- Submissions

Full Text

Medical & Surgical Ophthalmology Research

The Value of Using a Virtual Clinic in the Optimal Management of Glaucoma Patients in an Island Population in the UK

Elewys Hearne1 and Sue Lightman2*

1Department of Ophthalmology, Royal United Hospital, UK

2Department of Clinical Ophthalmology UCL/IOO, University of the Highlands and Islands, UK

*Corresponding author: Sue Lightman, Department of Clinical Ophthalmology UCL/IOO, University of the Highlands and Islands, UK

Submission: June 22, 2021;Published: July 14, 2021

ISSN 2578-0360 Volume3 Issue2

Abstract

Purpose: To identify the value of asynchronous virtual glaucoma clinics in the detection of ocular

morbidity from glaucoma in a remote and rural population in the UK.

Methods: On Orkney clinics were set up using the Royal College of Ophthalmologists guidelines for

virtual glaucoma clinics. Patients taken consecutively from the waiting lists for clinic appointments, were

sent a letter explaining the asynchronous virtual clinic process and given a date and time to come for

measurement of visual acuity, intraocular pressure as well as Humphrey visual field testing and OCT of

the optic disc. Medication was recorded. Nurses and health care workers were trained to undertake all

these tests. All the patients’ results were put onto a specifically designed proforma, visual fields printed

and collected, OCTs were digitally stored, and all reviewed by the Ophthalmologist. The Ophthalmologist

went through the virtual clinical data comparing where possible with previous data and decided on

management options 1) patient stable - see 1 year, 2) some changes but eye pressure stable or no previous

data found for example unsure of age of visual field defect, see in 6 months, 3) Patients with high IOPs are

booked into the next available clinic for urgent management. Patients are written to with the outcome of

their clinic and a copy sent to their GP and optometrist.

Results: Over 1 year 112 patients were seen in the asynchronous virtual clinics. 109 of the patients

seen had glaucoma, 3 had uveitis and were not included in the data analysis. Of the 109 patients the vast

majority had chronic open angle glaucoma, with 10 narrow angle/closed angle, 8 ocular hypertensives

and 2 uveitic glaucoma. Of these patients 35 were stable and given an appointment to be reviewed in a

year. 35 patients were to be seen again in 6 months rather than 1 year due to problems with assessment,

such as no previous visual field for comparison, but eye pressures were controlled. 39 patients were asked

to come into the next clinic to be seen by the Ophthalmologist as their IOP was too high or there were

concerns about increasing visual field loss. When the management was changed the patient was booked

into the eye clinic in approximately 2 months for an IOP check.

Conclusion: The asynchronous virtual clinic is a way of maintaining regular review for significant

numbers of patients that can be seen and managed and has the safety net that patients can be reviewed

urgently if necessary

Keywords:Asynchronous; Virtual clinic; Glaucoma; Ocular morbidity; Health; Humphrey visual; Optometrist; Chronic

Abbreviations:SARS-CoV-2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2; IOP: Intra Ocular Pressure; VF: Visual Field

Introduction

Glaucoma is the most common cause of irreversible sight loss worldwide [1] and the prevalence is predicted to increase by almost 50% in the UK over the next 20 years [2]. This rapidly rising prevalence in the UK is due to the aging population [3], and advances/ availability in diagnostic technology such as visual field and OCT machines in primary care which have resulted in more referrals to glaucoma clinics than ever before [4]. As glaucoma is a chronic condition, patients once diagnosed require lifelong follow up and along with the fact that the UK has the one of the lowest number of ophthalmologists per capita within the developed world [5] has given rise to the glaucoma service demand outstripping its supply, long before this current pandemic presented additional logistical problems. This has stemmed a huge need to redesign glaucoma patient pathways to improve capacity [3] as previous attempts including recruiting more clinicians, putting on weekend clinics and electronic appointment tracker systems have still not managed to provide capacity to allow patients to be seen and followed up by the glaucoma service in line with NICE guidelines released in 2017 [6,7]. The current pandemic presents an opportunity to utilise digital transformation to address the glaucoma patient pathway capacity issues. SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2) infection was pronounced a global pandemic in March 2020 [8]. This extraordinary and unique situation created a rare opportunity to drive change using technology to reduce person to person contact when delivering eye healthcare [9].

The Kings Fund [10] described the incredible speed of leadership decision-making and examples of collaboration embraced with minimal resistance [10]. The 2020/21 People Plan highlights that the pandemic has created a huge catalyst to implement change and a setting whereby governance has been simplified [11]. The swift and colossal digital transformation includes commonplace video consultations which were previously rare in primary and secondary care as well as virtual multidisciplinary team meetings, handovers, and teaching sessions across primary and secondary care [11,12]. The minimal resistance to change has also been put down to National Health Service (NHS) staff experiencing shared purpose, which is the core component on the NHS leadership model [13].

A virtual clinic is described as there being no face to face

interaction between the doctor and the patient. The clinic has two

different components:

i. Data collection: A technician/non-specialist nurses

orthoptist or optometrist collects the clinical measurements in

a hospital outpatient clinic, a community clinic or mobile unit

and the patient then goes home

ii. An appropriately trained healthcare professional reviews

the patient data and outcomes are written in a letter to the

patient [14].

This structure allows the healthcare professional to review many more patients’ data than the traditional clinic set up. Virtual glaucoma clinics can be used in both glaucoma detection and referral as well as diagnosis and management of glaucoma. The virtual clinic model has been shown to be very effective in reducing the large burden of community referrals. In Portsmouth whereby virtual clinics were used to triage [15] and refine [16] community referrals revealed only 11% of the referrals required the hospital eye service, which released 1400 clinic slots per year to the NHS trust [17]. Virtual clinics have even been found to detect more cases of glaucoma than in-person examination [18]. In addition, patient education has not been found to suffer in virtual clinics, as patients in one study demonstrated an equivalent level of knowledge of glaucoma in face-to-face clinics when compared to virtual clinics [19]. Clearly in remote and underserviced communities with no resident ophthalmologists, virtual glaucoma clinics present the advantage of earlier detection and reduced travel for the patients/ staff. For the hospital eye units there are reduced waiting lists and cost savings.

Methods

The aim of this study was to identify the value of asynchronous

virtual glaucoma clinics in the detection of ocular morbidity

from glaucoma in Orkney, a remote and rural population in the

UK. The delivery of ophthalmic care in Orkney is by the resident

optometrists and visiting consultant ophthalmologists to the

Balfour Hospital assisted by a visiting optometrist and orthoptist.

Glaucoma patients were previously seen in the general eye clinics

but the space in these clinics was very limited as glaucoma patients

were usually not considered high priority for the limited number of

appointments available as they have chronic rather acute disease.

On Orkney in 2019 virtual glaucoma clinics were set up using the

Royal College of Ophthalmologists guidelines for virtual glaucoma

clinics. Patients taken consecutively from the waiting lists for clinic

appointments, were sent a letter explaining the asynchronous

virtual clinic process and given a date and time to come for

measurement of visual acuity, Reinhardt intraocular pressure (IOP)

as well as Humphrey Visual Field testing (VF) and OCT (Topcon)

of the optic disc. Medication was recorded. Nurses and health care

workers were trained to undertake all these tests. These virtual

clinics were run 1-4 weeks before the Ophthalmologist was due to

visit the island. All the patients’ results were put onto a specifically

designed proforma, VF printed and collected, OCTs were digitally

stored, and all reviewed by the Ophthalmologist when next on the

island. The Ophthalmologist went through the collected clinical

data comparing where possible with previously recorded patient

data were available and decided on management options

a. Group 1=Patient stable-see in 1 year.

b. Group 2=Some visual field or OCT changes or no previous

data found for example unsure of age of visual field defect but

eye pressure well controlled, see in 6 months.

c. Group 3=Patients with high IOPs were booked into the

next available clinic for urgent management.

Patients were written to with the outcome of their clinic visit by the Ophthalmologist and a copy sent to their GP and optometrist. The GP was asked to prescribe the medication and the patients would see their GP if they experienced any side effects. The ophthalmology consultant was contacted by email for a decision on action regarding side effects. All patients in whom medication was changed were seen at 3 months in the Consultant clinic.

Result

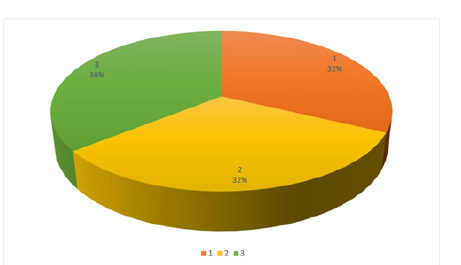

Over 1 year (2019-2020) 112 patients were seen in the asynchronous virtual clinics many of whom had not been seen for at least 2 years, and many longer than that. 109 of the patients seen had glaucoma, whilst 3 had uveitis and no glaucoma, and therefore were not included in the data analysis. Of the 109 patients the vast majority had chronic open angle glaucoma, with 10 narrow angle/ closed angle, 8 ocular hypertensives and 2 with uveitic glaucoma. The patients were spread fairly equally across the three groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pie chart illustrating the groups allocated to the glaucoma virtual clinic patients.

i. In Group 1 the patient was stable: 35 patients (32%) were

in this group, stable and given an appointment to be reviewed

in a year.

ii. In Group 2 some visual field or OCT changes or no

previous data found for example unsure of age of visual field

defect but eye pressure well controlled. 35 patients (32%) were

in this group and were to be seen again in 6 months rather than

1 year due to problems with assessment, such as no previous

VF for comparison, but eye pressures were well controlled.

iii. In Group 3 patients had high IOPs. There were 39 patients

(36%) in this group, and they were asked to come into the

next clinic to be seen by the Ophthalmologist as their IOP was

too high or there were concerns about increasing visual field

loss or OCT nerve fibre layer thinning. When the management

was then changed the patient was booked into the eye clinic in

approximately 2 months for a further IOP check.

The hospital administration understood the need for this clinic set up and provided financial and logistical support for purchase of equipment, trading of staff and clinic space. Patients were very compliant, and attendance was excellent. The few patients that did attend not were invited to the next clinic. Staff were keen to be involved and get trained. The IOP in the patients seen in both the virtual clinic and in the consultants, clinic was very similar, showing validity in IOP measurements in both clinics.

Discussion

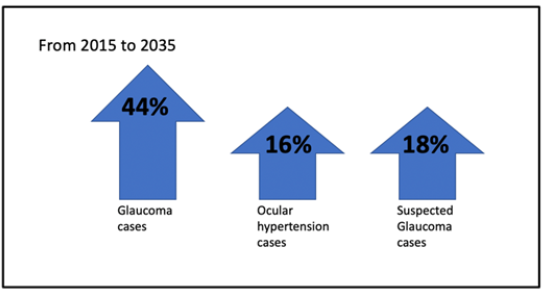

Figure 2: From 2015 to 2035 glaucoma cases are predicted to rise by 44%, ocular hypertension cases are predicted to rise by 16% and suspected glaucoma cases are predicted to rise by 18% in the UK. These conditions are currently all managed by the glaucoma service. Most glaucoma services are already experiencing patient numbers beyond their capacity. Figure altered from [20].

This study confirms the values of establishing virtual clinics to safely deal with the increased glaucoma patient demand. The detection and monitoring of glaucoma is a huge challenge, especially with the prevalence of glaucoma predicted to increase by almost 50% in the UK over the next 20 years [2] (Figure 2) due to the rising elderly population. The challenge is even greater in rural and remote areas, and these virtual clinics allow more patients to be reviewed by the ophthalmologist than in conventional clinics. Virtual glaucoma clinics offer a route to improve the efficiency of detection, increase capacity for review appointments and standardise of the quality of care given in monitoring as shown in our study. Further developments will include digitising all the collected data so that they can be reviewed remotely, and this will further increase the efficiency of the service [20].

Half of hospital eye service units in the United Kingdom have begun using virtual glaucoma clinics for surveillance of their glaucoma patients, and many others are seeking to develop them [21]. The current pandemic presented a great opportunity to construct these services across the United Kingdom. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists has constructed Standards for Virtual Clinics in Glaucoma Care [3], which also describes suitable patients, investigations, staffing, data collection and governance. Virtual glaucoma clinics have been reported as safe, with misclassification occurring at 1.9% [22]. They are also well accepted by the patients [23-25]. Clinicians have described barriers such as taking away the face-to-face element of decision-making [20], lacking the required staffing, time, funding and space to perform virtual clinics, although those in acute trusts or major teaching hospitals were found to be more likely to conquer these barriers [21]. In the future, it may well be that glaucoma referrals and surveillance become very similar to the extremely successful Diabetic Retinopathy Screening programme. Artificial Intelligence algorithms have also been shown to have promising accuracy in glaucoma detection [26].

Conclusion

The set up and running of the asynchronous virtual clinic in Orkney has shown the way for maintaining regular review for significant numbers of patients that can be seen and managed and has the safety net that patients can be reviewed urgently if necessary. This model is sustainable and can be repeated in other settings so that the visual morbidity from glaucoma is significantly reduced as patients are regularly monitored and are looked after by experienced ophthalmologists to ensure optimal care. In the future the Orkney glaucoma service may include a virtual clinic for glaucoma referrals also which has proven to be very successful in other settings.

References

- Li T, Lindsley K, Rouse B, Hong H, Shi Q, et al. (2016) Comparative effectiveness of first-line medications for primary open-angle glaucoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 123(1): 129-140.

- Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, et al. (2014) Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 121(11): 2081-2090.

- (2016) Ophthalmic Services Guidance: Standards for virtual clinics in glaucoma care in the NHS Hospital Eye Service. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, pp. 1-9.

- Ratnarajan G, Newsom W, French K, Kean J, Chang L, et al. (2013) The impact of glaucoma referral refinement criteria on referral to, and first-visit discharge rates from, the hospital eye service: The Health Innovation & Education Cluster (HIEC) Glaucoma Pathways project. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 33(2): 183-189.

- Resnikoff SFW, Gauthier TM, Spivey B (2012) The number of ophthalmologists in practice and training worldwide: A growing gap despite more than 200,000 practitioners. Br J Ophthalmol 96(6): 783-787.

- Batra R, Sharma HE, Elaraoud I, Mohamed S (2018) Resource planning in glaucoma: A tool to evaluate glaucoma service capacity. Semin Ophthalmol 33(6): 733-738.

- (2017) NICE Guidelines on Glaucoma: Diagnosis and Management.

- (2020) World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

- Heimann H, Broadbent D, Cheeseman R (2020) Digital ophthalmology in the UK-Diabetic retinopathy screening and virtual glaucoma clinics in the National Health Service. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 237(12): 1400-1408.

- (2020) The Kings Fund. Covid-19: Why compassionate leadership matters in a crisis. UK.

- (2020) NHS England. WE are the NHS: People Plan 2020/21-action for us all. UK.

- Inkster B, Brien OR, Selby E, Joshi S, Subramanian V, et al. (2020) Digital health management during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic: Opportunities, barriers, and recommendations. JMIR Ment Health 7(7):

- (2020) Leadership Academy. NHS Leadership Model. pp. 1-16.

- Wright HR, Diamond JP (2015) Service innovation in glaucoma management: Using a Web-based electronic patient record to facilitate virtual specialist supervision of a shared care glaucoma programme. Br J Ophthalmol 99(3): 313-317.

- Rathod D, Win T, Pickering S, Austin M (2008) Incorporation of a virtual assessment into a care pathway for initial glaucoma management: Feasibility study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 36(6): 543-546.

- Trikha S, Macgregor C, Jeffery M, Kirwan J (2012) The Portsmouth-based glaucoma refinement scheme: A role for virtual clinics in the future? Eye (Lond) 26(10): 1288-1294.

- Harper RA, Gunn PJG, Spry PGD, Fenerty CH, Lawrenson JG (2020) Care pathways for glaucoma detection and monitoring in the UK. Eye (Lond) 34(1): 89-102.

- Thomas SM, Jeyaraman MM, Hodge WG, Hutnik C, Costella J, et al. (2014) The effectiveness of teleglaucoma versus in-patient examination for glaucoma screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 9(12):

- Tatham AJ, Ali AM, Hillier N (2021) Knowledge of glaucoma among patients attending virtual and face-to-face glaucoma clinics. J Glaucoma 30(4): 325-331.

- Gunn PJG, Marks JR, Au L, Waterman H, Spry PGD, et al. (2018) Acceptability and use of glaucoma virtual clinics in the UK: A national survey of clinical leads. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 3(1): 1-7.

- (2016) The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. The Way Forward. UK, pp. 1-44.

- Clarke J, Puertas R, Kotecha A, Foster PJ, Barton K (2017) Virtual clinics in glaucoma care: Face-to-face versus remote decision-making. Br J Ophthalmol 101(7): 892-895.

- Kotecha A, Bonstein K, Cable R, Cammack J, Clipston J, et al. (2015) Qualitative investigation of patients' experience of a glaucoma virtual clinic in a specialist ophthalmic hospital in London, UK. BMJ Open 5(12): 1-9.

- Court JH, Austin MW (2015) Virtual glaucoma clinics: Patient acceptance and quality of patient education compared to standard clinics. Clin Ophthalmol 9: 745-749.

- Spackman W, Waqar S, Booth A (2021) Patient satisfaction with the virtual glaucoma clinic. Eye (Lond) 35(3): 1017-1018.

- Mursch-Edlmayr AS, Siene NW, Diniz Filho A, Sousa DC, Arnold L, et al. (2020) Artificial Intelligence algorithms to diagnose glaucoma and detect glaucoma progression: Translation to clinical practice. Transl Vis Sci Technol 9(2): 55.

© 2021 Sue Lightman. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)