner is because it lacks empirical validity. This would presuppose that legality and legitimacy are interconnected so that a low value of legality would be linked to a low value of legitimacy and a correspondingly high value of legality would be followed by a high legitimacy value, which is something that lacks validity.

The recommendations that FHM communicates at press conferences and other occasions, are largely about imprinting the social norms we have mentioned. To further emphasize the importance of these recommendations, these have, as we have seen above, been included in government regulations36. The same can be said regarding the general advice issued by FHM. General advice represents what is often called soft law. You decide how you want to fulfill the general advice. It is thus the expediency that determines the correct application, not the actual compliance as in relation to the legality requirements. For example, general advice on covid-19 has been drawn up by FHM.

Ordinances can generally be said to enjoy a lower degree of legitimacy simply for the reason that they are less well known in content. Indeed, one of the most important functions of the Ordinances is to operationalize the provisions of a law, but it is the law adopted by the parliament that appears to be the strongest in terms of legitimacy. However, when it comes to corona’s Ordinances and through these delegated regulations by primarily FHM but also the county administrative boards, to which legitimacy is attached. This can certainly be explained by the fact that the legally binding regulations in Ordinances and governmental regulations have their background in the social norms spread by the authorities. In that sense, the law has grown from the bottom up and it rests on expert knowledge. Sometimes a kind of tug-of-war arises between politics and expertise, between democracy and meritocracy.

An example is the controversial issue of the need to wear a face mask, something that is common in most other countries37. While FHM has persisted in the view that the scientific support for the use of face masks in society to curb the spread of covid-19 is weak, unlike other measures such as keeping a distance, voices have been raised in the political debate (see e.g., Motion 2020/21: 1139) for requirements of face masks to be introduced in Sweden as well, not least because other countries have such requirements. The issue of face masks is pedagogic as a symbolic issue insofar as it is clearly visible. Johansson [9] use the term blind trust to illustrate the phenomenon. The pressure on FHM has therefore increased and it had to finally budge, but only partially. In January 2021, requirements for face masks were introduced in public transport for people born in 2004 and earlier38. Non-holiday workdays between 7-9 and 16-18, there is a requirement to use a face mask when traveling with public transport where seat bookings are not offered.

The Constitution and its provisions in Chapter 2 on freedoms and rights can be said to enjoy a high degree of legitimacy, something that weighs heavily in relation to legality. This also applies to the European Convention, although its legitimacy rests more on the symbolic than the operational level. Freedom of expression, assembly, and freedom of movement are fundamental rights enshrined in the European Convention39. The emergency measures taken by European countries to slow down the spread of the coronavirus have had several side effects, including a restriction on precisely these fundamental rights40. Critics have even claimed that in some countries the situation has been politically exploited to enforce dubious laws that have nothing to do with the fight against covid-19. These are examples of actions that are legal but have limited legitimacy.

Examples of other external effects of corona regulation can be argued to be economic consequences that have been extensive, as well as mental health problems. The former is not a legitimate argument in connection with the regulation but is certainly there as implied considerations41. In any case, these negative external considerations entail financial support measures from the political system in the way expressed above. Mental health problems are something that has been increasing during corona42. Here, too, support measures have been taken.

Footnote

35Here, a possible class-differentiating aspect comes to mind, which is something that has been claimed to be a

consequence of the corona pandemic, namely the widening class gaps.

36See, for example, the Public Health Agency’s regulations and general advice on everyone’s responsibility to prevent

infection by covid-19 (HSLF-FS 2020: 12).

37Another example of such measures is that the government has banned the selling of alcohol after 20.00 until February

28th, 2021. This prohibition has since been extended gradually.

38HSLF-FS 2020:92

39The European Parliament resolution of 13 November 2020 on the impact of COVID-19 measures on democracy, the

rule of law, and fundamental rights.

40The Dutch government decided on a national night curfew in an attempt to curb the spread of the coronavirus. It would

be the first national curfew in the country since World War II. The decision was appealed. After the court’s decision, it

initially looked like the night curfew would come to an end. However, following an appeal, the court of appeal concluded

that the government had not clearly clarified why extensive repression and corona restrictions were necessary to combat

the virus and therefore demanded that the repression cease. However, the Court of Appeal has later chosen to follow the

government’s lead- after revelations about exaggerations and false information about the pandemic and the spread of

infection - and decided that a curfew is still necessary and legitimate to limit the alleged spread of infection.

41The restrictions on people’s freedom and the economic consequences have led to demonstrations and riots in many countries. This applies to e.g., countries such as Denmark, Spain, and Italy.

Legality

Regarding the Constitution, it has no direct legal effect on individuals. In contrasts, the European Convention can be invoked by individuals before the European Court of Human Rights. The problem here is that it is a relatively complicated and a costly process for the individual. The Constitution is mainly intended as a barrier for the parliament and the government when it comes to e.g., freedoms and rights. Individuals can claim that a certain law is contrary to the Constitution and therefore invalid. Curfews have been a relatively common measure to counter the spread of coronavirus in many countries. The fact that this was not implemented in Sweden is because the Constitution does not give the government the opportunity to declare a state of emergency. This is an important explanation to the fact that Swedish have not experienced a shutdown of society as in other countries, or that the Swedish government has not announced a curfew, which is simply because there is no legal basis for it. There is also a ban on restricting citizens’ right to leave their place of residence, as well as cordoning off larger areas such as border zones and parts of the archipelago, or a city. However, with the support of the law, individuals who have been infected or have been exposed to infection can be quarantined without the opportunity to leave or receive visits. This has been utilized through the so-called Pandemic law, which gives the government the opportunity to make decisions on this type of restriction. The use of this government’s opportunity for restrictions on the mobility of individuals is, according to the law, dependent on the risk of infection. It can be expressed as if the legality is directly dependent on the legitimacy, where the purpose here is protection against the risk of infection.

The Ordinances issued concerning corona meet the pro forma legality requirements to the extent that these regulations have been added to the legal order and remain in the field of legislative law. But by being added under time pressure with limited investigation and consultation time, legality can be questioned on various points43. It is easy to go wrong when the content of a rule is complicated. An example of a breach of legality is a case from the social services that concerns the protection of individuals’ lives, personal safety or health in activities that concern the elderly. The government or the agency appointed by the government, according to chapter 16, section 10, first paragraph 2 of the Social Services Act, may issue such regulations. The Ordinance (2020: 163) on the temporary ban on visits to housing for the elderly to prevent the spread of covid-19 disease was issued based on this provision. There is no corresponding authorization for municipalities. With this in mind, the Administrative Court in Sweden has found that a visitation bans on nursing homes decided on by a municipality constitutes an unauthorized interference in the right to private and family life. Thus, the Social Welfare Board’s decision contest the law and it will be repealed with the support of chapter 8 section 4p of the Local Government Act.

General advice and recommendations such as government regulations have otherwise been added to the legal order and thus meet the legality requirements. But if we legally look at the requirements for predictability and consistency, there is much more to be desired. I have spoken above using terms such as patchwork quilt and difficulty to identify different laws and Ordinances. Legality presupposes that citizens can perceive and adopt relevant norms. One can add some additional factors that affect formal legal security. The provisions that are introduced take place at such a pace that they have difficulty melting into people’s consciousness. They may be formally and materially acceptable, but uncertain where and when they apply.

It is easy to get lost in the regulatory jungle created by the coronavirus. This applies not only in Sweden but in most other countries. Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg has violated the country’s corona restrictions, which led to the Norwegian police investigating the Prime Minister’s actions. It was when Erna Solberg was to celebrate her 60th birthday with the family that a total of 13 people visited a restaurant together. Erna Solberg herself was not present at the restaurant, however on a later occasion she, in the company of 13 people, is said to have had dinner in an apartment. The limit for how many people can gather at private events was at the time ten, according to the Norwegian infection control rules. The Prime Minister later apologized for violating the restrictions and emphasized that she was not aware that the party had broken the rules. It is precisely this, the difficulties of keeping track of which rules apply, that is a fundamental precondition for the preservation of the legality principle [16].

Footnote

42Covid-19 primarily affects physical health, but the disease and pandemic can also have consequences for our mental health. This applies not least to the restrictions that have been necessary in order to reduce the spread of infection, which means that the physical contact between people is limited. A body of literature has been compiled on how the pandemic has affected mental health so far. The literature review published in August 2020 by FHM does not contain any Swedish study, however it provides a snapshot of research in the field during the first months of the pandemic. The studies have been conducted in countries in Europe, and in the USA, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. These countries can be seen to have had stricter restrictions than Sweden.

43It is beyond the theme and scope of this article to go into these aspects. For a review of Sweden from a legal point of view, see Wenander [15] and for an in-depth analysis of the (i) legality of Norway’s actions with regard to legal measures taken during the corona pandemic, see Graver, (2020). With regard to Denmark, see about the handling of covid-19 in the spring of 2020 in Report submitted by the investigation group set up by the Folketing’s Committee on the Rules of Procedure regarding the handling of covid-19.

The Balance between Legitimacy and Legality

With that said, we have reached the initial steps of the regulatory staircase-general recommendations and social norms. These governmental regulations may also be subject to judicial review, even though they are not formally legally binding44. As an example, reference can be made to cases where a court considered a recommendation from an agency to be binding. However, the problem can be seen as minor when it comes to corona, given that these forms of influence-social norms and general recommendations-are close to the general view held by citizens on a particular issue. Legality and legitimacy naturally converge in these cases, which is not a guarantee that the norms are complied with. There are always individuals who for one reason or another deviate from the current norms45.

Figure 2: Trade-offs between legality and legitimacy.

As a general conclusion, and in the light of the reasoning given and with reference to (Figure 2) above, it can be argued that legal regulation is most effective when legality and legitimacy go hand in hand. However, where these meeting points are found in practice varies with the nature of the problem46. An example where legality and legitimacy flow together is self-regulation. This concept is most often associated with the strategy of allowing the market to regulate a certain phenomenon, e.g., environment, consumer considerations, etc. In cases of self-regulation, it can be argued that legitimacy has reached its extreme as a form of regulation and thus erased the need for legality; self-interest and public interest merge and become one. In the case of corona, self-regulation is about the logic that characterizes the coronavirus’ life cycle. Since the virus has established itself in the human organism through jumping across species and made it its host, it has a vested interest to live in symbiosis with humans. It is therefore assumed from a medical point of view that the aggressiveness and danger of the coronavirus to humans decreases in the long run, to level out to be one of several viruses that humans have to live with and be treated against47 [19,20].

Swedish Laws and Regulations

1. Epizootilag (1999:657). (Epizootic Disease Act)

2. European Parliament resolution of 13 November 2020 on the impact of covid-19 actions on democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/ document/TA-9-2020-0307_EN.html). (European Parliament resolution of 13 November 2020 on the impact of COVID-19 measures on democracy, the rule of law, and fundamental rights, 2020/2790 (RSP))

3. Ordinance (2020: 163) on a temporary ban on visits to special housing for the elderly to prevent the spread of the disease covid-19 (Ordinance (2020: 163) on a temporary ban on visits to special housing for the elderly to prevent the spread of covid-19 disease)

4. Ordinance (2020: 956) on a temporary ban on the serving of alcohol (Ordinance (2020: 956) on a temporary ban on the serving of alcohol).

5. Ordinance, (2021: 8), on specific restrictions to prevent the spread of covid-19 disease (Ordinance (2021: 8) on specific restrictions to prevent the spread of covid-19 disease)

6. Proposal for an ordinance amending the ordinance (2021: 8) on special restrictions to prevent the spread of covid-19 disease. (Proposal for amending the Ordinance (2021: 8) on special restrictions to prevent the spread of covid-19 disease).

7. HSLF-FS 2020: 12, The Swedish Public Health Agency’s regulations and general advice on everyone’s responsibility to prevent infection by covid-19 m.m. (HSLF-FS 2020: 12, The Swedish Public Health Agency’s regulations and general advice on everyone’s responsibility to prevent infection by covid-19 etc.)

8. HSLF-FS 2020: 78, FHM’s regulations and general advice on a temporary ban on visits to special forms of housing for the elderly in order to prevent the spread of covid-19 disease. (HSLF-FS.

Footnote

44This is particularly common in the tax area, see Påhlsson [17]. See also Kleineman [18].

45Cf. here what has previously been said about the role of criminal law in terms of regulation.

46This article merely claims to provide evidence for such an assessment in this specific case by presenting relevant considerations.

47Here, vaccines play an important role in achieving balance, in a sort of a Cold War metaphor.

References

- Hydén H (2022) Sociology of law as the science of norms. Routledge Publishers, UK, pp. 1-368.

- Hydén T (2019) Legal rules: An introduction to law. (8th edn), Studentlitteratur, USA.

- Teubner G (1987) Juridification of social spheres: A comparative analysis in the areas of labor, corporate, antitrust, and social welfare law. De Gruyter Publisher, Germany, pp. 1-446.

- Nergelius J (2018) Comparative state law. (9th edn), Sweden.

- Jasanoff S, Hilgartner S, Hurlbut BJ, Özgöde O, Rayzberg M (2021) Comparative covid response: Crisis, knowledge, politics interim report. USA, pp. 1-121.

- Bell D (2015) The China model: Political meritocracy and the limits of democracy. Princeton University Press, USA, pp. 1-336.

- Hassing NJ (2021) Journal of Political Science 2.

- Lessig L (2006) And other laws of cyberspace, Version 2.0. Basic Books, USA, pp. 1-432.

- Johansson B, Sohlberg J, Esaiasson P, Ghersetti M (2021) Why swedes don't wear face masks during the pandemic: A consequence of blindly trusting the government. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research 4(2): 335-358.

- Nelken D (2021) Global social indicators, comparison, and commensuration: A case study of COVID rankings. Global Community: Year book of International Law and Jurisprudence 17(2): 215-234.

- Esaiasson P, Sohlberg J, Ghersetti M, Johansson B (2021) How the coronavirus crisis affects citizen trust in institutions and in unknown others: Evidence from 'the Swedish experiment’. European Journal of Political Research 60(3): 748-760.

- Esping H (1994) Framework laws in administrative policy. 1st (edn), Sweden.

- Noyon L, Keijser JW, Crijns JH (2021) Legitimacy and public opinion: A five-step model. International Journal of Law in Context 16(4): 1-13.

- Hydén H, Karsten Å, Annika S (2003) Stressing judicial decisions - A sociology of law perspective. I stressing Legal Decisions, IVR 21st World Congress Lund, Polpress, USA.

- Wenander H (2021) Sweden: Non-binding rules against the pandemic-formalism, pragmatism and some legal realism. Eur J Risk Regul 12(1): 127-142.

- Nylén N (2021) Orders and compliance? A matter of effective crisis communication. Journal of Political Science 2.

- Påhlsson R (2006) The Swedish tax agency's control signals-A new flower in the rule discount. Tax News, pp. 401-418.

- Kleineman J (2013) Legal dogmatic method. In: Korling F, Zamboni M (Eds.), Legal Methodology. Studentlitteratur Publishing Company, Sweden, pp. 21-45.

- Graver HP (2020) Pandemic and state of emergency: What covid-19 says about the Norwegian rule of law. Dreyer's publishing house, Norway.

- Neiman M (1998) Just institutions matter: The moral and political logic of the universal welfare state. American Political Science Association 94(3): 729.

© 2022 Håkan Hydén. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)