- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Applications in Pharmacy & Pharmacology

Patient Education: Effective Vision for True Compliance

Mohiuddin Ak1*

1Department of Pharmacy, India

*Corresponding author: Mohiuddin AK, Faculty of Pharmacy, India

Submission: December 06, 2018;Published: January 03, 2019

ISSN 2637-7756Volume2 Issue3

Abstract

Patient education ensures that healthcare team is working together on patients’ individual medication plan, in conjunction with the rest of treatment, is vital to your recovery. Medication management is part of every patient’s plan of care. On an initial visit a clinician completes a comprehensive medication reconciliation. However, education is provided to every patient based on each medication the patient is prescribed. This includes its purpose, how and when to take it and how much of the medication to take. Medication reconciliation ensures that every possible side effect and interaction will be taken care that patients’ medications could possibly cause. Patients and caregivers are instructed symptoms that need to be reported to the physician based on the medication side effects and possible interactions with other medications/food.

Keywords: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP); Medical and non-medical context of education; National Council on Patient Information and Education (NCPIE); Patient compliance; Patient counselling; Patient Package Inserts (PPIs)

Background

The human and economic consequences of inappropriate medication use have been the subject of professional, public, and congressional discourse for more than two decades. Lack of sufficient knowledge about their health problems and medications is one cause of patients’ nonadherence to their pharmacotherapeutic regimens and monitoring plans; without adequate knowledge, patients cannot be effective partners in managing their own care.

Purpose of the study

Education may be provided by any healthcare professional who has undertaken appropriate training education, education on patient communication and education is usually included in the healthcare professional’s training. Health education is also a tool used by managed care plans and may include both general preventive education or health promotion and disease or condition specific education. Important elements of patient education are skill building and responsibility: patients need to know when, how, and why they need to make a lifestyle change. Group effort is equally important: each member of the patient’s health care team needs to be involved.

Scope of the study

There are many areas where patient education can improve the outcomes of treatment. For example, in patients with amputations, patient education has been shown to be effective when approached from all angles by the healthcare team (nurse, primary care physician, prosthetist, physical therapist, occupational therapist etc.). Preoperative patient education helped patients with their decision- making process by informing them of factors related to pain, limb loss, and functional restriction faced after amputation. In arthritic patients, education was found to be administered through three methods, including individual face to face meetings with healthcare professionals, patient groups, online support programs. Both age related and rheumatoid arthritis, patient education has been shown as an effective non-pharmacological treatment.

Methodology

About the article’s concern, the basic principles of drug education are presented with the underlying premise that these principles and strategies are applicable to any type of drug use. Although information about, and inherent problems resulting from, specific types of drug taking might vary from drug to drug or among reasons for use, the fundamental approach to educating people and fostering changes in drug use are the same. Various patient education programs are followed, mainly covering areas of rational prescribing, counselling, compliance and vigilance. The realization of patient education necessity demanded literature search from the arena of patient dealings. Journals, newsletters, magazine and program briefings on patient education thoroughly observed and reviewed.

Findings

Most societies are in great need of learning more rational and appropriate uses of all types of drugs and of gaining control over the drug products of their own technology. Humans have learned how to extract and synthesize drug products, yet humans have not learned fully how to use these products in an optimal manner. The primary importance of drug education is its benefit to the drug user (patient/ consumer); such education can improve the appropriateness of drug taking behaviours to achieve optimal health and well-being. At the centre of any educational effort is the provision of drug information, the strategy with which pharmacists and pharmacy students are most familiar. In today’s highly complex, technological world, the availability of current and precise information allows one to understand, to make better choices, and to prevent or solve problems.

Limitations of the study

Many approaches have been developed for designing drug information and drug education programs in medical settings, and many of these are described in various articles mostly on drug abuse. The majority of the examples in this article, therefore, exclude realm of drug abuse prevention. These techniques and strategies, and their basic principles, are also applicable to educating patients about medicines or providing drug education programs in any context. It is important to realize that, conversely, ideas, strategies, and programs from the field of patient drug education can be relevant to the development of programs on the nonmedical use of drugs, and some examples of this broader view of drug education are provided.

Practical implication of the study

Most pharmacists are aware of the important problems that potentially can occur with the appropriate use of prescription medications, such as adverse reactions and drug interactions. Many pharmacists also are knowledgeable about potential problems inherent in self-medication with a non-prescription drug, though they probably are less familiar with the use of herbal remedies and homeopathic medications in the same context. Few pharmacists, however, are aware of potential problems that can arise with social-recreational drug use. Regardless of the situation, the problem of poisoning or overdose by a drug should be delegated to poison-control centres and hospital emergency rooms. The individual pharmacist, particularly one working in a community setting, may not feel capable of consulting or educating a particular drug consumer in these problem areas.

Social impact of the study

Drug use occurs in virtually every society and culture. Whether the use of a particular drug is for a medical or a nonmedical reason, problems resulting from use often arise. Preventing drug use problems is a major concern of most societies, and it usually is highlighted when specific outbreaks problems or inappropriate use occur. As pharmacy is the profession to which the control of drugs is attributed, it should be involved intimately with those activities aimed at preventing or reducing drug use problems. In fact, the pharmaceutical profession should be providing the leadership and directing the research in this area. It is unfortunate that, on the whole, pharmacy has been lacking in its social responsibility for the chemical substances it develops, promotes, and dispenses.

Introduction

The pharmacy profession has accepted responsibility for providing patient education and counselling in the context of pharmaceutical care to improve patient adherence and reduce medication- related problems. Providing pharmaceutical care entails accepting responsibility for patients’ pharmacotherapeutic outcomes. Pharmacists can contribute to positive outcomes by educating and counselling patients to prepare and motivate them to follow their pharmacotherapeutic regimens and monitoring plans. The purpose of this document is to help pharmacists provide effective patient education and counselling. In working with individual patients, patient groups, families, and caregivers, pharmacists should approach education and counselling as interrelated activities. ASHP believes pharmacists should educate and counsel all patients to the extent possible, going beyond the minimum requirements of laws and regulations; simply offering to counsel is inconsistent with pharmacists’ responsibilities. In pharmaceutical care, pharmacists should encourage patients to seek education and counselling and should eliminate barriers to providing it.

Expected area of coverage for education

According to ASHP patient education and counselling guidelines are applicable in all practice settings including acute inpatient care, ambulatory care, home care, and long-term care-whether these settings are associated with integrated health systems or managed care organizations or are freestanding. The guidelines may need to be adapted; for example, for use in telephone counselling or for counselling family members or caregivers instead of patients. Patient education and counselling usually occur at the time prescriptions are dispensed but may also be provided as a separate service [1]. The techniques and the content should be adjusted to meet the specific needs of the patient and to comply with the policies and procedures of the practice setting. In health systems, other health care team members share in the responsibility to educate and counsel patients as specified in the patients’ care plans. In addition to a current knowledge of pharmacotherapy, pharmacists need to have the knowledge and skills to provide effective and accurate patient education and counselling. They should know about their patients’ cultures, especially health and illness beliefs, attitudes, and practices. They should be aware of patients’ feelings toward the health system and views of their own roles and responsibilities for decision-making and for managing their care. Effective, open-ended questioning and active listening are essential skills for obtaining information from and sharing information with patients. Pharmacists have to adapt messages to fit patients’ language skills and primary languages, through the use of teaching aids, interpreters, or cultural guides if necessary. Pharmacists also need to observe and interpret the nonverbal messages (e.g., eye contact, facial expressions, body movements, vocal characteristics) patients give during education and counselling sessions [2].

Assessing a patient’s cognitive abilities, learning style, and sensory and physical status enables the pharmacist to adapt information and educational methods to meet the patient’s needs. A patient may learn best by hearing spoken instructions; by seeing a diagram, picture, or model; or by directly handling medications and administration devices. A patient may lack the visual acuity to read labels on prescription containers, markings on syringes, or written handout material. A patient may be unable to hear oral instructions or may lack enough motor skills to open a child-resistant container [3]. In addition to assessing whether patients know how to use their medications, pharmacists should attempt to understand patients’ attitudes and potential behaviours concerning medication use. The pharmacist needs to determine whether a patient is willing to use a medication and whether he or she intends to do so [4].

Pharmacists requirements

The individual best suited to assist people in preventing drug use problems and in achieving optimal, desired experiences from their drug taking is the pharmacist. The pharmacist is an accessible source of high-quality information and educational programs and should be concerned with a person’s drugtaking behaviour [5]. Whether it be the use of a prescription medicine or an herbal remedy to achieve or maintain a state of health, the use of a drug for its socially oriented effects in a recreational setting, or the ingestion of a chemical substance to enhance a religious or aesthetic experience, the perspective presented herein considers the pharmacist to be the leader in efforts to prevent or limit drug use problems. Pharmacy professionals of assigned or specified area seek opportunities to participate in health-system patient-education programs and to support the educational efforts of other health care team members. Pharmacists should collaborate with other health care team members, as appropriate, to determine what specific information and counselling are required in each patient care situation. A coordinated effort among health care team members will enhance patients’ adherence to pharmacotherapeutic regimens, monitoring of drug effects, and feedback to the health system [6,7].

Required environment

Education and counselling should take place in an environment conducive to patient involvement, learning, and acceptance-one that supports pharmacists’ efforts to establish caring relationships with patients. Individual patients, groups, families, or caregivers should perceive the counselling environment as comfortable, confidential, and safe [8]. Education and counselling are most effective when conducted in a room or space that ensures privacy and opportunity to engage in confidential communication. If such an isolated space is not available, a common area can be restructured to maximize visual and auditory privacy from other patients or staff. Patients, including those who are disabled, should have easy access and seating. Space and seating should be adequate for family members or caregivers. The design and placement of desks and counters should minimize barriers to communication. Distractions and interruptions should be few, so that patients and pharmacists can have each other’s undivided attention. The environment should be equipped with appropriate learning aids, e.g., graphics, anatomical models, medication administration devices, memory aids, written material, and audio-visual resources [9].

Pharmacist and patient roles

Pharmacists and patients bring to education and counselling sessions their own perceptions of their roles and responsibilities. For the experience to be effective, the pharmacist and patient need to come to a common understanding about their respective roles and responsibilities. It may be necessary to clarify for patients that pharmacists have an appropriate and important role in providing education and counselling [10]. Patients should be encouraged to be active participants. The pharmacist’s role is to verify that patients have sufficient understanding, knowledge, and skill to follow their pharmacotherapeutic regimens and monitoring plans. Pharmacists should also seek ways to motivate patients to learn about their treatment and to be active partners in their care [11]. Patients’ role is to adhere to their pharmacotherapeutic regimens, monitor for drug effects, and report their experiences to pharmacists or other members of their health care teams. Optimally, the patient’s role should include seeking information and presenting concerns that may make adherence difficult. Depending on the health system’s policies and procedures, its use of protocols or clinical care plans, and its credentialing of providers, pharmacists may also have disease management roles and responsibilities for specified categories of patients. This expands pharmacists’ relationships with patients and the content of education and counselling sessions [12].

Drug use and drug education

Human beings engage in a great variety of drug taking behaviours, but one of the most important and rudimentary considerations involves the definition of what constitutes a drug and which situations characterize drug taking. Reports indicate that self-diagnosis, occurs in the majority of illness episodes and that self-medication occurs from 60% to 90% of the time in these situations. The prevalence of non-prescription drug use is even higher in the older adult population (ranging from 50% to 90%), in addition to their extensive use of prescription drugs. Antibiotics are commonly self-medicated drugs worldwide, with over 50% purchased and used without a prescription [13]. When a drug is prescribed for a patient, health professionals expect that the drug will be taken precisely as directed. Compliance with medication regimens is another type of drug taking considered of major importance in a successful treatment plan. There have been many studies in this area; their results have shown that anywhere in general, probably ranges from 33% to 50% in any given population. This situation represents a different behaviour; many patients are not taking drugs when they should be.

Basic principles of drug education

Various strategies and techniques exist for use in counselling and educating patients, but before these are considered, the pro cess through which learning takes place is reviewed. The process of learning occurs in three domains or in three different ways [14]. The basic domain is cognitive, where facts and information are assimilated. A person’s knowledge is built through a process of acquiring, understanding, retaining (memory), and reinforcing specific bits of information. The next domain (affective) involves the formation of attitudes such as feelings, beliefs, perceptions, emotions, and appreciations. Things patients need to follow are:

A. Intensity-how much (single dose)

B. Frequency- how often (dosing schedule)

C. Duration-how long (length of use)

These are constructed through an interactive process, combining knowledge (from the cognitive domain) and real-life experiences during which the person’s knowledge is applied and evaluated to see if it fits that of reality. The behavioural domain (eg, actions, decision- making, physical abilities) is developed from what the person knows and feels, in conjunction with the nature and requirements of their social environment.

Drug education in a medical context

Drug taking in a medical context often is influenced or directed by a health professional. The drug educator should not forget this audience in planning and developing drug education programs. The primary group is the drug prescriber, mostly physicians. Research has shown that prescribing behaviours are influenced by numerous factors, including prescriber education and training; drug advertising and promotion; interactions with colleagues; control and regulatory mechanisms in health care; and the demands of patients and society. Drug information newsletters and other services, counter detailing and screening pharmaceutical representatives, in-service seminars and presentations and drug utilization review with feedback and consultation are the most commonly used approaches to improve drug knowledge and change prescribing practices. At one end of the spectrum, a drug information sheet (also called a study instruction sheet), education card, or PPI is given to the patient along with the medication. Information sheets in languages other than English, and in a pictorial format for those who cannot read, also have been designed. Programmed instruction sheets, which provide both information and auto-tutorial learning with reinforcement, also have been developed and used in pharmacy. The value and effectiveness of sheets is variable, with the greatest degree of learning occurring in the cognitive domain. Another strategy involves the use of behaviour modification to assure appropriate drug use. This problem-solving process employs the observation of behaviour, cueing (some type of motivator or reminder to initiate behaviour), and rewards to define and modify behaviour in a specific way. The patient learns about the medical condition and drug regimen, and then implements a self-management program related to his particular therapy. The patient becomes a partner in the planning of therapy, and consequently feels responsible for following the agreed-upon regimen. These two techniques, social support and behaviour modification programs, have been found to be effective in improving patient compliance with medication regimens [15].

Potential directions for patients

A. Pharmacists and physicians provide their patients with written directions outlining the proper use of the medication prescribed. Frequently, these directions include the best time to take the medication, the importance of adhering to the prescribed dosage schedule, what to do if a dose is missed, the permitted use of the medication with respect to food, drink, and/or other medications the patient may taking, as well as information about the drug itself.

B. Certain manufacturers have prepared patient package inserts (PPIs) for specific products for issuance to patients. These present to the patient information regarding the usefulness of the medication as well as its side effects and potential hazards.

C. The information is also available on computer software, allowing leaflets to be printed in the pharmacy as needed and with a compatible computer and standard line printer. Similar computer software programs are available from various other sources, designed to generate personalized patient-counselling information for use by the pharmacist in patient education.

Many studies on patient package inserts (PPIs), for instance, have found that this form of printed information can lead to reliable gains in drug knowledge, but they seem to have little effect on how patients use a drug. Although the patients’ knowledge and understanding (cognitive domain) of the drug and drug regimen were improved, their initial decisions regarding drug therapy, their intention of using the drug (attitudinal domain), and their actual compliance with the regimen were not changed greatly. The same also holds in educating people about nonmedical drug use. The relation between what a person knows about the nonmedical use of drugs and whether a person actually uses drugs in such a way is not very strong, according to most of the research in this area [16]. This body of research also suggests that the relation between knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour is unclear and may be weak or inconsistent for some individuals or in some drug taking situations.

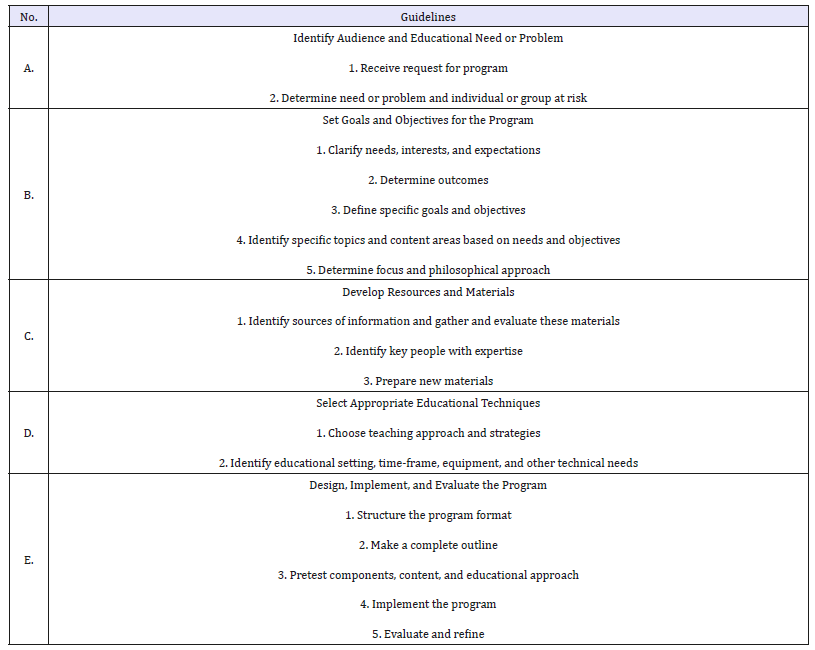

Developing drug-education programs

In using any particular educational strategy or program, the pharmacist should be familiar with its goals and content, the target audience for whom it is intended, its biases and flaws, the results of any evaluation studies performed on it, it’s known effect on actual use and practical considerations such as costs, time and manpower requirements, materials and equipment, and extra training (Table 1).

The Competencies of a health educator include the following:

A. Incorporate a personal ethic in regard to social responsibilities and services towards others.

B. Provide accurate, competent, and evidence-based care.

C. Practice preventative health care.

D. Focus on relationship-cantered care with individuals and their families.

E. Incorporate the multiple determinants of health when providing care.

F. Be culturally sensitive and be open to a diverse society.

G. Use technology appropriately and effectively.

H. Be current in the field and continue to advance education.

Table 1:Guidelines for developing a drug education program.

Extended roles of a pharmacist

The pharmacist also should consider the promotion of educational programs and services, so that the patients and consumers become aware of and use them. The promotion of such services is similar, in concept, to the promotion of any product or service. Detailed descriptions may be found in any reference book on marketing, advertising, or business practices. There are many specific techniques that can be used in promotion. Some are free of cost and involve only a small amount of time, whereas the willingness to spend more time and money leads to more intricate and diverse promotional schemes. One comprehensive way is through the local mass media. It is not difficult to contact the local town or neighbourhood newspaper, local TV or radio station, and local cable networks and ask for a news story or even request an interview that would describe the new educational services that will be provided to the community The Dynamic of Pharmaceutical Care [17].

The value of patient education

A. Improved understanding of medical condition, diagnosis, disease, or disability.

B. Improved understanding of methods and means to manage multiple aspects of medical condition.

C. Improved self-advocacy in deciding to act both independently from medical providers and in interdependence with them.

D. Increased Compliance Effective communication and patient education increases patient motivation to comply.

E. Patient Outcomes Patients more likely to respond well to their treatment plan fewer complications.

F. Informed Consent-Patients feel you’ve provided the information they need.

G. Utilization-More effective use of medical services-fewer unnecessary phone calls and visits.

H. Satisfaction and referrals-Patients more likely to stay with your practice and refer other patients.

I. Risk Management-Lower risk of malpractice when patients have realistic expectations

Improving compliance through patient education

Pharmacists have a particularly valuable opportunity to encourage compliance since their advice accompanies the actual dispensing of the medication, and they usually are the last health professional to see the patient prior to the time the medication is to be used.

Development of treatment plan: The more complex the treatment regimen, the greater is the risk of noncompliance, and this must be recognized in the development of the treatment plan. The use of longer-acting drugs in a therapeutic class, or dosage forms that are administered less frequently, also may simplify the regimen. The treatment plan should be individualized because of the patient’s needs, and when possible, the patient should be a participant in decisions regarding the therapeutic regimen.

Education priorities: One of the findings of the report of the Office of the Inspector General is “education is the best way to improve compliance.” Complex terms and unnecessary jargon are never appreciated by any patient. Patient should repeat the instructions for their better understanding and memorization and also should be encouraged to ask questions.

Oral communication/counselling: Oral communication is the most effective patient education tool. Its most effective when privacy assured and free of distraction.

Written communication: Many pharmacists provide patients with medication instruction PPIs. Information that pertains to the specific medication/formulation being dispensed is preferred to information that applies to a therapeutic class of agents or a general statement that applies to all dosage forms of a particular medication. The provision of supplementary PPIs appears to be most effective in improving compliance with short-term therapeutic regimens (e.g., antibiotic therapy). For drugs used on a long-term basis, written information as plays an important role for patient compliance.

Audio-visual materials: The use of audio-visual aids may be particularly valuable in certain situations because patients may get a better picture of the illness or how their medication acts or is to be administered (e.g., the administration of insulin, the use of a metered-dose inhaler). An increasing number of health-care professionals have used such aids effectively by making them available for viewing in a patient waiting area or consultation room and then answering questions the patient may have.

Patient motivation: Information must be provided to patients in a manner that is not coercive, threatening, or demeaning. The best intentioned, most comprehensive educational efforts will not be effective if the patient cannot be motivated to comply with the instructions for taking the medication. The physician-patient interaction has been characterized as a negotiation. This concept may be extended further by the development of contracts between patients and health-care providers in which the agreed-upon treatment goals and responsibilities are outlined [18].

Advancing compliance: NCPIE panels make recommendations

In National Council on Patient Information and Education (NCPIE) sponsored a conference, “Advancing Prescription Medicine Compliance: New Paradigms, New Practices.” The most important objective of this conference was to produce realistic recommendations for advancing compliance across health care professions and practice settings (Advancing Prescription, 1st Edition). To develop recommendations, commissioned speakers addressed prescription medicine compliance issues [19] relating to physicians, pharmacists, nurses, manufacturers, patients, managed care organizations, NCPIE and other groups. Each speaker suggested what could be done to improve compliance. Six complementary working groups then used the speakers’ ideas as a springboard in developing recommendations for each group and for groups in collaboration. These were then presented to the full conference for participants’ response and consideration. The following recommendations are directed to the varied organizations and individuals who can advance compliance; however, many recommendations apply to more than one category under which they are listed:

Physicians and medical schools

A. Involve the patient in treatment decisions.

B. Monitor compliance with prescribed treatment at every patient visit; follow up outside of scheduled visits as appropriate. Give the patient an alternate contact person at your office if you might be unavailable when he/she calls between visits.

C. Document patient compliance using a compliance-monitoring form that can be incorporated into the patient’s record.

D. Coordinate patients’ medication regimens with health professionals providing remote site care, including visiting nurses, physician assistants and nurses in satellite clinics or offices, and pharmacists working with patients in care facilities or in the phar macy.

E. Include patient communication skills in medical training and continuing education curricula.

F. Train physicians to communicate with other members of the health care team to ensure continuity of care.

Pharmacists, pharmacy-providers and educators

A. Become proactive about gathering and providing medicine information. Ask questions that stimulate dialogue, discuss care plans with patients, and use information about patients to make better decisions.

B. Provide compliance monitoring and documentation for at least one at-risk patient per month. Share your findings with the patient and with his/her other health care providers.

C. Work with management to redesign facilities to increase pharmacist/patient contact, and to provide a private counselling area.

D. Incorporate patient communication skills and new teaching methods into undergraduate courses and continuing education programs.

E. Work with other health professional schools/organizations to develop interdisciplinary compliance education programs.

F. Integrate behavioural and clinical sciences in educating pharmacists about compliance.

Individual nurses and educators

A. Integrate into each patient encounter an educational assessment of patient medicine knowledge.

B. Collaborate with other health care providers, including prescribers and pharmacists, about patient compliance issues.

C. Develop programs to increase nurses’ knowledge and skills for compliance-enhancement.

D. Include compliance questions in examinations for professional degrees, licensing, and continuing education.

All Health professionals

A. Individualize patient care, including medication management, considering factors such as age, culture, gender, attitudes, and personal situation.

B. Specifically ask patients about use of over-the-counter drugs, including vitamins and dietary supplements.

C. Engage in a dialogue with patients and involve them as partners in the treatment process. Explain why you think a treatment plan is most appropriate for your patient.

D. Use written materials to reinforce oral counseling, not as a substitute for it.

E. Respect a patient’s right to confidentiality when sharing medication compliance experience with the patient’s other health care providers, including nurses, pharmacists, physicians, and physician assistants.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers

A. Individually and as an industry, develop a public service advertising campaign promoting patient medication compliance with therapy.

B. Support health professionals’ education to develop effective communicators in a patient-centered health care system.

C. Recognize and promote role models who can demonstrate improved compliance from a patient-cantered approach.

D. Support interdisciplinary teams that provide patient education and programs for compliance and health promotion.

Patients

A. Become an active participant in making treatment decisions and solving problems that could inhibit proper medicine use.

B. Talk to your health professionals about why and how to use your prescription medicines. Give them information about your medicine use

C. (prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins and dietary supplements) and health. If you stop or change a prescribed treatment, tell them and explain why you did this. Get the answers to any questions you have.

D. Recognize, accept, and carry out your responsibilities in the treatment regimen.

Managed care organizations and hospitals

A. Use existing databases to profile the extent of medicine noncompliance among your health plan members.

B. Develop and implement programs for patient compliance support (e.g., group support programs, educational interventions, monitoring clinics,

C. compliance packaging aids, and brown bag reviews). Keep health care providers informed about these programs so they can refer appropriate

D. patients as part of an individualized compliance regimen.

E. Develop and implement innovative programs that teach patient’s responsibility for and involvement in his/her health care.

F. Identify, implement, and evaluate compliance-promoting organizational practices and policies.

G. Review drug use policies, such as formulary policy guidelines, from a patient compliance perspective. Revise policies accordingly to facilitate

H. compliance.

I. Develop and implement computerized systems that allow departments to share clinical patient information electronically.

Further recommendations

Leadership: While the rest of the world has made great advancements to enhance the consumer experience, healthcare organizations have been slower to change their ways, making patients conform to the needs of the system. Evolution requires a change in culture, philosophy, and technology. Greater visibility into processes is ensuring control, quality and safety measures within hospitals, clinics, model pharmacies and any healthcare settings.

Medical records management: Leveraging the improvements in technology to link databases and systems with automated forms yields timelier reporting and tracking of patient records of history, medication and provider’s instruction. Continue monitoring is the soul of compliance and control. From artificial intelligence to machine learning, health systems should be exploring all kinds of innovations to move healthcare forward.

Staff training and professional credentialing: The ability for the human resources department to have greater reporting capabilities to determine license validity and visibility into license expiration. Non-compliance can be improved by simply reminding patients to take their medication. More information means a more compliant patient. As with the reminder services, the concept of providing information to improve compliance has been a highly appealing solution. Although understanding the condition and treatment is important, provision of information alone does not often provide the solution. There have been studies in chronic conditions such as asthma, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes that have seen drastically improvement of compliance.

Quality monitoring: Henry Ford says, “Quality is doing right when no one is looking”. Clinicians have limitation in giving time to patients, which make patients more often non-compliant. Hospital pharmacists can, through counseling, listening and building relationships can impact not only satisfaction scores, but also compliance and outcomes.

Patient satisfaction observation: Patients who are least solvent, at least a once think to take treatment from abroad as most of them lost faith in public and private hospitals, low utilization of public health facilities, and increasing outflow of patients to hospitals in neighboring countries. A counseling service standard, proper monitoring during prescribing, compounding and dispensing can impart little effort to involve them in measuring satisfaction or defining health service standards. Both pharmacists and doctors can play strong role in influencing patient satisfaction in hospitals.

Easy to understand and short PPIs: Single-page consumer- oriented drug information sheets may be produced for distribution. Assistance for the printing of such materials may be obtained from local agencies and businesses as a show of community support. There is also the accepted practice of promoting a new service by informing lay people or community groups about them. Through a process of diffusion, this information is shared with a larger number of people who come in contact with those who have been informed. In most communities, key people or groups include teachers and counsellors at local schools, Rotary clubs, women’s clubs, consumer groups, governmental agencies, social and welfare organizations, chemical-dependency agencies, and other health professionals in the area.

Conclusion

With constant change to the physical, biological, cultural, social, and economic environment, both pharmacists and citizens should cultivate an informed awareness of these changes, and health providers should adapt their methods of health education, disease prevention, and disease control to the changes in each community. In practical terms, the success of future programs and activities depends on a clearer and more coordinated effort in using the strategies and techniques that have been developed and tested. Health professionals, the family, schools, and communities should combine their efforts and integrate drug- education strategies into ongoing activities, instead of just adding them onto irrelevant courses and programs. Attitudinal strategies and basic drug information should be combined in educational programs. The various structured and pre-packaged materials and techniques should be selected and synthesized into programmatic formats that best meet the needs of the target audience. It is important to identify individuals or groups at high risk for developing drug-use problems and to focus educational and prevention efforts on their needs. Finally, a humanistic approach, in which drug taking is considered a natural kind of behaviour and in which an awareness of different values is stressed, should be brought into educational programming. Regardless of the degree of involvement, it is time for pharmacists and the pharmaceutical profession to provide more drug education programs for their patients and all of society.

Acknowledgement

It’s a great gratitude and honor to be a part of healthcare research and education. Providers of all disciplines that I have conducted was very much helpful in discussing patient counseling, prescribing frameworks, patient compliance through effective education- care and monitoring by providing books, journals, newsletters and precious time. The greatest help was from my students who paid interest in my topic as class lecture and encouraged to write such article comprising patient education and compliance. Despite a great scarcity of funding this purpose from any authority, the experience was good enough to carry on research.

References

- The American Pharmacists Association (2017) Practice guidance for pharmacy-based medication administration services.

- Randy PM, Marialice S Bennett (2006) Improving communication skills of pharmacy students through effective precepting. Am J Pharm Educ 70(3): 58.

- Mounica B, Nallani VR, Sharmila N, Ramarao N (2014) A Clinical pharmacist role in patient counselling in health care services in India - an over view. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice & Drug Research 4(3): 124-131.

- Cara M (2014) Strategies for improving the quality of verbal patient and family education: a review of the literature and creation of the EDUCATE model. Health Psychol Behav Med 2(1): 482-495.

- APHA (American Public Health Association) (2006) The role of the pharmacist in public health policy.

- (2018) PSSNY the pharmacy patient’s right to care transforming access to healthcare for the pharmacy patient in NEW YORK state the pharmacists society of the state of New York Legislative Agenda.

- Paul RT (2001) The health care team members: who are they and what do they do? Jones and Bartlett publishers, LLC. committee on quality of health care in America, institute of medicine, national academy of sciences. crossing the quality Chasm. In: A New health system for the 21st century Washington: National Academy Press, USA.

- Huda K, Ramsha R, Safila N (2014) Evaluation of patient counselling in different hospital of Karachi, Pakistan; a neglected domain of pharmacy. International Research Journal of Pharmacy 5(3).

- (2007) Clinical practice guidelines guidelines of the American society of consultant pharmacists. Assisted Living Consult.

- Alkhawajah AM, Eferakeya AE (1992) The role of pharmacists in patient’s education on medication. Public Health 106(3): 231-237.

- Jolly F, Suja A (2014) Clinical pharmacists: Bridging the gap between patients and physicians. Saudi Pharm J 22(6): 600-602.

- WHO (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies evidence for action who library cataloguing-in-publication data. World Health Organization.

- Dnyanesh L, Vaidehi L, Gerhard F, Gerard K (2018) Self-medication practices in urban and rural areas of western India: a cross sectional study. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health 5(7): 2672-2685.

- Sarah MS (2018) Domains of learning retrieved from explorable.

- WHO (2012) Promoting rational prescribing chapter 29? Management Sciences for Health.

- Robert HVT (2004) Impact of written drug information in patient package inserts: Acceptance and impact on benefit/risk perception.

- MERK, APhA (2007) The dynamics of pharmaceutical care: Enriching patients using relationship marketing to expand pharmacy services. Health A Continuing education series supported by an educational grant. The American Pharmacists Association.

- Manmohan T, Sreenivas G, Sastry VV, Sudha ER, Indira K, et al. (2012) Drug compliance and adherence to treatment. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 1(3): 142-159.

- Advancing Prescription Medicine Compliance (21st edn), In: Jack E Fincham (Ed.), New Paradigms, New Practices Journal of Pharmacoepidemiology.

© 2019 Mohiuddin Ak. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)