- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Approaches in Cancer Study

Research Proposal Self-Management and Commitment for Cancer Patients

Sitvast J*

Department of Applied Sciences, Netherlands

*Corresponding author:Sitvast J, Department of Applied Sciences, Utrecht, Netherlands

Submission: April 04, 2019;Published: April 18, 2019

ISSN:2637-773XVolume2 Issue4

Introduction

In the Netherlands a new concept of health has been introduced by Huber et al. [1]. “Health is the capacity of people to adapt and direct their coping with adversities of life against the background of physical, emotional and social challenges. Being healthy means to be able to adapt to disruptions, show resilience and maintain a balance of refined this balance physically, mentally and socially.” This definition of health has increasingly been adopted in health care and has also entered the Dutch professional profile for nurses [2]. No longer (the concept of) health is looked upon as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being as it used to be formulated by the WHO in the nineties, implicating then that many people must be classified as ill even where they coped with their disease very well and they themselves would not describe themselves as ill. The new concept of health considers health a positive asset and is therefore sometimes labeled as ‘positive health’.

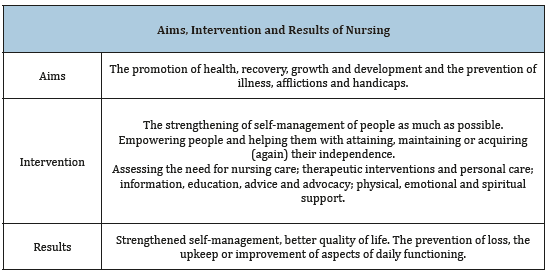

In the professional profile the promotion of health is seen as the core of nursing [2]. Seen in the light of the new definition of health this means: Maintaining or acquiring (again) independence in health issues and daily functioning are the most important aspects of selfmanagement [3]. A crucial element in self-management is the process of meaning giving. Let us see how this has been embedded in domains of health. Huber et al distinguishes 6 domains of health, namely: the physical, the mental, the spiritual/existential and the social dimension, quality of life and general daily skills. As patients responded: ‘Positive health concerns life in all its aspects.’ ‘Positive health’ can be characterized by diffuse demarcation lines between care and the social domain. It can be postulated that how a person and his social environment looks upon health from the perspectives and also how it affects daily life and social interaction determines the actions this person will take for self-management. For instance, a seventyyear old patient with bladder cancer will invest more willingly in learning how to handle his stoma and follow life style advice when he knows that it enables him to go for a walk in the park with his grandchildren, as this contributes enormously to his quality of life (Table 1). We expect that by supporting people in all aspects of positive health their resilience and capacity for self-management will be strengthened and that quality of life will improve [4]. In order to achieve these results, the following issues are important:

Table 1:Aims, intervention and results of actions by nurses [2].

A. Awareness and education;

B. Establishing what we really think is of value to us;

C. Self-management: an attitude that matches our conduct to the values we strife after.

In this way things of value will be protected [4]. This ties in with another new development: we move into an era of personalized health care with treatment ‘tailored’ to the specific individual needs of the patient. For mental health care the Dutch government made these one of the two research themes for which money will be granted. But also, in general health care this will be the norm more and more [5].

On a conference on disease management in the Netherlands in 2014, researchers brought forward that the perspective of the professional dominates; there is (still) relatively little attention for the perspective of the patient. How can caregivers help patients reflect on their life with a chronic illness and give meaning to it? This kind of reflection may be part of the motivational counseling that precedes participation in self-management programs or runs parallel with it. However, where these reflections remain private thoughts shared only with a caregiver and do not make an integral part of a storying process stretched out over a longer period, then its relevance and importance will be fragmentary. How to facilitate reflections on how to live a valued life with a chronic illness is a topic that has not yet met much attention in literature. The facilitation of these reflections will be the topic of our research [6]. We propose to support the reflections with the use of the so-called values compass that has been developed in the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in mental health care [7].

The requirements of self-motivation in self-management in this respect may be summarized as follows: there must be a focus on reflection by patients on the lived experiences of illness and, as we postulate, also on how these relate to a so called “valued life”: a life that is seen as meaningful by patients. The articulation of this perspective must not be interfered too much by the professional’s interest in fitting the patient in the existing self-management programs. There must be room and ample time for dialogue and sharing with professionals and other patients. Only then can a collaborative problem-solving and goal setting be built (Shared Decision Making). This is our evaluation framework with which we pose the following question: How can the articulation of the patient perspective (values) facilitated by the care professional using a therapeutic intervention and how can this be used to promote motivation for self-management [6].

The Intervention

Photography as a therapeutic medium will be used as instrument. Patients will make photographs supported by assignments. Patients will then be invited to reflect on these photographs and make them part of a visual narrative. The focus will be on how to live a valued life with cancer and what this means for illness management, lifestyle decisions, spirituality, etc. A first pilot was done in 2016 [8]. The photo-instrument, developed by the author Sitvast et al. [6,9] will be the intervention that will be researched for its effectiveness to inspire patients to goal setting in the context of self-management and shared decision making. To that aim the intervention as has been developed by Sitvast et al. [6,8,10] and tested in the Netherlands will be adapted to the focus of the ‘values compass’ [11] and then implemented and pilot tested again to fit local context and specific target population. The aim of the intervention will be to generate an inventory of values (the so called “values compass’’) –made visible in photographs and storied in narrative-that serves the patient to make better choices for his individual self-management or recovery trajectory.

The Research Designs

The target population will be patients who live with cancer or have recovered from cancer and who must refine a balance in life: physically, mentally and socially. The first part of the research will focus on how the articulation of the patient perspective (values compass) is facilitated by nurses using the photo-instrument [6]. The design will be qualitative, ethnographic and hermeneutic. The second part will be a research into the utility of the values compass to be a starting point for motivating patients for self-management or recovery [12]. The linkage between the exploration of values in a values compass and how this compass can be used in a dialogue between care professionals and the patient will be explored with mixed methods which still must be defined.

Result

A multi-case study in which nursing students assemble data and have a role in implementing the intervention. Their role (whether it will be more executive or more research-oriented) depends on the level of training: bachelor or master.

References

- Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, Horst HV, Jadad AR, et al. (2011) How should we define health? BMJ 343: d4163.

- Schuurmans M (2012) Policy report. In: Verpleegkundigen and Verzorgenden (Eds), VenVN, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- Sassen B (2018) Nursing: Health education and improving patient selfmanagement. Springer.

- Huber M, Staps S (2016) Self-management for health and environment: Time for a new approach-position paper. Louis Bolk Instituut en Institute for Positive Health White Paper.

- Vlek H, Driessen S, Hassink L (2014) Persoonsgerichte zorg (Translation: Personcentred Care). White paper, Vilans knowledge center, Utrecht, Netherlands.

- Sitvast J (2013) Self-management and representation of reality in photostories. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 36(4): 336-350.

- https://thehappinesstrap.com/upimages/Complete_Worksheets_2014

- Sitvast J (2016) A case study “A life with and beyond Cancer”. Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine 6(3): 266.

- Sitvast J, Abma TA, Lendemeijer HHGM, Widdershoven GAM (2008) Photo stories, ricoeur, and experiences from practice: A Hermeneutic Dialogue. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 31(3): 268-279.

- Sitvast J (2017a) Commentary on a case study “A life with and beyond cancer”. J of Mol Oncol Res 1(1): 4.

- Sitvast J (2017) Photography as a means to overcome health anxiety and increase vitality, a local group intervention in an ailing city district. SF Nurs Heal J 1:1.

- Huber M, Vliet MV, Giezenberg M, Winkens B, Dagnelie PC, et al. (2016) Towards a ‘patient-centred’ operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 6(1): 1-11.

© 2019 Sitvast J. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)