- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Applications in Pharmacy & Pharmacology

A Brief Review of Patient Rights in Pharmacy Profession

Mohiuddin Ak1*

Faculty of Pharmacy, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author: Mohiuddin Ak, Faculty of Pharmacy, Bangladesh

Submission: December 06, 2018;Published: January 03, 2019

ISSN 2637-7756Volume2 Issue3

Abstract

Pharmacy is regarded as one of the most trusted professions in the world. Doctors are very important part of our society. They diagnose the disease and prescribe the medicines for the treatment of the diseases. Like Doctors, Pharmacist is also very important personality because he formulates the medicines, which are prescribed by doctors. So, we can say that without pharmacist, doctors cannot improve the public health and cannot cure the disease. Now, in 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognizes “the inherent dignity” and the “equal and unalienable rights of all members of the human family”. And it is on the basis of this concept of the person, and the fundamental dignity and equality of all human beings, that the notion of patient rights was developed. In other words, what is owed to the patient as a human being, by physicians and by the state, took shape in large part thanks to this understanding of the basic rights of the person.

Purpose of the study: Discussion and projection about pharmacy profession and its characteristics, professional behavior and ethical aspects. The pharmacists have a vital role to play with patient rights.

Findings: As a human being, patient have several rights to be followed during treatment intervention. Pharmacists are yet to get their status as a healthcare provider to follow and honor those rights.

Materials and Methods: Research conducted a comprehensive year-round literature search, which included books, technical newsletters, newspapers, journals, and many other sources. Medicine and technical experts, pharma company executives and representatives were interviewed. Projections were based on all ethical and professional aspects pharmacists need to cover, including patient rights.

Research limitations: Very few areas in Asian countries, the patient rights are recognized or followed. Very few providers like to talk about patient rights because of their commercialism and busy schedule. Pharmacists as healthcare professionals are yet to be explored in this arena. Patient literacy and understanding is also a factor why these rights are merely discussed and followed.

Practical Implication: The soul of this article was to detail pharmacy profession and ethics towards patient rights, in simple words. Along with students, researchers and professionals of different background and disciplines, eg. Pharmacists, marketers, doctors, nurses, hospital authorities, public representatives, policy makers and regulatory authorities have to acquire much from this article.

Social Implication: Pharmacists have several scopes to work in healthcare system in a country like Bangladesh as there is a scarcity of resources, fewer access to general people for adequate and better treatment. The article should contribute an integrated discussion about the importance of pharmacy professionals at different levels of healthcare settings in detailing the patient rights.

Keywords: Ethics; Consumerism Vs paternalism; Partnership; Patientr; Provider patient Relationship; Healthcare policy

Introduction

There is a lack of interaction between pharmacist and patient in our society, which worsens the public health because when pharmacist does not know about the problems of the patient, he will not be able to formulate those medicines, which can cure the patient, and which are effective against patient’s disease. We need to enhance the interaction between pharmacist and patient. From conversation with a patient, a pharmacist must be able to identify and evaluate important health aspects which may need attention. Government restricts the practice of Pharmacy to those who qualify under regulatory requirements and grant them privileges necessarily denied to others. In return Government expects the Pharmacist to recognize his responsibilities and to fulfill his professional obligations honorably and with due regard for the well-being of society. Standards of professional conduct for pharmacy are necessary in the public interest to ensure an efficient pharmaceutical service.

An understanding of patient rights and practice is a completion approach in pharmacists’ healthcare service. Also, the code of ethics [1] covers the area of patient rights. “A pharmacist respects the autonomy and dignity of each patient…A pharmacist respects the values and abilities of colleagues and other health professionals…. A pharmacist seeks justice in the distribution of health resources”

Patient rights determination in professional characteristics

Health professional-patient relationship: consumerism vs paternalism: It was not long ago that when a patient was instructed by their physician or pharmacist to take a medication, they did so without question. Medical paternalism-the belief that the health care professional knew best-was accepted as standard practice by most health care professionals and their patients.

Relationship with the patient: Pharmacists are primarily visible in the healthcare chain. Pharmacists are employed throughout the pharmaceutical chain, from design and production to the dispensing of a medicine and counselling. Regardless of where each pharmacist works, however, his professional actions take place in a context in which:

A. The patient is at the center of the practice;

B. A confidential relationship between pharmacist and patient is essential;

C. Decisions are taken bearing in mind the patient’s expectations and experiences;

D. Success is determined by the outcome achieved for the patient;

E. The patient’s needs determine the place of practice

F. Each patient receives access to the medicine in the same way and to the same extent;

G. Patient care is supported by the product, the documentation and the administration (Charter Professionalism of the pharmacists).

Partnership: A good partnership between a practitioner and the person they are caring for requires high standards of personal conduct. This involves:

A. Being courteous, respectful, compassionate and honest

B. Treating each patient or client as an individual

C. Protecting the privacy and right to confidentiality of patients or clients, unless release of information is required by law or by public interest considerations

D. Encouraging and supporting patients or clients and, when relevant, their career/s or family in caring for themselves and managing their health

E. Encouraging and supporting patients or clients to be well-informed about their health and assisting patients or clients to make informed decisions about their healthcare activities and treatments by providing information and advice to the best of a practitioner’s ability and according to the stated needs of patients or clients

F. Respecting the right of the patient or client to choose whether or not they participate in any treatment or accept advice, and Recognizing that there is a power imbalance in the practitioner-patient/client relationship and not exploiting patients or clients physically, emotionally, sexually or financially (Code of conduct for registered health practitioners)

Patient’s rights

Patients generally choose their own physician, pharmacy, and hospital. Patients are allowed to choose from multiple options of treatment when they exist. Patients must give their approval, through the process of informed consent, prior to the initiation of care. All the preceding presupposes that treatment is available and that the patient has the economic wherewithal to pay for that treatment. For patients who are uninsured or lack the ability to pay, the right to choose the nature of their health care is meaningless. Patients also have a right to treatment that is both safe and effective within given parameters.

Ethical principles and moral rules

The code of conduct to guide decision making for pharmacist and maintain ethical integrity varies according to the country and professional body that creates the guidelines. However, the ethical principles are similar and can be separated into five main categories: the responsibility for the consumer, the community, the profession, the business and the wider healthcare team. The ethical responsibilities of a pharmacist that relate to the consumer include:

A. To recognize the consumer’s health and wellbeing as their first priority and utilize knowledge and provide compassionate care in an appropriate and professional manner.

B. To respect the consumer’s autonomy and rights and assist them in making informed decisions about their health. This should include respecting the dignity, privacy, confidentiality, individuality and choice of the consumer.

Ethical principles and moral rules provide guidance for practitioners about what the commitments of patient care entail:

Autonomy

The principle of autonomy states that an individual’s liberty of choice, action, and thought is not to be interfered with. In health care, we think of autonomy as the right of individuals to make decisions about what will happen to their bodies, what choices will be made among competing options, and what they choose to take, or not take, into their bodies. We also allude to questions of autonomy when we refer to choose among health care providers, and the choice of refusing medical treatment. One controversy involves mature minors, argument is the cognitive development of those who are 15 to 17 years of age qualifies them to make their own medical decisions. Another area of controversy involves those in the early and middle stages of Alzheimer’s disease [2].

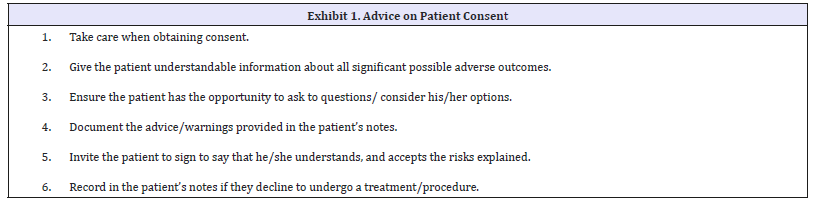

Informed consent

The principle of autonomy is a vital component of informed consent. The rule of informed consent directs that patients must be fully informed about the benefits and risks of their participation in a clinical trial, taking a medication, or electing to have surgery, and this disclosure must be followed by their autonomous consent. The phrase “informed consent” has become firmly established in the clinical field, and it seems that physicians spend more time than previously explaining to patients about their health condition [3]. Consent is invalid when it is given under pressure or coercion. Therefore, it is important that consent is obtained for each act and not assumed because this is a routine assessment or procedure and therefore can be carried out automatically. It is essential the patient understands their diagnosis, the benefit and rationale of the proposed treatment and the likelihood of its success together with the associated risks and consequences, for example side effects. Therefore, a prescriber needs to discuss these aspects with the patient. In addition, potential alternative treatments should also be discussed to allow the patient to make a comparison with the proposed plan. The prognosis if no treatment is prescribed should also be discussed. Such a wide-ranging discussion may require more than one appointment and reinforces the necessity for an ongoing patient-professional relationship focused on the needs of the patient. The information disclosed should include:

A. The condition/disorder/disease that the patient is having/suffering from

B. Necessity for further testing

C. Natural course of the condition and possible complications

D. Consequences of non-treatment

E. Treatment options available

F. Potential risks and benefits of treatment options

G. Duration and approximate cost of treatment

H. Expected outcome

I. Follow-up required [4].

Table 1:

(Table 1) It is important to communicate the risks and benefits of treatment in relation to medicines. This is because many medicines are used long term to treat or prevent chronic diseases, but we know they are often not taken as intended. Sometimes these medicines do not appear to have any appreciable beneficial effect on patients’ symptoms, for example medicines to treat hypertension. Most patients want to be involved in decisions about their treatment and would like to be able to understand the risks of side effects versus the likely benefits of treatment, before they commit to the inconvenience of taking regular medication. An informed patient is more likely to be concordant with treatment, reducing waste of health care resources including professional time and the waste of medicines which are dispensed but not taken [5].

Communicating risk is not simple. Many different dimensions and inherent uncertainties need to be considered, and patients’ assessment of risk is primarily determined by emotions, beliefs and values, not facts. This is important, because patients and health care professionals may ascribe different values to the same level of risk. Health care professionals need to be able to discuss risks and benefits with patients in a context that would enable the patient to have the best chance of understanding those risks. It is also prudent to inform the patient that virtually all treatments are associated with some harm and that there is almost always a trade-off between benefit and harm. How health care professionals present risk and benefit can affect the patient’s perception of risk [6].

Confidentiality

Medical confidentiality need not be requested explicitly by patients; all medical information, by nature, is generally considered to be confidential, unless the patient grants approval for its release. Confidentiality in medicine involves a careful balance of respecting patient autonomy, the duty to warn, protecting confidential patient information, and soliciting appropriate disclosures [7]. Confidentiality in relation to genetic information is likely to present a common ethical dilemma as it becomes possible to screen for gene mutations linked to an increasing number and type of diseases [8]. Confidentiality and privacy have received a great deal of attention recently with the passage and implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA) Act. Good practice involves:

A. Treating information about patients or clients as confidential and applying appropriate security to electronic and hard copy information.

B. Seeking consent from patients or clients before disclosing information, where practicable.

C. Being aware of the requirements of the privacy and/ or health records legislation that operates in relevant states and territories and applying these requirements to information held in all formats, including electronic information.

D. Sharing information appropriately about patients or clients for their healthcare while remaining consistent with privacy legislation and professional guidelines about confidentiality.

E. Where relevant, being aware that there are complex issues relating to genetic information and seeking appropriate advice about disclosure of such information.

F. Providing appropriate surroundings to enable private and confidential consultations and discussions to take place.

G. Ensuring that all staff are aware of the need to respect the confidentiality and privacy of patients or clients and refrain from discussing patients or clients in a non-professional context.

H. Complying with relevant legislation, policies and procedures relating to consent.

I. Using consent processes, including formal documentation if required, for the release and exchange of health and medical information, and

J. Ensuring that use of social media and e-health is consistent with the practitioner’s ethical and legal obligations to protect privacy [9].

Beneficence/Nonmaleficence

Beneficence and nonmaleficence are ethical principles that are, in a sense, complimentary to one another. Beneficence indicates that you act in a manner to do good. Nonmaleficence refers to taking due care or avoiding harm. Beauchamp and Childress compare these related principles. Public health professionals are frequently called upon in their daily practice to make both explicit and implicit choices that extend beyond the objective and practical and into the contested and ethical [10]. The obligation to provide net benefit to patients also requires us to be clear about risk and probability when we make our assessments of harm and benefit. Clearly, a low probability of great harm such as death or severe disability is of less moral importance in the context of non-maleficence than is a high probability of such harm, and a high probability of great benefit such as cure of a life threatening dis ease is of more moral importance in the context of beneficence than is a low probability of such benefit [11]. The word nonmaleficence is sometimes used more broadly to include the prevention of harm and the removal of harmful conditions. However, because prevention and removal require positive acts to assist others, we include them under beneficence along with the provision of benefit. Nonmaleficence is restricted to the no infliction of harm.

Fidelity

Fidelity requires that pharmacists act in such a way as to demonstrate loyalty to their patients. A type of bond or promise is established between the practitioner and the patient. This professional relationship places on the pharmacist the burden of acting in the best interest of the patient. Pharmacists have an obligation of fidelity to all their patients, regardless of the length of the professional relationship. In community pharmacy, for example, practitioners have the same obligation to show fidelity to an occasional patient as they have for a regular customer. It is a two-way process with researchers needing to trust research participants as much as participants need to trust researchers. If there is a breakdown in this trusting relationship, there will inevitably be consequences for the quality of the research [12].

Veracity

Veracity is the ethical principle that instructs pharmacists to be honest in their dealings with patients. There may be times when the violation of veracity may be ethically justifiable (as with the use of placebos), but the violation of this principle for non-patientcentered reasons would appear to be unethical. In a professional relationship based upon professional fidelity, patients have a right to expect that their pharmacist will be forthright in dealings with them. Ideally, patients should be asked how much information they wish to know, whether they want others present when test results are disclosed, and what framework they use when they make important decisions. An equal but opposite error to insisting that all patients remain radically autonomous is the assumption that older patients do not object to having their medical information discussed with adult children and other family members [13].

Distributive justice

Distributive justice refers to the equal distribution of the benefits and burdens of society among all members of this society. We often think of distributive justice in terms of our health care delivery system. Even though justice instructs that pharmacists demonstrate an equivalent amount of care, pharmacists do not always provide care with equal fervor to all patients [14]. Sadly, issues such as the patient’s socioeconomic status often impact the level and intensity of care provided by health care professionals. Medicaid patients are sometimes provided a much lower quality of care than a patient who is a cash-paying customer or who has a full-coverage drug benefits plan. All too often, the care provided by a health care professional is viewed in terms of the personal reward for the professional, such as the level of reimbursement the care is likely to reap. Justice demands that the focus be on patients and their medical needs, not on the financial impact on the health care professional. Serious moral criticisms of for-profit health care have been voiced, both within and outside of the medical profession. Before they can be evaluated, these criticisms must be more carefully articulated than has usually been done. The most serious ethical criticisms of for-profit health care can be grouped under six headings. For-profit health care institutions are said to (1) exacerbate the problem of access to health care, (2) constitute unfair competition against nonprofit institutions, (3) treat health care as a commodity rather than a right, (4) include incentives and organizational controls that adversely affect the physician-patient relationship, creating conflicts of interest that can diminish the quality of care and erode the patient’s trust in his physician and the public’s trust in the medical profession, (5) undermine medical education, and (6) constitute a “medical-industrial complex” that threatens to use its great economic power to exert undue influence on public policy concerning health care. Each of these criticisms will be examined in turn [15].

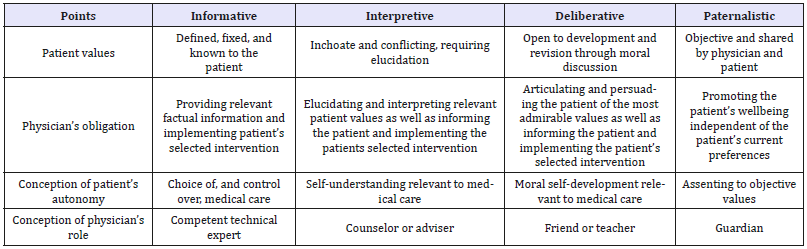

Patient rights varies with culture and social norms In North America and Europe, for instance, there are at least four models which depict this relationship:

A. Paternalistic model: The best interests of the patient as judged by the clinical expert are valued above the provision of comprehensive medical information and decision-making power to the patient.

B. Informative model: By contrast, it sees the patient as a consumer who is in the best position to judge what is in her own interest, and thus views the doctor as chiefly a provider of information.

C. Interpretive model: The aim of the physician-patient interaction is to elucidate the patient’s values and what he or she actually wants, and to help the patient select the available medical interventions that realize these values.

Deliberative model: The aim of the physician-patient interaction is to help the patient determine and choose the best health-related values that can be realized in the clinical situation. To this end, the physician must delineate information on the patient’s clinical situation and then help elucidate the types of values embodied in the available options. The Table 2 compares the four models on essential points. Importantly, all models have a role for patient autonomy; a main factor that differentiates the models is their particular conceptions of patient autonomy. Therefore, no single model can be endorsed because it alone promotes patient autonomy. Instead the models must be compared and evaluated, at least in part, by evaluating the adequacy of their particular conceptions of patient autonomy. The four models are not exhaustive. At a minimum there might be added a fifth: the instrumental model. In this model, the patient’s values are irrelevant; the physician aims for some goal independent of the patient, such as the good of society or furtherance of scientific knowledge [16].

Table 2:Comparison between Physician-Patient Relationship Models.

Special about physician patient relationship

A physician-patient relationship-based paternalism is still deeply rooted in today’s Japan. However, it is also true that “patientoriented healthcare” is beginning to be emphasized in the clinical field here. Demand by patients for the disclosure of medical information is growing year by year. It is expected that physicians have two types of relational skills, namely: instrumental, or the conducts related to the task, and socio-emotional conduct. In the first, questions are made, and information is provided; while in the latter, feelings are addressed, and empathy and commitment are shown. Affective communication between physicians and their patients is characterized by a balance between instrumental conducts and affective conducts, depending on the patient’s specific needs. In recent times, a great deal of factors has been found impacting on the physician-patient communication [17]. The most basic of these have to do with the physician’s gender, given that with the increased number of women in the medical profession, it has been found that women have their patients in mind when making decisions, and they also bear in mind the psychosocial aspects involving their patients. It has been proven that men are more likely to seek direct consultation, to use the medical jargon, and to focus more on physician- type discussions; while women like to talk more with their patients, obtaining better results and diminishing costs [18]. While males speak with a higher, stronger, tone of voice, dominating and competitive, interrupting others, communication from women is more emotional, subjective, and cordial, showing more commitment with the sentiments of others; additionally, the verbal conducts of women are reflected in the nonverbal communication. There is evidence revealing that female medical professionals for the most part express and interpret emotions through non-verbal clues, more precisely than males for example through a smile although there are exceptions.

Ending relationship

The AMA Code of Ethics recognizes that the physician-patient relationship works best when it is a mutually respectful alliance. Termination of the physician-patient relationship is a twostep process. First, identify the behaviors or patterns of behavior that trigger termination. Then provide the appropriate notice of termination to the patient. All decisions affecting the care and treatment of patients are taken within the context of this legal and ethical framework. Pharmacists have the authority to exercise professional and clinical judgment, including the choice to terminate a pharmacist/patient relationship where warranted. Patients are entitled to dignity and respect when interacting with health professionals. The decision to terminate a pharmacist/ patient relationship is a serious one, most often taken because a therapeutic relationship has been compromised and/or there are issues that cannot be resolved and which impact on the ability to provide appropriate pharmaceutical care to the patient. In the language of ethics and the law, a physician may not abandon a patient. Abandonment has been defined as the physician’s unilateral withdrawal from the relationship without formal transfer of care to another qualified physician [19]. However, the ethical obligation of the physician to maintain a relationship with a patient is not without limits. A written communication to the patient regarding a termination of the pharmacist/patient relationship contains the patient’s name [20], the pharmacist’s name and the name of the pharmacy; and additional information including, for example:

A. Affirmation and rationale for the decision to terminate the relationship and date chosen as the last day of care;

B. Direction to the patient to obtain services at another pharmacy and offer to transfer prescriptions;

C. Confirmation that prescriber(s) will be informed of the decision in the event that verbal prescriptions are received, if relevant, and/or a recommendation that the patient inform his/her prescriber(s) directly;

D. Acknowledge attachment of patient profile/medication history (if applicable); and

E. Any other information considered relevant.

Conclusion

The modern world treatment becoming more patient oriented. an individual’s specific health needs and desired health outcomes are the driving force behind all health care decisions and quality measurements [21]. Patients are partners with their health care providers, and providers treat patients not only from a clinical perspective, but also from an emotional, mental, spiritual, social, and financial perspective. The todays literature about patient care is telling many more things, like facts of patient care benefits, role of pharmacists or other caregivers to a more patient centric approach. But the very basic lies with the provider patient relationship where professionalism and ethics plays massive role. If any the conduct is uncared or overlooked, the total effort will be in vain.

Acknowledgement

It’s a great gratitude and honor to be a part of healthcare research and education. Pharmacists of all disciplines that I have conducted was very much helpful in discussing healthcare providers ethics and professionalism, providing books, journals, newsletters and precious time [22]. The greatest help was from my students who paid interest in my topic as class lecture and encouraged to write such article comprising all ethical aspects in pharmacy profession. Despite a great scarcity of funding this purpose from any authority, the experience was good enough to carry on research.

References

- APhA (1995) Code of ethics for pharmacists. American Pharmaceutical Association. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 52: 2131.

- Snyder JE, Gauthier CC (2008) Evidence-based medical ethics© human press, Totowa, New Jersey.

- Hiroyasu, GOAMI (2007) The physician-patient relationship desired by society 259. Japan Medical Association Journal 50(3).

- Satyanarayana Rao KH (2008) Informed consent: an ethical obligation or legal compulsion? J Cutan Aesthet Surg 1(1): 33-35.

- Annie Cushing, Richard Metcalfe (2007) Optimizing medicines management: From compliance to concordance. Ther Clin Risk Manag 3(6): 1047-1058.

- John Paling (2003) Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ 27: 745-748.

- Sandra Petronio, Mark J DiCorcia, Ashley Duggan (2012) Navigating ethics of physician-patient confidentiality: a communication privacy management analysis. Perm J 16(4): 41-45.

- Ray Noble (2007) Introduction to medical ethics center for reproductive ethics and rights UCL institute for women’s health London, 31.

- (2014) Good medical practice: A Code of conduct for doctors in Australia code of conduct | Pharmacy Board of Australia.

- Peter Schröder-Bäck, Peter Duncan, William Sherlaw, Caroline Brall, Katarzyna Czabanowska et al. (2014) Teaching seven principles for public health ethics: towards a curriculum for a short course on ethics in public health programmes. BMC Med Ethics 15: 15-73.

- Gillon R (1994) Medical ethics: four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ 309(6948): 184-188.

- Leslie Gelling (2015) Fidelity: the third ethical principle.

- Joal Hill (2003) Conduct and compassion veracity in medicine. THELANCET 362(9399): pp1944.

- Amy Haddad (1996) Ethical dimensions of Pharmaceutical Care In: Amy Marie Haddad, Robert A Buerki (Eds.), Pharmaceutical Products Press, New York, pp. 115.

- Dan W Brock, Allen Buchanan (1986) Ethical issues in for-profit health care for-profit enterprise in health care. NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS US 225.

- Ezekiel J, Linda L (1992) Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA 267(16): 2221-2226.

- José HO (2011) Evolution and changes in the physician-patient relationship. Colomb Med 42(3).

- Julie Schmittdiel MA, Kevin Grumbach, Joe V Selby, d Charles P Quesenberry, et al. (2000) Effect of physician and patient gender concordance on Patient Satisfaction and Preventive Care Practices. J Gen Intern Med 15(11): 761-769.

- The practice guide: medical professionalism and college policies ending the physician-patient relationship the college of physicians and surgeons of Ontario 80 college street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- (2016) Physicians committee human experimentation: an introduction to the ethical issues.

- Clinical governance in drug treatment (NHS) A good practice guide for providers and commissioners Web: Clinical governance in drug treatment-Emcdda, Europe.

- Code of Conduct for Registered Practitioners.

© 2019 AK Mohiuddin. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)