- Submissions

Full Text

Investigations in Gynecology Research & Womens Health

Physical and Gynecological Outcomes among South African Women Survivors of Rape

Teri D Davis1*, Tamra Burns Loeb2, Dorothy Chin2, Nombulelo V Sepeng3, Mashudu Davhana Maselesele4, Jenny Park1, Muyu Zhang2, Michele Cooley Strickland2 and Gail E Wyatt2

1Department of Clinical Psychology, USA

2Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, USA

3Department of Nursing, South Africa

4Rectorate, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa

*Corresponding author: Teri D Davis, Department of Clinical Psychology, USA

Submission: November 18, 2020;Published: December 22, 2020

ISSN: 2577-2015 Volume3 Issue5

Abstract

Introduction: South Africa has one of the highest rates of sexual violence against females in the world [1,2]. Residual outcomes among rape survivors in South Africa are complex, and include symptoms of depression, and post-traumatic stress (PTSS) [3,4] as well as physical and gynecological problems [5,6]. While South African rape survivors report physical and mental health symptoms [7]. We know little about the internal (i.e. self-management) and external (i.e. support from others) coping strategies that they use over time.

Objectives: This study conducted secondary analyses of South African female rape survivors who reported experiences of rape within six months of being interviewed and compared their physical and mental health, coping strategies, rape myths and social undermining of friends and families one year later. The goal is to foster a discussion of post-rape outcomes that may be utilized to develop recovery interventions for South African women rape survivors who may seek gynecological care and related health care services.

Method: Participants self-reported demographic data, physical health symptoms including gynecological symptoms (i.e. pain during sex), post-traumatic stress and depression, coping strategies, rape myths, and social undermining at baseline and 12-month follow up.

Results: Similar to the parent study (n=248), the present sample of women (n=77) were 18-50, on average 27 years of age, single (88%), unemployed (75%) and low-income with few resources, but were more educated. T tests and chi-square tests were performed to compare physical health symptoms, symptoms of post-traumatic stress and depression, coping styles, rape myths and social undermining at baseline and 12-month follow-up. High levels of post-traumatic stress and moderate levels of depression, overall physical symptoms, and specific gynecological complaints were maintained over time. Women increased their use of several personal coping strategies, and a decrease in emotional support. They reported an increase in social undermining from family and friends and endorsed more rape myths over the study period.

Conclusion: Gynecologists and other health providers treating South African women need to assess histories of nonconsensual sexual experiences (rape) and mental health issues when patients present with physical symptoms that may have been trauma-induced and refer them for more care. Although their use of coping strategies increased, women’s mental and physical health symptoms persisted over time. Rape survivors may have required more targeted support to cope with mental and physical health symptoms. Gynecological care and behavioral interventions tailored to address the sociocultural context in which these experiences occur are needed to mitigate the negative-and persistent-health consequences of rape and to increase their gynecological health.

Keywords: Rape; South Africa; Women; Physical symptoms; Gynecological symptoms; Post- traumatic stress symptoms

Background

South Africa has one of the highest rates of sexual violence in the world [1], with females comprising over 90% of the reported rape victims [2]. Residual outcomes among rape survivors in South Africa are complex, including clinical presentations of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3,4] as well as a range of somatic symptoms and/or physical complaints (e.g., somatic, neurological, gastrointestinal symptoms, musculoskeletal issues, cardiopulmonary symptoms, to gynecological concerns-painful intercourse, pelvic pain, and abnormal menstruation) [5-8]. Given of presentation of comorbid physical and mental symptoms, survivors of rape may initially present in primary care settings with diffuse pain, placing their treatment firmly with primary care and/or women’s specialty clinicians [8-11]. More care, however, may be needed.

The cultural and historical context of rape in South Africa is important to consider when conceptualizing post-rape health outcomes. During the apartheid era, rape was used “as a weapon” of oppression of South Africa’s Black population which reinforced it as an unavoidable circumstance of life for many South African women [12]. Other factors affecting the societal context and attitudes toward rape include unsupportive social environments, stigma, victim-blaming, self-blame in victimized individuals [13,14], and gender inequalities which pervade society [15]. Since the end of apartheid, significant legal and political advances have been made to preserve the rights of South African women. However, the lived experiences of women in South Africa are not necessarily compatible with their realities as rape survivors [16-18]. Thus, Womersley & Maw [19] note that the social-cultural context for which recovery takes place may have a negative impact on the recovery of rape survivors, which may compromise coping resources. Social responses to the violence also influence the mental health functioning of the victim [20]. It is likely that women report physical symptoms in primary health and women’s health clinic settings and the undisclosed mental health sequelae may exacerbate the long-term effects of rape, particularly in limited-resource settings such as the North West and Limpopo provinces of South Africa.

The discussion of the sociocultural contexts along with the wide range of residual post-rape symptomatology and recovery efforts, is not well understood. The present study of 77 South African women utilizes secondary analyses of 248 rape survivors from two rural South African clinics who were interviewed within 6 months of their rape experiences. Changes in their initial reports are compared on symptoms of physical, gynecological and mental health complaints, coping strategies, and thoughts about rape among South African women one year later. The goal of this work is to better inform health providers such as gynecologists and develop behavioral interventions to minimize lasting adverse physical, gynecological and mental health outcomes for South African women rape survivors.

Methods

Participants

A total of 77 women, 18 to 50 years old, who reported having been raped within the past six months were eligible participants and were recruited from one of two rural rape care clinics in the South African provinces of North West (58.4%, n=122) and Limpopo (41.6%, n=87) by lay counselors in the clinics.

Procedure

The present investigation is a secondary analysis of a larger longitudinal study (n=248) named the Fulufhelo (Hope) project aimed to evaluate South African female rape survivors who reported experiences of rape within six months of being interviewed. Women were recruited by counselors working at Thuthuzela Care Centers to receive post-rape test results (i.e., pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, HIV) during a follow-up appointment. All counselors had a high school education and completed at least six weeks of training in basic counseling techniques for individuals reporting traumatic life experiences. The consent forms were read, and study implications explained to potential participants using one of two South African languages (i.e., Setswana, TshiVenda). Each participant was informed of their right to refuse or terminate participation in the study before data collection. Participants were provided with $10.00 meal vouchers as compensation for their time (for greater detail [21]).

Per the original study, there was significant participant dropout of women with less education, which impacted the present study sample (n=77). It is possible that these women may have moved away from the area in search of employment, although more study is needed to determine the reasons for dropout [21]. This study conducted secondary analyses and compared their physical and mental health, coping strategies, rape myths and social undermining of friends and families one year later.

Measures

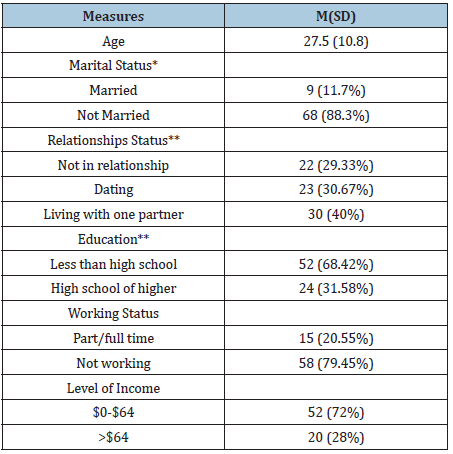

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Participants Recruited from South African Health Care Centers (n=77).

Demographic data. Participants provided basic demographic data (e.g., age, marital/relationship status, level of education, working status, income) (Table 1). More information about the measures used can be found in Wyatt et al. [21]. The Patient Health Questionnaire Physical Symptoms (PHQ-15). The PHQ-15 is a 15- item self-report questionnaire that assesses several domains of somatic symptoms [22]. Nine items were selected that represent common somatic symptoms reported after rape (e.g., stomach pains; constipation; menstrual cramps and/or pelvic pain; headaches; trouble sleeping). Each item was scored using a 3-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating the absence of the symptoms and 2 and 3 indicating the severity of symptoms. The coefficient alpha for the 9 items in this sample was 0.76, suggesting acceptable reliability.

Post-traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS). Post-traumatic stress symptoms were measured using the 17-item PDS [23,24]. The PDS was developed based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria and includes questions regarding avoidance/numbness, physiological arousal, and re-experiencing/intrusive thoughts (e.g. “Did you relive the traumatic event, acting or feeling as if it were happening again?”). Participants were asked to rate how often each symptom had bothered them in the past month on a 4-point Likert scale from “Not at all” to “Almost always”. The coefficient alpha for this sample was 0.92, suggesting high reliability of the PDS.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). This 21-item scale is a widely used self-report measure of depressive symptoms [25] including sadness, pessimism, insomnia, and irritability. Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale indicating the severity of symptoms; 0 representing an absence of depressive symptoms and 3 representing severe depressive symptoms. The coefficient alpha was 0.93 in this sample, suggesting high reliability of the BDI- II. Brief COPE Inventory. This inventory consists of 28 items assessing the use of 14 different coping strategies utilized in response to stress. In this study, four 2-item subscales (positive reframing, use of emotional support, humor, and religion) and one 6-item subscale (use of active coping) were examined. The reliable sum scores were previously calculated for this scale for use of emotional support (α=.79), religion (α=.74), and active coping (α=.83) [21].

Rape Myths. The South African adaptation of the Rape Myth Acceptance Scale [26,27] was used to measure degrees of acceptance of various rape myths (e.g., “Many rapes happen because women lead men on”). The scale is a 6-item self-reported measure utilizing a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 “Disagree” to 4 “Agree"). The reliable sum score was calculated (r=.81) [21]. Social Undermining. Women completed a three-item questionnaire to identify whether an important person in their life had engaged in criticism or caused their life to become more difficult following the rape. The questions were rated on a 3-point Likert scale from “Not at all or a little” to “Quite a lot”. Using Cronbach’s alpha, a reliable composite social undermining score was calculated (α=.90) [28].

Result

Similar to the parent study (n=248), the present sample of women (n=77) were 18-50, on average 27 years of age, single (88%), unemployed (75%) and low-income with few resources, but were more educated. Descriptive statistics were completed for the full study sample at baseline, which included 77 participants who had completed study measurements at both time points. Overall, women were on average 27 years of age, single (88%), less educated (68%), unemployed (75%), and 68% were earning an income of $60.00 or less per month. About one in three (30%) of the women were dating and 39% of them were living with one partner when they reported having been raped (Table 1).

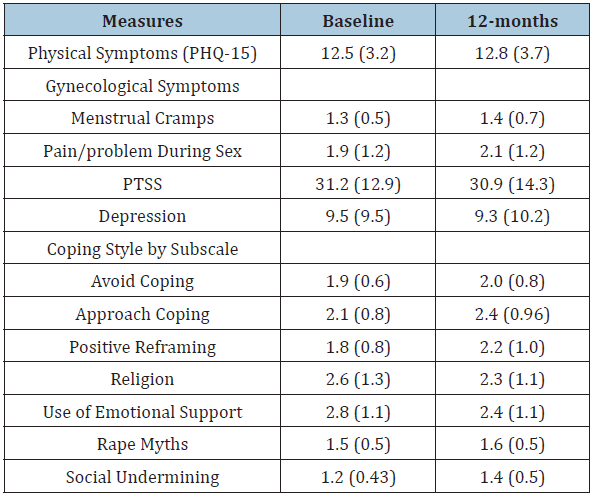

As noted in Table 2, t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables were conducted to compare variables between baseline and 12-month follow-up. Physical health symptoms, including gynecological symptoms, PTSS, depression, coping styles, rape myths, and social undermining at baseline and 12-month follow-up were performed on 77 participants who had completed study measurements at both time points. Specifically, moderate levels of physical symptoms as well as gynecological symptoms (e.g., menstrual cramps, pain or problems during sex) were found at both baseline and 12-month follow-up. No significant changes were found over time. In terms of mental health, PDS had a mean of 31.2 at baseline and 30.9 at 12-months, indicating a high level of PTSS that remained as high one year later. The mean score for the BDI-II was 9.5 at baseline and 9.3 at 12-month follow-up, indicating that depression symptoms were consistently moderate at both time points [29-32].

Table 2: T-test of study variables at baseline and 12-month followup (n=77).

Comparisons in coping with baseline and 12-month follow-up were conducted using t- tests (Table 2). Significant differences were found with respect to active coping (t=-2.52, p=0.014), positive reframing (t=-3.36, p=0.0012), and humor (t=-3.32, p=0.0014) in the positive direction, indicating that respondents were more likely to use these coping strategies over time. Religion (t=2.06, p=0.0427) and use of emotional support (t=2.32, p=0.0232) significantly decreased from baseline to 12-months. Two indicators of social context were found to differ between baseline and 12-month follow-up [33-35]. Particularly, social undermining increased significantly (t=2.32, p=0.0232), as did respondents’ endorsements of rape myths in their culture (t=-2.43, p=0.0175) [36-38].

Discussion

This study describes physical health outcomes including gynecological symptoms, mental health outcomes, coping strategies, and social context changes over 12 months among South African women who reported experiences of rape within six months of being interviewed in two rural South African province health care clinics. Demographically, women in this sample were mostly single, impoverished, and had little education. Those with the least education were more likely to drop out of the study after the initial interview. Women reported high levels of post- traumatic stress symptoms and moderate levels of depression symptoms that were sustained one year later. While an abundance of research has documented the negative mental health sequelae of rape among women, these findings highlight the importance of identifying what symptoms change or are sustained over time.

South African women in this sample increasingly employed efforts to cope on their own, in the context of the loss of support from others such as diminished emotional support (e.g., “I’ve been getting emotional support from others”), social undermining, and cultural rape myths that blame the survivor for the experience of rape. Thus, the decrease of support from others and continuance of mental health symptoms, and more internalized coping styles were correlated. Information about a wide range of post-rape health outcomes is needed to help women to be better informed about what physical, including gynecological symptoms, mental health symptoms as well as the potential course of recovery to expect that may be related to post rape experiences. Clinicians and researchers may utilize these findings to inform interventions that focus on the development of coping strategies that may be employed to address the physical and mental health symptoms that other survivors may report. It may be important to note that if families and friends may not be supportive of rape survivors after the initial event over time, it will be critical to identify how survivors develop coping strategies from other sources, if they do.

Women in this sample self-reported physical symptoms, including moderate levels of gynecological symptoms of menstrual cramps, and pain or problems during sex that were also sustained over time. This finding call attention to the need for women’s health providers to assess for nonconsensual sexual experiences and screen for mental health issues when patients present with gynecological symptoms. Notably, these findings suggest that the rape survivors’ mental and physical health symptoms persisted over time, despite significant increases in women’s coping strategies. Women described an active approach to coping with the trauma and also reported positive reframing their use of these coping strategies increased over the one-year follow-up period.

The present sample were seen in rape care clinics in their local rural South African provinces where fewer resources might have been available to them. More research is needed to determine if women in rural areas with limited resources adjust to rape experiences in the long term better than women from urban areas with more resources. However, there is no questions that these women could have benefitted from counseling about the effects of rape on their bodies and their psychological well-being at the time of and following a rape event. Without interventions tailored to discussing the type of support that is best for rape survivors and the need to continue this support over time, women might experience more of a burden of negative mental and physical health long after rape occurs. Interventions should be designed and tailored to target single South African women rape survivors under the age of 30 with a range of educational levels and resources as an active strategy to boost resilience and to minimize lasting negative physical and mental health outcomes.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by grants from Fogerty International, NIH TW007964, 5P30AI028697, and MH073453. We are indebted to the women who agreed to share their experiences.

References

- Moyo NS, Khonje E, Brobbey MK (2017) Violence against women in South Africa: A country in crisis. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation.

- https://static.pmg.org.za/SAPS_Annual_Report_20182019.pdf

- Nöthling J, Lammers K, Martin L, Seedat S (2015) Traumatic dissociation as a predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder in South African female rape survivors. Medicine 94(16): e744.

- Sepeng NV, Makhado L (2018) Correlates of post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis among rape survivors: Results and implications of a South African study. Journal of Psychology in Africa 28(6): 468-471.

- Greene T, Neria Y, Gross R (2016) Prevalence, detection and correlates of PTSD in the primary care setting: A systematic review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 23(2): 160-180.

- Kugler BB, Bloom M, Kaercher LB, Truax TV, Storch EA (2012) Somatic symptoms in traumatized children and adolescents. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 43(5): 661-673.

- Campbell R, Ahrens CE, Sefl T, Wasco SM, Barnes HE (2001) Social reactions to rape victims: Healing and hurtful effects on psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence Vict 16(3): 287-302.

- Campbell R, Seft T, Ahrens CE (2003) The physical health consequences of rape: Assessing survivors' somatic symptoms in a racially diverse population. Women's Studies Quarterly 31(1): 90-104.

- Carey PD, Stein DJ, Dirwayi NZ, Seedat S (2003) Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban Xhosa primary care population: Prevalence, comorbidity, and service use patterns. J Nerv Ment Dis 191(4): 230-236.

- Cowlin AM (2015) Does the doctor think I’m Crazy?”: Stories of low-income Cape Town women receiving a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder and their subsequent referral to psychological services. Stellenbosch University Library and Information Service.

- Larsen ML, Hilden M, Skovlund CW, Lidegaard Ø (2016) Somatic health of 2500 women examined at a sexual assault center over 10 years. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica 95(8): 872-878.

- Wood K (2005) Contextualizing group rape in post‐apartheid South Cult Health Sex 7(4): 303-317.

- Hunter JA, Figueredo AJ, Malamuth NM, Becker JV (2004) Developmental pathways in youth sexual aggression and delinquency: Risk factors and mediators. Journal of Family Violence 19(4): 233-242.

- Milesi P, Philipp S, Bohner G, Jesús LM (2020) The interplay of modern myths about sexual aggression and moral foundations in the blaming of rape victims. European Journal of Social Psychology 50(1): 111-123.

- Jewkes R, Abrahams N (2002) The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: An overview. Soc Sci Med 55(7): 1231-1244.

- Brown R (2012) Corrective rape in South Africa: A continuing plight despite an international human rights response. Annual Survey of International and Comparative Law 18(1).

- Buiten D, Naidoo K (2016) Framing the problem of rape in South Africa: Gender, race, class and state histories. Current Sociology 64(4): 535-550.

- Gqola PD (2007) How the ‘cult of femininity’ and violent masculinities support endemic gender-based violence in contemporary South Africa. African Identities 5(1): 111-124.

- Womersley G, Maw A (2009) Contextualising the experiences of South African women in the immediate aftermath of rape. Psychology in Society 38: 40-60.

- Kalra G, Bhugra D (2013) Sexual violence against women: Understanding cross-cultural intersections. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 55(3): 244-249.

- Wyatt GE, Maselesele MD, Zhang M, Wong LH, Nicholson F, et al. (2017) A longitudinal study of the aftermath of rape among rural South African women. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy 9(3): 309-316.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2002) The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine 64(2): 258-266.

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K (1997) The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychological Assessment 9(4): 445-451.

- Foa EB (1995) Posttraumatic stress diagnostic scale. National Computer Systems.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF (1996) Comparison of beck depression inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess 67(3): 588-597.

- Burt MR (1980) Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38(2): 217-230.

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, Toefy Y, Cain D, et al. (2005) Development of a brief scale to measure AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior 9(2): 135-143.

- Sarason IG, Levine HM, Basham RB, Sarason BR (1981) Assessing social support: The social support questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44(1): 127-139.

- Campbell R, Greeson MR, Bybee D, Raja S (2008) The cooccurrence of childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and sexual harassment: A mediational model of posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 76(2): 194-207.

- Carver CS (1997) You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief cope. Int J Behav Med 4(1): 92-100.

- Choudhary E, Smith M, Bossarte RM (2012) Depression, anxiety, and symptom profiles among female and male victims of sexual violence. American Journal of Men’s Health 6: 28-36.

- Geldenhuys K (2015) Barriers in reporting rape. Servamus Community-Based Safety and Security Magazine 108(8): 14-17.

- Nicol I (2003) South Africa begins getting tough on rape. Women’s eNews.

- Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Dunkle K, Morrell R (2015) Relationship between single and multiple perpetrator rape perpetration in South Africa: A comparison of risk factors in a population-based sample. BMC Public Health 15(1): 1-10.

- Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB (2002) The world report on violence and health. Lancet 360(9339): 1083-1088.

- Larsen SE, Fleming CJE, Resick PA (2019) Residual symptoms following empirically supported treatment for PTSD. Psychol Trauma 11(2): 207-215.

- https://www.saps.gov.za/services/april_to_march_2019_20_presentation.pdf

- World Health Organization (2013) Violence against women: a global health problem of epidemic proportions. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

© 2020 Teri D Davis. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)