- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

Assessment and Characteristic of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) Success Rate in Urolithiasis: Report in Kariadi General Hospital Semarang Indonesia

Eriawan Agung Nugroho1*, Antonio Paulus Aditya Nugroho2 and Leonardo Cahyo Nugroho2

1Division of Urology, Medical Faculty Diponegoro University/Dr. Kariadi General Hospital, Semarang, Indonesia

2Resident of General Surgery Department, Medical Faculty Diponegoro University/Dr. Kariadi General Hospital, Semarang, Indonesia

*Corresponding author:Eriawan Agung Nugroho, Division of Urology, Medical Faculty Diponegoro University/Dr. Kariadi General Hospital, Semarang, Indonesia

Submission: June 11, 2019; Published: August 09, 2019

.jpg)

ISSN : 2688-836XVolume1 Issue4

Abstract

Introduction: Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) is one of the main choices in non-invasive therapy in urolithiasis. The success of ESWL therapy can be predicted from internal stone factors (size, location, number) and on the anatomy and abnormalities of the congenital urinary tract. Researchers wanted to know the assessment and characteristic of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) success rate in urolithiasis as a consideration for clinicians for urinary tract stones management.

Methods: This study used a retrospective descriptive design. Secondary data were taken from the medical records of urinary tract patients who received ESWL therapy at dr. Kariadi General Hospital, Semarang, Indonesia during the period 2012-2017. The variables seen were sex, age, size, session time, shock energy, unilateral/bilateral, opacity and anatomy location. After the data collected, we analyzed the prevalence of each variables with SPSS 21.0 for Windows.

Results: The incidence of urinary tract stones in male was 1.8 times higher than women.

a) Most incidences were in 41-60 years-old group (64.7%).

b) Average stone size in men 12.34 + 2.96 mm while in women 12.47 + 3.06 mm.

c) ESWL sessions averaged 1.8 sessions / patient.

d) The use of shock waves between 615 - 5000 shock counter and energy 344 - 1500 Joule.

e) Unilateral stones were found to be highest in both sexes (64.3% in male and 64.7% in female).

f) The most sites of stone was middle calyx (36.9%).

g) Radiopaque stones were found to be highest in both sexes (88.2%).

h) The lowest success rate of ESWL on the stone located on the lower calyx (73.8%).

Conclusion: ESWL is safe and effective for urolithiasis but before choose on ESWL procedure it is important to consider the location, size and density of the stone that will influence the success rate of the therapy.

Keywords: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL); Urolithiasis; Success rate

Introduction

Urinary stones are the third most urological problem after urinary tract infections and pathological conditions in the prostate [1]. Data from five European countries, Japan, and the United States showed that the incidence and prevalence of stone disease has increased over time worldwide. It was mentioned that the increase was associated with increased detection of asymptomatic urinary tract stones through the use of radiographic imaging, mainly from computed tomography [2]. Stone incidence varies with age with low incidence rates in childhood and elderly and peaks between the 4th decade and the 6th decade of life [1-3].

There are several studies that found that urinary tract stones are more common in working adults and then decline in older individuals, this may be related to diet, occupation, and lifestyle changes [3]. Overall, men always predominate in the prevalence, mentioned men two to three times more affected than women [2,3]. Other literature also mentions men’s 1.5-2.5 times more than women worldwide [4].

Methods

This study used a retrospective descriptive design. Secondary data were taken from the medical records of urinary tract patients who received ESWL therapy at dr. Kariadi Hospital, Semarang, Indonesia during the period 2012-2017 with EDAP Sonolith i-sys. Patients are excluded when there was a congenital anomally of the urinary tract. The variables seen were gender, age, location of stone, stone size, urinary side involvement, ESWL session count, total shock and given energy, and opacity of the stones. We also divide patients by <20 years-old, 21-40 years-old, 41-60 years-old, and >60 years-old categories based on the literature that mentions the incidence of urinary tract stones peaks between the 4th and 6th decades. After the data collected, we analyzed the prevalence of each variables with SPSS 21.0 for Windows.

Results

From 1927 patients enrolled in the study, 1241 male patients (64.4%) and 686 female patients (35.6%) with a ratio of 1.8: 1 were found. Most age categories were 41-60 years-old as 1246 patients (64.7%), followed by groups of 21-40 years-old as many as 333 patients (17.3%). The least was in the <20 years-old group of 17 patients (0.9%) (Table 1).

Table 1:Patients distribution based on age categories and gender.

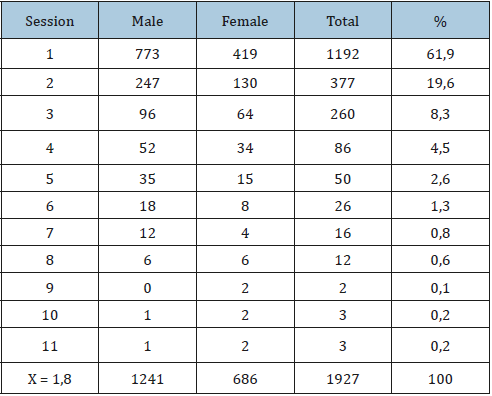

Table 2:Patients distribution based on sessions and gender.

The number of ESWL therapy sessions varied between groups of men and women ranging from 1 session to 11 sessions with an average of 1.8 sessions / patients. In this research we get the use of shock wave between 615 - 5000 shock counter and energy between 344 - 1500 Joule (Table 2).

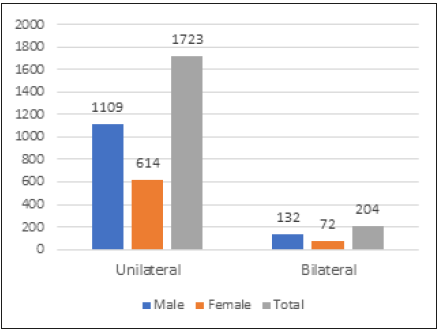

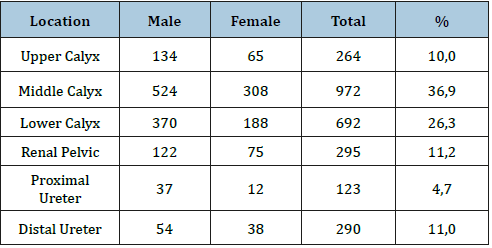

Based on urinary tract involvement, both male and female groups were dominated by unilateral stones with a percentage of 64.3% in male and 64.7% in female, respectively. Average stone size in the male group was 12.34 + 2.96 mm while in the female group was 12.47 + 3.06 mm (Figure 1). From this study found the most stone sites are middle calyx (36.9%), followed by lower calyx (26.3%) and renal pelvis (11.2%). The location of the fewest stones is the proximal ureter (4.7%) (Table 3).

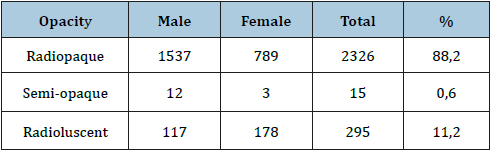

From the data obtained, both in the male and female group found the most stone types are radiopaque (88.2%), followed by radioluscent (11.2%) and semi-opaque (0.6%) (Table 4).

Figure 1:Patients distribution based on stone duplexity.

Table 3:Stone location distribution based on gender.

Table 4:Stone opacity based on gender.

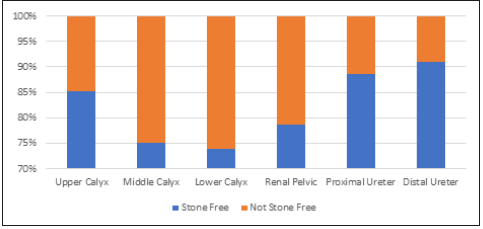

Figure 2:Success rate of ESWL based on stone location.

Based on the calculation, the lowest success rate of ESWL was on the stone located in the lower calyx (73.8%), followed by the middle calyx (75%) and the renal pelvic (78.6%). While the highest success rate on stones located in the distal ureter (91%), followed by proximal ureter (88.6%) and upper calyx (85.2%) (Figure 2).

Discussion

Management of urinary tract stones with ESWL is safe, effective and minimally invasive. Once we find the location of the stone, ESWL machines will send thousands of shock waves in the area causing the decomposition of the stone to become a bunch. After therapy, the stone fragments will come out through the urine [6].

Previous clinical and epidemiological studies have shown that the indication of ESWL treatment depends on several factors, including size, localization, consistency and other histologic characteristics of the stone [9]. This study found the incidence of urinary tract stones in men greater than women (Table 2). This finding is in accordance with the literature and some previous studies [1-4].

The most urinary tract stones incidence happened in age categories 41-60 years-old (Table 1). This finding is also in accordance with the literature that the highest incidence of urinary tract stones between the 4th decade and the 6th decade (2). There have been several studies that found that urinary tract stones are more common in working adults and then decline in older individuals. Increased incidence in middle age group may be associated with diet, occupation, and lifestyle changes [4].

The number of ESWL therapy sessions varied between male and female groups with an average of 1.8 sessions / patients (Table 2). This is because some patients have more than one stones for unilateral side or there are stones on both sides / bilateral. In some cases, patients still want to keep ESWL even though it has been explained that with multiple stone sites will require more therapy sessions and longer time, although other modalities had been offered.

Based on the involvement of the urinary tract, both in the male and female groups dominated by unilateral stones with the most locations are the middle calyx (Figure 1, Table 3). But other studies mentioned the most location of the stone is the lower calyx [10]. The relationship between location and stone formation remains unclear but it is explained that narrowing of the urinary tract increases the risk of sedimentation of urine [2].

The average stone size in the male group is 12.34 + 2.96 mm whereas in the female group is 12.47 + 3.06 mm, this stone size fits perfectly with the guideline stating that ESWL is effective for stones of size 10 - 20 mm [10,11].

From the data obtained, both in the male and female group found the most stone types are radiopaque (Table 4), this is in accordance with the literature and previous research [1-4,10]. Based on the calculation, the lowest success rate of ESWL is on the stone located in the lower calyx (Figure 2). This is affected by the anatomy of the infundibulo-pelvic angle, the infundibulum length, and the width of the infundibulum. Steep infundibular-pelvic angle, long and narrow infundibulum can impair successful stone treatment by ESWL [11,12].

The results of this study contradict previous studies which show that renal stone localization has better therapeutic ESWL results than the lower portion, such as ureter [6].

Conclusion

ESWL is safe and effective for urinary tract stones but before deciding on ESWL it is important to consider the location, size and density of the stone that will influence the success of the therapy.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- Stoller ML. Urinary stone disease. In: McAninch JW, Lue TF. Smith & Tanagho’s General Urology.

- Pearle MS, Antonelli JA, Lotan Y (2016) Urinary Lithiasis: Etiology, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA (Eds). Campbell-Walsh Urology (11th edn), Elsevier Inc., Philadelphia, USA, pp. 1171-1199.

- Sorokin I, Mamoulakis C, Miyazawa K, Rodgers A, Talati J, Lotan Y (2017) Epidemiology of stone disease across the world. World J Urol 35: 1301-1320.

- Walker V, Stansbridge EM, Griffin DG (2013) Demography and biochemistry of 2800 patients from a renal stone clinic. Ann Clin Biochem 50: 127-139.

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Riset Kesehatan Dasar (2013) Jakarta: Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan, Indonesia, pp. 94-96.

- Junuzovic D, Prstojevic JK, Hasanbegovic M, Lepara Z (2014) Evaluation of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL): Efficacy in Treatment of Urinary System Stones. Acta Inform Med 22(5): 309-314.

- Maltaga BR, Krambeck AE, Lingeman JE (2016) Surgical Management of Upper Urinary Tract Calculi. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA (Ed). Campbell-Walsh Urology (11th edn), Elsevier Inc, Philadelphia, USA, pp. 1265-1290.

- Al-Ansari A, As-Sadiq K, Al-Said S, Younis N, Jaleel OA, et al. (2006) Prognostic factors of success of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) in the treatment of renal stones. Int Urol Nephrol 38(1): 63-67.

- Pu YR, Manousakas I, Liang SM, Chang CC (2013) Design of the dual stone locating system on an extracorporeal shock wave lithotriptor. Sensors (Basel) 13(1): 1319-1328.

- Noviandrini E, Birowo P, Rasyid N (2015) Urinary stone characteristics of patients treated with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital Jakarta, 2008-2014: a gender analysis. Medical Journal of Indonesia 24(4): 234-238.

- http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-Urolithiasis-2016-1.pdf

- Gupta NP, Singh DV, Hemal AK, Mandal S (2000) Infundibulopelvic anatomy and clearance of inferior caliceal calculi with shock wave lithotripsy. J Urol 163: 24-27.

© 2019 Eriawan Agung Nugroho. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)