- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy

A New Approach for an Agri-Culture Integrating Science and the Arts

Fritz J Haeni1* and Peter Fischer2

1Former Professor at the University of applied sciences BFH-HAFL, Switzerland

2Former CEO and Director of the Zentrum Paul Klee ZPK, Switzerland

*Corresponding author:Fritz Haeni, Formerly Professor of Plant Pathology and Agroecology at the University of Applied Sciences, School of Agricultural, Forest and Food Sciences BFH-HAFL, CH-3052 Zollikofen, Bern, Switzerland Email: fritz.haeni@bluewin.ch

Submission: January 17, 2020;Published: January 28, 2020

ISSN 2637-7659Volume5 Issue5

Abstract

Agriculture in the art institution “Zentrum Paul Klee” (ZPK) and joint approaches of art and science to address burning problems of our time? Yes, and for many good reasons. The ZPK is explicitly an interdisciplinary art center and in addition to the notion “culture”, art and agriculture share many other interests and concerns, especially in the area of their responsibilities to society and the environment. FRUCHTLAND (Fertile land) was named a project and concept of the ZPK, launched in 2015, for a holistic inter- and transdisciplinary Agri-Culture that is integrative and participatory, integrating science, arts, practical approaches and society.

Keywords:Scientific and artistic research; Integrative sciences and arts; Cultural sustainability; Sustainable agriculture; Agroecosystem; Biodiversity; Ecosystem services; NUS

Introduction

It is only a small step from the artist Paul Klee, who intensively occupied himself with growth in nature, to the Agri-Culture practiced on the grounds of the art center ZPK. The title of the project FRUCHTAND (Fertile Land) refers to Klee’s watercolor “Monument in Fertile Land”. Renzo Piano, the famous architect of the ZPK, did not want a park around the buildings but an agriculturally utilized environment typical for the site. He understood the building and its environment as one unit, as a landscape sculpture which is circumscribed by a steel rail. Since the inauguration in 2005 sustainable agriculture is practiced on the main field of 2.5ha, the biodiversity is supported and the whole ecosystem improved (Figure 1).

Figure 1:The cultivation area is part of the architectural concept of Renzo Piano. In the near foreground, the edge of a nutrient-poor meadow is visible, followed by Oil seed flax and in the background by “Biodiversity Promotion Areas” (BPA) with a very diverse flora and fauna.

Since 2013 the FRUCHTLAND approach has been refined and extended. Models for the farming at the ZPK are highly sustainable farming [1,2] like organic, high level integrated production [3,4] and other sustainable systems such as permaculture. The attempt is to achieve the highest possible degree of sustainability. The products are certified with the label “IPSuisse” of an association of Swiss farmers committed to a sustainable, environment-friendly agriculture. The concept focuses on ecologically oriented farm management practices as well as on biodiversity with measures to encourage “beneficials” (honey and wild bees, butterflies, natural enemies of pests) and hence to improve the ecosystem services. The crop on the main field and the experimental plots are in accordance with a favorable crop rotation and are related to the motto of the year of the project FRUCHTLAND. The aim is to awake public’s awareness for sustainable agriculture and corresponding consumer behavior. The harvested products are available in the museum shop and utilized and presented in the gourmet restaurant Schoengruen, that is part of the ZPK. The trail around the ZPK and within the landscape sculpture discloses interesting perspectives to partly unknown or forgotten crops and to biotopes that may support endangered species such as specific butterflies or native orchids. To achieve this, the aim is a high biodiversity of flora and fauna.

The main field and the experimental plots demonstrate possibilities to improve the ecosystem services and new, creative ideas on sustainable approaches for farming (Figure 2). Together with partners from art, agriculture and society issues are taken up around the values and merits that are closely related to local and global ecosystems and to nature in general (esp. global biosphere). Together with these partners the ZPK is interested in the laws, the beauty and the creative potential of nature and issues such as water pollution, climate change, loss of species and biomass or the availability of sufficient and healthy food for all ‒ worldwide.

Figure 2:Map of the Zentrum Paul Klee: 1. Art Exhibitions. 2. Black Bees (Apis mellifera mellifera) and wild bees. 3. Biotopes for insects. 4. Demonstration plots. 5. Experimental plots. 6. Main field with arable crops, about 2.5ha. 7. FRUCHTLAND (fertile land) - Information panel. 8. Native shrubs (32 species), heaps of branches and stones, extensive meadow. 9. Biotope with stormwood (storm Burglind, 2nd January 2018) / tree guild (elements of permaculture); 10.FRUCHTLAND preview of the year at the entrance of the ZPK: selected plants reflect the motto of the year.

Nature, culture, agriculture

The concept of the project FRUCHTLAND that was finally developed in 2014 and is fully applied since 2015, depicts the analogies between nature, culture and agriculture at levels which are fundamental to the term “culture”, used by farmers and artists alike and therefore highlights the concern for basic values, both material and idealistic [5]. The goal is an integrative and participatory Agri-Culture, which is trying to integrate science, the arts and practical approaches; then analyzing and weighing the various proposals and potential contributions to achieve really sustainable conditions for agriculture and the arts in economic, ecological and social terms.

The concept focuses on responsibility to nature and society, inherent to the arts and land use. As an owner of fertile arable soils (literally “FRUCHTLAND”, i.e. fertile land), the ZPK intends to assume responsibility to use the land in an exemplary manner, i.e. as sustainable as possible and in offering possible models for farmers, urban gardeners, consumers and the general public alike. The intention of the project goes even further: we need to talk about what is possible to achieve by joint approaches of agronomists and artists with inclusion of the general public and show where boundaries occur, and which conflicts may arise.

Partners

For the project FRUCHTLAND, the ZPK has teamed up with partners who are interested in unconventional views and open to holistic, inclusive (inter- and transdisciplinary) and global perspectives. In the project FRUCHTLAND, the ZPK is working with the Bern University of Applied Sciences; School of Agricultural, Forest and Food Sciences (BFH-HAFL). Its former professors Fritz Haeni and Harald Menzi had already developed as advisors on the side of Renzo Piano sustainable land use schemes for the ZPK. Since 2013, Peter Fischer (CEO and director of the ZPK from 2011 to 2016, now independent expert in art) and Fritz Haeni (ZPKadvisor) have jointly developed the new concept of FRUCHTLAND, with the support of Claudia Dähler and Dominik Imhof (ZPK), as well as Christoph Studer and Karin Ruchti (BFH-HAFL). From 2016, the further development and promotion of FRUCHTLAND is provided by Nina Zimmer, the new CEO and Director of the ZPK. Another partner who has been present since the beginning is the Biovision Foundation. Together with its African partners it has developed for Africa appropriate sustainable organic cultivation methods and raises awareness of the consequences of different worldwide consumption patterns. FRUCHTLAND also has several other important partners: IP-Suisse, mellifera.ch, the Restaurant Schoengruen, Hortiplus and Stadtgruen Bern (City Gardens Bern).

Methods

Ecological improvement of the site and monitoring

Figure 3:At the edge of the South hill building and on other sites of the ZPK special biotopes promoting soilnesting wild bees, butterflies and other insects were established.

The biodiversity of the ZPK’s surroundings was increased, promoting and introducing native wild plants. The cultivated plots are surrounded by ecological surfaces, so-called biodiversity promotion areas (BPA), such as wildflower bands or low-nutrient grassland [6]. The total of BPA is 15.7% of the “utilised agricultural area”. For the impact of these BPA surfaces, see [7,8]. Moreover, in the adjacent neighborhood there are sites with forest-like habitats and large surfaces with late mown park-like grassland. In 2015, non-native trees and shrubs of little ecological value and some with unsatisfactory growth have been removed and replaced by native species compliant with the site. Large-growing native trees and an important number of shrub species were added, including species that are hosts for beneficial insects, but excluding species that are relevant hosts of plant diseases. For insects with special requirements in 2016 appropriate biotopes have been set up: For example paving stones surrounded by natural sand or areas with mixtures of sand and some clay for insects such as wild bees needing appropriate niches to lay their eggs in the ground (Figure 3).

Ecological enhancement measures may not necessarily be sophisticated and costly but can often be rather simple

An old fruit tree, that was felled by the storm Burglind on 2nd January 2018, was transformed into a diversified biotope. In front of the south entrance, antlions can be watched, which found their home in a sandy edge away from rain where they dig their crater and sometimes wait for months until prey falls into it. The only thing that was necessary for the development of this precious biotope consisted of removing the pebbles from the surface and to fence it so that it is not trampled. Regular monitoring such as vegetation analyses, soil analyses (including measurement of mesoand macrofauna sounding), surface soil traps (e.g. pitfall traps) was systematically applied at different locations.

Applied farming system

The main field of approximately 2.5 hectares of agricultural land (“utilized agricultural area”) is surrounded by low-nutrient and highly biodiverse grassland (Figure 1). On the main field arable cash crops are grown in a diversified and healthy crop rotation. During the last 15 years the following crops were grown: Winter barley with added secondary flora (3 times); Oil seed rape with early flowering Bird rape on the field border (3 times); Oil flax (once); Triticale with added secondary flora (twice); Sunflower (twice); Corn (twice, with sunflowers on the field border); Winter wheat with added secondary flora (once); Spring oats (once); Spelt (once). Where species and varieties mixtures were appropriate, intercropping (species blends) and cultivar blends were applied, between main crops catch crops. The farming system follows the criteria of a highly sustainable agriculture. This implies that it strives for a high ecological and social performance but is at the same time focusing on a productive and economic result [9-12]. It’s about using the laws of nature in a wise and responsible way, respecting the function of the ecosystems [13]. The objective is to maximize the functional biodiversity (ecosystem services), to

a. protect soils and soil fertility,

b. optimize nutrient flows

c. choose healthy crop rotations,

d. choose resistant crops,

e. choose appropriate mixtures of species and varieties,

f. use undersowings (sown under the main crop) and catch crops.

At the same time, it means to minimize direct plant protection methods (renounce synthetic substances whenever possible), but at the same time also use biological products only with the utmost restraint and in accordance with the risk profile. It has for example certainly to be avoided to “protect” the soil surface against erosion by using a single active ingredient of a total herbicide (e.g. Glyphosate), that is even applied worldwide [14 ]. On the contrary the effect on the whole ecosystem has always to be taken into account, including the preservation of the biodiversity.

Experimental and demonstration plots

The demonstration plots are used to implement and demonstrate the motto of the year and to answer specific questions. For example, in 2015 classical hybrid fodder corn was grown on the main field and, on the other plots, traditional varieties for human consumption as well as a lot of colorful varieties once cultivated by American Indians. An experimental plot has been set up to show e.g. how the Push-Pull- method works in Africa or the Pull-Pushmethod in Europe (cf. chapter “Results”) (Figure 4).

Figure 4:The successful biological Push-Pull method, developed in and for Africa, was demonstrated: The legume Desmodium between the lines of Sorghum bicolor scares away the stem-borer pest insects (Push), suppresses weed and enriches the soil with nitrogen. Brachiaria grass on the border attracts the stem-borer (Pull).

Events

The mission of the project FRUCHTLAND is to bridge the gap between the culture and agriculture, the art and nature. The FRUCHTLAND’s guides and flyers are distributed free of charge to all visitors of the museum [15,16]. FRUCHTLAND’s annual motto (e.g. in 2018 with main crop oil seed rape: “Smallest seeds, great diversity, rich harvest”) corresponds to the grown crops, exemplified ideas on sustainable farming and ecosystem services as well as to the program of art exhibitions. Guided tours on art, nature and agriculture are organized regularly throughout the growing season. An “Agri-Culture-Day” is held five or more times during the vegetation period, with invitees and experts from the art world, applied agriculture, science and politics. Using concrete examples of crops or biodiverse habitats just outside the ZPK building, fundamental questions can be adressed (Figure 5). For example, how a reoriented agriculture will be able to produce enough healthy food, diverse and aesthetically beautiful landscapes, maintain a healthy global ecosystem and make the products available to all human beings. Such fundamental discussions clearly demonstrate the importance of an interdisciplinary and crosssector approach (from art and science to practical agriculture). An intuitive and creative research approach ‒ common in art ‒ can open up new holistic perspectives by complementing the traditional reductionist approaches of the natural sciences. The project FRUCHTLAND considers the food-chain in its entirety, with an emphasis on the passage from “Field to Fork”. The “Agri- Culture-Days” often end with a tasting of delicious dishes prepared by the Restaurant Schoengruen from the crops discussed during a tour around the ZPK. Moreover, the ZPK and its surroundings have a great deal of demonstration objects on sustainable agriculture and an ecologically oriented landscape design. For example, several populations of the original, but endangered native black bees (Apis mellifera mellifera) can be seen in a viewing window near the main hall for art exhibitions (by the way – this is the largest such hall in Switzerland).

Figure 5:“Agri-Culture-Days” and guided tours on art, nature and agriculture are organized throughout the growing season and field trials as well as the development of the biodiversity are analyzed regularly with students, cf. photo (University Neuchatel, CABI, BFH-HAFL).

Results and Discussion

Biodiversity and ecosystem services

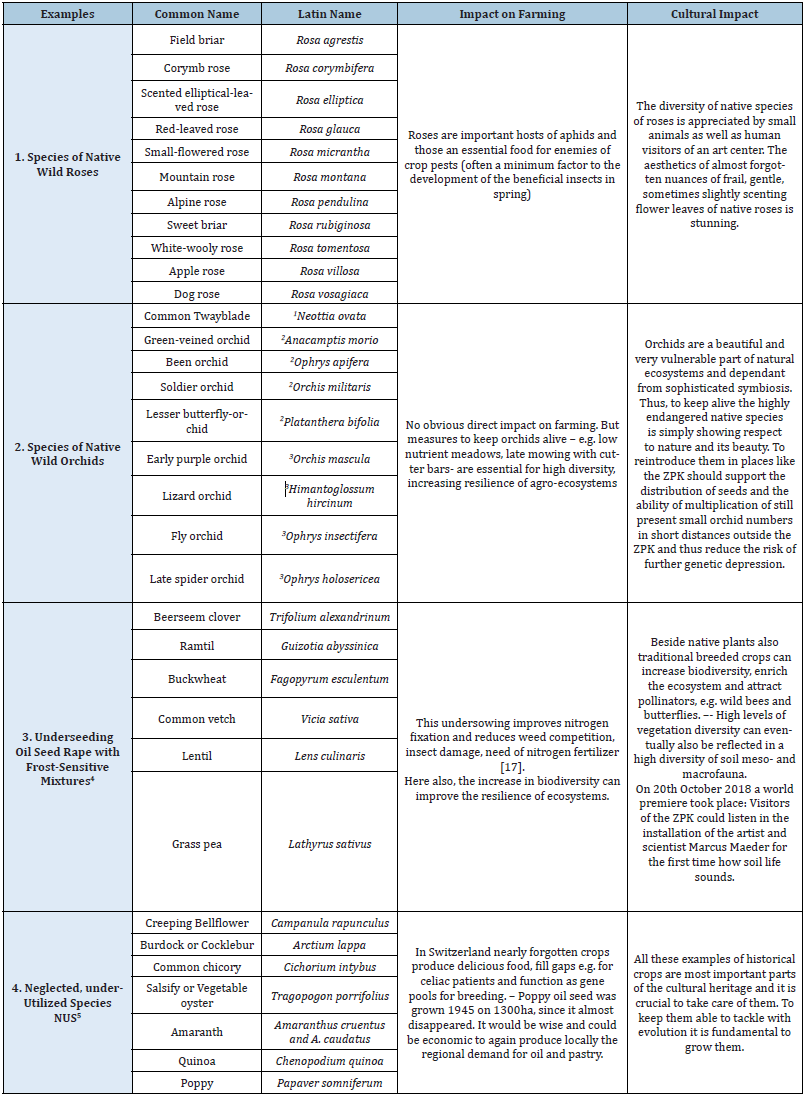

The biodiversity of the ZPK’s surroundings was substantially increased by biodiversity promotion areas (BPA, cf. chapter “Methods”). Nectiferous plants that bloom during the entire growing season are essential for butterflies, honey and wild bees and other pollinator insects. The structural biodiversity was increased by tree and shrub species. On an area where hitherto a monoculture of a single shrub species was prevalent, 32 species of native shrubs including 11 species of wild roses were planted. Diversity has been enriched also with piles of branches and stones (Table 1).

Delicate species, e.g. native orchids are favored by low soil nutrient content (absence of fertilizers) and late mowing of the grass, or even the absence of mowing [21,22]. The ZPK takes part in the master plan for orchid protection in the Kanton Berne, where fifteen orchid species are considered to be most endangered [22,23]. Many of the native orchids, often pioneer plants, are endangered by habitat loss, although all known 76 species are protected throughout Switzerland (all are growing on the soil). In the last 15 years, only 58 species have been detected in the Kanton Berne. In the Bernese Midlands, 40% of them have a high risk of extinction or are already extinct. Orchids are so-called umbrella species. Where they grow thanks to appropriate low-nutrient habitats and symbiosis with mycorrhiza, the biological activity of the soil is often high and also other rare animal and plant species can often be found.

On the ZPK grounds Neottia ovata is still present in a small and rather undisturbed original wood-like habitat. From the reintroduction trial with different endangered species on the ZPK grounds in 2018, Anacamptis morio could post-trial already be detected: Table 1. Establishing again populations of native orchids is a long-term project. But in perhaps two years it will hopefully be possible to show to the visitors of the ZPK the first attractive flowers of reintroduced native orchids. Even more important: the ZPK site is supposed to spread the tiny orchid seeds to the few remaining natural sites outside the ZPK and thus revitalize their populations. Because in most cases the remaining orchid sites are isolated from each other and due to the missing genetic exchange, the small populations of orchids that left over tend to genetic depression and can hardly survive in the long run.

The main beneficiaries of the increased biodiversity and ecological enrichment measures are small animals, especially insects, which account for a number of antagonists of pests, but also birds [7,8,13]. Whereas ecosystem services, especially related to biological pest control, could be improved by appropriate habitat management, late mowing and the absence of fertilizer was also favoring invasive neophytes, which have to be observed and controlled carefully. The eleven native species of wild roses, on the other hand, attract insects. Aphids on roses are in spring the main food of populations of beneficials, such as ladybugs and hoverflies. But the wild roses are not only attractive for insects - they deploy to visitors a whole lot of diversified attractive blooms (Table 1).

Table 1:Increasing the biodiversity by augmenting the number of plant species at the ZPK site.

The regular vegetation analyses at different locations between 2015 and 2019 showed a net increase in the number of species for all locations at the ZPK that were included in the study. This is encouraging, because these are surfaces which were recultivated after the excavations necessary for the construction of the ZPK in 2005. As part of the Sounding Soil project by Marcus Maeder [24], artist and scientist, a recording of the mesofauna and macrofauna (size between 0.2 and about 20mm) shows a very high activity in those soils of the ZPK, that have a highly diverse vegetation. The world premiere of the sound installation [24] took place on October 20, 2018 at the ZPK (Table 1).

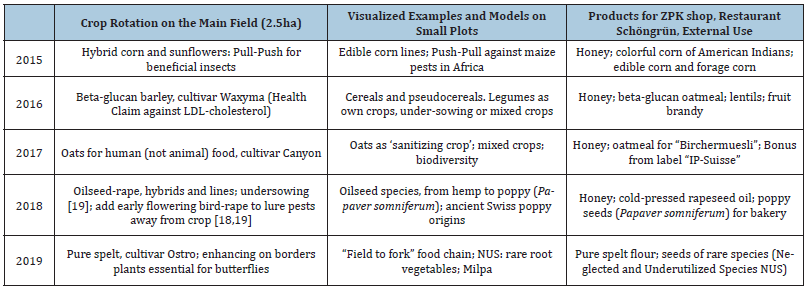

Agricultural products: influence of production on nature and vice versa

The products harvested at the ZPK are certified by the label «IPSuisse » for a sustainable production. New creative approaches will stimulate farmers and urban gardeners for alternative practices that are more sustainable (Table 2). In 2019, the cultivation of Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS, Figure 6) was greatly expanded at the ZPK in collaboration with R. Zollinger [25] of Hortiplus Ltd. A growing interest can be observed to use urban free space for crop production. Families with children as well as interested people from all age classes get active in community, quarter or gardening associations and cooperatively organized groups of farmers and consumers. Their motivation is the realization of holistic ecological, social and economic production and consumption behavior. The participants take responsibility for their action, from seed to fork. The mutual interference between agriculture and free space planning brings new questions and enables new possibilities. In the framework of the “National plan for the sustainable use of plant genetic resources for nutrition and agriculture” [26], the cultivation of NUS and Crop wild relatives (CWR) is supported by the Federal Office for Agriculture. The project “Creeping Bellflower, Cocklebur and Vegetable Oyster” makes lost and forgotten root vegetables available again for private gardens and specialized producers. These rare delicacies will find their place at the family table as well as in specialty gastronomy (Tables 1&2).

For the first time in Europe it was demonstrated in a field plot how the Push-Pull- method is working in Africa. It is a biological method to control both pest insects (African species of corn borers) and the harmful weed striga in corn or also in the more drynessresistant Sorghum bicolor (Figure 4). With an example of Pull-Push (sunflowers on the edge of the fields of corn) was demonstrated how beneficial insects, i.e. the natural enemies of pests, can be fostered in Europe, e.g. in Switzerland (Table 3).

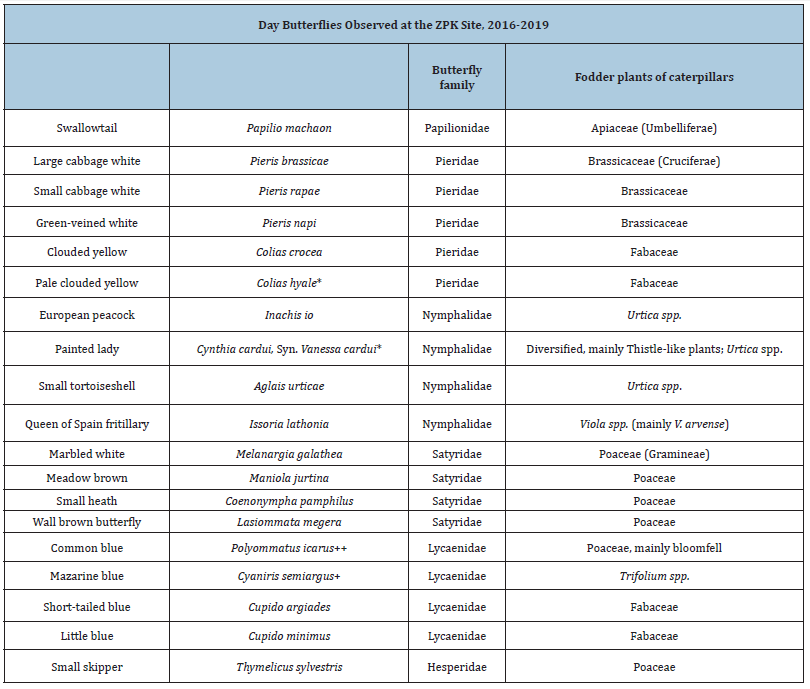

In 2019, we tried to better understand the incidence and behavior of butterflies around the ZPK and their close ties to cereals and secondary flora (Figure 7).

Table 2:Crop rotation, small plots and agricultural products of the ZPK.

Table 3:Butterflies around the Zentrum Paul Klee (ZPK). The host plants are essential for caterpillars (right column) and the presence of flowering nectariferous plants during the whole growing season is essential for adult butterflies. According to [27] in the same metropolitan region of Berne seven other diurnal butterfly species can sometimes be present and twelve other day butterfly species can be occasional visitors [13]. In addition to the more closely observed diurnal butterflies we also observed butterflies of the families Noctuidae, Geometridae, Zygaenidae and Aegeriidae. ++very many; +Many; *Migratory butterflies.

Figure 6:Salsify or “vegetable oyster” (Tragopogon porrifolius) is a Neglected Underutilized Species (NUS) and considered as part of the cultural heritage. It is not only appreciated for the delicious dishes that can be prepared from its roots but also for the beautiful flowers.

Normally the ZPK grounds are frequented by many diurnal butterflies, which from their graceful flight seem to celebrate one side of being, that is the lightness (Figure 8). Around the ZPK between 2016 and 2019 we could regularly observe 19 different diurnal butterfly species. According to the entomological expert Wymann [27] seven more species can sometimes be observed in the metropolitan area of Berne and 12 more species are considered as occasional visitors: These species are described in [13]. Species that are still missing may eventually be favored with specific host plants that will feed their caterpillars (Table 3). However, it would be even more essential to improve the favoring conditions for butterflies also in a broader area [7,8].

Figure 7:If arable pansies (Viola arvensis and V. tricolor) are missing at the edge of the cereal field, certain butterflies, such as the Queen of Spain fritillary Issoria lathonia (Table 3), cannot develop. Many butterflies can coexist with crops and both can benefit from each other. Butterflies are important pollinators and basic for a diverse flora and vice-versa.

Given that butterflies can be considered as bio-indicators same as honeybees and wild bees; it can be concluded that if the butterflies are fine, agriculture is on a good ecological path. However, a proliferation of individual species such as the Painted Lady (Cynthia cardui, Syn. Vanessa cardui) is undesirable, because mass populations of caterpillars can damage crops, e.g. soybeans. The “Agri-culture-Day” of June 29, 2019, was dedicated to butterflies. Whereas the ZPK is usually frequented by lots of butterflies, on this day, unfortunately only few showed up. That was due to the unusually high temperature of 33 degrees Celsius ‒ both quite heavy for visitors and apparently hindering many species of butterflies to fly. How this might be linked with the type of (Agro-) economy could be a theme for a future “Agri-culture day” (Figure 8).

Figure 8:Butterflies can be considered as bio-indicators (cf. text). When different species of the family Lycanidae occur in significant populations, this is a good sign. Here an example of this family, the Common blue (Polyommatus icarus) can be seen at the edge of the South hill building of the ZPK ‒ above the male, below the female.

Conclusion

We have presented a general review of the project FRUCHTLAND (Fertile land) and introduced a new approach for an Agri-Culture that is integrative and participatory, including science, arts, practical approaches and society. A detailed presentation of the concept and important results of the first five years of the project ‒ highlighted from the art and agriculture side ‒ is planned to be published later this year.

Perspectives

As wide an audience as possible should be made aware in an effective but also exciting way of key issues of our time related to nature, culture and agriculture. The visitors of the ZPK are stimulated by different means of the arts as well as science for fundamental questions of today’s life. They are invited to reflect our behavior and to arrive at their own findings and conclusions. For burning problems of our time, such as the threat to the global biosphere, the insect extinction [28,29], the climate change, the needed food for an increasing world population - valuable approaches can be expected, if the different disciplines are acting from their different perspectives, but together in a collaborative way and with mutual respect. The inclusion of all interested and affected persons may allow to take into account all important questions and perspectives. It is to be hoped that the ZPK will continue to provide an important platform and a reflection room for inter- and transdisciplinary approaches including the arts, nature, culture and agriculture and thus contribute to an inclusive and participatory Agri-Culture. May the interdisciplinary center ZPK further be used in a lively way.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the project partners (see text) for their cooperation and support, and specifically Claudia Daehler (2013- 2017, Director facility management ZPK), Dominik Imhof (Head of art mediation ZPK), Urs Rietmann (Head of Creaviva ZPK), Selim Memedi (Facility management ZPK); Ruedi and Kaethi Kraehenbuehl (Land tenants, farmers); Harald Menzi (Saeriswil); Karin Ruchti, Gilbert Delley, Christoph Studer (BFH-HAFL); Andreas Schriber, Sabine Lerch, Hans R. Herren (Biovision); Fritz Rothen, Sandro Rechsteiner (IP-SUISSE); Padruot M. Fried, Stefan Wyss (mellifera.ch); Jonas Steiner (Restaurant Schoengruen); Robert Zollinger (Hortiplus); Rosmarie Kiener (City gardens Berne); Urs Schaffner (CABI); Hans-Peter Wymann (Natural History Museum Berne); Christian Gnaegi (www.weg-punkt.ch); Rafael Schneider (ZHAW-University of Applied Sciences Waedenswil); Simon Spycher (Zurich); Ueli Ochsenbein (Berne); Marcus Maeder ( ZHdK Zurich University of the arts).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Haeni FJ, Pinter L, Herren HR (2008) Sustainable agriculture-from common principles to common practice (2nd edn). INFASA at the Zentrum Paul Klee, Earthprint publ, p. 262.

- Haeni F, Braga F, Staempfli A, Keller T, Fischer M, et al. (2003) RISE, a tool for holistic sustainability assessment at the farm level. IAMA Intern Food & Agric Manag Rev 6(4): 78-90.

- Zihlmann U (2010) Agroscope ART, Integrierter und biologischer Anbau im Vergleich. Resultate aus dem Anbausystemversuch Burgrain 1991 bis 2008, ART-Report 722, pp. 1-16.

- Frick C, Dubois D, Nemecek T, Gaillard G, Tschachtli R ( 2001) Burgrain: Vergleichende Ökobilanz dreier Anbausysteme. (Life cycle assessment of 3 farming systems), Agrarforschung 8(4): 152-157.

- Fischer P (2015) ZPK goes rural-Neuer Schwerpunkt. Bern Kunsteinsicht 6: 16-17.

- Boller EF, Haeni F, Poehling HM (2004) Ecological infrastructures. p. 213.

- Zingg S, Grenz J, Humbert J (2018) Landscape-scale effects of land use intensity on birds and butterflies. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 267: 119-128.

- Zingg S, Ritschard E, Arlettaz J, Humbert JY (2019) Increasing the proportion and quality of land under agri-environment schemes promotes birds and butterflies at the landscape scale. Biological Conservation 231: 39-48.

- Haeni, FJ, Boller E, Keller S (1998) Natural regulation at the farm level. In: Pickett CH, Bugg RL (Eds.), Enhancing Biological Control. University of California Press, Berkeley, USA, pp. 161-210.

- Häni F, Vereijken P (1990) Development of ecosystem-oriented farming. Int Nat Organiz for Biol Control IOBC, Swiss Journal Agric Res 29: 221-436.

- Haeni F, Studer C, Thalmann C, Porsche H, Staempfli A (2008) Massnahmenorientierte Nachhaltigkeitsanalyse landwirtschaftlicher Betriebe RISE (Response-Inducing Sustainability Evaluation), KTBL-Schrift 467, Darmstadt, Germany, p. 94.

- Haeni F, Popow G, Reinhard H, Schwarz A, Voegeli U (2018) Pflanzenschutz im nachhaltigen Ackerbau (9th edn), also in French, Polish, Czech, p. 466.

- Haeni F, Fischer P (2019) Fruchtland-ein Konzept für integrative Agri-Kultur. Agrarforschung Schweiz 10(11-12): 462-467.

- Schönberger A, Vollmer J (2019) Glyphosat-Zahlen, Daten und Fakten. Die Grü

- (2019) Flyer FRUCHTLAND-Fertile land.

- (2018) Guide FRUCHTLAND- Fertile Land.

- Cadoux S, Sauzet G, Valantin M, Pontet C, Champolivier L, et al. (2015) Intercropping frost-sensitive legume crops with winter oilseed rape reduces weed competition, insect damage, and improves nitrogen use efficiency. OCL 22(3).

- Büchi R, Häni FJ, Schenk B, Frei P, Jenzer S (1987) Rübsen (Bird rape) in Raps (oil-seed rape) als Fangpflanzen für Rapsschä Mitteilungen für die Schweizer Landwirtschaft 35: 35-40.

- Terres I (2019) Guide de culture-Colza. Thiverval-Grignon, France.

- Häner R, Schierscher B, Kleijer G, Rometsch S, Holderegger R (2009) Crop wild relatives conservation. Agrarforschung Schweiz 16(6): 204-209.

- Schneider R (2013) Orchid resilience. Pacific Hortic Magaz (Berkeley) 74(4).

- Gnaegi C (2018) Ökologische pflege der verkehrsbegleitflächen im kanton bern und ihre bedeutung für die erhaltung der wildwachsenden orchideen. Orchis, pp. 23-31.

- Gnaegi C (2018) Masterplan protection of orchids, Kanton Berne. Pro Natura.

- Maeder M, Gossner M, Keller A, Neukom M (2019) An acoustic, ecological artistic investigation of soil life. Soundscape, Acoustic Ecology 18: 5-14.

- Zollinger R (2019) Personal communication.

- Federal office for agriculture BLW (2019) National Action Plan (NAP) PGREL.

- Wymann HP (2019) Personal communication.

- Hallmann CA, Sorg M, Jongejans E, Siepel H, Hofland N, et al. (2017) More than 75% decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. Pl0s One 12(10).

- Seibold S, Gossner M, Simons N, Blüthgen N, Müller J, et al. (2019) Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with drivers at landscape level. Nature 574: 671-674.

© 2020 Fritz Haeni. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)