- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Research in Dentistry

A Study of the Incidence and Distribution of Sinus Tract in Patients Referred for Endodontic Therapy in a Population in Argentina

Pablo Ensinas1*, Andres Pantanali2 and Ramiro Caba Cabrera2

1 Director of the Specialty Course in Endodontics, Argentina

2 Teacher in the Post-Graduate Course in Endodontics, Argentina

*Corresponding author: Dr. Pablo Ensinas, Director of the Specialty Course in Endodontics, Mar Antártico 1125, Bº San Remo, Salta, Argentine Republic, Postal Code: 4400, Argentina

Submission: March 29, 2018;Published: April 25, 2018

ISSN:2637-7764Volume2 Issue3

Abstract

Introduction: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the incidence and distribution of sinus tract in a population in the North West of Argentina.

Methods: The study evaluated 524 patients in need of endodontic therapy over a period of 16 months, in a post-graduate course on endodontics in the Province of Jujuy, Argentine Republic. The incidence of sinus tract together with their distribution by tooth, endodontic disease, gender and age were evaluated using a logistic regression test and Fisher’s exact test.

Results: The incidence of sinus tract was 15.3% (n=80). There were no significant differences in age and gender (P<0.05). The tooth with the highest tendency to sinus tract is the lower first molar (26.3%) followed by the upper incisors (20%) and the most frequent disease was necrosis with radiolucent lesion (58.25%). Results show that only disease had a significant effect on the dependent variable (P<0.05).

Conclusion: Knowledge of the incidence and distribution of sinus tract is essential for locating infectious foci and diagnosing involved teeth.

Keywords: Endodontics; Sinus tract; Epidemiology; Incidence; Chronic infection

Introduction

Dental sinus tract is one of the manifestations of chronic pulp infections. It is caused by pus in search of a drainage route following the path of least resistance through bone, periosteum and mucosa [1]. The American Association of Endodontists defines it as a passage of pus from a closed infection area to an epithelial surface [2].

The sinus tract may open intraorally or extraorally, depending on the resistance of the bone to the outflow of exudate, the distance from the root apex to the buccal cortical bone, bone morphology and face muscle attachments [3-5].

An intraoral outflow normally indicates the presence of necrotic pulp or a chronic apical abscess and sometimes of a periodontal abscess. Placing a gutta-percha point in the sinus tract helps to locate the source of these lesions radiographically.

An extraoral opening or a skin sinus tract may be confused with a wide variety of conditions including local skin infection, inward hair growth or blocked sweat-gland duct, osteomyelitis, neoplasms, tuberculosis, actinomycosis and congenital upper lip sinus tract [3,6-11].

Various authors have reported the presence of sinus tract. However, few have evaluated their prevalence in a specific population from the epidemiological point of view [5,10]. The purpose of this study was to determine the incidence of dental sinus tract in patients referred for endodontic therapy in a postgraduate course on endodontics held at the Círculo Odontológico de Jujuy and their distribution by tooth, pulp disease, gender and age group.

Materials and Methods

This study covers 524 patients who presented for endodontic therapy to the post-graduate endodontics clinic of the Círculo Odontológico of the Province of Jujuy, Argentina, during the 16-month period between February 2016 and May 2017.

The inclusion criteria encompassed any patients who in their clinical record had no history of pre-existing chronic conditions and who were not under antibiotic treatment prior to the endodontic visit. Any sinus tract on teeth scheduled for extraction due to root fissure or fracture were excluded as well as any sinus tract related to deciduous dentition diseases.

Patients were questioned about their general health and main complaint and signed an informed consent form in which they voluntarily accepted to participate in this study. In the case of minors, the informed consent form was signed by a parent or legal guardian.

All the fistulous teeth were clinically evaluated to identify pulp disease using a thermal test with Endo-Frost spray (Roeko Coltene/ Whaledent-Langenau, Germany) and periapical X-rays. A guttapercha point was placed through the sinus tract for the periapical X-rays to determine its relationship with the tooth of origin.

The diseases evaluated were classified as follows:

a) Pulpitis

b) Necrosis without visible X-ray lesion

c) Necrosis with visible radiolucent lesion

d) Retreatment without visible radiolucent lesion

e) Retreatment with visible radiolucent lesion

The patients, whose ages ranged from 10 to 70 years, were divided into two groups; patients older than 30 years of age and patients under 30 years old. Patients were divided into male and female for the gender variable. The data were loaded on a specially designed Excel sheet and evaluated using a logistic regression test and Fisher’s exact test.

Results

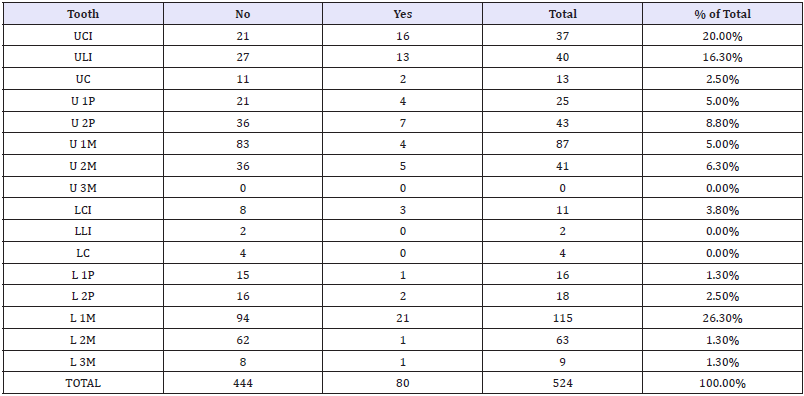

The incidence of sinus tract in the study population was 15.3% (n=80). Of the total number of sinus tract (15.3%) the highest proportion 26.3% (n=21) corresponded to the lower first molar followed by the upper central incisors 20% (n=16) whilst the lower lateral incisors and canines together with the upper third molars did not present any sinus tract (Table 1).

Table 1: Sinus tract distribution by tooth.

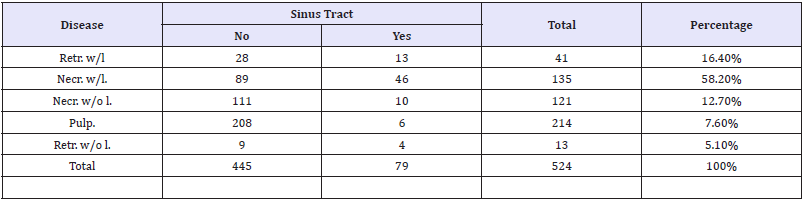

The disease with the highest tendency to fistulization was necrosis with radiolucent lesion 58.25% (n=46) followed, with a lower percentage, by endodontic retreatment with radiolucent lesion 16.4% (n=13) (Table 2).

Table 2: Sinus tract distribution by tooth.

A total of 286 females and 238 males were seen. Of the total number of women, 14.7% (n=42) had sinus tract. The percentage was 15.5% (n=37) for males. Gender difference was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test and was not significant (P=0.81).

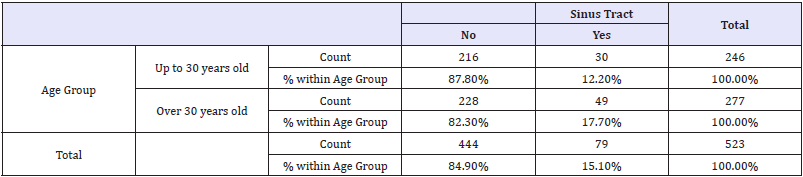

There was no significant difference between age groups (Fisher’s exact test, P=0.08). There was a slight tendency to a higher frequency of sinus tract at an older age but this did not reach statistical significance (Table 3).

Table 3: Sinus tract-age group contingency table.

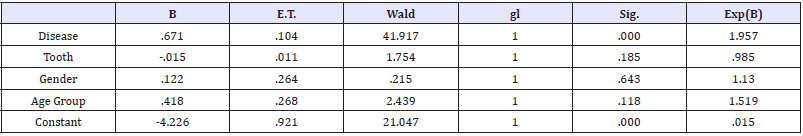

The influence of the four factors (disease, tooth, gender and age group) on the presence or not of a sinus tract was evaluated by logistic regression analysis. The results show that only disease has a significant effect on the dependent variable (P<0.05). A factor interaction analysis shows a significant effect between tooth and disease (Table 4).

Table 4: Sinus tract distribution by tooth.

Discussion

Colonization of root canals by different organisms causes a chronic inflammatory reaction in periapical tissues which can be exteriorized through a sinus tract [12,13]. It is important for the clinician to take into account that the location of the sinus tract opening into the mouth does not necessarily indicate the tooth of origin of the sinus tract. In order to confirm the etiology, a guttapercha point must be placed through the sinus tract and a periapical X-ray taken. The diagnosis must be verified using a pulp sensitivity test.

Epidemiological studies to evaluate the distribution and frequency of a disease are essential to establish data and define the treatment of a disease which affects a given population and compare it with similar conditions elsewhere in the world. Sadeghi & Dibaei [14] reported 14.7% sinus tract prevalence in a sample of 728 patients referred for endodontic therapy in an Iranian population. Gupta & Hasselgren [5] found 18.1% prevalence in 160 patients studied. However, these epidemiological data contrast with those published by other authors. Mortensen et al. [15] reported a 9% frequency of sinus tract, similar to another study carried out by Miri et al. [16] in another Iranian population where they found a similar prevalence of 9.89%.

In this study, the sinus tract incidence was 15.3% similar to what was reported by Sadeghi [14] and Gupta [5] and almost double the values found by Mortensen [15] and Miri [16]. The difference could be accounted for by the size of the sample as in the studies with the lower prevalence [15,16] the sample size was over 1,500 patients, while in our studies, with a lower incidence, the sample did not exceed 700 evaluated patients.

According to the results of this experience, sinus tract have a direct relationship with chronic apical disease. Similar results have been reported by other authors [5,14,16] and, again, the presence of a radiographically visible apical lesion is directly related to the formation of a sinus tract, and no gender preference has been found.

Various results were found with regard to tooth distribution and patient age. In the results of this study, lower first molars had the highest tendency to sinus tract formation (26.3%) followed by upper central incisors (20%) without any preference in terms of age group. These results agree with the findings by Gupta [5] who found 31% first molar sinus tract and 24% central incisor sinus tract and those of Miri et al. [16] whose incidence in the molar area was significantly higher than in other areas. The authors postulate that as the lower first molar is the first tooth to erupt in the whole dental arch, it could be the most vulnerable to caries and pulp disease. Hence the higher incidence of sinus tract. In contrast with the findings of this study, Sadeghi & Dibaei [14] report a higher incidence rate of this disease in lower anterior teeth in the 10-19 age range. They postulate that the high incidence of anterior tooth dental trauma in the young might be associated with sinus tract prevalence in this younger age group.

Even if at an older age, we found a higher tendency to sinus tract. However, our results did not show any significant differences between the two age groups, as is the experience of other studies [16,17,18]. In chronic periapical disease, pus finds the path of least resistance through the bone, periosteum and mucosa to exteriorize. This is the reason why in the majority of cases, the sinus tract drains out to the facial aspect of teeth and only in a few cases it does so extraorally.

There have been reports of cutaneous sinus tract in the mandibular symphysis involving the lower incisors and in the submandibular region if the first molar is the tooth of origin of the sinus tract or even in the nasal floor when the tooth of origin of the infection is an upper central incisor [3-12,19-21].

Regardless of the point of exteriorization, a sinus tract is a symptom of pulp disease and for it to heal it is essential to identify the diseased tooth, reduce the microbial burden through the appropriate chemical and mechanical preparation and fill the root canal system.

Conclusion

It is essential for a clinician to know the incidence and possible locations of endodontic sinus tract to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment of teeth with pulp disease.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ricardo Macchi for his collaboration in the statistical evaluation of the data. The authors affirm that having no financial affiliation or participation with any commercial organization with a direct financial interest in the matter or materials discussed in this manuscript, there have been no such arrangements in the last three years. The authors deny any conflicts of interest.

References

- Siy RW, Brown RH, Koshy JC, Stal S, Hollier LH (2011) General management considerations in pediatric facial fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 22(4): 1190-1195.

- Osunde OD, Amole IO, Ver-or N, Akhiwu BI, Adebola RA, et al. (2013) Pediatric maxillofacial injuries at a Nigerian teaching hospital: a threeyear review. Niger J Clin Pract 16(2): 149-154.

- Almahdi HM, Higzi MA (2016) Maxillofacial fractures among Sudanese children at Khartoum Dental Teaching Hospital. BMC Res Notes 9: 120.

- Li Z, David O, Li ZB (2014) The use of resorbable plates in association with dental arch stabilization in the treatment of mandibular fractures in children. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 42(5): 548-551.

- Ferreira P, Barbosa J, Amarante J, Insua-Pereira I, Soares C, et al. (2015) Changes in the characteristics of facial fractures in children and adolescents in Portugal 1993-2012. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53(3): 251- 256.

- Macmillan A, Lopez J, Luck JD, Faateh M, Manson P, et al. (2017) How do le fort-type fractures present in a pediatric cohort? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 17(12): 31459-31463.

- Smith DM, Bykowski MR, Cray JJ, Naran S, Rottgers SA, et al. (2013) 215 mandible fractures in 120 children: demographics, treatment, outcomes, and early growth data. Plast Reconst Surg 131(6): 1348-1358.

- Goth S, Sawatari Y, Peleg M (2012) Management of pediatric mandible fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 23(1): 47-56.

- Bobrowski AN, Torriani MA, Sonego CL, Carvalho PHD, Post LK, et al. (2017) Complications associated with the treatment of fractures of the dentate portion of the mandible in paediatric patients: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 46(4): 465-472.

- Yang L, Xu M, Jin X, Xu J, Lu J, et al. (2013) Complications of absorbable fixation in maxillofacial surgery: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 8(6): e67449.

- Rottgers SA, Decesare G, Chao M, Smith DM, Cray JJ, et al. (2011) Outcomes in pediatric facial fractures: early follow-up in 177 children and classification scheme. J Craniofac Surg 22(4): 1260-1265.

© 2018 Dr. Pablo Ensinas. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)