- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Approaches in Cancer Study

The Effects of Radiation on Cancer Immunology

Lyna Pham1a, Ava Wang1b, Chikezie O Madu2 and Yi Lu3*

1Departments of Biology and Advanced Placement Biology, White Station High School, Memphis, TN 38117, USA, lynahx@gmail.com

2Departments of Biology and Advanced Placement Biology, White Station High School, Memphis, TN 38117, USA, daomiwang@gmail.com

3Departments of Biology and Advanced Placement Biology, White Station High School, Memphis, TN 38117, USA, maduco@scsk12.org

4Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN 38163, USA, ylu@uthsc.edu

*Corresponding author: Yi Lu, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Cancer Research Building, Room 258, 19 South Manassas Street, Memphis, TN 38163, USA, Email: ylu@uthsc.edu

Submission: April 02, 2020Published: May 14, 2020

ISSN:2637-773XVolume4 Issue4

Abstract

Cancer immunology largely depends on the effects of radiation therapy (RT). RT is predominantly focused on inducing tumor cell death, triggering anti-tumor immune responses, and generating DNA damage. Although the immune system has the ability to recognize and reject specific tumors, some tumors acquire characteristics that allow them to evade immune destruction by expressing a highly immunosuppressive microenvironment and decreasing their immunogenicity. Exposing the tumor site to radiation stimulates tumor-specific antigens, making them perceptible to the immune system and stimulating the priming and activation of cytotoxic T cells. In addition, tissue damage caused by radiation applied to the tumor microenvironment moderates a release of inflammatory cytokines that assists in leukocyte infiltration to the damage site and promotes an adaptive immune response. Furthermore, RT can reinforce tumor cell susceptibility to T cells, enhancing their eradication and apoptosis. Cancer cell apoptosis can manifest in the form of immunogenic cell death (ICD) or non-immunogenic cell death (non-ICD). While non-immunogenic cell death fails to elicit an immune response, immunogenic cell death specializes in antitumor immunity by modifying the surface composition of the cell and releasing soluble mediators, such as danger signals, to prompt elimination of the tumor cells. With advancement in understanding of immune cell types and pathways involved in the immune response, numerous preclinical studies have suggested that a combination of radiation and immunotherapy could lead to a propitious strategy against the challenges of cancer treatment. This paper examines the remedial adjustment of tumor immune responses and how it synchronizes efficiency and resilience to RT as well as its immunologic consequences.

Introduction

The immune system both inhibits and promotes cancer development. Immune cells have the ability to act as suppressors or promoters of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Specifically, innate and adaptive immune cells within the tumor microenvironment interact with the distinct tumor through direct contact or chemokine and cytokine signaling to modify its behavior and response to therapeutic approaches [1]. The immune response to tumors is extraordinarily similar to the immune response to normal infections and foreign antigens. First, the innate immune cells that react to the damaged tissues initiate an inflammatory cascade that stimulates the adaptive immune response. Then, the activated effector T cells advance towards the tumor to eradicate it from the body. However, certain cancer cells are capable of establishing a microenvironment that protects them from anti-tumor immune responses, eventually evolving into metastatic cancer [2]. Under certain selective pressure, they can also develop a series of immune resistance mechanisms to withstand immune destruction, a process known as immunoediting [3].

Immunoediting consists of three phases that activate the innate and adaptive immune mechanisms: elimination, equilibrium, and escape. In this process, the immune system protects itself against cancer development and shapes the properties of the emanate tumors [4]. Primarily, it attempts to decimate the cancerous cells in the elimination phase. If the various attacker cells are ineffective, the immune system then reaches the equilibrium phase in which the immune cells have control over cancer but are incapable of removing the cancerous growth completely. Furthermore, the perpetual constraint of the immune system can promote genetic modifications in cancer cells, leading to additional immune resistance. This event eventually stimulates the escape phase in which the cancer cells progress and undermine the effects of the immune system [5]. As a result of this tumor cell resistance technique, advancements in radiation therapy have become more extensively adapted to combat the further proliferation of cancer cells.

Radiation therapy plays an important role in treating both localized and metastatic diseases [6]. Excited charged particles within atoms induce a series of actions leading to an ultimate biological outcome [7]. It has a wide range of cytotoxic anti-tumor effects that instigate substantial changes in apoptosis, cancer cell proliferation, morphology, and ultimately resulting in tumor shrinkage. Specifically, it induces irreversible breakage in the strands of DNA, prompting mitotic failure and eventually provoking cellular senescence and apoptosis [8]. Cells respond to DNA damage by a mechanism known as the DNA damage response (DDR), in which it activates checkpoint signaling and DNA repair pathways to stimulate cell survival [9].

The role of radiation as an immune catalyst has been increasingly acknowledged, and fields of investigation centering on integrating radiotherapy in immune-based therapies are constantly evolving. These therapeutic methods have produced promising outcomes and have significantly furthered advancements in the understanding of the interplay between effectors, tumor microenvironment, and antigen-presenting cells [10]. Radiation therapy represents one of the most substantial therapeutic approaches in combating cancer. High precision techniques are currently available and are constantly being researched to deliver a safer and more effective treatment while sparing vicinal normal tissue [8].

Immune cell response to cancer developmentRegulated by cytotoxic innate immune cells and adaptive immune cells, tumor growth originates from neoplastic tissue. During the neoplastic process, effector T cells, NK cells and macrophages from immunosurveillance components of the innate immune system help induce cancer cell apoptosis [11]. The expression of tumor antigens leads to mediation of recognition by host CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and activation of tumor-specific T cells, effectively producing the antitumor immune response [12]. Nonetheless, the development of cancer cells continues to evade immunological responses depending on the tumor microenvironment [13]. Because highly immunogenic tumor cells are eradicated in earlier stages of cancer development, immunogenic tumor cells causing an inferior immune response are selected for proliferation. As a result, the proliferated inferior immunogenic tumor cells become essentially imperceptible to the immune system [14]. Generally, antitumor immune responses are circumvented by two major groups of metastases identified through gene expression profiling: the prevention of cancer development detectability through dominant inhibition by immunosuppressive pathways or immune system exclusion [15]. The former involves a T cell–inflamed phenotype, including broad chemokine expression, T cell markers, and a type I interferon (IFNs) signature, while the latter has a non-T cell-inflamed phenotype [16].

Figure 1: Immune cells play both pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic roles in the immune system. Cells can either promote cancer growth, development, and metastasis or release cytotoxic proteins and produce immune boosting effects on the tumor microenvironment.

Tumors with the T cell-inflamed phenotype, in part caused by their CD8 α+ dendritic cell lineage, exhibit active chemokine expression which promotes the release of cytotoxic cytokines through CD8+ effector T cells. However, the effector T cells are inhibited by the immunosuppressive mechanisms programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) [15]. Treg cells have anti-tumorigenic properties including the ability to maintain homeostasis and reduce chronic inflammation but also have pro-tumorigenic properties, suppressing anticancer immune responses and stimulating inflammatory cytokine production as shown in Figure 1 [17]. These immunosuppressive mechanisms have shown to be induced by interferon-γ, and the production of CD8+ effector T cells is induced by CCR4-binding chemokines [18]. In addition, tumors with the T cell-inflamed phenotype have a tendency to also bear traditional T cells with a dysfunctional anergic phenotype, in which the lymphocyte is rendered in an inactive, unresponsive state for a period of time [19].

Within non-T cell-inflamed phenotypes, weak chemokine expression and limited T-cell infiltration contribute to tumor development, despite the lack of dominant immune inhibitory pathways [16]. Although the non-inflamed phenotype is lacking in immunosuppressive mechanisms compared to the inflamed phenotype, the presence of blood vessels, fibroblasts, and macrophages along with dense stroma continue to aid cancer cell growth [20]. In a similar fashion to CD8+ effector T cells, macrophage immune cells have both anti-tumorigenic and pro-tumorigenic effects, assisting the release of cytotoxic cytokines and antigen presentation to T cells while also promoting angiogenesis, the rapid proliferation of tumor cells, chemotaxis, and metastasis (Figure 1) [16,21].

Cancer immunoeditingThrough the activation of the innate and adaptive immune system, cancer immunoediting and the phases of elimination, equilibrium, and escape provide the foundations of novel cancer immunotherapy and radiotherapy. The basis for immunoediting relies on the presentation of antigens to T cells, as it is the propulsive force behind tumor cell apoptosis [22].

During the elimination phase, after traditional tumor suppressing mechanisms such as p53 and ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutation) have failed, tumor cells release tumor antigens such as cell-surface calreticulin as MHC I molecules and NKG2D ligands for CD8+ T and NK cell recognition [23]. Effector cells stimulate the release of IFN-γ, preventing further cancer cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Apoptosis is induced as effector T cell proliferation, IFN-α/β/γ release, and granzyme expression increases [24]. The balance between anti-tumor immunity and tumor immunity shifts towards anti-tumor immunity.

When unable to eliminate all cancerous cells, the tumor microenvironment enters the equilibrium stage in which tumor growth is controlled by the immune system and placed in an inactive state [25]. The adaptive immune system causes changes to tumor epigenicity, as cells attempt to avoid detection by the immunosurveillance mechanisms by inducing antigen loss or errors in antigen presentation and secreting immunosuppressants such as the programmed death-ligand (PDL1) [26]. PDL1 prevents immune cells from attacking harmless host cells. In tumors, an excess of PDL1 decreases immunogenicity, escaping immunological responses [27]. The balance is shifted from anti-tumor immunity towards tumor immunity due to pressure from the adaptive immune system; as a result this phase is referred to as equilibrium in which the balance between tumor promoting interleukins (IL-10, IL-23) and anti-tumor promoting interleukins (IL-12, IFN-γ) is virtually equal [26].

Tumor cells exponentially proliferate during the escape phase, as the adaptive immune system is no longer able to constrain tumor development. As a result of differentiated tumor immunogenicity and loss of antigens, tumor cells escape identification by the immune system [28]. Molecules assisting apoptosis and metastasis are secreted, including anti-apoptotic bcl-2, a pathway that can either induce or inhibit cell apoptosis through pore formation in the mitochondrial membrane and signal transduction release of cytochrome c, indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), and PD-L1 [29,30]. The secretion of cytokines VEGF, TGF-β, and IL-6 further drives the tumor microenvironment to shift out of equilibrium towards rapid tumor cell proliferation [26].

Effects of radiotherapy on the development of the immune tumor microenvironment

The tumor constructs the tumor microenvironment (TME), which is subjugated by tumor-induced interactions. It encompasses the tumor stroma, blood vessels, rapidly dividing tumor cells, inflammatory infiltrates, and an array of tissue cells associated with the tumor. The tumor itself is capable of escaping from the host immune system and modifying the functions of infiltrating cells to create an advantageous microenvironment for tumor progression [31]. Many immunosuppressive mechanisms facilitate immune escape and contribute to the growth and proliferation of the tumor, including downregulation of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), the presence of inhibitory immune cells, and enhancement of tumor vasculature barrier [32]. In general, the immune system is still able to recognize specific tumors and generate an immune response accordingly.

The involvement of therapeutic approaches, such as RT, can aid in a more effective response in cancer control (Figure 2). Under certain constraints, the addition of RT can reprogram the anti-immunogenic tumor microenvironment to make it more favorable for antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and T cells to engage and function, ultimately promoting the immune system to eradicate the tumors with increased efficiency [32]. Furthermore, the influence of RT has numerous binary effects on the host immune system contributing to pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumor outcomes. RT alters the TME by cytokines and chemokines secretion, effectively increasing infiltration by leukocytes and amplifying the sensitivity of tumor cells to immune-mediated tumor rejection [33].

Figure 2: Tumor microenvironment with the addition of radiation. RT promotes immunogenic cell death of tumor cells, induces cytokines and chemokines, increases the infiltration of leukocytes, and promotes cross-presentation of tumor antigens. This contributes to the eradication of the tumor and s

Radiation-induced cytokine and chemokine secretion

The radiation-induced outburst of cytokines and chemokines causes inflammation in the tumor microenvironment predominantly to expel foreign antigens from disrupting tissue homeostasis. These molecules are messengers that allow the cells within the immune system to communicate with each other to initiate a synchronized, vigorous response to suppress microbial pathogens [34]. In some cases, they may also induce cell transformation and malignancy depending on the tumor microenvironment and balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines [35]. Radiation-induced interferons (IFNs) are the central effector molecules of the antitumor immune response. In the tumor system, the functions of type I IFNs are vaguely distinguished; however, evidence proposes that they may contribute to controlling tumor growth. Particularly, a study employing an IFN-α/β neutralizing anti-serum revealed that the cytokine may limit the development of transplantable tumors. The deprivation of type I IFN signaling stemmed a more expeditious tumor growth and heightened mortality in multiple tumor prototypes [36]. These effector molecules are critical for the activation and function of Dendritic cells (DCs) and T cells that are responsible for the distribution of IFN-γ and tumor management [32]. IFN-γ is a type II IFN that upregulates the expression of VCAM- 1 and MHC-I to emphasize tumor antigen presentations. Hence, radiation-induced interferons are a type of cytokine that plays a substantial role in creating a tumor microenvironment that is propitious for T cell infiltration and tumor cell target recognition [37].

In contrast, the transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ), also activated by RT, is the major immunosuppressive factor that hinders the immune response [38]. This pleiotropic cytokine is responsible for numerous cell functions including apoptosis, differentiation, proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and migration [39]. Although it may normally enforce tissue homeostasis and prevent developing tumors from progressing towards malignancy, cancer cells are capable of availing TGFβ to their benefit to commence immune evasion, growth factor production, and expand metastatic colonies if they lose TGFβ tumor-suppressive responses. Essentially, TGFβ is the key enforcer in immune tolerance; tumors that produce elevated levels of this cytokine are protected against immune surveillance, a process in which the immune system identifies cancerous cells and eradicates them before they inflict any harm [40]. TGFβ can suppress the immune response in the tumor microenvironment by inhibiting the proliferation of T-cells and reducing the antigen-presenting ability of DCs [41]. Generally, these pro-tumoral and antitumoral roles of these various cytokines, induced by RT, primarily depend on the balance of the different inflammatory mediators and stage of tumor development [35].

Radiation-induced leukocyte infiltrationThe inflammatory cytokines and chemokines induced by radiation not only intensify tumor infiltration by leukocytes and natural killer cells that augment anti-tumor immune responses, but also immunosuppressive cells such as regulatory T cells (Treg cells) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [32]. The net balance between pro-tumorigenic signals and anti-tumorigenic signals along with the function of radiation-induced chemokines determine the infiltrating leukocyte cells’ composition and the final effectiveness of tumor control. For example, RT-induced chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand 9 (CXCL9), -10 and -16 productions stimulate antitumor T cells and amplify tumor control; in contrast, secretion of CXCL12 and colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) can prompt tumorpromoting CD11b+ myeloid cells [8] to trigger tumor angiogenesis and accelerate tumor metastasis. These inflammatory cells are part of the immune response whose aim is to invade tumors, slowing their progression. Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs) are the primary component of immune infiltrates in tumors. However, the antigens released in the tumor microenvironment affect them substantially; they cause diminished lymphocyte proliferation and T cell receptors signaling as well as a reduced ability to mediate the cytotoxicity of tumor targets. This immunosuppressive mechanism on these lymphocytes helps the tumor escape immune destruction [39]. The influence of RT is capable of inducing DCs’ maturation and facilitating their movement from the tumor site to the draining lymph nodes [42]. They are critical in tumor antigen presentation and in the development and maintenance of T cells and their successive tumor infiltration [43]. In addition, radiation can amplify NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity to extirpate tumor cells by increasing the expression of tumor ligands for NK cell-activating receptors [32].

A significant immunosuppressive mechanism stimulated by the radiation-induced release of inflammatory cytokines is Tregs. Tregs are a type of potent T cells that are able to proliferate in the tumor microenvironment and generate excessive interleukins 10 (IL-10) and TGFβ [44]. Interleukins contribute to tumor escape from immune surveillance by stimulating cell growth and inhibiting cell apoptosis. The behaviors of the IL-10 and TGFβ cytokines are complementary and prone to induce a positive feedback loop where one amplifies the expression of the other [45]. Furthermore, elevated levels of Tregs can also obstruct the functions of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), an anti-tumor effector cell, by impeding their ability to signal for the destruction of tumor cells. Macrophages, an essential leukocyte to immunal responses, have a dual effect while infiltrating the tumor microenvironment. They can either organize into tumor resisting M1 or tumor- promoting M2 macrophages. Studies have indicated that TAMs are similar to M2- type macrophages, correlating with tumor invasion and metastasis. TAMs also secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGFβ to impede the functions of effector T cells and regulate tumor progression [46].

Radiation-induced tumor cell susceptibilityRT promotes T-cell and NK-cell-mediated lysis of tumor cells by MHC-I and NK cell ligand regulation. Internal peptides are presented using MHC class II molecules to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Many studies have observed the association between the upregulation of MHC-I molecules as a result of radiotherapy induction and the intensified lysis of irradiated tumor cells by tumor antigen-specific T cells [8]. Increasing the expression of MHC-I causes an increase in the presentation of tumor antigens and renders tumor cells to be more susceptible to T cell attack [47]. More specifically, the exposure to RT increases peptides for antigen presentation exhibited by MHC-I molecules. Subsequently, tumor-associated derived antigens (TAAs) are able to be seized by DCs; The DCs use Toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognition to become active and recognize danger signals emitted by dying tumor cells. They eventually migrate to the secondary lymphoid organs to present the TAAs to the CD4+ T cells, assisting in the eradication of tumor cells [48]. CD4+ T cells can directly eradicate distinct tumor cells expressing MHC-II molecules or indirectly eliminate the ones lacking MHC-II expression. Additionally, CD4+ T cells are also capable of improving the efficiency of CD8+ T cells in identifying tumor peptides by MHC-I [49].

Another essential mechanism induced by RT is the expression of Fas and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM)-1 on tumor cells. Enhanced Fas expression leads to a more efficient CTL killing and improved antitumor activities. This generally influences the tumor cells to be more receptive to T cell-mediated lysis [50]. ICAM- 1 is located on the surface of T cells and is predicted to engage in signal transductions which contributes to controlling activation, proliferation, cytotoxicity and cytokine production of cells. Overall, studies have shown that regulating the MHC-I molecules and the expression of Fas and ICAM-1 through radiation can significantly improve therapeutic efficiency in inhibiting tumor growth [51].

Radiation-mediated immunogenic cell death

Immunogenic cell death (ICD) is a specific type of apoptosis that releases soluble mediators such as immunogenic damageassociated molecular patterns (DAMPS) and involves cell surface composition alterations [52]. DAMPS function as danger signals and have the ability to enhance the immunogenicity of dying cells [53]. After exposure to radiation, major DAMPs such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), non-histone chromatin-binding protein high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and calreticulin (CRT) mediate effective ICD. This distinct mode of cell death transmits danger signals to prompt tumor antigen presentation and subsequent T cell priming, crucial to eliciting tumor rejection and impeding distant dispersal [8]. Each danger signal binds to a specific receptor on the surface of dendritic cells and induces phagocytosis of dying cells as well as antigen processing and presentation. This event eventually leads to an antitumor response via the recruitment and activation of various T cells, shown in figure 3 [54].

Figure 3: After the manifestation of radiation, DAMPS, such as exposure of ER chaperone calreticulin on the cell surface (ecto-CRT), secretion of ATP, and release of HMGB1. These DAMPs bind to specific receptors on the surface of dendritic cells (DC) and induce engulfment of dying cells, tumor antigen processing and presentation. This mechanism of DC maturation and activation leads to an anti-tumor response through recruitment and activation of natural killer cells, CD4+, and CD8+ cells.

ICD results in the translocation of CRT to the cell surface; CRT acts as a DC “eat-me” signal and instigates phagocytosis and the subsequent tumor antigen presentation to T cells. The CRT protein makes up a large portion of the molecules in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and shifts towards the surface only when the ER stress response is involved. Specifically, this stress entails the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) to undergo phosphorylation [55]. Next, the extracellular release of HMGB1 mediates responses to inflammation and injury by acting as a cytokine when dispersed from dying cells. HMGB1 is a protein expressed in almost all cells with an intact nucleus; HMGB1 has an important role in regulating DNA associated events consisting of DNA repair and genome stability [56,57]. Furthermore, HMGB1 expression outside of the nucleus is involved with cell proliferation, inflammation, immunity, and autophagy [57]. HMGB1 specifically interacts with toll-like receptors-4 (TLR4) on dendritic cells, triggering them to present tumor-associated antigens [58]. Lastly, the release of ATP acts as a “danger” signal that triggers DCs and other antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to the tumor site and promotes pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 to be secreted [42]. It acts on the P2XR7 purinergic receptors of immune cells to allow the secretion of cytokines [54]. Antigen presenting cells that respond to ICD can then instigate other immune cells that are capable of attacking the remaining tumor cells [59].

In addition to the immunostimulant effects of DAMPs, they also elicit an immunosuppressive effect. In contrast, to the CRT’s “eat me” signal, the CD47 protein encodes the DC “do-not-eat-me” signal expressed in solid tumor cells; its blockage is associated with tumor rejection mediated by the immune system. However, exposure to radiation therapy can effectively reduce the amount of CD47 expression in the tumor cells [56]. ATP, a critical effector in ICD, also displays a dual effect, both acting as a chemotaxis initiator and activator of the inflammatory pathway, dependent on extracellular ATP concentration. Excess extracellular ATP can be converted into adenosine to react with certain receptors, often resulting in immunosuppressive effects to enhance tumor progression. In addition, the instigation of A2A receptors promotes metastasis by decreasing the maturation and cytotoxic functions of NK cells. Studies have also shown A1 and A3 receptors may also enhance tumor proliferation [60]. HMGB1 interacting with various receptors can exert immunosuppressive cell regulating effects. One example, the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE), has been displayed in multiple studies as a critical cell surface receptor for HMGB1. Experimental data shows that upon interaction, HMGB1 and RAGE can activate various signaling pathways such as NF-кB, MAPKs, or SrcK to induce tumor cell invasion and metastasis [61]. In pancreatic tumor cells, targeted prostate RAGE prompts increased apoptosis, decreased tumor cell survival and reduced autophagy. Predominantly, these specific DAMPs exhibit a dual and paradoxical role in preventing and developing cancer. Understanding the distinct mechanisms that trigger the tumorigenic effects is critical for the development of future treatments [62].

cGAS-STING pathway activation by radiationViral mimicry occurs when cytosolic DNA accrues in tumor cells exposed to ionizing radiation and acts as the catalyst for T cell activation by radiation [63]. Once in a viral mimicry state, the anti-tumoral effect is produced, in which the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway is activated [64]. Consequently, this leads to induction of type III IFNs and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), a reduction in tumor cell proliferation, and targeting of cancer-initiating cells (CICs) [65]. The cGAS-STING pathway is an essential defense instrument used in DNA-sensing mechanisms in order to boost the innate immune system and combat viral diseases.

Studies have shown the cGAS-STING pathway to have immunosurveillance purposes, able to function as both a tumor suppressant by increasing antitumor immunity [66]. cGAS and STING pathways, however, may also act as immunosuppressants, decreasing weakening immune defenses in the TME and promoting cancer metastasis [67]. cGAS identifies pathogenic foreign DNA as well as leaked host DNA as a result of cellular and genome damage while STING triggers the release of inflammatory cytokines [68]. In addition to DAMPS, the innate immune system also activates immune cells in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS). DAMPS and PAMPS are both forms of danger signals able to bind to and be recognized by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), allowing the initiation of the immune response [69]. PRRs can be divided into categories of membrane-bound receptors or cytosolic receptors, consisting of toll-like receptors (TLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–like receptors (NLRs), respectively [70]. cGAS is a cytosolic PRR activated through DNA binding, thus initiating a signal transduction cascade exhibited by the formation of a cGAS2-DNA2 complex and conformational change in cGAS [71]. At the binding site, 2′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) is formed through ATP and GTP conversion.. cGAMP binds to STING in the endoplasmic reticulum. STING subsequently mediates the phosphorylation of interferon Regulatory Factor 3 (IRF3) by TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), both proteins central to the innate immune response. This phosphorylation triggers the binding of type I IFNs to type I IFN receptors, activating the transcription and expression of ISGs [72]. Furthermore, STING signals regulatory protein IKKβ for expression of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) for purposes of proinflammatory cytokine production [73]. Lastly, STING is degraded by cellular lysosomes and autophagic molecules while cGAMP accumulates in tumor cells through replication [72]. As a result, defensive immune mechanisms are activated against cancerous growth, priming CD8+ T cells with anti-tumorigenic properties. The abscopal effect occurs in response and creates tumor suppression both within and distant to the irradiated area [72,74].

Inflammasome recognition of DNA damageInflammasomes are a class of multi-protein intracellular oligomers belonging to the innate immune system whose function is to initiate inflammatory reactions [75]. Common inflammasomes include nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs), the adaptor protein (ASC), and pro-caspase-1 [76]. In response to high-dose radiation, innate immune signal pathways are stimulated by radiation DNA damage [77]. Ionizing radiation causes initiation of endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways, activating epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) in the plasma membrane. The damaged DNA is then recognized by Absent in Melanoma 2 (AIM2) and NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes and consequently, induction of pyroptosis and apoptosis occurs [78]. While apoptosis is simply the process of programmed cell death, pyroptosis is a form of highly inflammatory cell death, specifically dependent on the enzyme caspase-1 [79].

AIM2 acts as a cytoplasmic dsDNA sensor, able to recognize viral dsDNA, deviant host DNA, and bacterial DNA [80]. When activated through binding to cytosolic double-stranded DNA in macrophages at the AIM2 C-terminal HIN-200 domain, the PYDdomain interacts with ASC [81]. In this way, the AIM2 inflammasome is assembled: ASC signals pro-caspase-1 to bind to the multi-protein complex already consisting of CARD9, Malt1, Bcl-10, and caspase-8, successfully releasing proinflammatory cytokines and prompting proinflammatory pyroptosis using caspase-1 [82,83]. Caspase-1 triggers the secretion of interleukins during this process in which gasdermin 9 (GSDMD) is cleaved. The formation of GSDMD-p30 pores occurs on macrophages as a result allowing the release of interleukins-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 [83,84]. The assembly of inflammasomes AIM2 and AIM2 is often present in individuals with early-stage acute pancreatitis, prostatic diseases, and prostate cancer [83].

NLRP1, NLRP2, NLRP3, NLRP4, NLRP6, NLRP12, NLRP14 and NLRC4 are all inflammasome subsets of the NLR protein active in the innate immune system. All such inflammasomes have the ability of self-oligomerization due to their NOD domains [83]. NLR classes of inflammasomes also include C-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) used for ligand-recognition for receptors such as TLR and other ligands [85]. NLRP3 inflammasome is activated through two waves of signalling: TLR/nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway signalling and subsequently PAMP and DAMP signalling [86]. The TLR/nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway causes upregulation of NLRP3 and IL-1β, (precursor IL-1β), and IL-18 (precursor IL-18), as well as primes the inflammasome for assembly. In other cases, reactive oxygen species (ROS) uses TLR4/MyD88 signal pathways to prime NLRP3 inflammasomes [83]. Similar to AIM2, ASC and pro-caspase-1 join together to form a multi-protein complex in the second wave of PAMP/DAMP signalling. Pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 are cleaved, transitioning to their completed final forms IL-1β and IL-18, and inflammasome assembly is finalized [87]. NLRP3 inflammasomes are most commonly expressed in cancer of the cranial regions, colorectal cancer, and oral squamous carcinoma, having the ability to promote inflammatory tumor growth and tumor metastases [83].

The Abscopal Effect and Bystander Effect

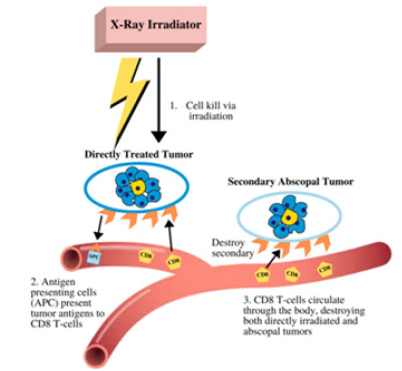

The abscopal effect is produced when localized radiation induces systemic antitumor effects distant from the focal site [88]. Conversely, the bystander effect refers to the apoptosis of nonirradiated cells at the focal site. These effects contribute to reducing tumor growth outside the radiation field by helping prevent further metastases and are relatively mediated by the immune system [89]. The true mechanism by which the abscopal and bystander effect manifests requires further study, as it is currently unknown. However, it is widely accepted to be involved with the immune response system as well as intercellular signaling and intracellular communication through gap junctions [90]. The proposed mechanism begins with tumor exposure to ionizing radiation, causing the release of tumor antigens by the irradiated tumor cells. Once tumor antigens interact with the antigen-presenting cells (APCs), CD8+ T cells are prompted to propagate out of the lymph nodes towards the primary tumors, directly lysing cancer cells and releasing cytotoxic cytokines. CD8+ T cells then circulate throughout the body traveling within lymph nodes and proceed to eradicate non-irradiated tumor metastases as shown in Figure 3 [12].

Many clinical experiments have shown that the abscopal effects in RT alone are very infrequent because of the counterbalance of the pro-immunogenic signals induced with the immunosuppressive effects [88]. Radiotherapy is restricted by normal tissue toxicity and is predominantly used for treating localized tumors [91]. This has influenced scientists to stem research in combining radiation therapy with immunotherapy techniques to improve the effectiveness of treatments [92]. One of the earliest identifications of the bystander effect was observed in Chinese hamster ovary cells exposed to 0.31mGy 238Pl α-particle radiation. 30% of ovary cells exhibited induction of sister chromatid exchanges. However, only 1% of ovary cells were traversed by an alpha particle, indicating that low dosage radiation may have the ability to induce genetic modifications in tumor cells not exposed to radiation [93]. Similarly, other studies have shown analogous results: in human T98G glioblastoma cells were irradiated using a single cell microbeam with an exact measure of helium ions. 1% of cell nuclei were targeted, yet 40% of the cells exhibited increased levels of nitric oxide (NO). The addition of 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)- 4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (c-PTIO), a nitric oxide scavenger, caused cellular damage to reduce to normal levels, suggesting NO is involved with the bystander effect [94]. Even more studies have demonstrated cell-derived soluble factors such as cytokines IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, TGF-β1, TNF-α, transcription factor NF- κB, and DNA damage repair ATM protein, to influence the bystander effect [78,95].

A crucial basis for the presence of the abscopal effect was identified in a 2015 clinical trial in which patients had metastatic solid tumors. Subjects were treated with 35Gy/10fx radiotherapy applied to one metastatic site and injected subcutaneously with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors (125μg/ m^2) daily for two weeks. 11 subjects out of the 41 in the study experienced abscopal effects [96]. Abscopal effects were also found in cancers ranging in areas such as the chest, breast, pancreas, head, neck, colon, and lung, suggesting such effects are significant in regard to establishing future in-situ cancer immunity [96,97]. Further experimentation has shown inflammatory regulators such as cytokines and DAMPS activate dendritic cells, macrophages, and cytotoxic .0T lymphocytes, contributing to development of the antitumorigenic immune response [78].

Combining radiation with immunotherapyCombinations of radiation and immunotherapy can enhance the possibility of systemic anti-tumor immunity. RT acts as a supplement to fortify the immune response resulting in neutralization of the immunosuppressive effects of the tumor microenvironment. Immunotherapy aims to inhibit the immune escape of cancer and negate immune rejection in a complementary manner [98]. Different preclinical studies combining immunotherapy and radiotherapy continuously exhibit substantial improvement in the abscopal response rate compared to independent usage of either one of the therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, the variety of immunotherapeutic agents have the ability to target different aspects of the immune-mediated response. For example, an anti- CD40 antibody can be implemented to amplify the activation of APCs, and immune checkpoint inhibitors can increase T cell activity [78].

Currently, checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) are the one of the most commonly used methods of immunotherapy and have presented notable results in preclinical studies. Inhibitors targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) have had considerable positive benefits in regards to patient care as well as an extensive range of late-stage malignant tumors. The effects of combining radiotherapy and CPI involve an elaborate interplay with the adaptive and innate immune systems [99]. Research on RT has demonstrated that in RT-resistant tumors that overexpress checkpoint molecules as feedback to RT, therapeutic responses are amplified by CPI [100]. Specifically, after continual exposure to antigens, T cell checkpoints (CTLA-4, PD-1), cell surface molecules, inhibit T cell activation. Impeding these checkpoints enhances the anti-tumor T cell activity, creating an immunostimulant response [101]. Similarly, in a different research study in an MC38 cell line model of colon cancer, RT exposure with PD-L1 blockage substantially reduced tumor growth. Further improvements in survival were exhibited when a dual checkpoint blockade of both anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 was implemented along with RT [100].

However, with the vast number of cancers, some patients do not respond to immune checkpoint inhibition using blocking antibodies to CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1. Thus, different immunotherapeutic strategies are being examined. Understanding the mechanisms involved in innate and adaptive immunity is a key principle in successful cancer immunotherapy [102]. CD40 is a component of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors expressed on various APCs and tumor cells. Clinical trials associated with antibodies against CD40 have been revealed to suppress tumor growth. For example, in DCs, anti-CD40 amplifies cell-surface expression of MHC molecules and instigates proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in enhanced lymphocyte activation. In addition, on tumorassociated macrophages, anti-CD40 treatment prompts phenotype change from M2 to M1 type, influencing the induction of cytotoxic T-cell and NK-cell responses against tumors [103]. Overall, the development of new immunotherapies and further enhance the immune response, especially with the abscopal effect (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The proposed mechanism of the abscopal effect. Local radiation causes tumor cell death generating an adaptive immune response, generating anti-tumor effects to the directly treated tumor cells as well as secondary tumors distant from the treatment site.

Immune response variation as a consequence of radiation dose delivery

The inflammatory immune response is dependent on many factors of RT and ionizing radiation, including radiation type, dose, energy, fractionation, field size, RT delivery, and time of delivery [74]. For example, types of radiation may be categorized as α-particle, β-particle, γ-particle, x-ray, proton, neutron, or heavy ion. RT dose rates, α/β ratio, and mode of delivery (e.g. brachytherapy, external beam, and radioembolization) all vary in how they modulate the tumor microenvironment and immune system [78].

The standard dose fractionation of delivered radiation is commonly 2Gy [74,104]. In in vivo studies, the usage of larger doses have resulted in improved pro-immunogenic tumor effects, so theoretically similar results should manifest in in vitro studies, yet in vitro studies suggest the relationship between RT and the tumor microenvironment is more intricate than previously expected [74]. Larger dosages such as 30Gy compared to the conventional 2Gy dosage and hypofractionated dosages ranging from 6Gy to 8Gy have exhibited effects no more significant than their counterparts [105].

In a 2018 study, mice were exposed to thoracic ionizing radiation using X-ray delivery at either 15Gy with a dose rate of 1.8Gy/min or 20Gy Flash RT with a dose rate of greater than 2400Gy/min. Both treatments resulted in similar anti-tumor immune responses. However, Flash RT produced less fibrotic lesions [106]. Other preclinical studies suggest higher single dosage RT promotes antitumorigenic immune cells by increasing the amount of CD8+ T cells through the cross-priming of antigen-specific dendritic cells [107]. One study applied 10 Gy Flash RT at a dose rate of greater than 1600 Gy/min compared to traditional RT hypofractionated dosage at 6Gy/min to the murine cranial region. Subsequently, it was discovered that conventional RT resulted in worsened neurogenesis capabilities, memory, and hippocampal function compared to Flash RT [108]. α/β ratio radiosensitivity produces noticeable differences in cell line immune response, as a larger α/β ratio has led to considerable preclinical results [109,110]. Ultimately, the variance of dosage rates, fractionation, and RT delivery method requires extensive examination in regard to biological effectiveness in order for application to future clinical settings.

Conclusion

There is significant evidence supporting the benefits of incorporating radiation as a therapeutic approach to combat the progression of cancer. RT is known for its ability to eradicate and reprogram tumor cells, causing a number of immunogenic consequences during immune system exposure. The immune system has a substantial role in averting and promoting the development of cancer. More specifically, the innate and adaptive immune cells within the tumor microenvironment can directly interact with the tumors by secretion of chemokines and cytokines in response to tumor development. Radiation can alter the surroundings to produce a more favorable medium for APCs and T cells to engage and function, consequently promoting the immune system to eradicate tumors more efficiently within the tumor microenvironment. As a result, the release of cytokines and chemokines creates an environment propitious for T cell infiltration and tumor recognition. These molecules also increase tumor cell susceptibility to leukocyte infiltration, augmenting the anti-tumor response. Radiation further enhances the tumor cells weakness to T cells and NK-cell-mediated lysis to improve antitumor activities. The expression of Fas and ICAM-1 enhances CTL-killing activities and improves therapeutic efficiency in inhibiting tumor growth. cGAS-STING pathway activation and viral mimicry of tumor cells is stimulated by radiation to prime CD8+ T cells with anti-tumorigenic properties. Radiation influences ICD, a significant form of apoptosis involving DAMPS such as ATP, HMG1, and CRT as danger signals to prompt tumor antigen presentation and subsequent T cell priming for tumor rejection.

In addition to these anti-tumor responses, there are protumorigenic consequences to the exposure of radiation. Cytokines and chemokines such as TGFβ and CXCL12 generate an immunosuppressive effect to aid in tumor escape by diminishing lymphocyte proliferation, inhibiting T cell signaling, and reducing APC abilities. Inflammasome recognition of DNA damage plays a diverse role in interleukin induction, functioning to either promote or inhibit cancer development. Distinct Treg cells obstruct the functions of CTLs. For DAMPS, these danger signals may elicit protumor effects to enhance tumor growth by excess ATP secretion or altering the receptors for HMGB1. Lastly, the abscopal effect is a critical mechanism in diminishing the effects of tumor proliferation; abscopal and bystander effects reduce tumor growth both distant and focal to the radiation field to create a more efficient response. Unfortunately, this phenomenon occurs infrequently in radiation alone due to the counterbalance of pro-immunogenic signals induced with the immunosuppressive effect. Combinations of radiation and immunotherapy methods as well as radiation dose delivery methods require further exploration to improve treatment effectiveness. Ultimately, investigation of the effects of RT on the immune system has led to the discovery of new information, allowing future treatments to become more extensively adapted to combat the further proliferation of cancer cells.

Disclosure

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Markman JL, Shiao SL (2015) Impact of the immune system and immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology 6(2): 208-223.

- Pandya PH, Murray ME, Pollok KE, Renbarger JL (2016) The immune system in cancer pathogenesis: Potential therapeutic approaches. Journal of Immunology Research 4273943.

- Liu Y, Dong Y, Kong L, Shi F, Zhu H, et al. (2018) Abscopal effect of radiotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 11(1): 104.

- Mittal D, Gubin MM, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ (2014) New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases elimination, equilibrium and escape. Current Opinion in Immunology 27: 16-25.

- Strausberg RL (2005) Tumor microenvironments, the immune system and cancer survival. Genome Biology 6(3): 211.

- Sridharan V, Schoenfeld JD (2015) Immune effects of targeted radiation therapy for cancer. Discov Med 19(104): 219-228.

- Carvalho HA, Villar RC (2018) Radiotherapy and immune response: the systemic effects of a local treatment. Clinics (São Paulo) 73(Suppl 1): e557s.

- Walle T, Martinez Monge R, Cerwenka A, Ajona D, Melero I, et al. (2018) Radiation effects on antitumor immune responses: Current perspectives and challenges. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology 10: 1758834017742575.

- Jackson SP, Bartek J (2009) The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature 461(7267): 1071-1078.

- Roses RE, Datta J, Czerniecki BJ (2014) Radiation as immunomodulator: Implications for dendritic cell-based immunotherapy. Radiation Research 182(2): 211-218.

- Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z (2018) Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes & Development: 32(19-20): 1267-1284.

- Ostroumov D, Fekete-Drimusz N, Saborowski M, Kühnel F, Woller N (2018) CD4 and CD8 T lymphocyte interplay in controlling tumor growth. Cellular and molecular Life Sciences : CMLS 75(4): 689-713.

- Zhou J, Wang G, Chen Y, Wang H, Hua Y, et al. (2019) Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy: Present and emerging inducers. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 23(8): 4854-4865.

- Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z (2018) Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes & Development 32(19-20): 1267-1284.

- Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX (2013) Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nature Immunology 14(10): 1014-1022.

- Gajewski TF, Corrales L, Williams J, Horton B, Sivan A, et al. (2017) Cancer immunotherapy targets based on understanding the T cell-inflamed versus non-T cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1036: 19-31.

- Markman JL, Shiao SL (2015) Impact of the immune system and immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology 6(2): 208-223.

- Qu X, Tang Y, Hua S (2018) Immunological approaches towards cancer and inflammation: A cross talk. Frontiers in Immunology 9: 563.

- Schwartz RH (2003) T cell anergy. Annu Rev Immunol 21: 305-334.

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M (2010) Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140(6): 883-899.

- Gun SY, Lee S, Sieow JL, Wong SC (2019) Targeting immune cells for cancer therapy. Redox Biology 25: 101174.

- Vesely MD, Schreiber RD (2013) Cancer immunoediting: Antigens, mechanisms, and implications to cancer immunotherapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1284:1-5.

- Morgan SE, Kastan MB (1997) p53 and ATM: cell cycle, cell death, and cancer. Adv Cancer Res 71:1-25.

- Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K (2007) Cancer immunoediting from immune surveillance to immune escape. Immunology 121(1): 1-14.

- Wang M, Zhao J, Zhang L, Wei F, Lian Y, et al. (2017) Role of tumor microenvironment in tumorigenesis. Journal of Cancer 8(5): 761-773.

- Mittal D, Gubin MM, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ (2014) New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases--elimination, equilibrium and escape. Current Opinion in Immunology 27: 16-25.

- Jiang X, Wang J, Deng X, Xiong F, Ge J, et al. (2019) Role of the tumor microenvironment in PD-L1/PD-1-mediated tumor immune escape. Molecular Cancer 18(1): 10.

- Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z (2018) Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes & Development 32(19-20): 1267-1284.

- Ye Z, Yue L, Shi J, Shao M, Wu T (2019) Role of IDO and TDO in cancers and related diseases and the therapeutic Implications. Journal of Cancer 10(12): 2771-2782.

- Zhou Y, Weyman CM, Liu H, Almasan A, Zhou A (2008) IFN-gamma induces apoptosis in HL-60 cells through decreased Bcl-2 and increased Bak expression. J Interferon Cytokine Res 28(2): 65-72.

- Whiteside TL (2008) The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene 27(45): 5904-5912.

- Liu Y, Dong Y, Kong L, Shi F, Zhu H, et al. (2018) Abscopal effect of radiotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 11(1): 104.

- Chow MT, Luster AD (2014) Chemokines in cancer. Cancer immunology research 2(12): 1125-1131.

- Lee S, Margolin K (2011) Cytokines in cancer immunotherapy. Cancers 3(4): 3856-3893.

- Landskron G, De la Fuente M, Thuwajit P, Thuwajit C, Hermoso MA (2014) Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. Journal of Immunology Research 149185.

- Burnette BC, Liang H, Lee Y, Chlewicki L, Khodarev NN, et al. (2011) The efficacy of radiotherapy relies upon induction of type i interferon-dependent innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Research 71(7): 2488-2496.

- Lugade AA, Sorensen EW, Gerber SA, Moran JP, Frelinger JG, et al. (2008) Radiation-induced IFN-γ production within the tumor microenvironment influences antitumor immunity. J Immunol 180(5): 3132-3139.

- Vanpouille-Box C, Diamond JM, Pilones KA, Zavadil J, Babb JS, et al. (2015) TGFβ is a master regulator of radiation therapy-induced antitumor immunity. Cancer Research 75(11): 2232-2242.

- Syed V (2016) TGF-β signaling in cancer. J Cell Biochem 117(6): 1279-1287.

- Swann JB, Smyth MJ (2007) Immune surveillance of tumors. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 117(5): 1137-1146.

- Wrzesiński SH, Wan YY, Flavell RA (2007) Transforming growth factor-β and the immune response: Implications for anticancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 13(18Pt 1): 5262-5270.

- Lugade AA, Moran JP, Gerber SA, Rose RC, Frelinger JG, et al. (2005) Local radiation therapy of B16 melanoma tumors increases the generation of tumor antigen-specific effector cells that traffic to the tumor. J Immunol 174(12): 7516-7523.

- Gupta A, Probst HC, Vuong V, Landshammer A, Muth S, et al. (2012) Radiotherapy promotes tumor-specific effector CD8 T cells via dendritic cell activation. J Immunol 189(2): 558-566.

- Martin M, Wei H, Lu T (2016) Targeting microenvironment in cancer therapeutics. Oncotarget 7(32): 52575-52583.

- Mocellin S, Marincola FM, Young HA (2005) Interleukin‐10 and the immune response against cancer: A counterpoint - Mocellin . Journal of Leukocyte Biology 78(5): 1043-1051.

- Räihä MR, Puolakkainen PA (2018) Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) as biomarkers for gastric cancer: A review. Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine 4(3): 156-163.

- Garrido F, Aptsiauri N, Doorduijn EM, Garcia Lora AM, van Hall T (2016) The urgent need to recover MHC class I in cancers for effective immunotherapy. Current Opinion in Immunology 39: 44-51.

- Ithaisa S, Rodríguez-Gallego, Pedro Lara (2014) Immune effects of high dose radiation treatment: Implications of ionizing radiation on the development of bystander and abscopal effects. Translstional Cancer Medicine 3(1).

- Haabeth OA, Tveita AA, Fauskanger M, Schjesvold F, Lorvik KB, et al. (2014) How do CD4(+) T cells detect and eliminate tumor cells that either lack or express mhc class ii molecules? Frontiers in Immunology 5: 174.

- Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Camphausen K, Liu K, Scott T, et al. (2003) Irradiation of tumor cells up-regulates fas and enhances CTL lytic activity and ctl adoptive immunotherapy. J Immunol 170(12): 6338-6347.

- Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Coleman CN, Camphausen K, Schlom J, Hodge JW (2004) External beam radiation of tumors alters phenotype of tumor cells to render them susceptible to vaccine-mediated T-cell killing. Cancer Res 64(12): 4328-4337.

- Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L (2013) Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol 31: 51-72.

- Li X (2018) The inducers of immunogenic cell death for tumor immunotherapy. Tumori 104(1): 1-8.

- Eppensteiner, John, Davis, Patrick R, Barbas, SA, Jaewoo (2018) Immunothrombotic activity of damage-associated molecular patterns and extracellular vesicles in secondary organ failure induced by trauma and sterile insults. Front Immunol 9: 190.

- Sukkurwala AQ, Martins I, Wang Y, Schlemmer F, Ruckenstuhl C, et al. (2014) Immunogenic calreticulin exposure occurs through a phylogenetically conserved stress pathway involving the chemokine CXCL8. Cell Death and Differentiation 21(1): 59-68.

- Golden EB, Apetoh L (2015) Radiotherapy and Immunogenic Cell Death. Semin Radiat Oncol 25(1): 11-17.

- He S, Cheng J, Sun L, Wang Y, Wang C, et al. (2018) HMGB1 released by irradiated tumor cells promotes living tumor cell proliferation via paracrine effect. Cell Death Dis 9(6): 648.

- Ladoire S, Enot D, Andre F, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G (2015) Immunogenic cell death-related biomarkers: Impact on the survival of breast cancer patients after adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncoimmunology 5(2): e1082706.

- Kumari A, Simon SS, Moody TD, Garnett-Benson C (2016) Immunomodulatory effects of radiation: What is next for cancer therapy? Future Oncology (London, England) 12(2): 239-256.

- Hernandez C, Huebner P, Schwabe RF (2016) Damage-associated molecular patterns in cancer: A double-edged sword. Oncogene 35(46): 5931-5941.

- He S, Cheng J, Feng X, Yu Y, Tian L, et al. (2017) The dual role and therapeutic potential of high-mobility group box 1 in cancer. Oncotarget 8(38): 64534-64550.

- Cebrián MJ, Bauden M, Andersson R, Holdenrieder S, Ansari D (2016) Paradoxical role of HMGB1 in pancreatic cancer: tumor suppressor or tumor promoter? Anticancer Research 36(9): 4381-4390.

- Roulois D, Loo yau H, Singhania R, Wang Y, Danesh A, et al. (2015) DNA-Demethylating agents target colorectal cancer cells by inducing viral mimicry by endogenous transcripts. Cell 162(5): 961-973.

- Lhuillier C, Rudqvist N, Elemento O, Formenti SC, Demaria S (2019) Radiation therapy and anti-tumor immunity: exposing immunogenic mutations to the immune system. Genome Med 11(1): 40.

- Pervolaraki K, Rastgoutalemi S, Albrecht D, Bormann F, Bamford C, et al. (2018) Differential induction of interferon stimulated genes between type I and type III interferons is independent of interferon receptor abundance. PLoS Pathog 14(11): e1007420.

- Kwon J, Bakhoum SF (2020) The cytosolic DNA-sensing cGAS- in sting pathway cancer. Cancer Discov 10(1): 26-39.

- Li T, Chen ZJ (2018) The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 215(5): 1287-1299.

- Hong C, Tijhuis AE, Foijer F (2019) The cGAS paradox: contrasting roles for cGAS-sting pathway in chromosomal instability. Cells 8(10): 1228.

- Amarante-mendes GP, Adjemian S, Branco LM, Zanetti LC, Weinlich R, et al. (2018) Pattern recognition receptors and the host cell death molecular machinery. Front Immunol 9: 2379.

- Kawai T, Akira S (2009) The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. International Immunology 21(4): 317-337.

- Bai J, Liu F (2019) The cGAS-cGAMP-sting pathway: A molecular link between immunity and metabolism. Diabetes 68(6): 1099-1108.

- Yum S, Minghao L, Frankel A, Zhijian C (2019) Roles of the cGAS-sting pathway in cancer immunosurveillance and immunotherapy. Annual Review of Cancer Biology 3: 323-344.

- Pfeffer LM (2011) The role of nuclear factor κB in the interferon response. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research 1(7): 553-559.

- Carvalho HA, Villar RC (2018) Radiotherapy and immune response: the systemic effects of a local treatment. Clinics (São Paulo, Brazil) 73(suppl 1): e557s.

- Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack D, Vucic D, French D, et al. (2004) Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature 430 (6996): 213-218.

- Broz Petr, Dixit Vishva M (2016) Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nature Reviews Immunology 16 (7): 407-420.

- Dar TB, Henson RM, Shiao SL (2019) Targeting Innate immunity to enhance the efficacy of radiation therapy. Frontiers in Immunology 9: 3077.

- McKelvey KJ, Hudson AL, Back M, Eade T, Diakos CI (2018) Radiation, inflammation and the immune response in cancer. Mammalian genome. Official Journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society 29(11-12): 843-865.

- Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT (2009) Pyroptosis: Host cell death and inflammation. Nature Reviews (Microbiology) 7(2): 99-109.

- Campbell AM, Decker RH (2018) Harnessing the immunomodulatory effects of radiation therapy. Oncology (Williston Park) 32(7): 370-374.

- Chen PA, Shrivastava G, Balcom EF, McKenzie BA, Fernandes J, et al. (2019) Absent in melanoma 2 regulates tumor cell proliferation in glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol 144(2): 265-273.

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES (2009) AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature 458 (7237): 509-513.

- Karan D (2018) Inflammasomes: Emerging central players in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology 9: 3028.

- Tsuchiya K, Nakajima S, Hosojima S, et al. (2091) Caspase-1 initiates apoptosis in the absence of gasdermin D. Nat Commun 10: 2091.

- Ye Z, Lich JD, Moore CB, Duncan JA, Williams KL, et al. (2008) ATP binding by monarch-1/NLRP12 is critical for its inhibitory function. Mol Cell Biol 28(5): 1841-1850.

- Crowley SM, Knodler LA, Vallance BA (2016) Salmonella and the Inflammasome: Battle for intracellular dominance. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 397: 43-67.

- Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J (2006) Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440(7081): 237-241.

- Hu ZI, McArthur HL, Ho AY (2017) The abscopal effect of radiation therapy: What is it and how can we use it in breast cancer? Current Breast Cancer Reports 9(1): 45-51.

- Marín A, Martín M, Liñán O, Alvarenga F, López M, et al. (2014) Bystander effects and radiotherapy. Reports of Practical Oncology and Radiotherapy 20(1): 12-21.

- Wang R, Zhou T, Liu W, Zuo L (2018) Molecular mechanism of bystander effects and related abscopal/cohort effects in cancer therapy. Oncotarget 9(26): 18637-18647.

- Demaria S, Ng B, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Kawashima N, et al. (2004) Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 58(3): 862-870.

- Ngwa W, Irabor OC, Schoenfeld JD, Hesser J, Demaria S, et al. (2018) Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nature reviews. Cancer 18(5): 313-322.

- Nagasawa H, Little JB (1992) Induction of sister chromatid exchanges by extremely low doses of alpha-particles. Cancer Res 52(22): 6394-6396.

- Shao C, Stewart V, Folkard M, Michael BD, Prise KM (2003) Nitric oxide-mediated signaling in the bystander response of individually targeted glioma cells. Cancer Res 63(23): 8437-8442.

- Burdak-rothkamm S, Short SC, Folkard M, Rothkamm K, Prise KM (2007) ATR-dependent radiation-induced gamma H2AX foci in bystander primary human astrocytes and glioma cells. Oncogene 26(7): 993-1002.

- Golden EB, Chhabra A, Chachoua A, Adams S, Donach M, et al. (2015) Local radiotherapy and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to generate abscopal responses in patients with metastatic solid tumours: A proof-of-principle trial. Lancet Oncol 16(7): 795-803.

- Marconi R, Strolin S, Bossi G, Strigari L (2017) A meta-analysis of the abscopal effect in preclinical models: Is the biologically effective dose a relevant physical trigger? PloS One 12(2): e0171559.

- Vatner RE, Cooper BT, Vanpouille-Box C, Demaria S, Formenti SC (2014) Combinations of immunotherapy and radiation in cancer therapy. Frontiers in Oncology 4: 325.

- Hwang WL, Pike LR, Royce TJ, Mahal BA, Loeffler JS (2018) Safety of combining radiotherapy with immune-checkpoint inhibition. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15(8): 477-494.

- Lamichhane P, Amin NP, Agarwal M, Lamichhane N (2018) Checkpoint inhibition: will combination with radiotherapy and nanoparticle-mediated delivery improve efficacy? Medicines (Basel, Switzerland) 5(4): 114.

- Buchwald ZS, Wynne J, Nasti TH, Zhu S, Mourad WF, et al. (2018) Radiation, immune checkpoint blockade and the abscopal effect: A critical review on timing, dose and fractionation. Frontiers in Oncology 8: 612.

- Beatty GL, Li Y, Long KB (2017) Cancer immunotherapy: activating innate and adaptive immunity through CD40 agonists. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 17(2): 175-186.

- Ishihara J, Ishihara A, Potin L, Hosseinchi P, Fukunaga K, et al. (2018) Improving efficacy and safety of agonistic anti-CD40 antibody through extracellular matrix affinity. Mol Cancer Ther 17(11): 2399-2411.

- Roach MC, Bradley JD, Robinson CG (2018) Optimizing radiation dose and fractionation for the definitive treatment of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Disease 10(Suppl 21): S2465-S2473.

- Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, Khoo V, Birtle A, et al. (2016) Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. The Lancet (Oncology) 17(8):1047-1060.

- Durante M, Bräuer-Krisch E, Hill M (2018) Faster and safer? FLASH ultra-high dose rate in radiotherapy. The British Journal of Radiology 91(1082): 20170628.

- Sologuren I, Rodríguez-Gallego C, Lara P (2014) Immune effects of high dose radiation treatment: Implications of ionizing radiation on the development of bystander and abscopal effects. Translational Cancer Research 3(1): 18-31.

- Montay-gruel P, Petersson K, Jaccard M, et al. (2017) Irradiation in a flash: Unique sparing of memory in mice after whole brain irradiation with dose rates above 100Gy/s. Radiother Oncol 124(3): 365-369.

- Carlson DJ, Stewart RD, Li XA, Jennings K, Wang JZ, et al. (2004) Comparison of in vitro and in vivo alpha/beta ratios for prostate cancer. Phys Med Biol 49(19): 4477-4491.

- Miralbell R, Roberts SA, Zubizarreta E, Hendry JH (2012) Dose-fractionation sensitivity of prostate cancer deduced from radiotherapy outcomes of 5,969 patients in seven international institutional datasets: α/β = 1.4 (0.9-2.2) Gy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82(1): e17-24.

© 2020. Yi Lu. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)