- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Applications in Pharmacy & Pharmacology

Video and Animation Both Prove useful for Pharmacy Communication Training

Hayley Croft*1, Rohan Rasiah1, Keith Nesbitt2 and Joyce Cooper1

1 Faculty of health and medicine, Australia

2 Faculty of science and IT, Australia

*Corresponding author: Hayley croft, Faculty of health and medicine, Australia

Submission: December 06, 2018;Published: December 19, 2018;

ISSN 2637-7756Volume2 Issue3

Abstract

Objective: To compare the effectiveness and student experience of video versus animation for teaching communication skills in patientpharmacist interactions.

Methods: A cohort of first year Pharmacy students were randomly divided into two equal groups. The first group watched a series of three video scenes each depicting a patient-pharmacist interaction, and completed a questionnaire aimed at evaluating identification of communication strategies used in each of the scenarios. This group then watched the same three scenes as an animation. The second group followed a similar protocol, except they experienced the animation first, followed by the video. An evaluation survey was completed by both groups at the completion of the animations and video scenarios to measure any difference in preference between video and animation. The research investigated two questions. Firstly, are there any differences in the ability of students to identify key communication competencies using video versus animation? Secondly, do first year Pharmacy students perceive a difference in the usefulness of animation compared to video for communication skills training?

Results: Both the video (85%) and animation (84%) were equally effective for demonstrating key communication elements and behaviors. In both cases students were able to self-identify an improvement in their own communication knowledge. Most students (75%) also agreed that both the video and animation approaches provided a stimulating, realistic and useful way to depict a customer-pharmacist communication encounter. Although, after experiencing both the video and animation scenarios, the majority of students (73%) identified a preference for the video.

Conclusion: Both the video and animation provided an effective and positive approach to communication training. Advances in video and animation technology provide an opportunity to extend the range of tools used for communication skills training within the pharmacy curriculum.

Keywords: Communication; Information technology; Animation; Video; Simulation; Pharmacy; Students; Education

Introduction

Advances in information technology (IT) now support a broad range of delivery modes for teaching and learning of interest are technologies that improve the flexibility, effectiveness, efficiency and scalability of online materials of interest is the use of video and animation for teaching communication skills to pharmacy students. Effective communication between a pharmacist and a patient is crucial to optimal patient care [1]. To meet their professional responsibilities, pharmacists require proficiency in interpersonal communication, and is a core competency of the profession [2]. Despite this priority, difficulties have been identified around designing curricula that utilize activities that are effective in promoting competency in communication skills [3]. The literature indicates that in recent decades, traditional classroom methods have been the mainstay for teaching communication skills in pharmacy curricula [4]. However, theory-based information, typically delivered in a lecture setting, often fails to incorporate the appropriate depth of engagement required for learning interpersonal communication [4]. More recently, role-play and the use of simulated or standardized patients are more common activities used to immerse students in the complexity and diversity of communication scenarios encountered by a pharmacist [3,4]. Providing placement in a pharmacy setting is an alternate strategy used in pharmacy schools. However, the capacity of a curriculum to support communication training in authentic settings, requiring several people (e.g. trained actors) and locations, can be time consuming, costly and restrictive [5].

A systematic review in 2013 found that an integration between different learning activities was important if communication training was to succeed [3]. Furthermore, progressive use of new technologies was also considered a key factor [3,6]. Across the pharmacy curriculum there is increasing research showing various educational technologies being used by student pharmacists, with the evidence indicating a positive impact on learning.6 For example, virtual practice environments have been more recently used to develop communication skills in pharmacy students. In a study conducted in 2012, life-sized photographic and video images were used to develop a virtual environment. This environment was reported to be both engaging and aesthetically pleasing, whilst providing an effective context for developing communication skills in students [4]. It is becoming easier for educators without expertise in IT to incorporate new media, such as video, animation and computer games into teaching programs. However, the cost of introducing these types of content may still prove expensive to produce. Therefore, it is appropriate to investigate further the advantages and disadvantages of specific technologies that might be involved in delivering communication scenarios for pharmacy education [6].

Video recording of a simulated communication scenario is one approach that supports reuse and allows for flexible online delivery. The lower cost of equipment and wide access to simple editing tools means video can be quickly produced even without extensive knowledge in film-making. Video also provides a suitable replacement for real-time simulation [7]. On the downside however, producing a video may require effective training of actors to act as simulated patients, particularly if the presented scenarios are to provide a enough level of realism. Furthermore, a good quality video, which relies on expertise in production and postproduction, can still be expensive to produce. Once completed it can be difficult to update videos which can quickly become dated, adapt dialog or change scenes or alter emphasis for different audiences [7]. By contrast, video animation can be more readily updated and does not require trained actors or a large supporting group to be involved in the production. Animation offers greater flexibility in its ability to alter images and therefore may afford better reuse compared to videos with actors [8]. While hand-drawn animation has traditionally been expensive to produce, this cost might be reduced in the future by leveraging new IT technologies that automate animation processes [9]. Continuing advances in the technology of animation could enable the design of communication scenes that replace the actors with realistic animated characters. While the literature shows there is increasing use of IT for creating training simulations, there is little research that shows how realistic the computer graphics need to be for the learning activity to meet its objectives. It is furthermore unclear, what animation means in terms of student acceptance and effectiveness.

The motivation behind our research is to determine if innovations in IT provide an appropriate level of student engagement and if they can be applied to assist in the teaching of communication skills to pharmacy students. In this paper we investigate the specific use of video and animation for contextualizing pharmacist-patient roleplaying scenes. The study is guided by two key research questions. Firstly, are there any differences in the ability of students to identify important communication behaviors when viewing the video versus the animation? Secondly, is there any difference in the level of student acceptance or perceived usefulness for video versus animation for teaching communication skills?

Methods

Communication scenarios-design

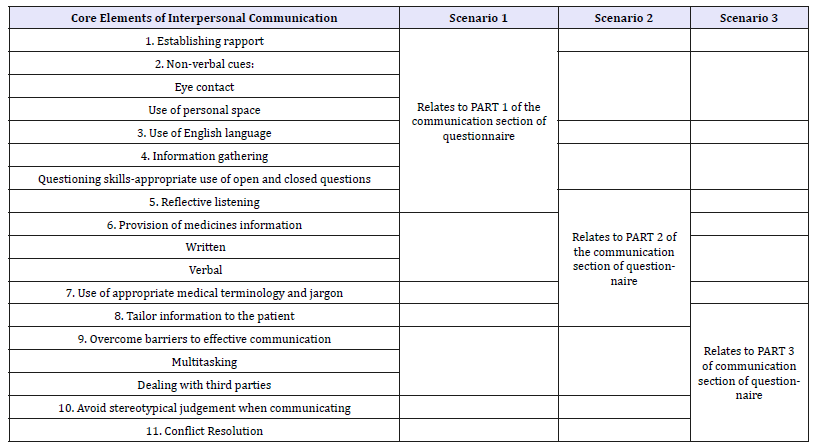

A specific communication encounter between a pharmacist and two customers was designed based on the over-the-counter supply of emergency hormonal contraception. The encounter was divided into three scenarios, with the complexity of the communication increasing with each scenario (Table 1). The communication skills depicted in the scenarios is consistent with that taught in the Pharmacy Program at the University of Newcastle (Table 2). The design of the scenarios also incorporated the eleven compulsory national competencies for communication required by pharmacists in Australia [2]. These eleven competencies were also used to assess and evaluate the student’s ability to recognize key communication elements in the video and animation. The competencies are detailed in Table 2.

Table 1:Summary of patient-pharmacist interaction in the three scenarios.

The scenarios were scripted and workshopped with trained actors and pharmacy education experts. A mental health expert validated the behavior of the encounter. The three scenarios were filmed in a community pharmacy. Trained actors played their roles under the supervision of an experienced director and pharmacy education experts. During post-production the full patient-pharmacist interaction was edited into three short, linked communication scenarios, whereby each scenario builds on the previous one. Each of the three scenarios was approximately two minutes in length. Appropriate color correction and sound equalization were used to ensure consistency between the videos Figure 1.

To generate the animated version of these scenarios, the final videos were further processed in Adobe After Effects by using cartoon effects and posturized time filters, with further color correction. This produced a replica of the same three video scenarios with the exception that the people and the pharmacy environment appeared visually abstracted and moved with a reduced frame rate typical of hand-drawn animation Figure 1.

Figure 1:Summary of patient-pharmacist interaction in the three scenarios.

Questionnaire design

Table 2:Communication competencies used to design and evaluate scenarios.

Figure 2:Communication competencies used to design and evaluate scenarios.

A comprehensive questionnaire (available from the corresponding author by request) was designed to provide a means of openly gathering attitudes, emotions and experiences of participants as well as measuring relevant communication knowledge [10,11]. The survey tool was designed in four sections; a demographic section, a communication section, a usability section and a comparison section. We designed the demographic section to be administered prior to watching the three scenarios. It contained four limited answer questions related to gender, language, pharmacy and technology experience. The communication section of the survey tool was intended to measure how well students were able to detect the relevant communication cues and skills in each of the three scenarios. Participants were asked to observe the interaction between the patient and pharmacist in each scenario and then select which of the multiple-choice statements applied to the communication skills displayed by the pharmacist. Each multiple-choice question had four possible responses, of which only two were considered correct. Students were scored on their ability to identify one of the two correct responses from each of the six multiple-choice questions. These multiple-choice questions and three further open-ended questions were related directly to the core competency skills depicted in that specific scenario (Table 2).

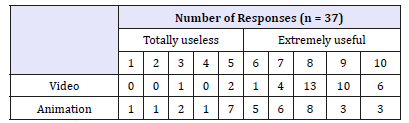

The usability section was based on a Likert scale and contained five closed questions consisting of five alternatives that described a range of possible answers from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” [12]. It was intended that this usability section, relating more generally to the entire three scenarios would be completed immediately after the final scenario. The questions in this section were designed to measure the perceived usefulness of the scenarios for teaching communication skills. At this stage students would only have experienced one of the forms of presentation. The usability survey also provided the opportunity, through two open questions, to identify what students liked about the presentation style and conversely, what might be improved. The usability section of the survey completed the within-groups study of the video and animation treatments. The final part of the survey tool was the comparison section. This section was completed after students had had the opportunity to watch both the video and animation versions of the scenarios. It was intended to gather student perception about which style of presentation, if any, they preferred. It consisted of a limited answer question to identify preference, and two questions that allowed students to rank the usefulness of 1. the video and 2. the animation on a scale from totally useless [1] to extremely useful [10].

Student participation

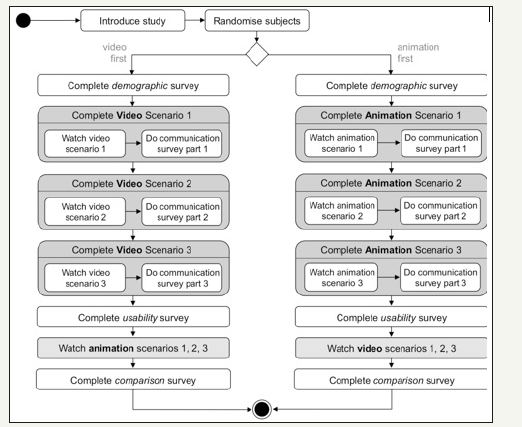

Following the development of the video and animation scenarios, students enrolled in the Pharmacy program were invited to participate in the study. The study took place in the second half of a non-compulsory two-hour pharmacy practice tutorial session. The University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study. After a brief introduction to the study, the participants were randomly assigned to two groups, in separate tutorial rooms. Both tutorial rooms were identical and contained a large display on which the video and animations were projected. The two groups first completed the demographic survey section before watching the three scenarios as either video or animation. One group watched the sequence of three video scenarios (n=17), answering the relevant part of the communication survey after each scenario. The second intervention group (n=21) watched the animation scenarios, again answering the relevant part of the communication survey after each scenario. Apart from any reference to “video” or “animation” the questions completed by each group were identical.

At the completion of the third scenario, students completed the usability section. For students who watched the video scenarios first this referred to the usability of the video, while for the students who watched the animation first this would reference the usability of the animation. After the usability section, students watched the three alternative scenarios. Thus, students who had watched the video first, now watched the animations, and students who had watched the animations first now watched the videos. The three scenarios were presented in the same order but with only a minimal break between each of the scenarios. On completion all students were instructed to complete the final comparison survey. The completed surveys were collated to maintain student anonymity whilst still allowing the answers to be considered in relation to the demographic data. The process used in the experiment is shown in Figure 2.

Results

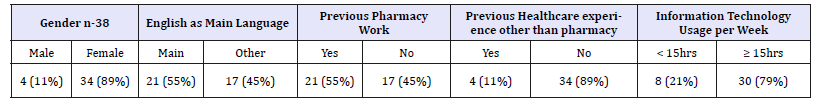

Table 3:Summary of demographic data.

Thirty-eight students participated in the study. A summary of participant demographics is shown in Table 3.

Identification of communication behaviors using video and animation technologies.

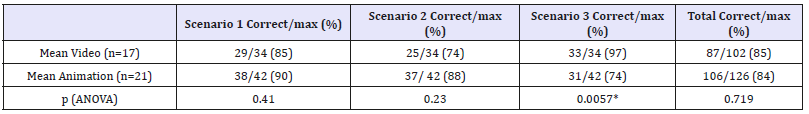

The numbers of students correctly identifying the communication competencies for each scenario are shown in (Table 4). The data collated from this component of the survey was normally distributed and the standard deviation of both groups was approximately equal. A one-way ANOVA was performed on the mean result from the video and animation considering each of the three scenarios as well as the overall total (Table 4). The average mark for the animation group was 84% and the average mark for the video group was 85%. In both groups, 71% (n=12/17 and 15/21) of participants were able to identify at least five correct statements out of six questions in relation to communication knowledge. For Scenario 3 alone there was a significant difference found, with less students being able to identify key communication elements when using the animation. However, overall there was no significant difference in students being able to identify key communication elements between the animation group and the video group (F1, 36=0.13, p>0.5).

Table 4:Percentage of correct responses identifying key communication skills.

As part of the communication section of the survey, students also completed three open questions asking for general comments as well as what they thought the pharmacist did well and where they may have improved on their communications. The responses for both the video and animation groups were analyzed to try and identify any differences in relation to the comments made about communication aspects of the scenarios. Students who watched the animation and video generally attended to the same ideas, with no noted differences between the video and animation groups. Both groups demonstrated an ability to identify emotions that the pharmacist showed; reflect on the choice of words and language the pharmacist had used to speak with the patient; consider the barriers to communication that the pharmacist had to overcome; and use words to describe the overall feeling of the interpersonal aspects of communication. For example, students who watched the animation reflected that the pharmacist was “clear, concise and calm” and “asked appropriate questions”. This group of students also identified that the pharmacist was good at “building rapport with the patient”. Students who watched the video commented that the pharmacist “responded to questions and patient concerns well” and ‘remained clam when distractions developed”. Furthermore, students in both groups offered wide-ranging ideas for how they think the pharmacist could improve on their communication. For example, “show more concern and empathy towards the patient”, “show more support through gestures and facial expressions”, “use a more private area for counselling”, “show more assertiveness” and “simplify language when communicating about adverse effects” Table 5.

Table 5:Video and animation usability results.

Usefulness of video versus animation

In terms of the way students perceived the technology, most students (75%) agreed or strongly agreed that the use of the video/ animation stimulated their interest to learn about communication skills, and that both technologies provided a useful teaching resource when compared with other methods for communication training such as lectures and role-plays. Furthermore, participants clearly indicated that they thought both the video and animation were able to present a realistic patient-pharmacist encounter, and that the images did not distract from being able to identify and comment on communication issues. Regarding the acceptance of both video and animation technology both groups suggested that the two approaches were able to present a realistic patient-pharmacist situation. For students who watched the video scenarios, comments included “it was a very realistic way of simulating scenarios in a real pharmacy” and “it portrays a good patient-pharmacist interaction”. Very similar comments were noted from students in the animation group, who described the animation as a “real-life situation” and wrote “I found it surprisingly realistic despite the fact that it was animated”; and “it was a real-life experience that includes emotions” Table 6.

Table 6:Comparative data post-crossover.

One key difference between the two groups were the comments made by students in the animation group who suggested that improved image quality would make the scenarios more realistic and that this would be an improvement on the use of this technology for future communication training. There was also a single comment that indicated the “animation was very distracting” and that regular imaging would be preferable.

Students from both groups made positive comments relating to the perceived effectiveness and usefulness of the technology for communication skills training, indicating that they would like to see this approach used more often. A participant from the animation group suggested it should be “used more during the pharmacy course”, with another student stating that animation “definitely mimics a real-life situation and would be beneficial as a learning tool”. Students commented that they were able to consider components of their own communication skills that needed improvement. One student commented that they were “able to identify issues in communication where I feel short based on the animation”. Another student who watched the animation said it was “good to see where I am lacking in communication”. A positive comment was provided about the videos, suggesting it “will help a lot in placement” following up with the idea that these scenarios would assist with preparing students for placements.

A number of comments suggested that students would like to see a wider range of patient-pharmacist interactions that focus on different aspects of communication, encompass more varied health topics, different health settings, different patient demographics; and even, comparing the way different pharmacists approach the same situation. For example, suggestions for improvement in both groups included “hospital setting scenarios”, “communication with doctors”, “various pharmacy topics”, “different medications” and “different approaches to the same scenario”. Students commented that a ‘debriefing’ session with the tutor afterwards would add to their learning experience.

Final evaluation of comparison of video versus animation

In the final comparison survey, 73% (n=27/37) of respondents had a preference for the video and 3% (n=1/37) had a preference for the animation, as their preferred delivery for communication training. 24% (n=9/37) identified no particular preference for either the video or animation. Respondents were also asked to rate how useful each approach would be to communication training on a scale of 1, representing totally useless, to 10, representing extremely useful. This produced a statistically significant result, with an average of 8.1/10 for video compared to an average of 6.5/10 for animation. (ANOVA F1, 35=13.3, p< 0.05).

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness and perceived usefulness of video versus animation in teaching communication skills to pharmacy students. This was achieved by evaluating students’ experiences with a typical pharmacistpatient scenario presented both as video and animation. In general, the study showed that there was no overall difference in student ability to interpret the embedded communication elements when presented as video or animation. While students performed better by identifying more of the communication competencies with the video presentation in the third more complex scenario, it is not clear why this difference occurred. This may be a limitation of the study and due to an artefact in the way we measured communication effectiveness. Indeed, this is an area that has been traditionally difficult to measure. As [3] describes, subjective measures of assessment have been used in many studies, which makes it difficult to prove communication skills have been adequately acquired [3]. Since communication is a difficult area to judge, objective measurement of student’s abilities is largely dependent on fair and skilled evaluators [3]. Another suggestion is that we noted that the automated animation process may have removed some detail in terms of lip movement of the actors in this third scenario. It has been well reported that not being able to clearly see a person’s lips move can detract from a person’s ability to understand speech [13,14]. While this might raise a potential criticism of the process used to create the animations used it does not raise significant concerns of the general animation approach.

However, this does also raise an important point about the style of animation. There are many approaches to making an animation, all capable of producing a different look and feel, which include hand-drawn animations, or computer-generated 2D and 3D animations, which have different production steps and associated cost factors. Of course, the same can be said for video where the quality and style of presentation can similarly impact on quality, cost and suitability. In terms of animation we are anticipating that trends in IT will greatly reduce the cost of producing animations and make further simple automated production tools available to educators. Hence our aim in this study was to compare the two approaches in general, using presentations that were as comparable as possible.

The usability questions in the study identified no obvious differences in the perceptions of students towards each of the methods of communication skills training. After being exposed to only one technological approach-the video or the animation, the two student groups agreed that each of the approaches used for teaching communication was stimulating, realistic and useful. Importantly we believe that animation lends itself to greater flexibility in updating and altering a scenario. For example, in a computer-generated animation we might easily change the look of the pharmacist or patient. Interestingly however, once being exposed to both approaches, only 24% of the students considered the animation and video to be equally useful with 73% of the students identifying a clear preference for the video. The survey did not explicitly ask students to expand on this response and this is one improvement we will make in future studies. Focus groups may also provide an opportunity to gathering information about why students had a particular preference for one technology approach over another.

Overall our findings indicate that advancing animation technology may offer potential alternatives to simulated actors and role-plays in creating options for diverse and flexible professional learning experiences. The ‘Media Equation [15] provides some insight into this phenomenon, as it predicts that animation should be just as effective as video in terms of communicating. It also claims that people have a strong tendency to respond to media and computers as if they were real people and real places. This result is similar to those reported from students who used a virtual practice environment for communication skills training and agreed that the visual and aural computer and video graphics were able to successfully create an atmosphere that represented a pharmacy environment, and in addition students are willing to suspend disbelief and assume reality for the purpose of immersing themselves in a learning experience [4].

Conclusion

Teaching communication skills is an important education component across a number of disciplines, including pharmacy. It provides a number of challenges in the ability to provide engaging and stimulating ways to learn about and practice communication skills that require critical thinking, responsiveness and focus. It is these challenges that motivated us to investigate the possibility of using animation to effectively teach communication skills in a more flexible manner. Advances in IT, particularly in video production, animation, and associated game technologies, provide an opportunity to investigate novel approaches to teaching communication skills. This is especially relevant in areas where more flexible online and cost-effective approaches may be required. The specific purpose of this research was to investigate the effectiveness and student acceptance of video versus animation for teaching communication skills to pharmacy students. In this study we developed three, linked communication scenarios based on a typical pharmacist-patient interaction. The scenarios were designed to incorporate the eleven core competency skills required of Australian pharmacists. These scenarios were filmed in a community pharmacy and then produced to create both video and animated versions of the three scenarios. Overall, students were just as effective in identifying the core communication skills in both versions. Prior to experiencing both the video and animation scenarios, students felt equally positive about the use of both approaches, indicating they were able to present a stimulating, realistic and useful communication encounter and that they demonstrated key communication elements and behaviors.

After experiencing both styles of presentation students expressed a clear preference for the video rather than the animation. The reason for this preference requires further investigation. Despite this, we conclude that animation is an equally valid way to imitate, model and teach pharmacy communication and that it is able to provide students with exposure to what they are likely to encounter in professional practice. Indeed, students reported that they would like to see a wider range of topic areas, covering more difficult and complex communication scenarios that they are likely to encounter on placement and in practice. Students in both groups also agreed that learning about communication by watching video and animated scenarios could be improved with a debriefing or follow up discussion with the tutor afterwards. This would allow them the opportunity to discuss aspects of the encounter and to share thoughts and ideas with other participants and receive feedback from the facilitator. We know that video and animationbased modules can be delivered simply in an online environment [9]. However, further research is necessary to determine the relative effectiveness, cost, flexibility and student acceptance of these different approaches. The results from this study provide no strong evidence that animation should not be equally effective as video in teaching communication. We also believe that animation has some advantages as it lends itself to achieving greater flexibility in terms of updating and altering scenarios and this situation will only improve with ongoing advances in available technologies.

References

- Beardsley RS, Kimberlin CL, Tindall WN (2007) Communication Skills in Pharmacy Practice, (5th edn), Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA.

- PSA (2014) National competency standards framework for pharmacists in Australia. Pharmaceutical Society of Australia.

- Wallman A, Vaudan C, Kalvemark S (2013) Communications training in pharmacy education, 1995-2010. Am J Pharm Educ 77(2).

- Yasmeen Hussainy S, Styles K, Duncan G (2012) A virtual practice environment to develop communication skills in pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ 76(10): 202.

- Smith D, McLaughlin T, Brown I (2012) 3D Computer animation vs. liveaction video: differences in viewers’ response to instructional vignettes. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 12 (1): 41- 54.

- Stolte SK, Richard C, Rahman A, Kidd RS (2011) Student pharmacists’ use and perceived impact of educational technologies. Am J Pharm Educ 75 (5): 92.

- Makary M (2013) The power of video recording taking quality to the next level. The Journal of the American Medical Association 309(15): 1591-1592.

- Parent R (2012) Computer animation. Algorithms and Techniques, (3rd edn), Elsevier, USA.

- Vince J (2000) Essential computer animation fast. In: What is Computer Animation? Great Britan Springer-Verlag, London, UK.

- Gaebelein C, Gleeson B (2008) Critical appraisal of evidence derived from cohorts and surveys. In contemporary drug information. An Evidence Based Approach Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, pp. 160-163.

- Robson C (2011) Surveys and Questionnaires. In Real world research: a resource for users of social research methods in applied settings, (3rd edn), Chichester, England, UK, pp. 237-277.

- Allen E, Seaman CA (2007) Likert Scales and Data Analyses. Quality Progress 40: 64-65.

- Sumby WH, Pollock I (1954) Visual contribution to speech intelligibility in noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 26: 212.

- Erber NP (1975) Auditory-visual perception of speech. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 40: 481-492.

- Reeves B, Nass C (1996) How people treat computers, television, and new media like real people and places. The Media Equation CSLI Publications, California, USA, pp. 3-15.

© 2018 Hayley Croft. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)