- Submissions

Full Text

Intervention in Obesity & Diabetes

Utilization of Diabetes-Specific Nutrition among Community-Dwelling Malnourished People with Diabetes: Results of a Quality Improvement Program

Refaat Hegazi1,2*, Katie Riley3, Sarah Kozmic3, Wendy Landow, Gretchen VanDerBosch3, Krishnan Sriram3 and Suela Sulo1

1Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, USA

2Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Egypt

3Advocate Aurora Health Formerly known as Advocate Health Care, USA

*Corresponding author: Refaat Hegazi, Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, USA

Submission:June 09, 2020;Published: June 29, 2020

ISSN 2587-0263Volume4 Issue3

Abstract

Diabetes-specific nutrition could play an important role in the overall management of diabetes. Diabetes-specific nutritional formulas (DSNF) could be beneficial for the management of people with diabetes (PWD) who are malnourished or at risk. The role of primary care physicians as drivers of DSNF recommendations was assessed via phone surveys in community-dwelling PWD at malnutrition risk participating in a home-based nutrition focused quality improvement program (QIP). Of patients surveyed, 93.2% were still using DSNF within 30-45 days of enrollment in QIP and 238 of 266 (89%) were “very-” or “somewhat-” likely to continue DSNF if they were recommended by a physician. In PWD receiving home healthcare, patient education, and professional recommendation of DSNF by physicians could reinforce utilization and better adherence. Hospitalization rates were also reduced for patients enrolled in the QIP as compared to at-risk/malnourished pre-QIP historical PWD controls; relative risk reductions were 21.7% at 30 days (12.6% vs. 16.1%, p=0.053), 28.1% at 60 days (17.9% vs. 24.9%, p=0.001), and 28.3% at 90 days (21.8% vs. 30.4%, p<0.001). Nutrition-focused QIPs and physician driven recommendations for DSNF can improve patient engagement in nutrition therapy and decrease hospitalization rates.

Keywords: Diabetes; Diabetes-specific nutrition; Oral nutritional supplements adherence; Hospitalizations

Abbreviations: PWD: People with Diabetes; QIP: Quality Improvement Program; DSNF: Diabetes-Specific Nutritional Formulas; AHC: Advocate Health Care; SNF: Skilled Nursing Facility

Introduction

Diabetes puts significant demands on the US healthcare system, both clinically and economically [1]. People with diabetes (PWD) commonly have increased risk for malnutrition, even as many with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are overweight or obese. Liu G-X et al reported that 33% of patients in a T2DM study population were at of risk of malnutrition and 21% were malnourished [2]. In another study of people with T2DM, risk or presence of malnutrition was even more prevalent, i.e., 39% and 48%, respectively [3]. Using retrospective cohort data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), beneficiaries with diabetes and malnutrition had reduced survival and increased healthcare costs compared to those with diabetes who were adequately nourished [4].

Diabetes-specific nutritional formulas (DSNF) have been shown to improve clinical and economic outcomes among PWD. These specialized nutritional formulas contain nutrients (e.g., slowly digested low glycemic index carbohydrates, mono-unsaturated fatty acids) that are shown to improve glycemic responses and induce the secretion of incretins. Nutritional care protocols have been found to improve clinical outcomes (e.g., length of stay, readmissions, costs) of at-risk/malnourished inpatients [5] and little is known about the impact of similar initiatives with community-dwelling adults receiving care in other healthcare settings

Mini Review

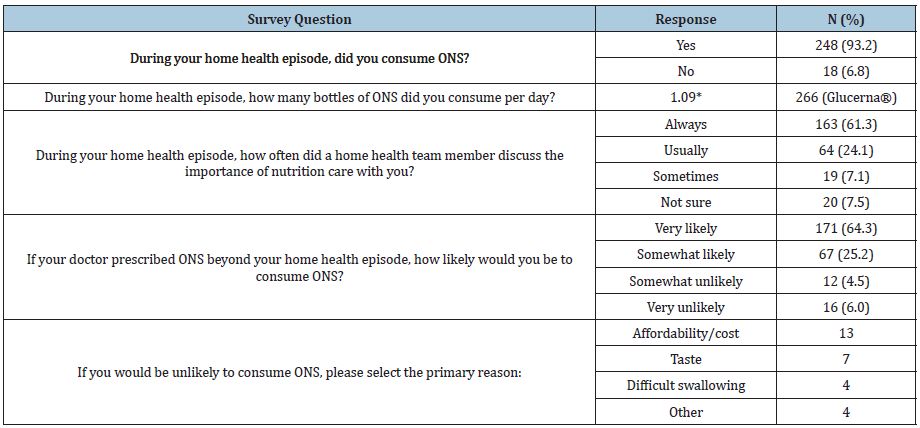

A quality improvement program (QIP) conducted at Advocate Health Care (AHC), the largest integrated healthcare delivery system in Illinois, US., in addition to patients with multiple diagnoses, it enrolled PWD who were using AHC services. Patients were eligible for the QIP if they were admitted to the home health agency (HHA) from an AHC hospital, outpatient clinic, or affiliated skilled nursing facility (SNF); and were ≥18 years of age; at risk for malnutrition upon hospital discharge and/or upon home healthcare enrollment able to consume food and beverages orally. The admitting clinicians ordered 2 bottles of DSNF for 30-days which was delivered directly to the patients’ home. Coupons were distributed to all participating QIP patients to encourage continuation of DSNF use after the study. All QIP patients were contacted for a follow-up phone survey 30 to 45 days after home healthcare began. Other patient and QIP characteristics are previously published by Riley et al. [6]. The study was approved by the AHC Institutional Review Board and was registered under ClinicalTrials.gov identifier no. NCT03011944. In this paper, we focus on patient’s experience of the use of DSNF as part of a nutrition-focused QIP, and whether use of a comprehensive, QIP could lower risk for hospitalizations over a 90-day period among the at-risk/malnourished PWD as compared to a comparable group of historical controls. Approximately 57% of QIP patients (266 of 468) responded to the survey. The vast majority (93.2%) reported that they had consumed DSNF during their home health episode. On average, 1.09 bottles of DSNF were consumed per day. In terms of nutrition education and reinforcement, most patients (85.3%, 227 of 266) reported that a member of the home healthcare team “Always” or “Usually” talked to them and 238 of 266 patients (89%) were “very-” or “somewhat-” likely to continue DSNF if they were recommended by a physician (Table 1). The QIP group participants were, on average, slightly older than the historical control group (76.1 years vs 73.3 years). More patients in the QIP group identified their race as Black or Other compared to the historical controls (43.2% vs 40.1% and 16.7% vs 9.6%, respectively).

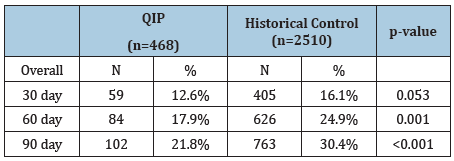

Hospitalization rates at all three measured time points were reduced for the QIP PWD as compared to the pre-QIP historical controls (Table 2). The relative risk reductions were 21.7% at 30 days (12.6% vs. 16.1%, p=0.05); 28.1% at 60 days (17.9% vs. 24.9%, p=0.001); and 28.3% at 90 days (21.8% vs. 30.4%, p<0.001).

The current study illustrated that incorporation of DSNF into standard clinical care was feasible, and this practice led not only to positive patient-reported experiences but reduced hospitalization rates as well. These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating the effectiveness of DSNF for PWD. For instance, Hamdy et al. [7] found that orally-fed, hospitalized patients with diabetes who received glycemia-targeted specialized nutrition had a 0.17 day (95% CI: 0.14-0.21) shorter length of stay than similar patients receiving standard nutrition [7]. The shorter length of stay associated with this specialized nutrition care contributed to a cost savings of $1,356 per patient. In another study from an outpatient clinic in Spain, Sanz-Paris and colleagues found that nutritional supplementation with a DSNF for one year in malnourished older people with T2DM (n=93, mean age 84.9 years) significantly reduced healthcare costs by 65.6% [3]. Over a one-year interval, there were fewer hospital admissions recorded (by 54.7%), fewer days spent in hospital (by 64.1%), and fewer emergency department visits (by 57.7%).

Table 1: Results of a phone survey conducted 30-45 days post home healthcare enrollment (N=266).

Discussion

A key barrier to counseling and treating poorly nourished patients is that most physicians are not trained in nutrition interventions [2]. Only 12% of office visits in the US are reported to include counseling about diet, and only about 1 in 5 patients with high-risk diagnoses (such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) receive nutrition counseling [8,9]. Taking the time to talk to patients about nutrition is also time-consuming. While some PWD receive in-office or follow-up counseling when type 2 diabetes is diagnosed. However, in resource-poor settings, a patient may leave the clinic with a list of new medications and little else. Numerous nutrition-focused QIP studies have shown that malnutrition risk screening along with the provision of oral nutritional supplements when risk is detected, can enhance identification of patients at risk of malnutrition, improve outcomes, and lower costs of care [5,6,10]. In fact, the reduction in 90-day hospitalization rate observed in our study can lead to potential cost savings since the cost of hospitalization for malnourished adult patients is $17,985 [11].

Table 2: Hospitalization rates of patients with diabetes.

Conclusion

The results of our study in a home healthcare population underscore the importance of nutrition-focused care beyond the hospital and into the community for PWD as well as the physicianled recommendations for DSNF to enforce patient adherence. Improvements in nutrition care lead to better patient outcomes and also could benefit healthcare systems in terms of reduced use of healthcare resources and lowered costs.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant to Advocate Health Care from Abbott.

Conflict of Interest

Ms. Riley, Ms. VanDerBosch and Dr Sriram have received consultancy fees from Abbott outside the present work. Dr. Hegazi and Dr. Sulo are employees and stockholders of Abbott.

References

- Forouhi NG, Misra A, Mohan V, Taylor R, Yancy W (2018) Dietary and nutritional approaches for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. BMJ 361: k2234.

- Liu GX, Chen Y, Yang YX, Yang K, Liang J, et al. (2017) Pilot study of the mini nutritional assessment on predicting outcomes in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17(12): 2485-2492.

- Beckman JA, Creager MA (2016) Vascular complications of diabetes. Circ Res 118(11): 1771-1785.

- Sanz Paris A, Boj Carceller D, Lardies Sanchez B, Perez Fernandez L, Cruz Jentoft AJ (2016) Health-care costs, glycemic control and nutritional status in malnourished older diabetics treated with a hypercaloric diabetes-specific enteral nutritional formula. Nutrients 8(3): 153.

- Ahmed N, Choe Y, Mustad VA, Chakraborty S, Goates S, et al. (2018) Impact of malnutrition on survival and healthcare utilization in Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes: A retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 6(1): e000471.

- Sriram K, Sulo S, VanDerBosch G, Partridge J, Feldstein J, et al. (2017) A comprehensive nutrition-focused quality improvement program reduces 30-day readmissions and length of stay in hospitalized patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 41(3): 384-391.

- Riley K, Sulo S, Dabbous F, Partridge J, Kozmic S, et al. (2019) Reducing hospitalizations and costs: A home health nutrition-focused quality improvement program. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 44(1): 58-68.

- Hamdy O, Ernst FR, Baumer D, Mustad V, Partridge J, et al. (2014) Differences in resource utilization between patients with diabetes receiving glycemia-targeted specialized nutrition vs standard nutrition formulas in U.S. hospitals. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 38(2 Suppl): 86S-91S.

- Kahan S, Manson JE (2017) Nutrition counseling in clinical practice: how clinicians can do better. JAMA 318(12): 1101-1102.

- Meehan A, Loose C, Bell J, Partridge J, Nelson J, et al. (2016) Health system quality improvement: Impact of prompt nutrition care on patient outcomes and health care costs. J Nurs Care Qual 31(3): 217-223.

- Fingar KR, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, Elixhauser A, Steiner CA, et al. (2006) All-cause readmissions following hospital stays for patients with malnutrition, 2013: Statistical Brief #218. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

© 2020 Refaat Hegazi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)