- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy

Critical Analysis of the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) of the FAO: A Case Study of Kuttanad, South India

Mariamma Jacob1, MM Mathew2 and JG Ray3*

1 Associate Professor in Political Science, Assumption Autonomous College, India

2 Associate Professor & Research Guide, Postgraduate and Research Department of Political Science, India

3 Professor of Biosciences, Mahatma Gandhi University, India

*Corresponding author: JG Ray, Professor, School of Biosciences, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam, Kerala, India

Submission: August 03, 2017;Published: September 24, 2018

ISSN: 2637-7659 Volume3 Issue3

Abstract

Kuttanad, the broad below-sea-level polder-farming-system located around the Vembanad Ramsar site is the second globally significant agricultural heritage system (GIAHS) of the FAO in South India. Once, Kuttanad was well known for its rich and traditional indigenous farming practices and the associated high aquatic biodiversity. However, intensive green-revolution practices and regular sewage inflow from the up towns for the past few decades caused the entire wetlands to remain eutrophicated. Continuous application of diverse agrochemicals in the paddy fields and leakage of diesel and engine oil from the intensive operation of tourist diesel-boats in the water bodies results in excessive accumulation of toxic residues in Kuttanad. The fish and other aquatic biodiversity-wealth of Kuttanad are destroyed and the farming remains highly uneconomical. Therefore, the ‘GIAHS’ title of Kuttanad is an opportunity to regain its lost ecological balance. Invitation of global attention to the fact is the principal objective of this investigation.

Keywords: Ecosystem degradation; Agricultural environment; Eutrophication; GIAHS; Kuttanad

Introduction

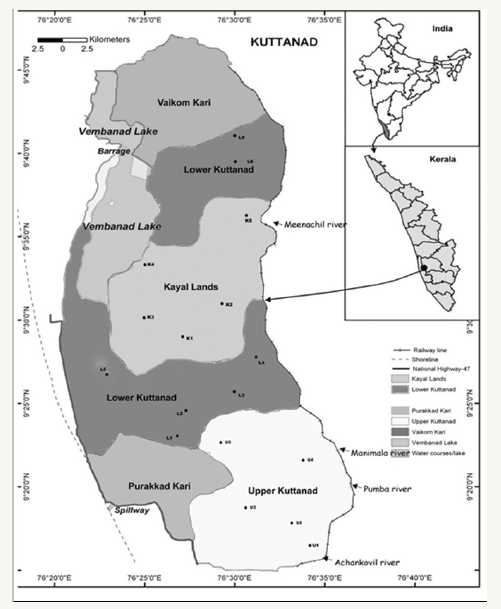

Kuttanad of Alappuzha district, Kerala, South India is now known as a ‘globally important agricultural heritage system’ (GIAHS), the second of its kind in India. The declaration of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) for the GIAHS to Kuttanad came out in a conference held from May 29 to June 1, 2013, at Ishikawa, Japan The Hindu [1]. The declaration was as per a project submitted by the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF) and the government of Kerala in 2011 MSSRF [2]. The GIAHS is a unique scheme of the FAO Koohafkan & Altieri [3], started in 2002 for conserving “remarkable land use system and landscape, which are rich in globally significant biological diversity evolving from the co-adaptation of a community with its environment and its needs and aspirations for sustainable development” FAO [4]. Kuttanad is geographically a unique zone. It is the broad wetland zone situated around the Vembanad Lake system. The region includes ten administrative zones or taluks of the Alappuzha, Pathanamthitta and Kottayam districts. It is mainly the deltaic zone of the major rivers of south Kerala, such as the Achenkovil, Pampa, Manimala and Meenachil. In the past, the marshy soil in this zone was regularly enriched by deposit of a tremendous amount of silt through the river systems of the region in the monsoon season. The clayey paddy soil in the area remained highly fertile and very suitable for paddy cultivation. However, few decades of deforestation in the watershed areas of the rivers and the fast-growing urbanization along the course of these rivers have caused a change in the regular ecological replenishment of the soil systems of Kuttanad. Historically, the ‘Kuttanad’ is a land of great traditions, which has the reference in the early Tamil literature, like Venpai and Tholkappiyom. In such books, the mention on Kuttanad appears as 12 Nadus (principalities) where the people spoke quite ancient Tamil language. Even today, the relics of the pretty old Tamil inscriptions are visible on the wall paintings of certain temples and churches in the region, especially those on the altars of the St George’s Forane Church, Edathua. Kuttanad was the principal ‘rice-bowl’ in the former princely State of Travancore as well. Kuttanad is the land reclaimed from the waters at different periods in history.

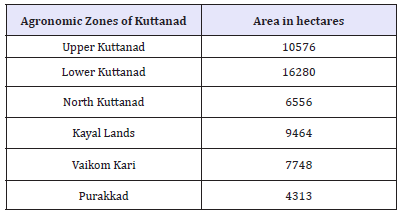

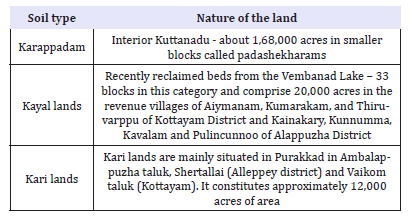

It is entirely accurate to say that “God created the earth and the waters, people created Kuttanad by raising it from the waters” Pillai [5]. In the early periods, Kuttanad was described as a broad area of about 66870.5 hectares of wetlands of Kerala under paddy cultivation Velupillai [6], extending from Kollam in the north up to Ponnani in the south. As per the Travancore State Manual, Kuttanad included twenty sovereign territories, twelve in Ampalapuzha, four in Kottayam, three in Changanacherry and three in Ettumanur Nag- am Aiya [7]. However, Kuttanad later came to represent only a few areas in the Kottayam, Alappuzha and Pathanamthitta districts. The boundaries of Kuttanad include the Thannermukkam barrage in the north, the Thottappally spillway in the south, the Main Central road in the east and the National Highway-47 in the west. The present Kuttanad wetland zone includes Ampalapuzha and parts of Karthikappally, Shertallai, Mavelikara taluks of Alappuzha district; Chengannur and Thiruvalla taluks of Pathanamthitta district and parts of Changanasseny, Kottayam and Vaikom taluks of Kottayam district. The land currently includes about 54935 hectares of paddy fields belonging to six agronomic zones (Table 1) and three distinct soil types (Table 2). But in the political map of the present state of Kerala, the name Kuttanad is ascribed just to a taluk known as Kuttanad taluk in the Alappuzha district. Therefore, the boundary of the GIAHS conferred to Kuttanad is quite confusing.

Table 1:The major agronomic zones of present Kuttanad.

Table 2:Major soil types of Kuttanad.

The primary goals of the GIAHS include the creation of public awareness on traditionally critical agricultural systems in the world. The GIAHS title enables a better global understanding and appreciation of unique farming practices followed in local and tribal communities, in different parts of the world. Documentation of such indigenous knowledge is considered quite essential to the promotion of traditional agricultural practice at global scales as a measure of regaining the missing components of agricultural sustainability in the world. Sustainable agrarian exercise is essential to global food security and global sustainable development. The programmed of the GIAHS is also a measure for attaining food security at regional levels as well. Such goals are fulfilled through an extension of various kinds of support to the local population in their sustainable agricultural efforts, which also include the provision of Eco-labeling for better marketing of their green agrarian products. Measures to ensure the promotion of ecotourism is an essential component of the project. The principal intention of the FAO in this scheme is to support countries in eradicating poverty, loss of livelihood and to improve the economic status of the poor and marginalised people in traditional agricultural regions in the world. This programme is also viewed as a global measure of sustainability against increasing population pressures, environmental degradation, and biodiversity erosion in the world, which may arise in the future. The FAO also considers this as an opportunity for the world to achieve its millennium development goals (MDGs). Moreover, every selected site of the GIAHS is expected to be places of high agricultural and the associated biological biodiversity, which are currently facing specific management crisis Koohafkan & Altieri [3]. However, the GIAHS title conferred on Kuttanad doesn’t involve a clear-cut programme of Eco-restoration and the region remains contradictory to the goals of the FAO as per the concept of the GIAHS. Therefore, a critical analysis of the GIAHS status given to Kuttanad has become inevitable to assess the success of such a global measure for environmental sustainability of unique farming zones in the world. The attempt is to expose the immediate environmental problem-solving measures required in Kuttanad for attaining the goals of FAO as per its norms for the GIAHS title to a place.

Methodology

The present investigation is based on field observations, an opinion survey of local people and a comprehensive review of the available literature on the history of diverse developmental activities in Kuttanad during different periods. The field observations and opinion survey to assess the current environmental status of the region was carried out from January 2015 to January 2017. Although the developmental and environmental issues of Kuttanad are already well investigated by many national and international experts, both individually and collectively, a clear-cut suggestion to regain its lost ecological balance has not yet been identified. The present attempt was to critically analyse the heritage characteristics of the Kuttanad farming practices and the current environmental status as well as the opinion of people on the same. Another focus of the investigation was on analysing how far the current environmental issues in the ‘Kuttanad’ will enable the region to fulfil the FAO criteria of the GIAHS. It also discusses the significant hurdles, which the area must overcome in achieving and retaining this global title as a model for excellence in environmental management of an agricultural wetland.

Results and Discussion

The uniqueness of kuttanad

Review of the literature reveals that the two sites already identified in India as the GIAHS are ‘Koraput’ in Odisha State and ‘Kuttanadu’ in Kerala state. The New Indian Express [8]. The first site, Koraput is a pure tribal zone, where shifting cultivation, is currently practised. The place is still maintaining its rich agricultural biodiversity. Tribal farmers cultivate there, even today, several traditional varieties of paddy, millets, pulses, oilseeds and vegetables. How ever, the site is affected by excessive deforestation, soil erosion, soil degradation and habitat loss. The people in Koraput are affected by poverty, illiteracy, large families and small farm holdings. Therefore, the effort is direct support to the tribal farming community to continue their current agricultural practices, which include provision of better land protection schemes, seed preservation techniques, afforestation for soil fertility management and the like.

On the contrary, no traditional variety of rice is currently cultivated in Kuttanad. Moreover, a comprehensive community restoration programme is not included in the GIAHS scheme of Kuttanad. Compared to Koraput, Kuttanad is a different agricultural zone in the country. It is a wetland system, once well known for its traditional farming practices, fertile soils, traditional varieties, high productivity and the associated very high aquatic biodiversity. Of course, it is still the only below-sea-level paddy-farming system in Asia. But unlike Koraput, which is a tribal-land, Kuttanad remains a modern and complex agro-economic zone, where the general population are socially and culturally elite.

The ecological uniqueness of kuttanad

In the literature, there is an increasing amount of evidence on the socioeconomic and ecological uniqueness of Kuttanad. The Kuttanad paddy fields are reclaimed marshlands of the Vembanad wetland system. Reclamation of the lands was carried out in the last few hundred years by traditional enterprising farmers with the support of committed labourers. In the past, the Vembanad wetland system had supported different livelihoods to diverse ethnic communities such as those who are engaged in fishing, mussel harvesting, coconut farming, toddy extraction, traditional crafts of weaving baskets and mats using the dried leaves of Pandanus, preparation of thatching materials using coconut fronds, and the like Kamalasanan [9]. It was the conventional rice bowl of Kerala, where below sea-level paddy farming had been practised for the last two hundred years until the green-revolution measures were introduced in the 1960s.

The tragic side of the uniqueness of the current Kuttanad is that most of those traditions are not found now in the zone, except the below-sea-level rice farming. The entire Kuttanad is now transformed into ‘green-revolution’ fields. The present Kuttanad is a live demonstration of the catastrophic environmental impacts of the ‘green-revolution’. The whole Kuttanad wetland paddy ecosystem, once famous as the rice bowl of Kerala, has now become degraded into a real ‘tear bowl’ of farmers. Farming has become uneconomic. The ill-ecological green revolution farming practices have now turned the entire region into a highly polluted farmland of water-borne and other environmental diseases including cancer due to the accumulated waste and toxic residues.

The significant challenges in kuttanad for retaining the GIAHS title

While considering the GIAHS status as a real recognition of its traditional and indigenous farming practices, the declaration also places many challenges as well. As per the GIAHS norms, there should be proper documentation of the traditional knowledge of under-water paddy cultivation in the zone. The region requires appropriate conservation programmers to preserve the associated aquatic biodiversity in the wetlands. Besides that, there should be capacity building programmers for farmers to practice sustainable agriculture. Farmers need to be equipped for acquiring Eco-labels for better marketing of organic farm products if they generate such organic farm products in the zone. However, the complex socioeconomic and environmental conditions in the region pose real challenges to such noble goals. Critical analyses of such problems reveal the specific difficulties currently existing in the area for the region to achieve and maintain the high aspirations of the GIAHS title as per the FAO norms.

The agricultural heritage of kuttanad

Kuttanad is a unique place of rich agricultural heritage, natural beauty and innovative people. The agrarian culture of Kuttanad may be divided into three specific phases such as the traditional phase (the ancient period up to 1850s), pre-modern phase (1850- 1940s) and the current green revolution phase (1940 – to the present time).

In the traditional phase, agricultural practices in Kuttanad were in good harmony with nature. The land remained less populated, and the paddy cultivation was quite meagre, limited to the upper reaches of the area. Cash economy was wholly absent. In those days even, barter system was quite nominal because people had no surplus and there were no shops and markets not only in Kuttanad but throughout Kerala Ward & Connor [10]. According to the same authors, in those days, the labour class remained very poor in the society. Agriculture labourers were bought and sold at a price not much higher than that of cattle. There prevailed landlord (Janmi) system, and landlord’s role was just to handover the specified quantity of seeds to the land-worker caste, the ‘Pulayan’.

In the ancient period in Kuttanad, rice-fallow-rice or rice-fallow- fallow was the cropping pattern in Kuttanad, which may be viewed as an extension of an ancient form of tribal farming known as ‘Punam Krishi’. In the early part of 20th century, even in 1916, the ‘Punja’ lands of Kuttanad were cultivated only once in two years Kamalasanan [9]. According to the same author, cultivated land in that period in Kuttanad was relatively abundant, the availability of labourers was quite scarce and only limited plots were cultivated. Many fields were often allowed to remain fallow during specific periods by water let in. Till the construction of the Thannirmukkam barrage in the 1950s, because of the position of the land below the mean sea level, when the freshwater level recedes in the summer the Kuttanad ‘Punja fields’ were regularly inundated by saline seawater. In the pre-modern period, Kuttanad witnessed immigration of a considerable number of enterprising farmers into the zone. Advancement in paddy cultivation began quite extensively, but the cultivation practices were in the traditional way Nagam-Aiya [4]. According to this author, the traditional indigenous paddy varieties of a more extended gestation period, of about 4-5 months, taller varieties viz. Champavu, Karuthachara, and Attikarai were cultivated in Kuttanad in those times.

In the ancient cultivation programme, until the beginning of the green revolution programme in Kuttanad in the 1960s Kurien [11], there were no permanent bunds around the polders. Cheap and locally available materials like coconut leaves, twigs of trees, straw, shrubs, reeds and clay were used for mud-bunding to create polders in the waterlogged wetlands. The mud-bunding operation was highly labour intensive and time-consuming. After the mud-bund construction, large water wheels (chakram) were used to de-water the fields. The ‘chackrams’ varying from four to thirty-two leaves or spokes were in use in Kuttanad, which was a ‘day and night task’ and was done on a work shift. Sowing was always done before the month of Makaram (a month of Malayalam Era equivalent to October- November) for fear that ‘makarakal’, a specific climatic issue would ruin the entire sprouted plant. Harvesting was always completed before ‘Meenam-Medam’ months (March - April). Attack of the pest was managed in Eco-friendly ways. Caterpillars of the insects were collected using a basket sweep (puzhukkotta or pookkotta) and destroyed.

The third phase of intensive agriculture began in the region in the post independent period. In this period, the area witnessed extensive human modifications of its environment to overcome the limitations imposed by nature Pillai & Panikar [12]. According to this author, land reclamation became an integral feature of Kuttanad in the period. While reclamation was confined to the shallow upper reaches of Kuttanad in the pre-modern periods, it got extended to the deep-water zones of the lake in the post-independent modern period. The increased demand due to population pressure and sudden rise in paddy price in the post second world-war period and the depletion of shallow backwaters led to the new reclamations of the deep water of the Vembanad Lake. These reclamation efforts received ample support from the government in the form of interest-free loans Kerala Sastra Sahithya Parishad [13] and exemption from tax for a short duration Pillai & Panikar [12]. This reclaimed land represented the significant portion of ‘Kuttanadan Punja’ in the second half of 19th century.

Although the introduction of pumping engine with ‘petty and para’ began in 1912 Aravindakshan & Joseph, [14], it became common, only in the 1940s in Kuttanad fields. Mechanization fastened the ‘Kayal’ reclamations and changed the entire face of paddy cultivation in Kuttanad. The mechanical pump enabled reclamation of large blocks of hundreds or thousands of acres. Originally, steam engines were used for pumping out the water from the polders for cultivation. Later kerosene engines arrived during the time of the first world-war, followed by diesel engines and finally electric pumps. By 1945, nearly 20000 acres of Vembanad Lake were brought under cultivation Pillai & Panikar [12]. According to this author, the peculiarity of reclamation in Kuttanad is that it was mainly carried out by private farmers and it stands as a ‘classic example of entrepreneurial innovation’. In 1940 the above rice-fallow- rice pattern of cultivation was banned, because of the world war and the consequent fall in the incoming of rice from Burma. To prevent salt water incursion and flood and to facilitate two crops in a year, construction of engineering structures like Thottappally Spillway (construction began in 1951) and the Thannermukkam barrage (construction began in 1955) were also carried out.

The traditional agricultural practices

The rice cultivation system in Kuttanad was unique. The farming practice in the region has a tradition of more than 150 years. These were developed locally by the farmers of the region. Octogenarian farmers of the area still remember the ancient practices in Kuttanad. According to a traditional farmer by name Joseph, ‘the major aspect of the traditional farming was that it was ecologically based’. Farming operations were entirely related to the local water cycle in the region. Fields were sown at the beginning of the northeast monsoon, and the harvest was completed before the onset of the southwest monsoon. Accordingly, there was only a single crop in a year. Soil fertility was dependent on natural cycles, and fertiliser applications were entirely organic and low, just as per the need. No chemical applications were followed in the zone. To permit the soil to regain its natural fertility, the paddy fields were kept fallow between successive crops. Annual saltwater incursions were not only permitted but considered essential to the soil fertility management as well as the ecosystem balance and biodiversity conservation in the area. The cultivated varieties were purely native, quite adapted to the ecological regimes of the zone and less manure demanding. Mechanized tillage operations were not at all carried out in the place. Although, these traditional agricultural practices have almost become extinct and the old paddy varieties are no more available in the area, looking back to the Eco-friendly heritage farming is necessary to regain sustainability in agriculture in the zone and essential to the achievement of GIAHS status in Kuttanad.

The traditional indigenous knowledge, which was quite dynamic, has great value, because it stands as the information base of the society, not only locally, but significant to the global community. Therefore, the government needs to extend liberal economic support for Kuttanad farmers in their transformation of the present farming practices in the region back to a sustainable method by applying the traditional knowledge of the ancient farming community.

The major environmental changes

In the modern period, the Kuttanad witnessed the emergence of capitalist farming. As a result, the attitude of farmers towards agriculture began to change. New reclamation of 20,000 acres caused the creation of surplus equal to a total increase of 89.86 per cent of the net yield from the area Aravindakshan & Joseph [14]. Farmers became interested in producing more than what they required. Introduction of money wages began in this period. There was a considerable demand for rice in the state due to the general socioeconomic and political situations in the world.

As the demand for better varieties of seeds that suit ‘Punja’ cultivation in Kuttanad increased, a Plant Breeding Station was established at Moncompu in 1940 under the auspices of the then Imperial Council of Agricultural Research. It released the first varieties for Kuttanad, the MO.l (Chettivirippu) and the M0.2 (Kallada Champavu) in 1945. The emergence of capitalist farming in Kuttanad initiated changes in the agrarian relations. Tensions arose between farmers and labourers. The trade union movements originated in Kuttanad in this period. It caused significant changes in the traditional relationship between farmers and the labour class Pillai & Panikar [12].

The ‘Green Revolution’ strategy, which began in the zone in the 1960s, caused significant changes in the region Kurien [10]. Mechanization of certain farming operations such as tractor tillage was also initiated in Kuttanad in the modern period. The period also witnessed governmental interventions like research, extension activities and the like in the region. Changes in practices occurred mainly in the selection of High Yielding seed varieties (HYV) for cultivation and the application of fertiliser and plant protection chemicals. The percentage of farmers who adopted HYVs was about three fourths in the zone Joseph [15]. Per hectare consumption of fertilisers had increased from 61 kg in 1961-62 to 190 kg in 1968- 69 periods Tharamangalam [16]. Only six per cent of the farmers carefully followed the fertiliser recommendation Joseph et al. [15], whereas the rest applied more than what was needed.

Because of green revolution efforts, towards the middle of the modern period, especially from the 1980s onward, the region started facing severe eco-catastrophe such as widespread occurrence of water pollution, eutrophication and biodiversity erosion. A Lot of social changes also occurred in this period in Kuttanad. Agriculture became highly uneconomical and the environment highly toxic and unhealthy due to the accumulation of toxic residues in waters, sediments and food. Such a worsening in environmental conditions in Kuttanad led to an exodus of well-to-do farmers from the zone.

The major socioeconomic changes

In the past few decades, paddy cultivation has become highly uneconomical in Kuttanad. The cost of cultivation has increased tremendously. The required labour force has become scanty, and the cost of labour has become quite high. Many of the enterprising farmers have left the place, and their fields are either remaining fallow or are given to others on a lease. As per a research estimate, only 60 % of the paddy fields in Kuttanad are cultivated now, and about 11% of the land remains as cultivable wastelands, whereas the others continue fallow Maniyosai & Kuruvilla [17]. According to farmers in the region, leasing of land in Kuttanad began officially in 1974 by the state government itself, who took over the ‘Kayal lands’ as ‘excessive land with farmers’ and leased out the same, at a scale of 5 acres each to small-scale farmers (at a rate of Rs.120 per acre).

The present investigations revealed that currently, a new system of tenancy has emerged in the region. As per a rough estimate, more than 50 per cent of the paddy cultivation in Kuttanad is carried out on leased land. Farming on the lease has its ecological impact. Those who cultivate on leased land are least interested in land protection methods or environmental stability but are focusing on the maximum yield at any cost in each crop season. Overall, the agricultural production in the region is declined by 9%, paddy has become non-remunerative, 80% of the coconut palms remain diseased and about 50% of the families survive below the poverty line in Kuttanad Harikumar [18].

Increasing of the labour cost and insufficiency of the labour force has caused escalating dependency on mechanised farming practices such as tractor tillage and machine harvest, which have aggravated the issue of soil degradation in the region. Traditional soil management and tillage operations are forgotten and have become highly uneconomical as well. Untimely or unnecessary and unscientific mechanized tillage is causing a colossal amount of clayey topsoil to get dissolved in water and to pump out into the streams. A general survey revealed that the current ill-ecological farming practices are aggravating soil as well as general water degradation in the Kuttanad farming zones. The unscrupulous application of chemical fertilisers and plant protection chemicals are contaminating the cultivated fields and the entire wetland. The areas, which are not cultivated, have become too weedy. It has become highly uneconomical for cultivation to be regained in such abandoned fields. Overall the socioeconomic situation has changed in the region. There are not enough people and resources to manage ecological farming in this once highly productive Kuttanad wetland, the traditional ‘rice bowl’ of Kerala.

The major environmental challenges

As the waterlogged, wetland paddy zone, the primary environmental challenge in Kuttanad is that of water pollution. The general belief of people in the region is that dilution is the solution of all contamination. Flowing water is considered the best way to carry away waste to dilution. Therefore, people throw away all organic and other waste into water bodies. Improper sanitation also contaminates the water. Apart from the degradable waste, lot of plastic waste materials is also seen accumulated all over the waterways in Kuttanad. Lack of waste management systems along the rivers in the upstream regions also causes flowing down of the entire waste of all those towns to reach Kuttanad regularly. As a result, the entire Kuttanad now remains the waste-basket of central Kerala.

In addition to these wastes, a significant share of the excessively applied fertiliser and the other plant protective chemicals leach out to the water and soil in the region. Agricultural leaching out for decades has been causing the entire pool to remain eutrophicated and toxic. The construction of Thannirmukkam barrage has aggravated the nutrient accumulation and the associated weed growth in the Kuttanad waters. Fish biodiversity is almost destroyed. No systematic account of the diversity of aquatic flora, including the planktonic algal wealth is carried out in the region. Accumulation of toxic residues and bacterial contamination has caused practical absence of drinkable freshwater in the entire zone. People are suffering from dreadful skin and other diseases, including cancer. On the other hand, because of lack of proper management of soil fertility, the entire productive wetland soils are getting depleted of specific nutrients to support paddy farming. The coconut crop in the region is also destroyed by the root-wilt disease. The overall impact of these environmental challenges in Kuttanad is tremendous, including severe water, land and biodiversity degenerations, which severely affect the health of people living there.

The major ecological option

The primary ecological options in front of the Kuttanad farming society today is whether to return to traditions of the ancient period (its heritage) as per the GIAHS norms or to continue the current farming practices. The pathetic side of the current situation is that the region has changed so much so that a return to its traditional socioeconomic or agricultural practices seems quite impossible. However, the area must follow sustainable agriculture practices, which ensure productivity, environmental stability and biodiversity conservation. Design of such a farming system to ensure sustainability in this highly degraded and ecologically sensitive wetland cultivation zone is the herculean task ahead to achieve the GIAHS of Kuttanad.

The major tasks to retain the GIAHS title

As per the GIAHS norms Koohafkan & Altieri [3], the region must become a universal store of indigenous knowledge for the benefit of the whole world now and for future. The conservation of agriculture in the zone is expected to display a model, useful for others in their land improvement in the future. It must become a model for management of agro-ecosystems elsewhere in the world. Therefore, the farming practices in the region must become more bio-diverse, local, resilient, sustainable and socially just. Moreover, the improvements in agricultural methods to be made in the area must become beneficial to the local as well as the global community. Kuttanad must become a repository of valuable resources for climate adaptation, quite useful to the whole world. It must become a model for preparedness for climate change, especially for coastal wetlands of the entire world. However, it is quite evident that Kuttanad at its current pathetic ecological collapse will not be able to offer such heritage functions anymore without comprehensive Eco-restoration and environmental education programmes in the region.

Although, the MSSRF had submitted a master plan to revitalise the Kuttanad farming system under the label ‘Revitalization of Kuttanad Heritage Agricultural Zone’, it appears from MSSRF project report that no comprehensive plan of the rebuilding of the ecosystem is included in the project. Apart from the beginning of an international institute in Alapuzha for research and training in a ‘below sea-level farming system’, no serious planning of rebuilding is taken up under the GIAHS financial support. The Hindu [19] moreover, the FAO grant of US $30,000 is quite insufficient to manage the herculean task ahead of the ‘revitalization programme’ of this heritage zone. Even after the implementation of a multi-crore Kuttanad Package with the financial support of the Central Government, the region remains the same without any positive change towards environmental sustainability. Clear cut action plans, definite administrative authorities, along with proportionate national budgetary allocation are the immediate requirements to achieve the same. Although the state government is a participant in the project submission, no commitment is yet shown on the part of the state government or the central government in fulfilling the task ahead as per the GIAHS.

Findings of the opinion survey

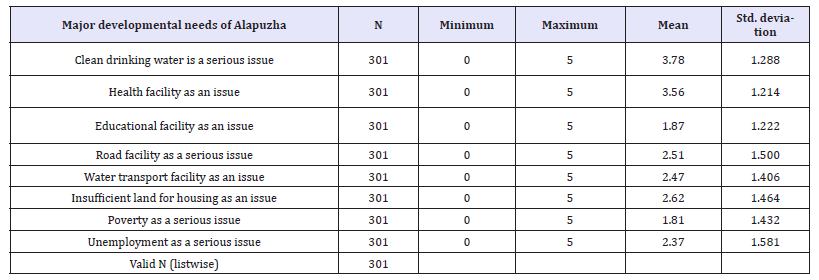

To ascertain the social feeling regarding the status of socioeconomic development of Kuttanad, eight major issues were presented to them to express their views as per a score scale of 0-5 (Table 3). It may be noted that the two crucial developmental issues, which are still affecting people in Kuttanad as per the average score given to the issues remain ‘Drinking Water availability’ (3.78) and ‘health amenities’ (3.56). At the same time, the issues such as the need of land availability for housing, road availability, and better water transport and more employment opportunities remain significant issues still today with scores of 2.62, 2.51, 2.47 and 2.37 respectively. However, the developmental issues such as the need for better educational facility and poverty alleviation programmes remain the least significant issues in Kuttanad with scores of 1.87 and 1.81 respectively. The preference of people for roads over water transport in the waterlogged Kuttanad reveals the ecological ignorance of people, because the construction of roads, which often causes reclamation and the consequent blocking of waterways, is not an environmentally feasible developmental activity in the area.

Table 3:Response of people regarding the major unsolved developmental issue in Alapuzha.

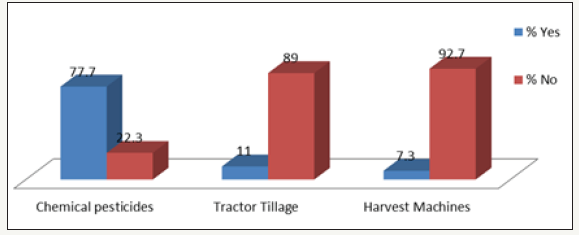

To ascertain the feeling of people regarding the environmental impact of the ‘green revolution agriculture, three specific queries on whether the three important components of the green revolution in Kuttanad such as ‘chemicalised’ farming practices, tractor tillage and use of harvest machines have created serious adverse environmental impacts in the region. Most people believe that mechanization in agriculture such as the harvest machines and tractor tillage (92.7 and 89.0 % of people respectively) have created no adverse impact in the region (Figure 1). On the contrary, most of the people (77.7%) believe agrochemicals (fertilizers and pesticides) have created serious environmental impact in the region.

Figure 1:Map showing the ‘Greater Kuttanadu’ zone.

Figure 2:% of people in Kuttanad who believe whether the three different green revolution activities have created high adverse environment impact in the region.

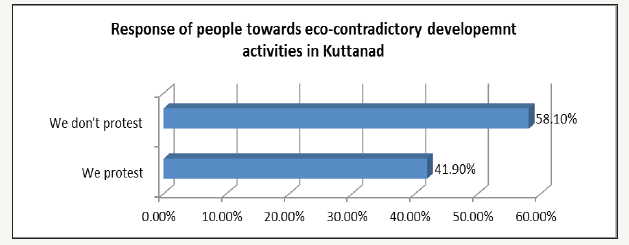

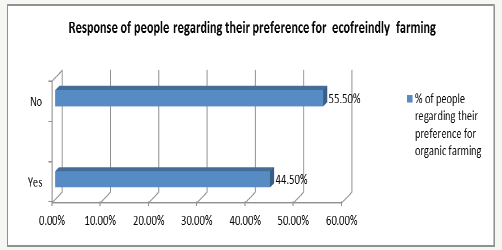

To ascertain whether they prefer to any change in the current Eco-contradictory farming practices in the zone, two specific queries such as whether they protest the application of chemical fertilizers or pesticides and whether they opt for organic farming in the region were made. It may be noted that not only most people do not resist the eco-contradictory developmental initiatives in Kuttanad, 55.5% of people in this region still prefer chemicalized farming over the organic farming (Figure 2-4).

Figure 3:% of people who protest the application of chemicalized farming in Kuttanad.

Figure 4:% of people in Kuttanad who prefer organic farming over chemicalized farming.

The major possibilities

The present field observations and opinion survey revealed that immediate expert attention is needed for overcoming the extreme environmental and socioeconomic challenges that currently exist in Kuttanad for its recognition as a global model for unique farming. The FAO sanction of the GIAHS title to any region without a comprehensive account of the current socioeconomic and ecological understanding of the region and assured commitment of the authorities concerned will cause erosion of faith in UN institutions such as the FAO as well as the global recognition of a nation involved.

Therefore, the following are the possibilities for the attention of the country as well as the FAO. The state can form a ‘Grater Kuttanad Development Authority’ to plan, implement and monitor the ecological rebuilding or restoration of the entire Kuttanad wetlands of Kerala. There should be a time-bound scheme of organic farming of traditional paddy varieties in the whole Kuttanad wetland fields. To achieve the goals, the state shall have a definite plan of environment education in Kuttanad. The entire farmers need conviction about the importance of sustainable ecological practices against the existing chemicalized practices. For the convenience of state-controlled ecological farming operations, the entire Kuttanad paddy fields may be grouped into few paddy cultivation cooperatives or companies (Kari, Kayal and Karappadam cooperatives) of farmers having exchangeable shares equivalent to their share of land in the region. The government needs to acquire the entire uncultivated wastelands in the area and utilize the same for massive mangrove afforestation in the zone; at least 50% of the wastelands need to be planted by mangrove species, which would be an important measure for regaining the lost ecological balance of this coastal wetland zone. There should be massive cleaning up activities in the entire Kuttanad region. The state shall implement comprehensive water treatment plants in all the small and big towns along the cost of the rivers so that untreated sewage will not flow down to the region. The FAO may ensure that the Government of India initiate and liberally finance a comprehensive programme of revamping the ecological health of the entire Kuttanad zone, just because they have agreed to the recognition of Kuttanad as a GIAHS as per an international agreement.

Conclusion

The current environment status of Kuttanad, an already identified GIAHS of the FAO is an important evidence for the organization to review its concept and practice of conferring such titles to any agricultural zone in the world. The FAO recognition of the GIAH status to Kuttanad is also an opportunity for the nation to rebuild one of its ecologically most vulnerable wetland zones in the country with global support. However, significant challenges that remain ahead in this target need to be correctly identified and quantified immediately. A proper designing of the specific action plan of comprehensive Eco-restoration is inevitable to the success of the scheme. Appropriate administrative authorities need to be constituted for the correct implementation and constant monitoring of the project. Since Kuttanad ecosystem is a complex socio-economic and ecologically quite a vulnerable system, intensive environment education programme is highly essential for people in the zone, especially for the success of this project. The unique scenic beauty of the region also offers an opportunity for economic prosperity to the nation through exploration of attaining a definite space in the global tourism map of the world. Kuttanad has the potential to become a model place of preparedness for global warming impacts in the coastal planes. If this opportunity is ignored, this ecologically spoiled but culturally rich zone of high biological potential may be lost to humanity forever.

References

- The Hindu (2013) The global focus on the Kuttanad, The Hindu Daily

- MSSRF (2016) Conserving Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Sites (GIAHS), MSSRF data.

- Koohafkan P, Altieri MA (2011) Globally important agricultural heritage systems, A legacy for the future. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- FAO (2002) Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS), Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nation.

- Pillai R (1974) My native place one hundred and fifty years ago. Leo XNI Library Souvenir, Champakulam.

- Velupillai TK (1940) The travancore state manual. Kerala Gazetteers Department, Thiruvananthapuram, India.

- Nagam AV (1906) Travancore (Princely State). The travancore state manual, Travancore government Press, India.

- The New India Express (2012) Kuttanad the second GIAHS in the country, The New Indian Express Daily.

- Kamalasanan NK (1993) Kuttanad and agricultural labour movement. DC Books. Kottayam, India.

- Ward BS, Conner PE (1863) Memoir of the survey of the Travancore and Cochin States 1&2. Government of Kerala, Gazetteers Department, Thiruvananthapuram, India.

- Kurien CT (1982) Agricultural change - A comparison of Tamil Nadu and Kerala. In: PP Pillai (Ed.), Agricultural development in Kerala. Agricole Publishing Company, New Delhi, India.

- Pillai VR, Panikar PGK (1965) Land reclamation in Kerala. Asia Publishing House.

- Kerala Sastra Sahithya Parishad (1992) Kuttanad, myth and reality. Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishad Publication, Thiruvananthapuram, India.

- Aravindakshan M, Joseph CA (1990) Five decades of rice research. Kerala Agricultural University Press, Thrissur, India.

- Joseph KJ, Narayanan Nair ER, Bhaskaran S, Krishnakumari Amma PR (1990) The extent of adoption and constraints in the adoption of improved techniques by rice farmers in Alappuzha District, Kerala. In: Nair RR & K Balakrishna Pillai (Eds.), Rice in wetland ecosystem. Kerala Agricultural University Press, Thrissur, India.

- Tharamangalam J (1981) Agrarian class conflict, the political mobilization of labourers in Kuttanad, South India. University of Columbia Press, Vancouver, Canada.

- Maniyosai R, Kuruvilla A (2015) The changing land use pattern of Alappuzha district in Kerala, International Journal of Humanities and Social studies 3(6): 10-13.

- Harikumar A (2005) High rates of poverty prevailing in villages of Alappuzha district, The Hindu.

- The Hindu (2015) Kuttanad, the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS). The Hindu Daily.

© 2018 JG Ray. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)