- Submissions

Full Text

Journal of Biotechnology & Bioresearch

A Piece of History and Botanical Issues of Tulips

Shukrullozoda Roza Shukrullo Qizi* and Khaydarov Khislat Kudratovich

Department of Botany, Samarkand State university, Uzbekistan

*Corresponding author:Shukrullozoda Roza Shukrullo Qizi, Department of Botany, Samarkand State university, Uzbekistan

Submission: December 12, 2022;Published: February 06, 2023

Volume4 Issue3February , 2023

Abstract

This article summarizes the history of tulips taxonomy from the distant past to the present, in relation to their grouping and dividing them into botanical structures, and about the history and botany of tulips.

Keywords: Chemical constituents; Flowering process; Nectaries; Phytopathological base

Introduction

The tulip is the main ornamental flowering bulb. According to [1] statistics for 1974 numbered about 9,400 ha. annually. This amounts to several billion bulbs. Besides, tulip is a complex plant having an integrated series of growing and aging organs (Figure 1,2). Following this, it presents a problem not only for bulb growers, law enforcers and gardeners, but also for applied and main scientists [1]. Although reviews have been [2-4], books [4,5], mandatory manuals [6-9] and three international symposiums on flower bulbs [10,11] (Rees and van der Borg, 1975), in which discussed various aspects of the tulip, never had the review is devoted exclusively to the tulip. Our goal is to cover all important areas related to botany, use, growth and tulip development. In many areas there are well-documented research base, such as the flowering process. Thus, we have presented personal observations or unpublished studies when appropriate.

Botanical classification, distribution and description

Tulips belong to the genus Tulipa L (Liliaceae). According to Cronquist [12], Liliaceae are placed in the division Magnoliophyte, class Liliopsid, subclass Laridae and order Lili ales. The diversity of tulips varies 40-120 species [13] that usually grow in high heigh altitude habitats [14]. The distribution area is from the Mediterranean through Asia to Korea and Japan [15- 18]. Bailey [15] describes tulips as follows: plants derived from bulbs are sheathed, mostly tapering upwards (toward the “nose”), with fleshy scaly leaves; with a stem-like petiole that bears leaves; lonely and simple, sometimes branched, sometimes multiple; three to five leaves; flowers hypogynous, erect, bell-shaped to saucer-shaped; six perianth segments distinct, without nectarines; six stamens included basis fixed; column one- or two-leaved (most garden varieties), stigma three-lobed; the fetus is a tricuspid loculicidal box; and seeds numerous, flat. Tulips usually differ from other bulbous genera in that family with erect flowers, usually with six perianth lobes (tepals), six anthers and one style with a three-lobed stigma. This is a typical image of a garden tulip. However, there is great variability not only between species, but also within more than 2000 varieties resulting from breeding and breeding (Kon. Alg. Ver. Bloembollencultuur 1981). So, there are tulips with more than six perianth parts of various shapes, with plumage or perianths fringed, with more than six anthers and with multiple and branched petioles with several flowers. Cultivated tulips were divided into 15 groups based on< during flowering in the open field, the morphology of the perianth parts and their origin. It should be noted that although in 1981 classification gives 15 groups, there have been big changes from the previous 15 groups (Kon. Alg. Ver. Bloembollencuhur 1976). Mendel’s tulips have been classified as Triumph; the only latecomer class now includes Darwin and Cottage tulips; and two new classes Fringed tulips and Variciform tulips have been added. Varieties provide a wide range of perianth colors other than true black or blue. There are red, pink, white, lavender, and yellow varieties, among others. with a solid base color and edge-dyed, flamed and/ or striped. The last type of variation can be caused by viruses [18] and this was a contributing factor to the “tulip mania” that occurred in the Netherlands in the 1600s [19,20]./p>

Basic morphology, anatomy, growth and development

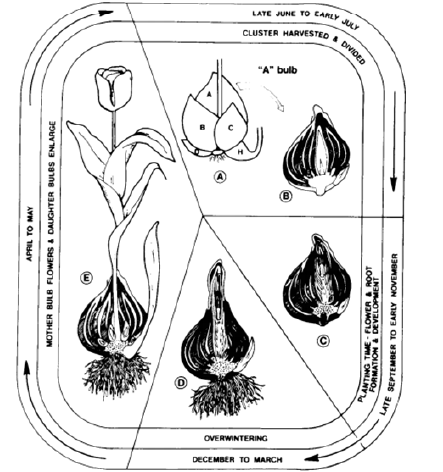

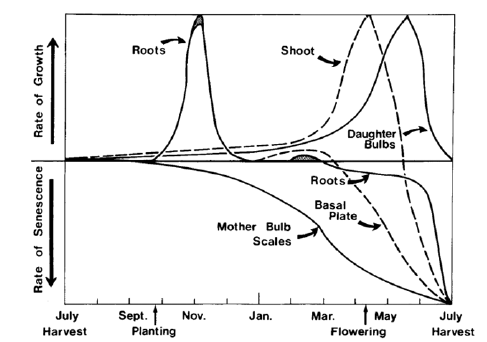

General characteristics. Tulip bulbs are obtained from seeds [16] that come from the fruit box. Seeds after harvest contain an immature embryo that is in “embryonic rest” and requires minimum 40-50 days at 4 °C to achieve full development (Niimi 1978, 1980). An additional period of 30 days at 4 °C was necessary for germination and subsequent seedling development. As described in Section II.H, it takes 4-6 years to reach flowering. The annual cycle of growth and development of a blooming tulip the light bulb is shown in Figure 1 and 2. This section will briefly describe general morphological, anatomical and evolutionary changes various organs. Specific changes in the production and forcing of bulbs are discussed in Sections I11 and IV.

Figure 1:Annual growth and development cycle of a flowering tulip

(a) harvested cluster;

(b) separated “a” blub;

(c) mother blub with developed root primordia and shoot prior ro planing;

(d) rooted blub in overwintering environment;

(e) mother blub at anthesis, small shoot is “h” blub [27].

Figure 2:Annual growth and senescence changes of major organs of a flowering tulip [27].

Tulip Bulb Forcing

General aspects

The normal forcing season for tulips runs from early December to mid-May, and many factors must be considered for successful forcing. Key tasks are the prevention of abortion of flowers, optimization of commercial height, make the flower harvest evenly, force a reasonable amount days in the greenhouse and optimize the size of flowers and leaves. All used techniques based on the annual cycle of growth and development of the tulip (Figure 1,2). Awareness of the interaction of the environment on this cyclical process with particular attention to flowering the process is essential. From a commercial point of view varieties [7-9] is important. Some varieties of tulips cannot be bred, and those that can have optimum distillation and use time.

Bulb size has been found to be critical for flowering. process [3]. In addition, the size of the flower depends on the size of the bulb. and the larger the bulb, the larger the flower. Therefore, for commercial forcing only 11/12cm and bulbs 12/up cm are used with 11/12cm Bulbs are primarily cut for late forcing. Another bulb size effect seen in some varieties is the “Anchylose” disease [21]. This is a real example of blindness. Full sheet Complement is formed but flowering is not initiated. It’s been seen in bulbs 16/18cm varieties “Apricot Beauty”, “Demeter” and “Yokohama”.

Forcing techniques

The standard forcing method is based on normal sequence summer-autumn-winter-spring. It may include up to 6 weeks of pre-cooling at 7 or 9 °C, provided that the bulbs have reached or passed stage G. These lamps are designed for early compulsion. Bulbs without pre-cooling are used for medium and late forcing. Whether they have been pre-chilled or not, all bulbs are initially rooted at 9 °C compromise temperature between optimum temperature for rooting [22] and cooling [23]. During low temperature programming, the temperature must be reduced to 5 °C after the roots have reached a length of at least 5cm. When or if shoots reach 5cm, the temperature in the rooting room should be reduced to W-1 “C to slow down the growth of shoots.

Conclusion

Pioneering Dutch exploration of Balaua in Wageningen and Van Slaughtermen et Lises and colleagues presented a robust physiological analysis and Phyto pathological base for commercial production of tulip bulbs and forcing during the 1950s Subsequently, a large number of publications became available [7- 9,21,24-27]. In addition, over the past two decades there have been significant increases not only in knowledge related to endogenous and exogenous growth regulators, chemical constituents and metabolism, but also in improved methods of bulb production and forcing. Nonetheless the tulip is very complex and a lot of research needs to be done to fully understand the mechanisms that control overall growth and bulb development. Finally, we want to point out that although we have cited many published reports and articles, a more comprehensive bibliography is maintained [28-32].

References

- Kronenberg HG (1977) Tulip bulb production potentials in Europe. Neth J Agric Sci 25: 229-237.

- De Hertogh AA (1974) Principles for forcing tulips, hyacinths, daffodils, Easter lilies and irises. Scientia Hort 2: 313-355.

- Hartsema AM (1961) Influence of temperatures on flower formation and flowering of bulbous and tuberous plants. In: Ruhland W (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology 16: 123-167.

- Rees AR (1966) The physiology of ornamental bulbous plants. Bot Rev 32: 1-23.

- Larson RA (1980) Introduction to floriculture. Academic Press, New York, USA.

- Bing A (1971) Cut tulips for commercial growers from dry-stored bulbs. Cornell University Ext. Bul. 1221, USA.

- Buschman JCM, FM Roozen (1980) Forcing flower bulbs. International Flower-Bulb Centre. Hillegom, Netherlands, Europe.

- De Hertogh AA (1981) Holland bulb forcers guide. (2nd edn), Netherlands Flower-Bulb Institute, New York, USA.

- Ministry of agriculture, fisheries and food (1977) Tulip bulb production. Booklet B2298, England, UK.

- Bergman BHH, Eijkman AJ, Van Slogteren DHM, Timmer MJG (1971) First international symposium on flower bulbs. Acta Hort 23: 440.

- Rasmussen E (1980) Third International Symposium on flower bulbs. Acta Hort, p. 109533.

- Cronquist A (1968) The evaluation and classification of flowering plants. Houghton Mi Min Co, Boston, USA.

- Dekhkonov D, Tojibaev KS, Makhmudjanov D, Nuree NA , Shukherdorj B, et al. (2021) Mapping and analyzing the distribution of the species in the genus Tulipa (Liliaceae) in the Fergana valley of Central Asia. Korean J Pl Taxon 51(3): 181-191.

- Dekhkonov D, Tojibaev K, Yusupov Z, Makhmudjanov D, Asatulloev T (2023) Morphology of tulips (Tulipa, Liliaceae) in its primary centre of diversity. Plant Diversity of Central Asia.

- Bailey LH (1949) Manual of cultivated plants. MacMillan Company, USA.

- Botschantzeva ZP (1982) Tulips: Taxonomy, morphology, cytology, phytogeography, and physiology. In: Varekamp HQ, Balkema AA (Eds.), Rotterdam, Netherlands, Europe.

- Dekhkonov D, Asatulloev T, Tojiboeva U, Idris S, Tojibaev SK (2022) Suitable habitat prediction with a huge set of variables on some Central Asian tulips. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity.

- Tojibaev K, Dekhkonov D, Ergashov I, Sun H, Deng T, et al. (2022) The synopsis of the genus Tulipa (Liliaceae) in Uzbekistan. Phytotaxa 573(2): 163-214.

- Cohen M (1981) Beneficial effects of viruses for horticultural plants. Hort Rev 3: 394-411.

- Lodewijk T (1978) The book of tulips. Vendome Press, New York, USA.

- Schenk PK (1971) Diseases and abnormalities in bulbous plants. Liliaceae. N.V. Nauta and Co's Drukkerij, Zutphen, The Netherlands, Europe, Volume 1.

- Jennings NT, De Hertogh AA (1977) The influence of pre planting dips and post planting temperatures on root growth and development of non-precooled tulips, daffodils and hyacinths. Scientia Hort 6(2): 157-166.

- Rees AR, Turquand ED (1969) Effects of planting density on bulb yield in the tulip. J Appl Ecol 6: 349-358.

- Gould CJ (1957) Handbook on bulb growing and forcing. Northwest Bulb Growers Assoc, Washington, USA.

- Gould CJ, Byther RS (1979) Diseases of tulips. Washington State University, USA.

- Krabbendam P (1966) Flower bulb cultivation, I1 De Tulp. 10th In: Uitgevers Mij NV, Tjeenk Willink WCJ, Zwolle (Eds.), The Netherlands.

- Moore WC, Brunt AA, Price D, Rees AR (1979) Diseases of bulbs. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, London, UK.

- De Hertogh AA (1983) The tulip: Botany, usage, growth and development/horticultural reviews.

- Royal general association for flower bulb culture (1976) Classified list and international register of tulip names. Hillegom, Netherlands, Europe.

- Royal General Association for flower bulb cultivation (1981) Classified list and international register of tulip names. Hillegom, Netherlands, Europe.

- Ministry of agriculture, fisheries and food (1913) Tulip forcing. Booklet B2300. Alnwick, England, UK.

- Rees AR (1972) The growth of bulbs. Academic Press, London, UK.

© 2023 Shukrullozoda Roza Shukrullo Qi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)