- Submissions

Full Text

Investigations in Gynecology Research & Womens Health

Prevalence of Bacterial Vaginosis in Preterm and Term Labour-An Observational Study

Kavya K* and Aruna M

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, JJM Medical College, Davangere, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Kavya K, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, JJM Medical College, Davangere, Karnataka, India. E-mail id -dr.kavya52@gmail.com

Submission: July 22, 2019;Published: August 07, 2019

ISSN: 2577-2015 Volume3 Issue2

Abstract

Background: Bacterial vaginosis is a clinical condition caused by replacement of the normal hydrogen peroxide producing Lactobacillus sp. in the vagina with high concentrations of characteristic sets of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Bacterial vaginosis is believed to be a risk factor for preterm delivery. Bacterial vaginosis is reported in 10 - 41% of women with an evidence of maternal and fetal morbidity. Studies have shown that spontaneous abortion, preterm labour (PTL), premature birth, preterm premature rupture of membranes, amniotic fluid infection, postpartum endometritis are increased because of infection with bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy.

Objectives: To study the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in women presenting with preterm labour and term labour, to analyze the causal relationship between BV and PTL and to analyze the maternal and fetal complications associated with bacterial vaginosis.

Materials and methods: An observational study involving 100 patients with preterm and term labour (50 patients in each group) was conducted at JJM Medical College, Davangere. Bacterial vaginosis was determined to be present or absent on the basis of Amsel’s criteria. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to demonstrate the difference between both groups with respect to various categorical data. Independent ‘t’ test was used to compare the mean maternal age and mean gestational age at admission in both the groups.

Results: The proportion of patients who fulfilled Amsel’s criteria for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis was significantly more in preterm labour group as compared to term labour group, and the difference was highly significant statistically. In preterm labour group a greater number of neonates born to women who had bacterial vaginosis had low birth weight as well as neonatal complications as compared to those born to women without bacterial vaginosis. Maternal postpartum complications observed were also more in women with bacterial vaginosis as compared to women without bacterial vaginosis in preterm labour group.

Conclusion: Bacterial vaginosis is major risk factor for preterm labour. Therefore, the testing for bacterial vaginosis and its prompt treatment may reduce the risk of preterm labour. This will also go a long way in the prevention of neonatal complications due to prematurity.

Keywords: Bacterial vaginosis; Preterm labour; Term labour

Introduction

Preterm labour (PTL) and delivery are among the most challenging obstetric complications encountered. PTL is the important single determinant of adverse infant outcome in terms of both survival and quality of life. It complicates about 5-10% of all pregnancies and in about 30% it is due to deliberate medical intervention and in the remainder due to spontaneous PTL. PTL is associated with 75% of all perinatal deaths [1]. In most cases, the exact cause of PTL is not diagnosed and the etiology is likely to be multifactorial. Various measures have been tried to predict PTL, e.g. risk scoring, biophysical, and biochemical markers, but not proved useful and are associated with overall poor predictive value [2].

Identification of nulliparous patient at risk for PTL remains problematic because the single most important predictor of PTL is a previous PTL. The last century has been marked by a persistent rise in rate of PTL representing the failure of modern obstetrics to understand the complexity of phenomena and to develop effective PTL preventive interventions. Risk factors fail to predict as many as 70% of PTL. Of the many approaches to PTL prevention that have been thoroughly investigated, no single intervention has been thoroughly investigated or thoroughly studied as much as transvaginal scan (TVS) and vaginal smear examination in screening for PTL [3].

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) affects 6-32% of pregnant women. It is characterized by an imbalance in the vaginal microflora which may be symptomless, or it may be accompanied by increased vaginal discharge, which may be foul smelling with a fishy odor. In women with BV, there are usually no clinical signs of infection in the vaginal mucosa. It is a risk factor for preterm delivery and is associated with peripartum complications such as preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), chorioamnionitis, and postpartum endometritis [4]. BV is one of the most common genital infections in pregnancy which is associated with two to threefold increase in infection of amniotic fluid, infection of the chorion and amnion, and histological chorioamnionitis [5].

As per the study conducted by Saifon et al. [4] the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in preterm labour group was higher than in the term labour group [4]. Intrauterine infection may occur early in pregnancy or even before pregnancy and remain asymptomatic and undetected for months until preterm labour or premature rupture of membranes (PROM) occurs. Preterm labour precedes almost half of preterm births. Preterm birth occurs in approximately 12% of pregnancies and is one of the leading causes of neonatal mortality worldwide. Studies conducted by Gregor J et al. [5] showed that combination of vaginal pH with vaginal sialidase and prolinase activities can predict low birth weight and preterm birth [6,7].

Recent interventional studies by Ugwumadu et al. [8] showed that screening for BV early in pregnancy and subsequent treatment with metronidazole or clindamycin in low-risk women may reduce the risk of spontaneous delivery before 37 weeks and the associated maternal and fetal complications [8]. As per the studies conducted by Eschenbach et al. [9] presence of clue cells is the single most reliable predictor of BV. In women with BV, at least 20 percent of the epithelial cells on wet mount should be clue cells. Using gram stain as the gold standard, the sensitivity of Amsel’s criteria for diagnosis of BV is over 90% and specificity over 77% [9-11].

In India not many studies have been done to estimate the association of BV with peripartum and perinatal complications, hence this study was taken up to know the prevalence of BV in term and preterm patients.

Objective

Primary objective

a) To study the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in women presenting with preterm labour and term labour.

b) To analyze the causal relationship between bacterial vaginosis and preterm labour.

Secondary objective

a) To analyze maternal and fetal complications associated with bacterial vaginosis.

Material and Methods

• Health care setup-Tertiary care hospital

• Setting- JJM Medical College, Davangere, Karnataka.

• Duration of the study- 2016 to 2018 (2 years)

• Type of the study- Observational study

• Sample size-100

• Level of evidence-Level V

After getting IEC clearance from the institute and informed written consent from the patients enrolled in our study, they were subjected for thorough examination. A case record form was used to record maternal age, obstetric history, past medical/ surgical history, sexual history, socioeconomic status, history of drug and alcohol abuse, gestational age at admission, physical examination data, gestational age at delivery, the route of delivery, and the newborn birth weight and conditions. The gestational age was calculated from the first day of the last menstrual period and earliest available ultrasound scan. If the estimated gestational age by menstrual and ultrasound estimation showed a difference of more than seven days, the ultrasound estimation was used.

Pelvic examination was performed. Using a sterile vaginal speculum vaginal swab was collected from lower one-third of the vaginal wall. The vaginal swab was subjected to Gram staining. Vaginal discharge was taken for wet mount for detection of clue cells and KOH test (Whiff test). The pH of vaginal discharge was tested using litmus paper. If there was no obvious discharge vaginal scraping was taken for the above test. Bacterial vaginosis was diagnosed based on Amsel’s criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Preterm labour (Group 1)

a) Gestational age less than 37 weeks.

b) Regular uterine contractions (four or more in 20 minutes or eight or more in 60 minutes), each lasting more than 40 seconds.

c) Cervical dilatation equal to or greater than 1 cm but less than 4 cm and effacement equal to or greater than 80%.

d) Intact fetal membranes.

Term labour (Group 2)

a) Gestational age >37 completed weeks

b) Spontaneous in onset

c) Regular uterine contractions (four or more in 20 minutes or eight or more in 60 minutes), each lasting for more than 40 seconds

d) Cervical dilatation equal to or greater than 1 cm but less than 4cm

e) Intact fetal membranes

Exclusion criteria

a. Rh isoimmunization.

b. Use of antibiotics in the preceding two weeks.

c. Multiple gestation.

d. Cervical cerclage.

e. Structural uterine abnormalities.

f. Established fetal anomalies

g. Prior use of tocolytic agents during the current pregnancy.

h. Pregnancies complicated with medical disorders like hypertension, diabetes, chronic renal disorders, thyroid disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, severe cardiac disorders etc.

i. Current use of corticosteroids.

j. Patients who presented with mucous bloody show.

k. Patients who were not willing to give consent.

Primary outcome measures

Bacterial vaginosis was diagnosed if 3 or more of the following criteria were present (Amsel’s criteria):

a) Elevated vaginal pH>4.5

b) Thin, homogeneous grey-white discharge

c) Amine odor upon the addition of 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) to vaginal fluid on a glass slide (Whiff test)

d) The presence of ‘clue cells’ (vaginal epithelial cells with indistinct borders due to attached bacteria) on microscopic examination of vaginal fluid.

A score of 0 to 10 was assigned depending on the Gram staining findings, on the basis of the relative proportions of easily distinguished bacterial morphologic types (i.e. large gram-positive rods, small gram-negative or variable rods, and curved rods). A score of 0 was assigned to the most lactobacillus-predominant vaginal flora, and a score of 10 was assigned to a flora in which lactobacilli were largely replaced by Gardnerella, Bacteroides, and Mobiluncus (Nugent’s scoring) [6].

Secondary outcome measures

a) Organisms grown on culture of high vaginal swab in both the groups.

b) CRP in both the groups.

c) Birth weight in both the groups.

d) Number of NICU admissions and neonatal complications in both the groups.

e) Post-partum complications in both the groups.

Result

SPSS version 20.0 was used to perform the statistical operations. The categorical data has been represented as frequency and percentages. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to find out the significance of differences in the various categorical data in both the groups. Independent t-test was performed to compare the mean maternal age and mean gestational age at admission in both the groups.

Figure 1:Nature of discharge among both the groups.

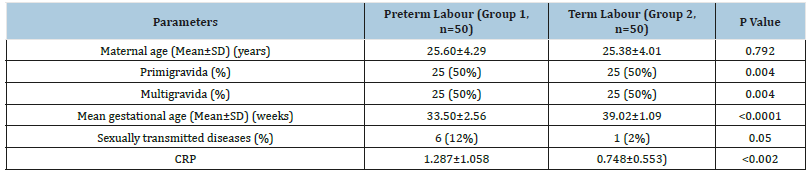

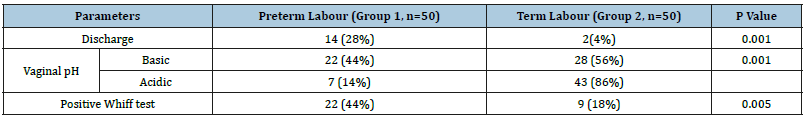

The proportion of patients who had history of sexually transmitted diseases in the past was significantly more in preterm labour group as compared to term labour group with a p value of 0.050 and the mean CRP value recorded in preterm labour group was significantly more than in term labour group, and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.002) as shown in Table 1.The pre-term labour group had more number of patients with the different grades of discharge as compared to term labour group; the difference was statistically significant with p value of 0.005 as shown in Figure 1.The proportion of patients with discharge, vaginal pH and positive Whiff test suggestive of bacterial vaginosis was significantly more in preterm labour group as compared to term labour group with significant statistical difference as mentioned in Table 2.

Table 1:Demographical statistics.

Table 2:Clinical parameters.

Out of 50 patients in both the groups, a total of 15(30%) and 2(4%) patients of preterm and term labour confirmed the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. The proportion of patients who were diagnosed to have bacterial vaginosis according to Amsel’s criteria was significantly more in preterm labour group than in term labour group, with a p value of 0.001.

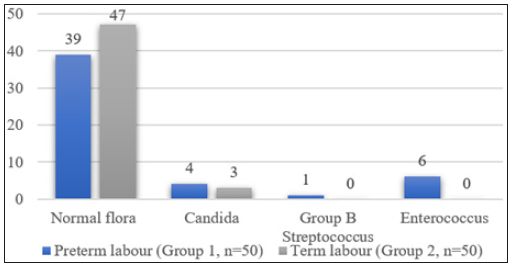

Figure 2:High vaginal swab culture.

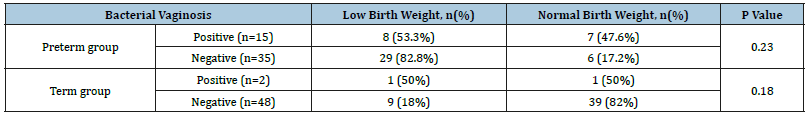

Table 3:Comparison of birth weight in both the groups.

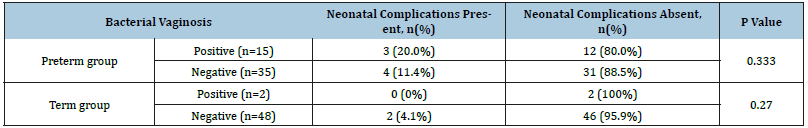

Table 4:Comparison of neonatal complications in both the groups.

Table 5:Comparison of postpartum complications in both the groups.

Significantly a greater number of patients in preterm labour group tested positive on vaginal swab culture sensitivity as compared to term labour group (p=0.048) as shown in Figure 2. In preterm group 53.3% of neonates born to BV positive mothers had low birth weight as compared to 82.8% of neonates born to BV negative mothers. This difference was not significant statistically (p=0.230). In term group 50% of neonates born to BV positive mothers had low birth weight as compared to 18% of neonates born to BV negative mothers. This difference was not significant statistically (p=0.180) as shown in Table 3. In preterm labour group 20% of neonates born to BV positive mothers had neonatal complications as compared to 11.4% of neonates born to BV negative mothers. This difference was not significant statistically. In term labour group no neonates of BV positive mothers had neonatal complications, while 4.1% of neonates of BV negative mothers had neonatal complications. The difference was not significant statistically as shown in Table 4. In preterm labour group 26.6% of patients who were BV positive had postpartum complications as compared to 22.8% of patients who were BV negative (Table 5). This difference was not significant statistically (p=0.333). In term labour group none of the patients who were BV positive had post-partum complications, while 12.5% of patients who were BV negative had post-partum complications (p=0.270).

Discussion

The mean maternal age in both the groups was comparable (25.6 years and 25.3 years in preterm labour group and term labour group respectively). A similar study done by Chawanpaiboon et al. [4] had a mean maternal age of 26.7 years and 26.6 years respectively [4]. Both the groups had equal number of primigravida’s and multigravidas. In the study done by Chawanpaiboon et al. [4] the preterm group had 60% primigravidas and 40% multigravidas while the term group had 51.8% primigravida’s and 48.2% multigravidas.

The mean gestational age at admission in preterm group was 33.5 weeks in term group and 39.0 weeks in preterm group. The mean gestational age at admission in the study done by Chawanpaiboon et al. [4] was 33.6 weeks and 38.6 weeks in preterm and term groups respectively [4].

In preterm labour group 12% of patients had previous history of sexually transmitted infections as compared to 2% in term labour group. In the present study the most common sexually transmitted infection reported was Trichomoniasis. According to the results of the largest prospective study in the USA, T. vaginalis was significantly associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery [12]. Azargoon et al. [13] showed that there was no significant correlation between T. vaginalis with preterm labor birth.

The preterm group had significantly a greater number of patients with different grades of discharge as compared to term group (72% vs. 50% respectively). Various studies have proved that lower genital tract infections are very common among apparently healthy-looking pregnant women with an overall prevalence of 40- 54% [14].

The number of patients who fulfilled Amsel’s criteria for diagnosis of BV were more in preterm group (30%) as compared to term group (4%). This observation correlated with other studies where it was concluded that BV is one of the important risk factors for preterm labour. Hillier et al. [15] and Subtil et al. [16] showed that patients with BV were 40% more likely to have preterm delivery.

In the present study bacterial vaginosis was diagnosed in 30% of the patients who presented with preterm labour. Mittal et al. [17] and Svare et al. [18] showed 30% and 16% prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in preterm group.

The number of patients having vaginal discharge suggestive of bacterial vaginosis in preterm labour group were significantly more than in term labour group (28% vs. 4% respectively). In the study conducted by Chawanpaiboon et al. [4] discharge suggestive of bacterial vaginosis was present in 24% and 25% of patients with preterm labour and term labour respectively.

Preterm group had a greater number of patients with basic vaginal pH as compared to term group (44% vs.14%). The number of patients having a positive Whiff test in preterm group was significantly more as compared to term labour group (44% vs.18%). In the present study clue cells were not detected in either of the two groups. Absence of clue cells can be explained by the possibility of them having chronic infection in which clue cells were absent due to local immune response to IgA antibodies. According to Easmon et al. [19] it is not always necessary to see clue cells to make a diagnosis of BV and it is not included in the scoring system by Nugent which is more systematic and has a specificity of 95%.

The number of patients who had other genital tract infections (vaginal swab culture sensitivity tested) were more in preterm group as compared to term group (22% vs. 6%). The commonest infections found in this study were Enterococcus (12%) followed by Candida (8%) and Group B Streptococcus (2%) in preterm group and Candida (7%), Enterococcus (6%) and Group B Streptococcus (1%) in term labour group. Benchetrit et al. [20] showed the presence of GBS colonization in 26% pregnant women evaluated. Simões et al. [21] studied Candida albicans and found a prevalence of 19.3% for vaginal candidiasis in normal pregnant women in the third trimester.

Microbiota that inhabit the vagina play an important role in the spread of illnesses and the maintenance of a healthy genital tract. The correlation between upper genital infections (UGIs) during pregnancy and the possibility of infection in the newborn is high. Thus, as a first step towards the understanding of infection in newborns, it is imperative to determine the prevalence of microbial colonization in the pregnant women. The mean C- Reactive Protein value recorded in preterm labour group was 1.287 and in term labour group it was 0.748. In the study done by Halder A et al. [22] out of 250 patients, 78 (31.2%) were CRP positive and 172 (68.8%) were CRP negative. CRP positivity showed positive association with preterm labour with odds ratio 2.384 (95% CI: 1.153-4.928 & p value 0.01).

Hillier et al. [15] showed the relation of BV with a significantly reduced mean birth weight. Svare et al. [18] showed lower mean birth weight in bacterial vaginosis. In the present study however a greater number of neonates born to preterm BV negative group (82.8%) had low birth weight as compared to neonates born to preterm BV negative mothers (53.3%). This can be explained by the probability of factors other than BV responsible for low birth weight like anaemia and malnutrition which was present in 22 and 16 patients respectively in the present study.

In preterm labour group 26.6% of patients who were BV positive had postpartum complications as compared to 22.8% of patients who were BV negative; the most commonly seen complication was puerperal pyrexia. In term labour group none of the patients who were BV positive had post-partum complications, while 12.5% of patients who were BV negative had post-partum complications. Out of the patients who had complications five patients had puerperal pyrexia and one patient had atonic PPH. This finding probably suggests the possibility of factors other than BV giving rise to post-partum complications in term women. In the present study 3 patients in term labour group had viral fever and one of them had malarial fever.

Eschenbach and co-workers were among the first researchers who studied the relationship between bacterial vaginosis and preterm labour. In their study, 49% in preterm group and 24% in full term group had bacterial vaginosis. Later they showed the correlation between bacterial vaginosis and chorioaminiotis and preterm labour [23]. Prematurity Prediction Study carried out on 3000 women in the United States has shown the relationship between bacterial vaginosis and preterm labour [24]. Nejad et al. [25] carried out a study to establish the association of bacterial vaginosis and preterm labour, on 160 patients in Iran in 2008, reporting 25% prevalence of BV in patients with preterm labour and 11.3% prevalence in term patients [25]. In the present study bacterial vaginosis was diagnosed in 30% of patients with preterm labour and 4% of patients in term labour.

Conclusion

The current observational study clearly demonstrates the causation and the temporal association of bacterial vaginosis with preterm labour. Therefore, the screening for bacterial vaginosis as a routine during pregnancy and its prompt treatment may reduce the risk of preterm labour. Proper hygiene, early diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis and its prompt treatment may therefore reduce the risk of preterm labour and neonatal complications.

References

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Gilstrap JCHL, Wenstrom KD (2010) Preterm Birth. In: Gorda P (Ed.), William’s Obstetrics, 22nd edn, McGraw-Hill, USA, pp. 855-873.

- Vause S, Johnston T (2000) Management of preterm labor. BMJ 83(2): F79-F85.

- Beverly A, Pool D (1998) Preterm labour: Diagnosis and treatment. American Family Physician 57(10): 2457-2464.

- Chawanpaiboon S, Pimol BNK (2010) Bacterial vaginosis in threatened preterm, preterm and term labour. J Med Assoc Thai 93(12): 1351-1355.

- Gregor JA, French JI (2000) Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 55(5): S1-19.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2001) ACOG practice bulletin. Assessment of risk factors for preterm birth. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 31, October 2001. Obstet Gynecol Oct 98(4): 709-716.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins Obstetrics (2003) ACOG practice bulletin. Management of preterm labor. Number 43, May 2003. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 82(1): 127-135.

- Ugwumadu A, Manyonda I, Reid F, Hay P (2003) Effect of early oral clindamycin on late miscarriage and preterm delivery in asymptomatic women with abnormal vaginal flora and bacterial vaginosis: A randomized controlled trial. Lancet 361(9362): 983-988.

- Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KCS, Eschenbach DA, et al. (1983) Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiological associations. Am J Med 74(1): 14-22.

- Speigel CA, Amsel R, Holmes KK (1983) Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis by direct Gram Stain of vaginal fluid. J Clin Microbiol 18(1): 170-177.

- Speigel CA, Amsel R, Eschenbach DA, Schoenknecht F, Holmes KK (1980) Anaerobic bacteria in nonspecific vaginitis. N Eng J Med 303(11): 601-607.

- Giraldo PC, Araujo ED, Amaral RLG, Passos MRL, and Gonsalves AK (1997) The Prevalence of Urogenital & Sex Transm Dis 24: 353-360.

- Azargoon A, Darvishzadeh S (2006) Association of bacterial vaginosis, trichomonas vaginalis, and vaginal acidity with outcome of pregnancy. Arch Iran Med 9(3): 213-217.

- Kirschbaun T (1992) Antibiotics in the treatment of preterm labor. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynae society 168(4): 1239-1246.

- Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, Krohn MA, Gibbs RS, et al (1995) Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. The vaginal infections and prematurity study group. N Engl J Med 333(26): 1737-1742.

- Subtil D, Denoit V, Gouëff F, Husson MO, Trivier D, et al. (2002) The role of bacterial vaginosis in preterm labor and preterm birth: a case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 101(1): 41-46.

- Sangita, Mittal AS, Chandra P, Gill AK (1999) Incidence of Gardnerella vaginalis in preterm labour. Obs and Gynae Today 4(5): 299-303.

- Svare JA, Schmidt H, Hansen BB, Lose G (2006) Bacterial vaginosis in a cohort of danish pregnant women: prevalence and relationship with preterm delivery, low birthweight and perinatal infections. BJOG 113(12): 1419-1425.

- Easmon CS, Hay PE, Ison CA (1992) Bacterial vaginosis: A diagnostic approach. Genitourin Med 68(2): 134-138.

- Benchetrit LC, Francalanza SE, Peregrino H, Camelo AA, Sanches LA (1982) Carriage of streptococcus agalactiae in women and neonates and distribution of serological types: A study in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol 15(5): 787-790.

- Simoes JA, Giraldo, Filho ADR, FaundesA (1996) Prevalencia e fatores de risco associados` a infecoes c´ ervicovaginais durante a gestac¸˜ ao,”Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia & Obstetr´ıcia 18(6): 459-467.

- Halder A, Agarwal R, Sharma S, Agarwal S (2013) Predictive significance of C reactive protein in spontaneous preterm delivery: a prospective cohort study. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2(1): 47-51.

- Newton ER, Piper J, Peairs W (1997) Bacterial vaginosis and intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 176(3): 672-677.

- Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Cotch MF (2002) Obstetrics and Gynecology 99(3): 419-425.

- Nejad VM, Shafaie SJ (2008) The Association of Bacterial Vaginosis and Preterm Labor. Pak Med Assoc 58(3): 104-106.

© 2019 Kavya K. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)