- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Practices in Medical Study

An Exploration of Illness Perceptions of Bulimia Nervosa Among Women Who Recovered from the Disorder

Pamela Portelli* and Maria Darmanin

Department of Psychology, University of Malta, Malta

*Corresponding author: Pamela Portelli, Department of Psychology, Faculty for Social Wellbeing, University of Malta, Msida, MSD 2080, Malta

Submission: December 12, 2022 Published: January 06, 2023

NPMSVolume1 Issue2

Abstract

This study investigated illness perceptions of Bulimia Nervosa as held by women who recovered from the disorder. It investigated how local social and cultural factors affect an individual’s experience of bulimia, and the impact of bulimia on women’s identity before and after recovery. In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with eight participants. Data was analysed using Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Leventhal’s Self-Regulatory Model of Illness Perceptions was a lens through which data was interpreted. Three global themes emerged namely perceptions of the disorder, sociocultural factors and identity construction. Findings reveal that bulimia has wide-ranging biopsychosocial implications. It is characterized by shame and secrecy and equated to an addictive disorder. The disorder was described as being internalized to the extent of consuming the individual, blurring one’s self-concept. Findings highlight how identity changes during the course of bulimia and recovery from it. Participants commented on experiencing mismanagement of symptoms and lack of awareness of the disorder among healthcare professionals. They explain how sociocultural factors such as prevalent food practices and public perceptions of bulimia might impact a person who is affected by this disorder. This has implications for help-seeking behavior. Recommendations for clinical practice, policymakers, and future research are outlined.

Keywords:Bulimia nervosa; Reflexive thematic analysis; Illness perceptions; Sociocultural factors; Identity

Introduction

Bulimia Nervosa is a disorder that poses significant biological, psychological and social risks. Research has documented the powerful role sociocultural influences have on the development and maintenance of Eating Disorders (ED) as well as subjective beliefs individuals may have about their illness [1]. Illness perceptions or the individual’s appraisal and understanding of their illness will influence the way ED clients adapt to and manage their condition [2]. Influential theories on eating disorders such as the Tripartite Influence Model tend to implicate the self as part of the eating disorder pathology. This stems from a history that has intimately connected eating disorders to the self and identity [3]. Bulimics use more constructs related to the body and body appearance to construe their sense of self as opposed to women without bulimia who focus more on personal qualities such as value systems when describing themselves [4]. This resonates with the fact that ED are ego-syntonic, so overcoming them may be seen to conflict with personal values [5]. As mentioned above, biological factors may predispose the individual to the development of an eating disorder. The role of the global chronic disease epidemic may have a major impact on Bulimia Nervosa in women. The effects of various factors on the brain that regulate appetite regulation may induce various diseases that are connected to the apelinergic system [6]. Multilayered and complex disease is possibly connected to obesity and neurodegenerative diseases [7]. The consumption of xenobiotics may cause brain disorders and appetite dysregulation in these women [8,9]. Literature associates ED with social identity. Some women regard their bulimic identity as being aligned with distinct selfhood [10]. Participants in a study by Eli’s framed their disorder as ‘abnormal’, carrying with it an element of social stigma and shame. This ‘abnormality’ was described as going beyond pathology since through proclaiming a bulimic identity, these females positioned themselves as non-conforming subjects who acted against gender and class expectations, and against the limitations of their body [10]. Identifying oneself as ‘bulimic’ may represent an appeal to higher values such as subversiveness or rebellion. Identifying with one’s illness may serve to establish connection with similar others, resulting in a shared social identity [11]. Identity-based support with like-minded individuals can aid recovery and can encourage a shift from identifying with the disorder to engaging in treatment [11]. Nonetheless, support groups may have unintended adverse consequences, since participants may construct a collective illness identity that hinders, rather than promotes, recovery [12].

A study revealed that 5% of Maltese young people aged 10 to 16 have an ED [13], as cited in [14]. The increase in younger people seeking help for ED is also reflected in international trends [14], suggesting that problems related to eating are on the rise. There is a shortage of qualitative research focusing on the clients’ perspectives in relation to the causes and factors that contribute to ED and recovery [15]. Research established the need to understand factors influencing recovery and assess how prevention strategies can target specific risk factors for the development of an ED [16]. A gap in knowledge exists in relation to the subjective account of individuals with bulimia. It is unclear how integrating the disorder into one’s identity may affect treatment. To address these aforementioned gaps, this research aimed to explore perceptions of bulimia from the perspective of women who recovered from the disorder. Another aim was to explore how social and cultural issues related to the Maltese context affect participants’ perceptions of bulimia. Finally, this study aimed to understand whether bulimia affects the woman’s identity, and whether one’s self-concept and identity changes along the progression of the illness and after recovery. It is hoped that this research can increase qualitative knowledge available in the field. Bulimia remains under-theorized and underrepresented in research [10].

Methods and Materials

A qualitative approach was deemed the most appropriate for reaching the intended aims. Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) as described by Braun & Clarke [17] was used to identify patterns of meaning across the dataset, and to provide answers to the questions being addressed. Leventhal et al’s Self-Regulation Model of Health and Illness (SRM, 1984) was used to create in-depth understanding of the different components that formulated participants’ own illness perceptions. The conceptual framework underlying this study was social constructionism. Social constructionism adopts a critical stance to understanding the nature of knowledge and meaning in the world and argues that an understanding of the world is relative to history and culture [18]. Sociocultural forces construct knowledge, and knowledge cannot be grounded in one observable, external reality but is a product of human thought [18]. The ontological position was that of critical realism. The assumption is that although ‘authentic’ reality helps in the production of knowledge, knowledge is influenced by society, culture and history, amongst other things. Data becomes a representation of experience and not a direct replication of it [19].

The sampling strategy and participant recruitment

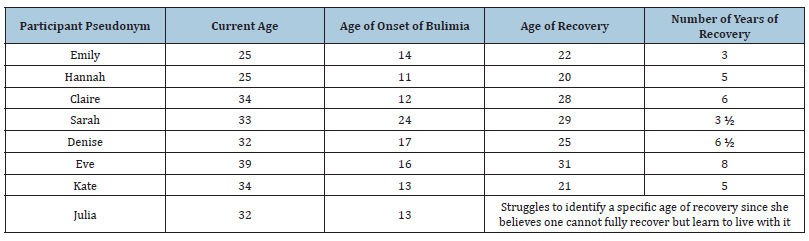

Purposive sampling was used. The eligibility criteria included females who are over 18 and who had recovered from the disorder for at least 2 years. Female participants were recruited given that the local prevalence of eating disorders is higher in this group [13]. A research letter containing detailed information about the nature of the study was disseminated to specialized treatment centers. Interested individuals approached the researcher directly via phone or electronic mail. This process resulted in a total of 8 participants. Participant details can be found in (Table 1).

Table 1: Participant characteristics.

Data collection and analysis

Data was collected using semi-structured interviews and analyzed according to the six-phase process of Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) described by Braun & Clarke [17,20]. RTA is not a rigid series of stages that offers only ‘either or’ choices to coding [17]. Codes may be determined on the basis of a pre-existing theory, from familiarization with the data itself (i.e., inductive approach), or through a combination of both approaches [21]. An inductive approach was also incorporated so as to allow for the generation of themes which were unrelated to Leventhal et al’s Model.

Credibility and trustworthiness

Lincoln & Guba [22] explain the concept of trustworthiness through the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Reflective thoughts emerging through the repeated immersion with the data were noted and revisited at subsequent stages. This ensured that the initial data engagement respected the concept of transparency while remaining faithful to participants’ narrative [23]. Memos and diagrams were used to develop connections and further define the formation of themes. Emergent themes were discussed between two researchers and checked with participants to ensure they reflected the participants’ voices [24].

Results

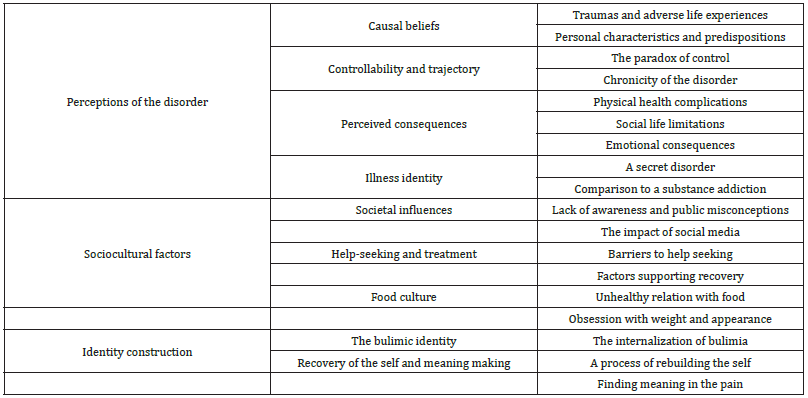

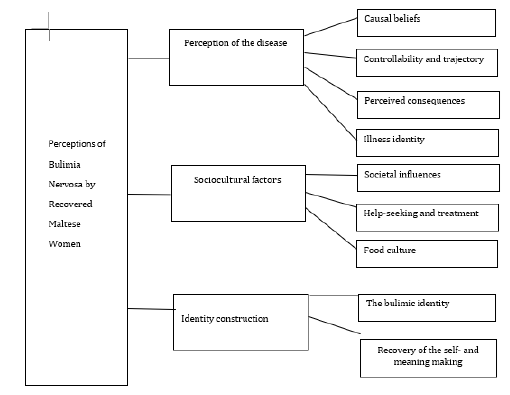

Data analysis led to the emergence of three Global themes. A breakdown of all themes can be found in Table 2, together with an illustration of the Global themes in (Figure 1).

Table 2:Global themes, organizing themes and basic themes.

Figure 1: Global themes.

Global theme 1: perceptions of the disorder

The first theme is related to the participants’ perceptions of bulimia nervosa. It is split into organizing themes pertaining to specific components outlined in Leventhal’s model.

Causal beliefs:Traumas & adverse life experiences: Most participants could identify specific traumas or adverse life events which were believed to have triggered the disorder. Bulimic behaviors such as purging served either as a way of regaining control over oneself and one’s body, or as a way of dealing with overwhelming emotions. Sarah recounts how a traumatic accident resulted in a severe injury which left a permanent scar on her body, resulting in highly distressing emotions and feelings of lack of control over her health and body. I thought I’m gonna be scared for life, and I needed to find control elsewhere. I believe that triggered it. On the other hand, Kate explains that: I had a very tough childhood so that was maybe a trigger. My refuge from overwhelming anxiety was throwing up. Personal characteristics & predispositions: Personal characteristics, psychological factors or biological predispositions were perceived to increase participants’ susceptibility to developing bulimia. Personality traits that were perceived to increase susceptibility included feelings of inferiority, low self-esteem, high self-consciousness, and heightened anxiety. One participant felt that the difficulty regulating intense emotions contributed to her unhealthy relationship with food. Other perceived contributing factors were psychological issues coupled with stressful life events that triggered the disorder. Sarah said: I am probably, and I can see it even in my family, prone to having an addictive personality. In my case it was bulimia. Then, it developed further because my parents separated when I was very young. Possibly, life stressors further contributed to this. Emily complements this by sharing: Maybe it’s true that the issue may start from wishing to lose weight, but in reality, it’s much deeper than that. I mean, its trauma, childhood, your experiences, personality.

Controllability & trajectory:The Paradox of Control. Most participants thought they had control over the bulimia when symptoms started. This perception stemmed from the ability to manage emotions and weight as a result of bulimic behavior. Nonetheless, control was immediately lost on progression of the disorder. This was described as a form of paradox, in that the same disorder that initially provided them with a sense of control transitioned into a problem that spiraled out of control. At first, I really thought that it is what is giving me control and that I can stop literally whenever I want [...] Then kind of you start realizing that listen, I don’t have control in reality. So, it becomes the other way round where your bulimia actually starts controlling you. Chronicity of the Disorder. Participants explained that it was difficult to perceive a timeline or to envisage a duration for the course of their disorder. The common consensus was that bulimia was not perceived as a temporary disorder, since the process of recovery is non-linear, challenging, and characterized by a number of relapses. You feel it’s impossible to get out of it.

Perceived consequences:Physical Health Complications. Most participants claimed the disorder has negatively impacted their physical health, with repercussions still carried to this day, even after recovery. I remember my teeth were very, very weak because of acid and everything. To this day, I have super sensitive teeth. Social Limitations. Another prevalent theme was the negative implications on the bulimic’s social life, resulting in withdrawal and social isolation. The desire to hide symptoms and the preoccupation of not finding a bathroom to purge after eating made socializing stressful. Back then, for instance, I didn’t go out, I didn’t buy any clothes. I just used to go to school, lock myself inside, read sometimes...The characters in the book became my social life. I didn’t use to go out, or else if I did go out, I needed to ensure the place had an accessible bathroom. Emotional Consequences. The emotional implications were not perceived to be exclusively negative. A feel-good factor was experienced during purging, exercising or other compensatory behaviors, making the emotional consequences of bulimia “an emotional rollercoaster” (Sarah). Highs were short-lived and followed by unpleasant emotions, predominantly guilt, shame, depression and anxiety. As much as it made me feel good right after vomiting, the effect was immediate pleasure. Immediate reward, kind of.

Illness identity:‘Illness identity’ refers to labels’ individuals assign to their symptoms to make sense of the disorder. It comprises the way the person thinks about oneself and how the disorder dominates the individual’s life. A Secret Disorder. An emergent pattern was the element of secrecy that characterizes bulimia. Participants kept their disorder hidden from significant others. Bulimia was perceived as being different to other ED given that weight can be maintained, making it less noticeable to others. Another reason for secrecy was the realization that their behavior was not typical. Bulimia was accompanied by feelings of extreme loneliness and isolation. Extensive planning was required in order to maintain secrecy of the disorder. Participants recounted how they acquired detailed strategies over time, becoming “experts” at keeping behaviors hidden. When you’re an “expert bulimist?”, I don’t know what to call it... But you know exactly which foods will hurt when you throw up. You know exactly what you need to eat, and how you need to eat, and how much you should drink water while you’re eating so throwing up is easier. Comparison to Substance Addiction. Bulimia was likened to an addictive disorder involving a complete lack of control over the substance, which in their case, was food. Conclusively, recovery involved a number of relapses. In reality with an eating disorder, especially bulimia which is a binging cycle, you have an addiction. But unlike any other addiction, you can’t stop eating, you need food to survive.

Global theme 2: sociocultural factors

This theme concerns the experience of living with bulimia within the local context. It comprises three sub-themes as outlined below.

Societal influences:Lack of Awareness & Public Misconceptions. A common feeling of lack of awareness, knowledge or misconceptions in relation to ED was prevalent. Although society was perceived as becoming more accepting of mental health difficulties, most felt this was not the case with bulimia.

Even nowadays I don’t think there is enough awareness. There is awareness on drug addiction…on depression. But, eating disorders, I don’t see that. Public knowledge was perceived as being limited. People do not grasp the complexity behind the development of ED. Some felt blamed and misunderstood by those around them. Not many people can understand how emotionally distressed you are about it when you’re going through it. People start saying… sort of “this is all foolishness”, and “listen, get yourself together”, which is not easy. The Impact of social media. Participants commented on the problem of social comparison and the negative role social media plays in exacerbating the disorder. Low self-esteem and feelings of inferiority are an integral part of bulimia. These are often reinforced by social media content which was described as a trigger. Nowadays on Instagram everyone’s into fitness [...] There were a lot of times when I would for example be scrolling through Instagram and like, I re-experience the urges then. Three of the older participants believe that the current social media climate has become increasingly scrutinizing, leading to larger challenges in relation to managing social comparisons. I don’t want to imagine what young people go through right now, because back then, social media didn’t exist….I cannot imagine how it is for youngsters nowadays, that you’re constantly being told “you need to change that”, “you need to dress like that”, “you need to be size zero.”

Help-seeking and treatment:This theme encapsulates the help-seeking behavior and treatments available. Lack of Specialized Services. A shared consensus was that help-seeking was difficult due to a lack of specialized facilities. Older participants recall how specialist services were either non-existent or less developed at the time they were unwell. My mum started worrying and she took me to the doctor [...] However there was no awareness at all, so much so that he told her “Just take her to a nutritionist.” Some experienced inappropriate comments from healthcare professionals, which they attributed to lack of knowledge about ED, resulting in mismanagement of the problem, a negative treatment experience or an exacerbation of symptoms. I went to this psychiatrist, and he asked whether I induced vomiting. And he told me “Great”, because otherwise you would have more severe problems.” [...] So literally, the first thing I did when I went home was trying to vomit. Two participants could not find the appropriate support and eventually worked towards recovery without professional help. Barriers to Help-seeking. Negative healthcare experiences and lack of specialized services lead most individuals to seek private treatment. Nonetheless, financial strains were a barrier to treatment. I had to pay for my personal therapy myself, which is not cheap. So that is another limiting factor, how much you can pay, because maybe I could but other people cannot, who knows? Factors Supporting Recovery. All participants believe that support was valuable in reinforcing their willpower to recover. Other factors that helped in recovery were hobbies or engaging in pleasurable activities including music, sport, yoga, Pilates, and meditation. Obviously having a good support system around, you will help, so I’m forever thankful to my parents that no matter how much they struggled with the situation, they still kept there, following it with me and saying “we can do it.”

Food culture:Unhealthy Relationship with Food. A common perception was that the local society has an unhealthy relationship with food, with the mentality of over-indulgence and excessively large food portions. This contributed to excessive eating. Comments from significant others encouraging them to eat was another contributing factor. This reinforced the need to engage in compensatory behaviors to ease the guilt of overeating. Coming from a family which is like most Maltese people who eat a lot [...] it sorts of impacted the way I view food, because I never could understand how much a normal person should eat. What is healthy? Is this normal? The local society does not promote eating healthily, and the lack of availability of healthy foods and prices for healthier options makes it difficult for individuals who are struggling with eating problems, or who are in recovery, to opt for alternative options. Interestingly, Kate commented on a local and prevalent attitude of using food as a reward or comfort, creating the need to over-indulge to cope with unpleasant emotions. So, I think with food… even if you’re feeling sad, just order a pizza….I think it’s quite difficult, because we teach our children that food is a kind of therapy, that you can comfort eat, but then you can’t get fat. So, it is kind of a recipe for disaster. Obsession with Weight and Appearances. A prevalent perception was the view that the local society places too much emphasis on weight and physical appearance. This may perpetuate and reinforce an individual’s problematic relationship with food. Shouldn’t one focus more on the health perspective? Instead of just, you know, how we look, but also on what’s happening internally? Because I’m sure that at the point when I was looking for my best [bulimia], inside I had so many issues because of what I was doing to my body.

Global theme 3: identity construction

The final theme revolves around how an individual’s personal identity is perceived to be affected by bulimia. It encompasses two organizing themes.

The bulimic identity:The Internalization of Bulimia. The absolute majority of participants perceived bulimia as a disorder which consumes the person, to the point of becoming internalized into one’s sense of self. It becomes a defining factor of the self, blurring one’s self-concept. At that time, I used to see darkness around me [...] It’s like for me it was my life and I didn’t know who Emily was, you know? You would be without a personality kind of, because it consumes you completely. The integration of the disorder within the self was a major challenge to recovery since some participants were afraid of losing themselves if the bulimia was no longer present. I don’t miss it… but it was kind of a part of me. Even when I started recovery, there was a time where I was scared because that is all I knew. The secrecy of the disorder and the need to keep it concealed from the public eye resulted in a discrepancy between the private and public self. It was totally two different people; it was a double identity.

Recovery of the self & meaning makingA Process of Rebuilding the Self. As mentioned above, the internalization of the disorder makes recovery challenging Therefore, “that is the largest problem when you start healing from it, that you would be totally lost without it.” (Claire). Seven participants believe bulimia cannot be cured but treated, implying that some traits remain ingrained within the person. Recovery was perceived as a process of stopping the binge-purge cycle and learning to control the symptoms by developing healthier behaviors and alternative coping skills.

You carry it with you all your life, at least this is how it is for me…. So, I can’t really say ‘I’m fully recovered.’ Some demons just never let you go. You just control them, rather than letting them control you. Recovery was perceived as a process of finding oneself, identifying and managing triggers and working on one’s self-concept to strengthen one’s sense of self. This enabled the development of a new personal identity which does not center around bulimia. It allowed participants to reconsider how they wanted to define themselves and to recreate meaning. Although external motivators such as hobbies were helpful, the willpower and desire to recover needs to develop intrinsically within the selfcrucial since no external factor can be powerful enough to maintain recovery. The help has to come from within [...] I mean, at the point of recovery, I knew that I wanted to get better.”

Finding meaning in the pain:Most participants feel that bulimia helped them recognize what was truly important in life. Despite not wishing to go through the experience again, a sense of gratitude for what they have been through helped contributed to the person they are today. This suggests they were able to find meaning in their struggles and came out stronger as a result. I think I developed a fondness for life, because so much of my life was wasted, you know, looking down at a toilet. [...] So I would say that bulimia is like a very, very dark shadow, but a shadow appears because there is the sun. So, you know, it’s like this image in my mind that it’s been a dark shadow, but the shadow has its own rays of sunlight, you know, of which I’m very grateful.

Discussion

Perceptions of bulimia

Causal Beliefs. Participants predominantly attributed the development of bulimia to personality characteristics or psychological factors, which predisposed them to developing disordered eating behavior. This is in line with previous research highlighting how negative affect predicts the onset of eating disorders and how negative self-evaluation and low self-esteem contribute to eating disorder pathology [25]. It is also similar to findings of previous research suggesting that individuals with bulimia primarily attribute the disorder to psychological causes [26]. Participants seemed to show a retrospective awareness that adverse life experiences or traumas triggered a need to regain control over themselves or their body, contributing to the development of the eating disorder. This echoes findings that early experiences of traumatic events are associated with eating disturbances later in life [27]. In line with the Diathesis-Stress hypothesis [28], the causes of bulimia were predominantly attributed to psychological factors but the risk for its development was exacerbated by negative life events. Controllability & Trajectory. Participants perceive bulimia as a cyclical and chronic disorder. Symptoms may become retriggered if they are not managed effectively, even after recovery. Although the perception of control was highly felt during the early onset of symptoms, the loss of control was experienced as the disorder developed further. This contrasts with DeJong et al. [26] study where the perception of control was high. Participants in the latter quantitative study were not recovered, possibly accounting for these differences. Perceived Consequences. Bulimia was perceived to have a multitude of negative consequences on participants’ lives on a physical, social, and psychological level. Some physical implications are irreparable or continue to have ramifications to this day. Participants expressed increased social isolation due to the need to conceal binging and vomiting. Similar findings were disseminated by Broussard [29] whereby secrecy, isolation, and living in fear were found to represent women’s experiences of bulimia. The negative emotional consequences were perceived as an “emotional rollercoaster” characterized by low mood, guilt and shame coupled with brief moments of positivity and emotional release once compensatory behaviors were employed. The bingepurge cycle has been perceived as a way of regaining control and reinstating feelings of calmness and satisfaction despite the presence of shame and guilt [30]. Illness Identity. Bulimia was perceived as being different to anorexia in allowing the individual to maintain an average weight and facilitate the possibility of secrecy. The physical symptoms are not easily observable by others, making detection difficult [31]. The secretive nature leads to intense feelings of loneliness and isolation, accompanied by a need for extensive planning as identified in previous literature whereby isolating oneself and experiencing internal struggles was reported to be part of the disorder [29]. The inability to control food as experienced during binges was likened to the lack of control over a substance that occurs in other forms of addictive behavior. This addictive component consumes the person, making it extremely difficult to stop the binge/purge cycle. There is support for the notion that bulimia can be described as an addiction-like eating behavior [32].

The experience of bulimia within the local sociocultural context

Societal Influences. A common consensus was the lack of awareness about ED within the local context. Although society was perceived to have made notable improvements in reducing stigma towards mental health difficulties, this acceptance does not extend to bulimia. Various misconceptions prevail. While the public was perceived to view bulimia as an inability to control food and a wish to lose weight, participants believe this is a superficial explanation. The public is unaware of the underlying psychological factors that could trigger the disorder. The perception was that of a self-blame society, making them feel misunderstood by the people around them. Research examining public attitudes revealed that individuals with ED were held more personally responsible for their illness and were ascribed more negative personality characteristics compared to people with depression or Type 1 diabetes [33]. O’Connor et al found that ED were perceived as a failure of self-discipline rather than being attributable to psychological problems and were more stigmatized than other physical or mental health conditions [33].

Negative perceptions add to the secrecy and isolation which already characterizes bulimia. This finding is particularly relevant in a small country with tight-knit communities such as Malta where stigma towards mental health problems continues to exist [34]. Rates of internalized stigma towards mental illness were found to be significantly higher in Malta when compared to other countries [35]. Moreover, negative stereotypes, social rejection, and attributions to personal responsibility promote blame and further stigmatization [36] contributing to silent barriers to treatment [37]. Social media was a trigger since the online climate was perceived as typically characterized by obsessions with physical appearance and the promotion of thin ideals, leading to feelings of inferiority. Participants believe it has become increasingly toxic over the years. Social media pressures were perceived to be much worse than some had experienced in their own time. Exposure and engagement with body image content emphasizing a thin ideal on social media platforms is a potential trigger for ED symptoms, anxiety and depression [38]. It is important to consider the role of social media in exacerbating the risk of eating disorder symptomatology among young people. Help-seeking & Treatment. In most cases, the first port of call was seeking help from a primary healthcare setting or mental health professional. Services for ED treatment was perceived to be lacking, making help-seeking difficult. ‘Dar Kenn għal Saħħtek’ (DKS), the only specialized treatment center for eating disorders in Malta opened in 2014, meaning that most participants have battled the disorder in a time where local services were either non-existent or in the early phases of development. Participants expressed the view of lack of awareness about eating disorders among healthcare professionals locally, claiming that their symptoms were mishandled by the healthcare system. This contributed to a negative treatment experience, or a worsening and retriggering symptom. This is in line with previous research whereby individuals with ED reported a lack of eating disorder knowledge, understanding and experience among primary care professionals [39]. These problems seem to exist even in countries with much larger healthcare systems than Malta’s. Healthcare professionals perceive eating disorders as too complex and time consuming, with some being reluctant to work with this population [40].

ED requires specialized treatment [41]. Most participants acknowledged the benefits of DKS and welcomed its introduction as a step forward in our local healthcare. Yet, concerns about the efficacy of the services remained, mostly due to long wait lists. Individuals who experience a relapse and require support, or those whose symptoms are not severe may not be given immediate attention. Specialist services have often been described as significantly under-resourced and overburdened, resulting in prolonged illness or no treatment being given [41]. This resonates with the experience of two participants who did not find the appropriate support and worked their own way towards recovery. Although psychotherapy from private institutions was perceived as beneficial, the cost of service was a barrier to treatment. Social support and health outlets such as yoga and Pilates were perceived as offering holistic benefits. The importance of personal willpower and motivation to change was deemed essential. Local Food Culture. A collective view perceived the local society as having an unhealthy relationship with food, with a mentality of over-indulgence and large food portions, resulting in a high local prevalence of obesity. These factors contributed to increased guilt which was heightened whenever participants ate all the food on their plate. Comments encouraging them to keep eating, which are often common in the local culture, increased the risk of compensatory behaviors. The prevalence of unhealthy foods on the Maltese table remains. The availability of healthier food options is not strongly observed in Malta. Living in an obesogenic environment dominated by energydense food choices is a challenge for individuals who are struggling to maintain healthy eating habits [42]. A prevalent comment was the tendency to use food as a reward, or comfort for negative emotions. Food thus becomes a way of regulating emotions. This notion features prominently in theories of emotional eating and is included in various psychotherapeutic approaches to ED treatment [43]. Individuals with bulimia tend to use more dysfunctional strategies to regulate emotions [44]. Binging may be a way of blocking, dissociating, or escaping negative emotional states [43]. It might be useful to explore the kind of messages about food and eating are being transmitted to younger generations.

The impact of bulimia on maltese women’s identity

The Bulimic Identity. Participants experienced bulimia as a disorder which consumes the individual, to the extent that it becomes internalized into one’s identity. This is in line with the illness identity state described as engulfment or when individuals start to completely define themselves in terms of their disease [45]. This internalization challenged participants’ process of recovery since most felt ambivalent to recover out of fear that part of themselves will be lost if bulimia is no longer present. ED are often ego syntonic and overcoming them is perceived to conflict with personal values [5]. This integration of a disorder with the self is often a key component in the maintenance of ED [46]. This internalization provides a sense of security and contributes to an ambivalence towards recovery despite the willingness to recover [29]. Despite the integration of bulimia as part of the self, participants realized that their behavior was ‘atypical’, hence the need to keep it hidden. This resulted in a split between the ‘public’ self, through which the person tried to assume a ‘normal’ identity around others and the ‘private’ self, characterized by bulimic symptoms and negative affect when the person is alone. This is similar to the concept of “double life” as discussed by Pettersen et al. [47] or the dichotomy between being active and social versus experiencing shame for bulimic behavior and constant fear of exposure and stigmatization. Acknowledging the costs created by this “double life” and reducing shame may be the first steps towards recovery [47].

Recovery of the Self. The aforementioned internalization of bulimia is an important consideration in recovery. Most participants regard bulimia as a disorder which is not fully recoverable. Certain behaviors or traits remain ingrained within the person. Recovery was perceived as a process of learning to control or stop the symptoms by developing alternative coping skills. An interesting finding was the distinction between the terminology employed by different participants in order to define their sense of self and identity after recovery. Specifically, the majority seem to hold the idea that “a sufferer will always be a sufferer”. Thus, bulimia is a chronic disorder which can be treated rather than cured. Others no longer identify themselves with the disorder. One participant highlighted how referring to herself as “a person who used to have bulimia” is preferred to the term “ex-bulimic” since the former allows for a separation between the disorder and one’s personal identity. Recovery can be a very subjective experience as reflected in the multitude of definitions of recovery in ED literature [48].

Building one’s self-esteem and strengthening the sense of selfworth were crucial aspects of the recovery process. A reevaluation of life priorities, and the development of a new identity which did not center around bulimia motivated participants to start their recovery process as identified by Pettersen et al. [49]. These factors have been described as representing psychological processes related to grief, commitment and reconciliation [49]. The individual needs to grieve and accept the losses resulting from a long-standing disorder and move towards a reconciliation of a new life and self [49]. These findings shed light on the importance of managing psychological changes that may arise in recovery. A shift in identity was experienced following recovery. A participant felt relieved that her internal struggles did not harm significant others. This perspective may indicate feelings of selflessness or the tendency to prioritize others’ needs over one’s own. Selflessness is a predisposing factor for ED. Individual may feel unworthy of giving attention to oneself [48]. Promoting feelings of self-love and self-care could aid recovery. All participants commented on the positive aspects that emerged from bulimia, despite the many hardships endured. The disorder helped them recognize their life values. The bulimia made them the strong people that they are today and helped them find meaning in the struggles they have been through. This shows the element of resilience. Possibly, the initial engulfment by bulimia has shifted not only to acceptance (i.e., accepting the disorder as part of one’s identity), but also to enrichment or the ability to recognize positive life changes and benefits to one’s identity caused by the disorder as identified in previous literature [45].

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was that it bridged an existing gap in literature since individuals with bulimia are often underrepresented in research [10]. It adds to the limited qualitative studies on the disorder and sheds light on the different aspects that should be targeted by healthcare professionals to enhance the quality of existing treatment services. The main limitation was the small sample. Recruiting participants proved challenging. A larger sample size would have added more richness and understanding to the topic in question.

Recommendations

Most recommendations were suggestions provided by research participants. Healthcare professionals could be provided with basic training on detecting ED symptoms and how to communicate with this population. An initial positive treatment experience might facilitate the process of a referral to specialized services and increased motivation for change. Psychologists play a vital role in the treatment of ED (American Psychological Association, 2010) and can be an integral part of a multidisciplinary team to provide holistic care. The importance of ‘unpacking’ the psychological issues underlying bulimia cannot be stressed enough. Recovery can only occur if the individual develops the readiness and motivation for it. Incorporating Motivational Interviewing [50] and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy principles [51] can bolster readiness for change. A systemic approach is important for the assessment and management of individuals with bulimia.

Proposals for policymakers

Policies should focus on developing or upgrading services that address the unique needs of this population. It is recommended to include education on mental health problems in academic curricula so that exposure and education about ED or psychological difficulties in general are transmitted to younger generations from an early age. The benefits of this may be twofold. Initial symptoms of ED may be detected at an early stage before progressing to a state requiring intensive treatment. Education may lead to increased awareness on ED among the general public with the hope of reducing stigma in help-seeking behavior. Nationwide educational campaigns should focus on disseminating information about eating behaviors and healthier ways of relating to food, rather than to sole provision of dietary guidelines alone. Recommendations have been put forth for specialized services to be offered within the community rather than specific treatment centers with the hope of decreasing shame and stigma in relation to help-seeking. This may be particularly useful to individuals who have recovered but require brief support to decrease the chance of relapse. Given the limited number of professionals specialized in ED, offering training incentives might be helpful in encouraging healthcare professionals to familiarize themselves with the field of ED

Recommendations for future research

The classification, diagnostic criteria, and assessment measures for ED have been almost entirely informed by research conducted with female samples [52]. Future research can look into the experiences of males impacted by eating disorders and assess their beliefs about eating pathology. It might be interesting to conduct comparative studies exploring potential gender differences in perceptions of bulimia. Further research could explore healthcare professionals’ understanding of ED and their experiences of working with this group. This can shed light onto the kind of training required to increase the effectiveness of local services. It is worth exploring whether perceptions of bulimia change over time through the adoption of a longitudinal approach. Research could explore beliefs about bulimia within the lay population [53-60].

Conclusion

The experience of having bulimia is multi-layered, complex, and devastating to the individual. Individuals with bulimia need to be seen, heard, and acknowledged within society [61-68]. It is hoped that in its smallness and limitations, this research will contribute to raising awareness about this and other eating disorders, both amongst professionals and possibly the general public.

References

- Alves SAA, Oliveira MLB (2018) Sociocultural aspects of health and disease and their pragmatic impact. Journal of Human Growth and Development 28(2):

- Leventhal H, Nerenz D, Purse J (1984) Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Baun SE, Taylor JE, Singer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health: social psychological aspects of health Hillsdale, Earlbaum pp. 219-252.

- Bruch H (1973) Eating disorders: Obesity, anorexia nervosa, and the person within. Routledge, UK.

- Dada G, Izu S, Montebruno C, Grau A, Feixas G (2017) Content analysis of the construction of self and others in women with bulimia nervosa. Frontiers in Psychology 8.

- Mulkerrin Ú, Bamford B, Serpell L (2016) How well does anorexia nervosa fit with personal values? An exploratory study. Journal of Eating Disorders 4(1).

- Martins IJ (2020) Appetite dysregulation and the apelinergic system are connected to global chronic disease epidemic. Series of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism 1(3): 67-69.

- Martins IJ (2018) Increased risk for obesity and diabetes with neurodegeneration in developing countries. Top 10 Contribution on Genetics.

- Martins IJ (2016) Anti-aging gens improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global population. Advance in Aging Research 5(1): 9-26.

- Martins IJ (2015) Appetite dysregulation and obesity in western countries Ian J Martin. In: Emma J (Ed.), LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Eli K (2017) Distinct and untamed: Articulating bulimic identities. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 42(1): 159-179.

- McNamara N, Parsons H (2016) Everyone here wants everyone else to get better: The role of social identity in eating disorder recovery. British Journal of Social Psychology 55(4): 662-680.

- Koski JP (2013) I’m just a walking eating disorder: The mobilisation and construction of a collective illness identity in eating disorder support groups. Sociology of Health & Illness 36(1): 75-90.

- Kenn GS (2020) Facebook page.

- Calleja C (2020) 5% of young people aged 10 to 16 have eating disorders. Times of Malta.

- Cruzat MC, Díaz CF, Escobar KT, Simpson S (2015) From eating identity to authentic selfhood: Identity transformation in eating disorder sufferers following psychotherapy. Clinical Psychologist 21(3): 227-235.

- Van FEF, Van MA , Cowan K (2016) Top 10 research priorities for eating disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry 3(8): 706-707.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2019) Thematic analysis - A reflexive approach. The University of Auckland, New Zealand.

- Burr V (2015) Social constructionism. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 22(2): 222-227.

- Willig C (2012) Perspectives on the epistemological bases for qualitative research. In: Cooper H (Ed.), APA Handbook of Research Methods in psychology, Foundations, planning, measures, and psychometrics, American Psychological Association 1: 5-21.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101.

- Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V, Braun V (2017) Thematic Analysis. In: Willig C, Stainton RW (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, US.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage, US.

- Yardley L (2016) Demonstrating the validity of qualitative research. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12(3): 295-296.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ (2017) Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16(1): 1-13.

- Keel PK, Forney KJ (2013) Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders 46(5): 433-439.

- DeJong H, Hillcoat J, Perkins S, Grover M, Schmidt U (2011) Illness perception in bulimia nervosa. Journal of Health Psychology 17(3): 399-408.

- Backholm K, Isomaa R, Birgegård A (2013) The prevalence and impact of trauma history in eating disorder patients. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 4(1): 22482.

- Zuckerman M (1999) Diathesis-stress models. Vulnerability to Psychopathology: A Biosocial Model pp. 3-23.

- Broussard BB (2005) Women’s experiences of bulimia nervosa. Journal of Advanced Nursing 49(1): 43-50.

- Blythin SPM, Nicholson HL, Macintyre VG, Dickson JM, Fox JRE, et al. (2020) Experiences of shame and guilt in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: A systematic review. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 93(1): 134-159.

- Keel PK (2017) Eating disorders. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Meule A, Von RV, Blechert J (2014) Food addiction and bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review 22(5): 331-337.

- O’Connor C, McNamara N, O’Hara L, McNicholas F (2016) Eating disorder literacy and stigmatizing attitudes towards anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder among adolescents. Advances in Eating Disorders 4(2): 125-140.

- Agius M, Falzon AF, Pace C, Grech A (2016) Stigma in malta: A mediterranean perspective. Psychiatria Danub 28(1): 75-78.

- Krajewski C, Burazeri G, Brand H (2013) Self-stigma, perceived discrimination and empowerment among people with a mental illness in six countries: Pan European stigma study. Psychiatry Research 210(3): 1136-1146.

- Puhl R, Suh Y (2015) Stigma and eating and weight disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports 17(3).

- Griffiths S, Mond JM, Murray SB, Touyz S (2014) The prevalence and adverse associations of stigmatization in people with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders 48(6): 767-774.

- Fitzsimmons CEE, Krauss MJ, Costello SJ, Floyd GM, Wilfley DE, et al. (2019) Adolescents and young adults engaged with pro-eating disorder social media: Eating disorder and comorbid psychopathology, health care utilization, treatment barriers, and opinions on harnessing technology for treatment. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 25: 1681-1692.

- Grave RD (2011) Eating disorders: Progress and challenges. European Journal of Internal Medicine 22(2): 153-160.

- Walker S, Lloyd C (2011) Barriers and attitudes health professionals working in eating disorders experience. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 18(7): 383-390.

- Johns G, Taylor B, John A, Tan J (2019) Current eating disorder healthcare services – the perspectives and experiences of individuals with eating disorders, their families and health professionals: systematic review and thematic synthesis. BJPsych Open 5(4).

- Corsica JA, Hood MM (2011) Eating disorders in an obesogenic environment. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 111(7): 996-1000.

- Meule A, Richard A, Schnepper R, Reichenberger J, Georgii C, et al. (2019) Emotion regulation and emotional eating in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Eating Disorders 29(2): 175-191.

- Svaldi J, Griepenstroh J, Tuschen CB, Ehring T (2012) Emotion regulation deficits in eating disorders: A marker of eating pathology or general psychopathology? Psychiatry Research 197(1-2): 103-111.

- Van BL, Luyckx K, Goossens E, Oris L, Moons P (2018) Illness identity: Capturing the influence of illness on the person’s sense of self. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 18(1): 4-6.

- Gregertsen EC, Mandy W, Serpell L (2017) The ego syntonic nature of anorexia: An impediment to recovery in anorexia nervosa treatment. Frontiers in Psychology 8.

- Pettersen G, Rosenvinge JH, Ytterhus B (2008) The double life of bulimia: Patients’ experiences in daily life interactions. Eating Disorders 16(3): 204-211.

- Bardone CAM, Hunt RA, Watson HJ (2018) An overview of conceptualizations of eating disorder recovery, recent findings, and future directions. Current Psychiatry Reports 20(9).

- Pettersen G, Thune LKB, Wynn R, Rosenvinge JH (2012) Eating disorders: Challenges in the later phases of the recovery process. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 27(1): 92-98.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (1992) Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change (2nd edn), The Guilford Press, US.

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG (2016) Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd edn), Guilford Press, US.

- Mitchison D, Mond J (2015) Epidemiology of eating disorders, eating disordered behavior, and body image disturbance in males: A narrative review. Journal of Eating Disorders 3(1).

- Braun V, Clarke V (2013) Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage, US.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2020) Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern‐based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 21(1): 37-47.

- Chan RCH, Mak WWS (2016) Common sense model of mental illness: Understanding the impact of cognitive and emotional representations of mental illness on recovery through the mediation of self-stigma. Psychiatry Research 246: 16-24.

- Creswell JW (2013) Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. SAGE, US.

- Finlay L (2008) A dance between the reduction and reflexivity: Explicating the phenomenological psychological attitude. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 39(1): 1-32.

- Higbed L, Fox JRE (2010) Illness perceptions in anorexia nervosa: A qualitative investigation. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 49(3): 307-325.

- Jacob SA, Furgerson SP (2012) Writing interview protocols and conducting interviews: Tips for students new to the field of qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 17(42): 1-10.

- Lavender JM, De Young KP, Anderson DA (2010) Eating Disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q): Norms for undergraduate men. Eating Behaviors 11(2): 119-121.

- Marcos YQ, Cantero MCT, Escobar CR, Acosta GP (2007) Illness perception in eating disorders and psychosocial adaptation. European Eating Disorders Review 15(5): 373-384.

- Mond JM (2014) Eating disorders mental health literacy: An introduction. Journal of Mental Health 23(2): 51-54.

- Patton MQ (2002) Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (3rd edn), Sage Publications, US.

- Rodgers RF, McLean SA, Paxton SJ(2015) Longitudinal relationships among internalization of the media ideal, peer social comparison, and body dissatisfaction: Implications for the tripartite influence model. Developmental Psychology 51(5): 706-713.

- Stice E, Gau JM, Rohde P, Shaw H (2017) Risk factors that predict future onset of each DSM-5 eating disorder: Predictive specificity in high-risk adolescent females. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 126(1): 38-51.

- Striegel MRH, Bulik CM (2007) Risk factors for eating disorders. American Psychologist 62(3): 181-198.

- Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, Tantleff DS (1999) Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association.

- Willig C (2013) Introducing qualitative research in psychology (3rd edn), Mcgraw Hill Education, Open University Press, UK.

© 2022. Pamela Portelli. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)