- Submissions

Full Text

Intervention in Obesity & Diabetes

Overweight and Obese Sample of Middle-Aged and Older Australian Adults: An Implementation Intervention of the Ecofit Program

Wilczynska M, Jansson AK, Lubans DR, Smith JJ, Robards SL and Plotnikoff RC*

Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, VA, USA

*Corresponding author:Ronald C Plotnikoff, Priority Research Centre in Physical Activity and Nutrition, Callaghan, Australia

Submission:January 16, 2020;Published: January 24, 2020

ISSN 2578-0263Volume3 Issue3

Abstract

Background: Ecofit is an evidence-based multi-component physical activity intervention that integrates smartphone technology, the outdoor environment and social support. In a previous efficacy trial, significant improvements were found across several clinical, fitness, and mental health outcomes among adults at risk of (or with) type 2 diabetes.

Methods: The aim of the present study is to evaluate the ecofit intervention in a ‘real-world’ setting using a scalable implementation model. Ecofit was adapted and implemented by a rural municipal council in the Upper Hunter Shire, New South Wales, Australia and evaluated using a single-group pre-post design. Inactive middle-aged and older adults (N=59) were recruited and assessed at 6- (primary time-point) and 20-weeks (follow-up).

Result: Statistically significant improvements were found in this predominately overweight and obese sample for aerobic fitness, functional mobility, upper and lower body muscular fitness, systolic blood pressure and waist circumference at 6-weeks. At 20-weeks, effects were found for aerobic fitness, functional mobility, upper and lower body muscular fitness, and systolic blood pressure.

Conclusion: Our findings support the effectiveness of the ecofit intervention delivered by municipal council staff following a brief training from the research team. This study provides valuable preliminary evidence to support of a larger implementation trial.

Keywords: Smartphone application; Physical activity; Outdoor environment; Older adults

Introduction

Participation in regular physical activity is associated with reduced risks of cardiovascular disease, overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), numerous cancers, mental, musculoskeletal, reproductive health problems and reduced falls risk in elderly [1-4]. In addition, higher levels of physical activity have been linked to enhanced social and psychological functioning, including reduced anxiety, depression and stress [5]. Despite the benefits, 50% of adults (aged 18-64) and 75% of older adults (65-years and over) in Australia do not accrue enough physical activity [6]. The present study follows on from the original ecofit efficacy trial, which is a multi-component community-based physical activity intervention that integrates smartphone technology, the outdoor environment, and social support [7,8]. This randomized controlled trial targeted adults at risk of, or diagnosed with, type 2 diabetes who were not meeting physical activity guidelines. At the 10-week primary time-point, the study found significant effects for aerobic fitness, physical activity, upper and lower body muscular fitness, functionality, waist circumference and systolic blood pressure [7]. Most of these effects were sustained at the 20-week follow-up (i.e., aerobic fitness, upper and lower body muscular fitness, functional mobility, systolic blood pressure, waist circumference and depression symptoms) [7]. Following the success of the efficacy trial, the aim of the current study was to conduct a pilot evaluation of the ecofit intervention using a scalable implementation model (i.e., municipal council delivery) among inactive middle-aged and older adults residing in an Australian rural community.

Methods

Study design

The present implementation intervention was evaluated using a pre-post experimental research design. The 20-week study was based on the ecofit efficacy trial, protocol published elsewhere [8]. The ecofit program was adapted and implemented by health officers employed by the Upper Hunter Shire Council, New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Assessments were conducted at baseline, 10-weeks and 20-weeks post-baseline. Ethics approval for this study was obtained by the University Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Newcastle (H-2014-0174).

Participants

Participants were recruited by the Upper Hunter Shire Council

using a variety of strategies (e.g., local radio stations, flyers,

newspaper advertisements and local seniors’ clubs). Inclusion

criteria included:

A. ≥45 years of age, and

B. not meeting current physical activity guidelines.

Participants were excluded if they had a medical condition that

might preclude participation in physical activity. All participants

provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Intervention components

The face-to-face sessions were adopted from the ecofit efficacy trial [8] and were composed of two parts; cognitive mentoring (30-minutes) followed by an outdoor exercise session (60-minutes). The cognitive mentoring sessions were developed to provide participants with skills and strategies to overcome barriers, increase motivation and set goals. The supervised outdoor training sessions were developed to provide participants with the confidence, skills and knowledge to perform aerobic and resistance activities using the outdoor built environment (e.g., stairs, railings, benches). Sessions were composed of six resistancebased exercises (i.e., abdominal strengthening, external rotations, knee lifts, pulls-ups, push-ups, and squats) and approximately three kilometers of moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic activity (i.e., walking or jogging). Participants were also provided with the ecofit smartphone app for the duration of the study. The app had been adapted from the ecofit efficacy trial [8] and included tailored workouts designed specifically for four locations in the Upper Hunter Shire, a rural area of NSW.

Intervention overview

The intervention consisted of two phases: Phase 1 (1-6 weeks) and Phase 2 (7-20 weeks). During Phase 1, participants attended the face-to-face session once per week. Phase 2 consisted of three parts, the first part of Phase 2 (first 4-weeks) participants received no face-to-face sessions but were encouraged to meet with other participants to continue their workouts. Participants were then provided with weekly face-to-face sessions again for a further 4-weeks (10-13-week time-point), this was followed by four weeks of no sessions (14-20-week time-point). For the duration of the project, participants had access to the purpose-built ecofit smartphone application. A training day was held at the University of Newcastle for the two Council representatives (qualified health professionals) who would conduct the assessments and deliver the intervention. The Council representatives were trained by the original ‘ecofit’ research team. This training included information on how to conduct the face-to-face training and cognitive mentioning sessions, and the protocols for undertaking participant assessments.

Outcomes

Assessments were conducted at baseline, 6-weeks (primary time-point) and at 20-weeks (follow-up). Baseline assessments were conducted prior to commencing in the ecofit implementation program. At all three time-points, participants were measured on most measures from the ecofit efficacy trial including, aerobic fitness, functional mobility, upper and lower body muscular fitness, blood pressure, and waist circumference. (See original protocol for information on specific measures [8]). A process evaluation survey was provided to all participants who attended their final followup assessment. All assessments were administered by the trained Upper Hunter Shire Council representatives. Upon completion of assessments, data log sheets were returned to the researchers at the University of Newcastle for analysis.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis of the study outcomes was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 22.0. Two paired-sample t-tests were conducted to compare health-related outcomes between baseline and 6-weeks, and between baseline and 20-weeks. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ demographics.

Result

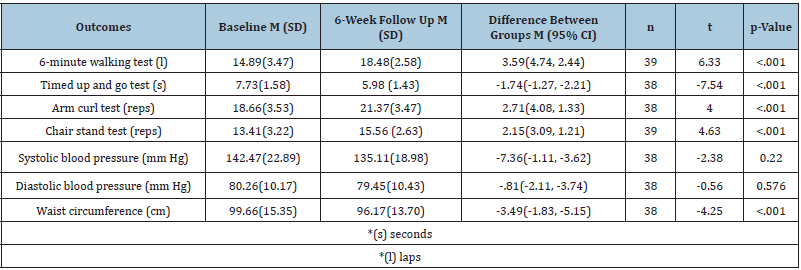

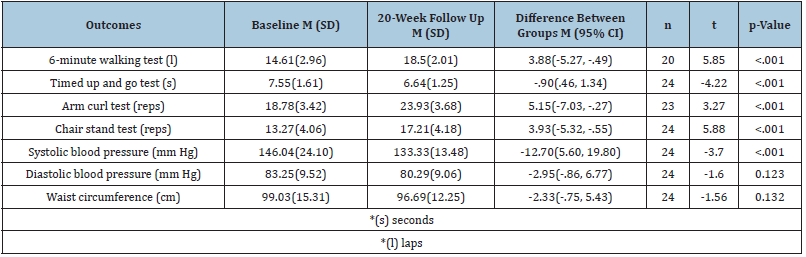

The demographic characteristics of the sample consisted of the following: M (age)=62.3 years (SD=11.58), 95% females, M (Body Mass Index (BMI))=30.68 (SD=6.3) with 47% and 38% classified as obese and overweight respectively [9]. At the 6-week time-point, statistically significant (p<0.05) improvements were observed for aerobic fitness, functional mobility, upper and lower body muscular fitness, systolic blood pressure and waist circumference (Table 1). There were no statistically significant (p>0.05) improvements for systolic or diastolic blood pressure. At the 20-week follow-up, statistically significant (p<0.05) improvements were observed for aerobic fitness, functional mobility, upper and lower body muscular fitness, and systolic blood pressure (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences (p>0.05) for diastolic blood pressure or waist circumference.

Process evaluation

In total, 24 participants (41.3%) attended their 20-week follow-up assessments. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Overall, participants were satisfied with the program (M=4.26, SD=0.92) and found that it provided them with useful information and skills on how to be physically active (M=4.39, SD=0.66).

Table 1:Results at the 6-week primary time-point.

Table 2:Results at the 20-week time-point.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine the conduct a

small-scale pilot evaluation of the ecofit intervention using in

a rural setting and using a scalable implementation model (i.e.,

municipal council staff delivery). Similar to the efficacy trial [7], we

found significant improvements in almost all outcomes (i.e., aerobic

fitness, functional mobility, upper and lower body muscular fitness,

systolic blood pressure and waist circumference) at the 6-week

time-point and most were sustained (i.e., aerobic fitness, functional

mobility, upper and lower body muscular fitness, and systolic blood

pressure) at the 20-week follow-up. Meeting both the aerobic

and the muscle strengthening physical activity guidelines among

this population has been associated with many physiological,

psychological and clinical benefits [1,2]. Thus, the results from this

study are promising given the prevalence of meeting the physical

activity guidelines are very low among this population age group

[6]. Based on the process evaluation, people were satisfied with

the program, however many participants reported not using the

app due to poor internet connection. Indeed, using web-based

technology may prove problematic in rural areas due to poor

internet services, and/or poor technological literacy among older

adults. This is an important consideration for future studies that

plan to carry out web-based interventions in rural areas, although

our findings also suggest the face-to-face component may have

been sufficient to improve outcomes among this group (and indeed

may be preferable). While many physical activity interventions

have proven effective in controlled research settings, few studies

to date have been conducted in ‘real world’ environments [10].

Indeed, successful translation and maintenance of efficacious

physical activity interventions is complex and challenging, and

few successful examples appear in the published literature. For

intervention strategies to shift populations to be more active, joint

efforts between researchers, government agencies and the general

community is essential for the ‘scale-up’ of efficacious interventions

[10].

Thus, local Councils are in ideal positions to assist with physical

activity promotion as one of their main objectives are to promote

health and well-being amongst residents through the provision of

facilities [11]. The main study strength is the assessment of how

an efficacious program can be implemented in a real-world context

with limited involvement from the researchers. Another strength

is the design of the program. The ecofit program only requires

simple infrastructure (i.e., railings, stairs, benches) and thus can be

adapted to most outdoor locations. Limitations of the study include

a non-randomized controlled trial design and the loss of sample

at the 20-week follow-up. Another limitation is the study did not

assess plasma glucose, and low and high-density lipoproteins in this

‘at risk’ population. These biomarkers are of significant importance to determine the success of the ecofit implementation program on

cardiovascular disease. This research, however, will hopefully guide

researchers and practitioners in the design and implementation of

practical programs which target the growing overweight and obese

population at risk of and/or living with type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Nicolle Western and Ella Brotherton (Upper Hunter Shire Council) who helped with this study.

References

- Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS (2006) Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ 174(6): 801-809.

- Sousa N, Mendes R, Silva A, Oliveira J (2017) Combined exercise is more effective than aerobic exercise in the improvement of fall risk factors: A randomized controlled trial in community-dwelling older men. Clinical Rehabilitation 31(4): 478-486.

- Zamboni M, Mazzali G, Fantin F, Rossi A, Di Francesco V (2008) Sarcopenic obesity: A new category of obesity in the elderly. Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases 18(5): 388-395.

- (2017) Impact of physical inactivity as a risk factor for chronic conditions Australian burden of disease study. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, p. 65.

- Spruijt Metz D, Nguyen Michel ST, Michael I Goran, Chih Ping Chou (2008) Reducing sedentary behavior in minority girls via a theory-based, tailored classroom media intervention. International journal of pediatric obesity: IJPO: An official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 3(4): 240-248.

- (2018) Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australia’s health, Canberra, Australia.

- Plotnikoff RC, Wilczynska M, Cohen KE, Smith JJ, Lubans DR (2017) Integrating smartphone technology, social support and the outdoor physical environment to improve fitness among adults at risk of, or diagnosed with, type 2 diabetes: Findings from the 'eCoFit' randomized controlled trial. Prev Med 105: 404-411.

- Wilczynska M, Lubans DR, Cohen KE, Smith JJ, Robards SL, et al. (2016) Rationale and study protocol for the 'eCoFit' randomized controlled trial: Integrating smartphone technology, social support and the outdoor physical environment to improve health-related fitness among adults at risk of, or diagnosed with, Type 2 Diabetes. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 49: 116-125.

- Bryan CL, Solmon MA, Zanovec MT, Tuuri G (2011) Body mass index and skinfold thickness measurements as body composition screening tools in Caucasian and African American Youth. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport 82(2): 345-349.

- Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, et al. (2016) Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: Stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet 388(10051): 1337-1348.

- Steele R, Caperchione C (2005) The role of local government in physical activity: Employee perceptions. Health Promotion Practice 6(2): 214-218.

© 2020 Ronald C Plotnikoff. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)