- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Approaches in Cancer Study

HCC: Achieving Complete Response in a Patient After Liver Transplantation, Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Sorafenib Treatment and Radiotherapy Continued with Follow-up

Krzysztof Woźniak1, Malgorzata Osmola1*, Piyush Vyas1, Anna Waszczuk Gajda1, Marta Hałaburda Rola2 and Leszek Kraj1

1Department of Hematology, Oncology and Internal Medicine, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

2Department of Radiology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

*Corresponding author: Malgorzata Osmola, Department of Hematology, Oncology and Internal Medicine, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

Submission: December 03, 2019Published: December 19, 2019

ISSN:2637-773XVolume4 Issue1

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third-leading cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide, accounting for more than 700000 deaths per year [1]. A large proportion of these patients are not candidates for potentially curative therapy, including liver transplantation or local ablation therapy, as they are diagnosed with advanced or metastatic disease. Sorafenib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor used in cases of unresectable, advanced HCC that significantly improves progression-free and overall survival [2]. Achieving complete response with sorafenib is uncommon; however, if complete radiological response is obtained, the issue of the discontinuation of the treatment remains unsolved. There is also no standard of care for patients after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLTx) due to hepatocellular carcinoma and the choice of immunosuppression.

Case

We present a case of a 60-year-old woman with liver cirrhosis due to hepatitis C and B and hemochromatosis complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatitis C genome C type virus diagnosed in 2012 and hepatitis B was eradicated. Patient’s additional comorbidities were well controlled arterial hypertension and nicotinism of 40 pack-years. In March 2013 multiphasic computed tomography (CT) scans demonstrated a 10mm mass with arterial enhancement and early wash-out (HCC-like) in the segment VIII of the liver. There was no evidence of an extra-hepatic spread of the disease. Laboratory tests showed total bilirubin level 2,9mg/dl (normal range, 0.1-1.1mg/dl), albumin 3,3mg/dl (normal range, 4.0-5.5mg/ dl), INR 1,5, serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) 936ng/ml (normal range, 0-7ng/ml). According to liver function classifications, patient was Child-Pugh class B (7 points), and Model for Endstage Liver Disease (MELD) [3] score was 12 points. The cancer was staged as an early stage (A) HCC according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification [4,5].

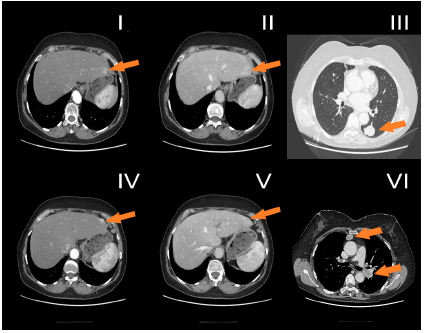

The Patient was qualified for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) procedure, which was performed in June 2014. As a bridging therapy for OLT, trans arterial chemoembolization (TACE) [6,7]- injection of doxorubicin emulsified in lipiodol into the right hepatic artery, was performed twice in August and October 2013. Histopathological examination revealed hepatocellular carcinoma G2, TNM status: pT1Nx, with radical resection. After OLT, the patient received a classical regimen of immunosuppression with steroids and tacrolimus, followed by with tacrolimus in monotherapy (Figure 1). 23-months after OLT, recurrence of HCC was observed, CT scan revealed multiple focal changes in the lungs, up to 30x25mm, mediastinum 30x20mm and liver, in segment II and II/III - 2 focal changes 11mm and 12mm (Figure 2).

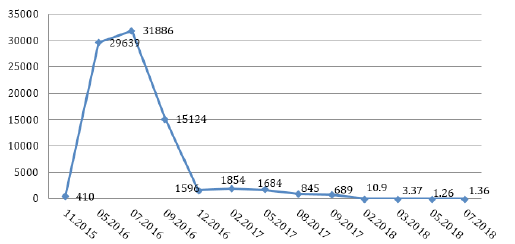

Clinically, the patient’s Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was 0 [8]. Additional laboratory results were as follows: white blood cells 5,3/mm3, haemoglobin level 14.7g/dl, platelet count 117×103/mm3, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 64IU/l (normal range, 0-40IU/l), total bilirubin 0,54mg/dl, albumin 4,2mg/dl, INR 1. The AFP concentration was 29600 ng/ml. The disease was staged as advanced (C) HCC according to BCLC classification, and as stage IV B according to UICC TNM classification. Regarding the patient’s good performance status and preserved liver function, Child-Pugh class A (5 points), the patient was qualified for the first line systemic therapy with sorafenib. Sorafenib at the dose of 800mg/day was started in June 2016. After 3 and 6 months of the therapy, CT scans revealed partial response (PR) according to the mRECIST [9] criteria and the serum AFP level had decreased (Figure 1). During sorafenib treatment, the patient experienced severe toxicities of 2nd and 3rd grade according to CTCAE v. 5.0 criteria: weight loss (sixteen kilograms during 6 months of treatment), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevation, fatigue, diarrhoea. Due to observed toxicities, the sorafenib dose was reduced to 400mg per day.

Figure 1: AFP concentration during sorafenib treatment.

Figure 2: Computed tomography axial planes obtained in arterial phase (I, IV) and portal phase (II, V). Focal lesions located in liver the in seg II (I, II) and II/III (IV, V), enhanced in the arterial phase (I, IV) with typical washout in portal venous phase (II, IV). Metastases in seg. VI of the left lung (III) and to hilar lymph node and mediastinum (VI).

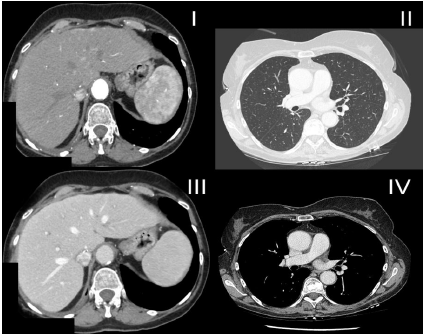

After 20 months of therapy, a PR by CT scan was observed, beside one focal change in the lower lobe of the right lung (20x24mm). To exclude the primary tumour of the lung, due to patient’s history of smoking, a biopsy of the right lung was performed, revealing HCC on histopathological examination. PET-CT scan with FDG was also done and did not revealed any other suspect changes. In January 2018, the patient was qualified for stereotactic radiotherapy of a focal change in the right lung, the Rapid Arc 4D technique, up to a dose of 54Gy (3x 18Gy) was performed. Stereotactic radiotherapy was well tolerated. On a control CT scan there was one residual change (13x11mm), and AFP had decreased to normal values. Due to severe toxicities of the systemic therapy and upon achieving a complete response (CR), sorafenib treatment was discontinued. All toxicities caused by sorafenib were reversible. Since March 2018, the patient is under oncological ambulatory surveillance. After 14 months of follow-up, the patient maintains a complete remission (Figure 3). A Standard immunosuppression protocol with calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus) has been continued. Since April 2019, the patient has been treated with glecaprevir and pibrentasvir for hepatitis C. In July 2019, the patient underwent a control computed tomography, which revealed no signs of recurrence. AFP level has stayed within normal values.

Figure 3: Complete response observed in the liver (I, III), in the lungs (II) and mediastinum (IV).

Discussion

Sorafenib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor used in advanced, unresectable HCC, that significantly improves progression-free and overall survival. The efficacy of sorafenib in advanced HCC was demonstrated in two large phase III clinical trials including the Sorafenib HCC Assessment Randomized Protocol (SHARP) trial and the Asia-Pacific trial [2,10]. In the SHARP trial, only 2% of patients achieved partial response (PR), there was no case of a complete response (CR). CR is uncommon, only few cases were reported worldwide [11-15]; however, if partial or complete radiological response are obtained, the issue to discontinue sorafenib remains unresolved. In our case, the decision on discontinuation was made, due to observed toxicities (grade 3).

There are cases in the literature describing discontinuation of sorafenib after achieving a complete response (CR), when significant toxicities where absent [11]. More data is needed to establish in which group of patients sorafenib can be safely discontinued. There is no standard of treatment of HCC after orthotopic liver transplantation. Our case shows also effectiveness of stereotactic radiotherapy (SBRT), which should be considered in selected patients. Another issue is the choice of an immunosuppression protocol in patients after OLTx due to HCC, during the treatment of recurrence. Our patient was treated according to standard immunosuppression protocol [16] using an inhibitor of calcineurin - tacrolimus and glicocortoicosteroids after liver transplantation followed by tacrolimus in monotherapy. There are data that tacrolimus may promote tumour progression via nonimmune- mediated pathways [17,18]. That is why after OLTx per HCC protocols without calcineurin inhibitors should be considered. The treatment of patients with a recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after liver transplantation is a challenge for a multidisciplinary team that should consists of medical oncologists, hepatic surgeons, transplantologists, infectious disease specialists and radiation oncologists.

References

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65(2): 87-108.

- Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, et al. (2008) Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 359(4): 378-390.

- Kamath PS, Kim WR, Advanced Liver Disease Study Group (2007) The model for end stage liver disease (MELD). Hepatology 45(3): 797-805.

- Llovet J, Brú C, Bruix J (1999) Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: The BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis 19(3): 329-338.

- Kinoshita A, Onoda H, Fushiya N, Koike K, Nishino H, et al. (2015) Staging systems for hepatocellular carcinoma: Current status and future perspectives. World J Hepatol 7(3): 406-424.

- Coletta M, Nicolini D, Benedetti Cacciaguerra A, Mazzocato S, Rossi R, et al. (2017) Bridging patients with hepatocellular cancer waiting for liver transplant: all the patients are the same? Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2:78.

- Decaens T, Roudot Thoraval F, Bresson Hadni S, Meyer C, Gugenheim J, et al. (2005) Impact of pretransplantation transarterial chemoembolization on survival and recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transplant 11(7): 767-775.

- Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, et al. (1982) Toxicity and response criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin Oncol 5(6): 649-655.

- Lencioni R, Llovet J (2010) Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 30(1): 52-60.

- Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, et al. (2009) Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 10(1): 25-34.

- Takeda Y, Ohmura Y, Katsura Y, Sakamoto T, Nose Y, et al. (2019) Sustained complete response of hepatocellular carcinoma with multiple intrahepatic metastases following the discontinuation of sorafenib. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 46(3): 532-536.

- Park JG, Tak WY, Park SY, Kweon YO, Jang SY, et al. (2017) Long-term follow-up of complete remission of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following sorafenib therapy: A case report. Oncol Lett 14(4): 4853-4856.

- Park JG (2015) Long-term outcomes of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who achieved complete remission after sorafenib therapy. Clin Mol Hepatol 21(3) :287-294.

- Kim MS, Jin YJ, Lee JW, Lee JI, Kim YS, et al. (2013) Complete remission of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma by sorafenib: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 5(2): 38-42.

- Liu D, Liu A, Peng J, Hu Y, Feng X (2015) Case analysis of complete remission of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma achieved with sorafenib. Eur J Med Res 20(1): 12.

- Durlik M, Zieniewicz K (2016) Zalecenia dotyczące leczenia immunosupresyjnego po przeszczepieniu narządów unaczynionych. Opracowaneprzez Polskie Towarzystwo Transplantacyjne Zalecenia_Immunopresyjne 13: 35:43

- Hojo M, Morimoto T, Maluccio M, Asano T, Morimoto K, et al. (1999) Cyclosporine induces cancer progression by a cell-autonomous mechanism. Nature 397(6719): 530-534.

- Maluccio M, Sharma V, Lagman M, Vyas S, Yang H, et al. (2003) Tacrolimus enhances transforming growth factor-beta1 expression and promotes tumor progression. Transplantation 76(3): 597-602.

© 2019 Malgorzata Osmola. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)