- Submissions

Full Text

Integrative Journal of Conference Proceedings

Mood Stabilizer Vs Third Generation Antipsychotic: A Double-Blind Clinical Trial in Acute Mania

Shoja Shafti S*

Department of Psychiatry, Iran

*Corresponding author: Shoja Shafti S, Department of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Iran

Submission: February 03, 2020;Published: February 26, 2020

Volume2 Issue2February, 2020

Abstract

Objective: While prescription of lithium has been limited in recent years due to its adverse effects and necessity for frequent laboratory tests, second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are introduced as helpful medications for acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Comparing lithium with aripiprazole in a group of patients with diagnosis of acute mania was the objective of the present trial.

Methods: 30 male inpatients with diagnosis of bipolar I disorder were entered into a four-week, doubleblind study for random assignment to lithium carbonate (800-1200mg/day) or aripiprazole (20-30mg/ day) (n=15 in each group). While Manic State Rating Scale (MSRS) was the main outcome measure in the present assessment, other scales such as Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale (BRMS), Schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI) and Clinical Global Impressions-Global Improvement scale (CGI-G) have been used as secondary outcome measures.

Results: While at the end of assessment and in comparison with baseline frequency and intensity of symptoms reduced significantly in both groups (p<0.05), improvement was significantly more remarkable by lithium compared with aripiprazole (p<0.01). Also, while CGI-G demonstrated significant improvement by both of them (p< 0.04 for aripiprazole & p< 0.002 for lithium), BRMS and SAI showed significant amelioration only in the lithium group (p<0.001& p<0.000, respectively).

Conclusion: Though both aripiprazole and lithium were helpful for improvement of manic symptoms, treatment with lithium was more advantageous.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder; Acute mania; Lithium; Aripiprazole

Introduction

Bipolar and related disorders are separated from the depressive disorders in DSM-5 and placed between the chapters on schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders and depressive disorders in recognition of their place as a bridge between the two diagnostic classes in terms of symptomatology, family history, and genetics [1]. The bipolar I disorder criteria represent the modern understanding of the classic manic-depressive disorder or affective psychosis described in the nineteenth century, differing from that classic description only to the extent that neither psychosis nor the lifetime experience of a major depressive episode is a requirement [1]. However, the vast majority of individuals whose symptoms meet the criteria for a fully syndromal manic episode also experience major depressive episodes during the course of their lives [1]. According to ICD -10, in mania, mood is elevated out of keeping with the individual’s circumstances and may vary from carefree joviality to almost uncontrollable excitement. Elation is accompanied by increased energy, resulting in overactivity, pressure of speech, and a decreased need for sleep [2]. Normal social inhibitions are lost, attention cannot be sustained, and there is often marked distractibility. Self-esteem is inflated and grandiose or over-optimistic ideas are freely expressed [2]. Perceptual disorders may occur, such as the appreciation of colors as especially vivid (and unusually beautiful), a preoccupation with fine details of surfaces or textures, and subjective hyperacusis. The individual may embark on extravagant and impractical schemes, spend money recklessly, or become aggressive, amorous, or facetious in inappropriate circumstances [2]. Little information exists on specific cultural differences in the expression of bipolar I disorder. One possible explanation for this may be that diagnostic instruments are often translated and applied in different cultures with no transcultural validation [2]. In one U.S. study, 12-month prevalence of bipolar I disorder was significantly lower for Afro-Caribbean’s than for African Americans or whites. A family history of bipolar disorder is one of the strongest and most consistent risk factors for bipolar disorders [2].

There is an average 10-fold increased risk among adult relatives of individuals with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Magnitude of risk increases with degree of kinship. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder likely share a genetic origin, reflected in familial co-aggregation of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [2]. The bipolar disorder is often misdiagnosed in particular among outpatients with recurrent depression. Indeed, the unrecognized bipolar disorder is common among depressed outpatients, who are younger, unemployed, single or divorced with a low socio-economic level. Also, the under-diagnosis bipolar disorder seems to be related with the earliest onset age of a depressive episode and more prevalent in depressed patients with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [3]. Terrible consequences of a manic episode often result from loss of insight, hyperactivity and poor judgment [1]. While the lifetime risk of suicide in individuals with bipolar disorder is estimated to be at least 15 times that of general population, it may account for one-quarter of all completed suicides [1]. Early onset bipolar disorder, in comparison with the later-onset form, shows graver psychosociological consequences, and is characterized, as well, by rapid cycling and increased risks of suicide attempts and substance abuse [4]. Pharmacotherapy is the treatment of choice for acute mania with the primary goal of rapid control of dangerous behavior, aggression and agitation. Todays, along with lithium, the usage of which has been limited in recent years due to its adverse effects and necessity for frequent laboratory tests, First Generation Antipsychotics (FGAs), like haloperidol, and Second Generation Antipsychotics (SGAs), like aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone are most widely employed in the treatment of bipolar disorder [4,5]. Among SGAs, aripiprazole, with convincing evidence as a very operative treatment alternative in the controlling of acute manic and mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder [6,7], has been increasingly used , as well, in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder and received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication in 2005 [8].

Furthermore, aripiprazole, as adjunctive to either valproate or lithium, has appeared to be equally safe and effective combinations for the treatment of bipolar disorder [9]. Aripiprazole has been widely used in the management of psychiatric disorders. Dissimilar to other FGAs that mostly have variable degrees of dopamine D2 receptor antagonism, aripiprazole is a partial agonist at dopamine D2 and D3, and serotonin 5-HT1A, and exhibiting antagonistic action at the 5-HT2A and H1 receptors [6,7], which may explain obvious differences in tolerability profiles [10]. Moreover, though the drug is associated with sedation, weight gain and extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), the incidence of EPS over twelve weeks was not significantly different between aripiprazole (10mg/day) and placebo [10]. In a comparative study by Keck et al. [11], aripiprazole (15-30mg/day) showed substantial amelioration of acute mania, and the extent of its improvement was comparable with lithium [11]. Also, in another study by El-Malloch et al. [12], aripiprazole monotherapy (15-30mg/day) appeared to be as useful as lithium (900-1500mg/day) for the extended treatment of mixed or manic episodes [12]. Similar standpoint, as well, has been taken by Dhillon [7], who concluded that based on existing guiding principle, aripiprazole is a first-line alternative for the short-term management of mania [7]. Nonetheless, while aripiprazole seems to be a valuable treatment for mania, since comparative studies between aripiprazole and other mood stabilizers are few, so the precise place of aripiprazole in therapy demands further studies [4,13]. So, objective of the present assessment was comparing aripiprazole vs. lithium in a group of eastern patient population, with their own specific pharmaco-genetic or ethnopsychopharmacologic characteristics, who met the diagnosis of acute mania.

Method

Thirty male inpatients with diagnosis of bipolar I disorder,

according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

5th edition [1], who had been admitted to the hospital due to

relapse or new emergence of an episode of acute mania, were

entered into a 4-week, double-blind study, for random assignment

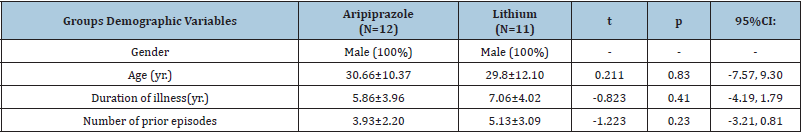

to aripiprazole or lithium carbonate (Table 1). Informed consent

was given by the participant or a legal representative. The study

was approved by the ethics committee of the academy. Exclusion

criteria were mixed episode, suicidal ideation, severe instability or

aggression, substance abuse, neurological and other severe medical

illnesses, previous treatment with antidepressants or long acting

antipsychotics (depot). The assessment had been accomplished as

a double-blind design, while the patients, staff and assessor were

unaware of the prescribed drugs that were packed into identical

capsules. While the patients in the first group (n=15) were given

aripiprazole (5mg uncoated tablets), the cases in the second group

(n=5) were prescribed lithium carbonate (300mg uncoated tablets).

Both of these medicines were given according to practice guidelines

and standard titration protocols. Supplier of the aforesaid drugs

was the hospital’s pharmacy, and the medications were in generic

forms. While prescription of lorazepam, as sedating agent, was

permissible in the course of evaluation, no other anticonvulsant or

supplementary antipsychotic was allowable during the assessment.

Furthermore, except than standard care, no additional psychosocial

intervention, like psychotherapy, was acceptable during trial. Manic

State Rating Scale (MSRS) was the main outcome measure in the

present assessment, which had been scored at baseline and weekly

intervals up to the fourth week.

The MSRS is an instrument planned for measurement of

severity of manic symptoms. The 26 items in this scale are each

given a frequency score on a 0 to 5 gauge and an intensity score

on a 1 to 5 gauge. Inter-rater reliability for each item has been

reported to range from 0.89 to 0.99 [14]. Similarly, severity of manic

symptoms, insight, and overall illness severity had been rated using

the Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale (BRMS, as double-check) [15],

Schedule for Assessment of Insight (SAI) [16] and Clinical Global

Impressions-Global Improvement scale (CGI-G) [17], respectively.

The aforesaid measures had been scored by the same experienced unaware psychiatrist in both groups. Mean modal dosages of

aripiprazole and lithium in this trial were 25.83mg/day (SD=4.93)

and 981.81mg/day (SD=161.34), respectively. In addition, mean

serum level of lithium was 0.8±0.147 mill-equivalents per liter.

Mean dosage of adjunctive lorazepam, as well, was 4.5±1.11mg/

day for the aripiprazole group and 4.18±0.93mg/day for the lithium

group, with no significant difference (t=0.746, p<0.46, 95%CI:-0.57,

1.21).

Statistical analysis

Patients were compared regarding baseline characteristics by means of t tests. Treatment effectiveness, which had been assessed by MSRS, had been analyzed by t test and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), for intra-group analysis, and Splitplot (mixed) design ANOVA, for between-group analysis. BRMS, SAI and CGI-G, which had been scored at baseline and the end of the 4th week, had been analyzed by t test. Also, Cohen’s effect size (ES), for measurement of the strength of effectiveness, and power of the study (Post-hoc), for evaluation of Type II error, had been analyzed. Statistical significance had been defined as p value ≤0.05. MedCalc Statistical Software version 15.2 was used as statistical software tool for analysis.

Result

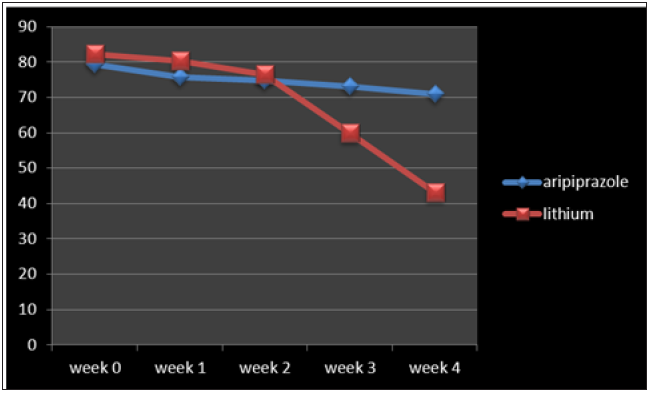

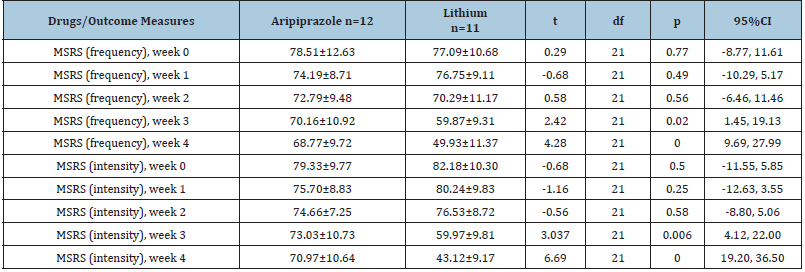

While three patients (20%, n=3) in the aripiprazole group and four patients (26.66%, n=4) in the lithium group left the study during the first half of the assessment due to unwillingness or adverse effects of the prescribed drugs, analysis for efficacy was based on data from a comparable number of patients in both groups (z=0.43; p<0.66; CI 95%=0.36, 0.23). The groups were equivalent regarding the baseline characteristics (Table 1). Mean total score of MSRS improved significantly by both lithium and aripiprazole at the end of 4th week (Table 2) (Figures 1 & 2). This was in spite of the fact that improvement in the aripiprazole group seemed to be faster initially, but it was surpassed by lithium after a short period. With respect to the intensity of manic symptoms, at the end of the trial 41.66% (n=5) of patients in the aripiprazole group and 63.63% (n=7) of cases in the lithium group displayed at least 25% decrease in mean total scores of MSRS, in comparison with baseline, and more than 50% improvement was evident in 8.3% (n=1) and 45.45% (n=5) of patients of the aforesaid groups, respectively. Between-group analysis displayed significant advantage of lithium, regarding both frequency and intensity, at the end of 3rd and 4th week (Table 2).

Figure 1: Changes of MSRS (frequency) between baseline and week 4.

Figure 2: Changes of MSRS (intensity) between baseline and week 4.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants.

Table 2: Between-group analysis of primary outcome measure at 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th week.

>

Abbreviations: MSRS: Manic State Rating Scale

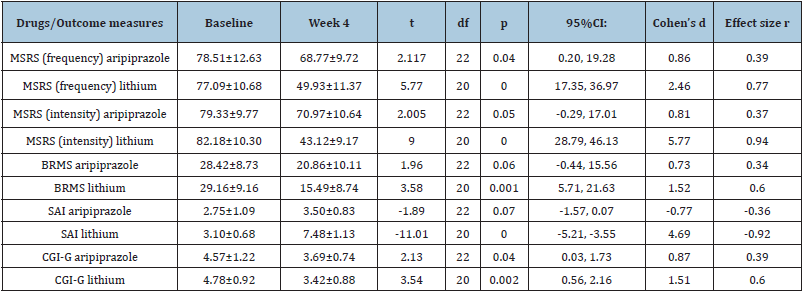

Table 3: Intra-group analysis of different outcome measures between baseline and 4th week, plus effect -size analysis.

Abbreviations: MSRS: Manic State Rating Scale; BRMS: Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale; SAI: Schedule for Assessment of

Insight; CGI-G: Clinical Global Impressions-Global Improvement scale

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed significant and non-significant changes in frequency and intensity of MSRS, respectively, in the aripiprazole group, and significant changes in both of the aforesaid variables in the lithium group [F (4, 55)=2.37 p<0.05 SS=429.22 MSe=45.36 and F (4,50)=3.75 p<0.009 SS=1629.14 MSe=108.48, for frequency, and F (4,55)=2.08 p<0.07 SS=968.77 MSe=116.18 and F (4,50)=4.88 p<0.002 SS=3264.97 MSe=167.15 for intensity of symptoms in the aripiprazole and lithium groups, respectively]. Split-plot (mixed) design ANOVA also showed significant difference between them [F (9,110)=2.67 p<0.007 SS=8562.58 MSe=356.31 for frequency and, F (9,110) =2.80 p<0.005 SS=8497.93 MSe=337.74, for intensity of the symptoms, respectively]. Moreover, while mean total score of BRMS showed significant improvement in the lithium group with a reduction around 46.87%, it was not so regarding aripiprazole with an improvement about 26.60%. The same situation was true regarding SAI, with significant improvement by lithium and insignificant improvement by aripiprazole (Table 3). However, at the end of trial the CGI-G demonstrated significant improvement by aripiprazole and lithium (Table 3). Moreover, since the sample size was not great, the effect size (ES) was analyzed regarding alterations on the MSRS (frequency and intensity) at the end of treatment, which showed large improvement (“d=or >0.8” or “r=or>0.3”) with both of them (Table 3). The main reported side effects of aripiprazole in the related group were inner unrest (n=4, 33.33%), mild stiffness (n=3, 25%), and sedation (n= 3, 25%). The major adverse effect of lithium in the associated group was tremor (n=5, 41.66%). Post-hoc power analysis showed a power = 0.31 on behalf of the present assessment, which changed to power = 0.72 in the frame of compromise power analysis.

Discussion

Although many individuals with bipolar disorder return to a

fully functional level between episodes, approximately 30% show

severe impairment in work role function [2]. Functional recovery

lags substantially behind recovery from symptoms, especially with

respect to occupational recovery, resulting in lower socioeconomic

status despite equivalent levels of education when compared

with the general population. Individuals with bipolar I disorder

perform more poorly than healthy individuals on cognitive tests

[2]. Cognitive impairments may contribute to vocational and

interpersonal difficulties and persist through the lifespan, even

during euthymic periods. The lifetime risk of suicide in individuals

with bipolar disorder is estimated to be at least 15 times that of

the general population. In fact, bipolar disorder may account for

one-quarter of all completed suicides [2]. A past history of suicide

attempt and percent days spent depressed in the past year are

associated with greater risk of suicide attempts or completions.

Incomplete interepisode recovery is more common when the

current episode is accompanied by mood incongruent psychotic

features [2].

People with a history of childhood sexual or physical abuse

appear to be more at risk, and to have a worse prognosis [2].

Long-term functional prognosis (work, family, etc.) (Particularly in

untreated patients) is almost as poor as in schizophrenia. There is

an overall increase in premature mortality, only partially explained

by a suicide rate of 10% [18]. Currently, no convincing evidence

suggests that atypical antipsychotic medications are superior

to typical medications for the treatment of psychosis. However,

atypical antipsychotic medications may be more acceptable due to

fewer symptomatic adverse effects in the short term. While little

evidence is available to support the superiority of one atypical

antipsychotic medication over another, side effect profiles are

different for different medications. For example, while treatment

with olanzapine, risperidone and clozapine is often associated with

weight gain.

Aripiprazole is not associated with increased prolactin or

with dyslipidemia. In addition, whereas adolescents may respond

better to standard-dose as opposed to lower-dose risperidone, with

respect to aripiprazole and ziprasidone, lower doses may be equally

effective. Consequently, uniform ways of reporting, in future studies,

will be an indispensable stratagem for achievement of inclusive

consensus among researchers [13,19]. Back to our study, while in

intra-group analysis aripiprazole and lithium were statistically and

significantly useful in amelioration of manic symptoms, lithium

was significantly more effective than aripiprazole in betweengroup

analysis after four weeks, which was clearly evident at the

end of 3rd week, too. Such a state of affairs is somewhat consistent

with the insignificant improvement of intensity of symptoms by

aripiprazole. The same inference, as well, is valid regarding final

outcome of secondary measures like BRMS and SAI, despite the

fact that it was not so with regard to CGI-G, which was significantly

improved in both groups. Perhaps it could be expressed that while

improvement in the aripiprazole group was statistically significant,

from a pragmatic perspective, it was more evident in the lithium

group. Hence, it is obvious that such a finding, which could not be

in complete agreement with the findings of Keck et al. [11] and

El-Mallakh et al. [12], who had found aripiprazole comparable to

lithium for management of acute mania [11,12], make it hard to

determine that which one is better than other.

Similarly, it is not in harmony with Dhillon [7], who concluded

that based on existing guiding principle, aripiprazole is a first-line

alternative for the short-term management of mania [7,10], and

as a first-line or second-line alternative for stopping the relapse of

mood episodes in the course of longer-term treatment [7,20,21];

although he believes that additional evaluations for comparing

aripiprazole with other medications, including SGAs, are

required and would aid to conclusively determine the position of

aripiprazole in relation to other drugs [21]. Then again, the existing

evidence does not support the effectiveness of aripiprazole for the

management of bipolar depression and stopping its relapse [22], a

capability that is conceivable by lithium [23]. Similarly, while some

believe that, based on an insufficient amount of direct comparisons,

antipsychotic drugs (haloperidol or SGAs) may have shown

greater efficacy or faster action than mood stabilizers like lithium,

valproate and carbamazepine [19], others believe that there are

not essentially enough studies comparing lithium with SGAs [5].

Moreover, in the study of El-Mallakh et al. [12] Of the 66 patients

who entered the study, only 20 patients completed the entire phase,

and based on 60% drop-out rate of the patient population, their trial

could not be supposed, statistically, powered enough for precise

clinical judgment [12]. Similarly, while recently in the Europe,

oral aripiprazole was approved for the treatment of moderate

to severe manic episodes in adolescents with bipolar I disorder,

another time due to high drop-out ratio, effectiveness during

long-term treatment (over 30 weeks) could not be verified [10].

Additional different outcomes are available regarding comparing

lithium with other anti-manic agents. For example, in a doubleblind

study on forty female inpatients meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria

for acute mania, while both olanzapine and lithium were found to

be significantly helpful in the improvement of manic symptoms,

lithium was significantly more effective than olanzapine [24]. Also,

in another study, while both lithium and valproate were effective for improvement of manic symptoms, lithium was significantly

more effective than valproate [25]. Likewise, though the results

of several assessments strongly show that many anti-manic drugs

are significantly more useful than placebo, their comparable effect

sizes and overlapping confident intervals make it hard to determine

that which one is better than other. In addition, modern medical

practice, generally influenced by additional factors like cost and

time, regularly use a combination of anti-manic agents to bring

mania under control as fast as possible-especially combinations of

antipsychotics and mood stabilizers [19].

Though the findings of the present assessment are not in

agreement with aforementioned surveys, employment of various

outcome measures, different techniques of analysis, dissimilar

durations of treatment, various sample sizes, different treatment

dosages, and unalike patient cohorts (sex, age, duration of illness,

number of episodes, smoking state and pharmacological as well

as other pre-treatments) should not be ignored, due to their

possible influence on the results of the individual investigations.

Additionally, it should not be disregarded that possible pharmacogenetic

or ethno-psychopharmacologic differences, between

western and eastern people, may have influenced the outcome of

the present assessment. But, in spite of contradictory results, when

we notice the similar findings regarding superiority of lithium over

other SGAs [24] or mood stabilizers [25], we can conclude that

the results of the present assessment regarding stronger effect of

lithium on frequency and intensity of symptoms, is nothing except

than restating of an important clinical fact, which could have been

overlooked due to hurried inferences.

Our findings pertaining to adverse effects, as well, were not

precisely similar to the result of a former study by El-Mallakh et

al. [12], who had found nasopharyngitis, headache and somnolence

in their samples due to aripiprazole. Although the fear of lithium

toxicity and its narrow therapeutic index may encourage a lot of

clinicians to choose more innocent medications similar to SGAs,

availability of precise laboratory checking of serum level of lithium

and judicious employment of standard physical and laboratory

checkups may encourage doctors to modify their perspective

regarding lithium. Small sample size, short duration of evaluation,

gender-based sampling, and exclusion of mixed episodes were

among the weaknesses of this trial.

Conclusion

Though both aripiprazole and lithium were helpful for improvement of manic symptoms, treatment with lithium was more advantageous.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. In: (5th edn), Washington DC, American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, USA, pp: 123-132.

- Neel Burton (2010) Psychiatry. (2nd edn), John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Oxford, UK, pp: 89-120.

- Bouchra O, Maria S, Abderazak O (2017) Screening of the unrecognised bipolar disorders among outpatients with recurrent depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study in psychiatric hospital in Morocco. Pan Afr Med J 27: 247.

- Brown R, Taylor MJ, Geddes J (2013) Aripiprazole alone or in combination for acute mania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12: CD005000.

- Tohen M, Vieta E (2009) Antipsychotic agents in the treatment of bipolar mania. Bipolar Disord 11(2): 45-54.

- Sayyaparaju KK, Grunze H, Fountoulakis KN (2014) When to start aripiprazole therapy in patients with bipolar mania. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 10: 459-470.

- Dhillon S (2012) Aripiprazole: A review of its use in the management of mania in adults with bipolar I disorder. Drugs 72(1): 133-162.

- Tsai AC, Rosenlicht NZ, Jureidini JN, Parry PI, Spielmans GI, et al. (2011) Aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a critical review of the evidence and its dissemination into the scientific literature. PLoS Med 8(5): e1000434.

- Vieta E, Owen R, Baudelet C, McQuade RD, Sanchez R, et al. (2010) Assessment of safety, tolerability and effectiveness of adjunctive aripiprazole to lithium/valproate in bipolar mania: A 46-week, open-label extension following a 6-week double-blind study. Curr Med Res Opin 26(6): 1485-1496.

- McKeage K (2014) Aripiprazole: a review of its use in the treatment of manic episodes in adolescents with bipolar I disorder. CNS Drugs 28(2): 171-183.

- Keck PE, Orsulak PJ, Cutler AJ, Sanchez R, Torbeyns A, et al. (2009) Aripiprazole monotherapy in the treatment of acute bipolar I mania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and lithium-controlled study. J Affect Disord 112(1-3): 36-49.

- El-Mallakh RS, Marcus R, Baudelet C, McQuade R, Carson WH, et al. (2012) A 40-week double-blind aripiprazole versus lithium follow-up of a 12-week acute phase study (total 52 weeks) in bipolar I disorder. J Affect Disord 136(3): 258-266.

- Kumar A, Datta SS, Wright SD, Furtado VA, Russell PS (2013) Atypical antipsychotics for psychosis in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10: CD009582.

- Beigel A, Murphy DL, Bunney WE (1971) The manic-state rating scale: Scale construction, reliability, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiat 25(3): 256-262.

- Bech P, Bowling TG, Kramp P (1979) The Bech-Rafaelsen mania scale and the Hamilton depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 59(4): 420-430.

- David AS (1990) Insight and Psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 156: 798-808.

- Guy W (1976) Clinical Global Impressions ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology, Rockville, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, DHEW publication NO.(ADM), USA, pp. 76-338.

- Katona C, Cooper C, Robertson M (2012) Psychiatry at a glance. (5th edn), John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Oxford, UK, pp: 24-25.

- Yildiz A, Vieta E, Leucht S, Baldessarini RJ (2011) Efficacy of antimanic treatments: Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 36(2): 375-389.

- Yatham LN, Fountoulakis KN, Rahman Z, Ammerman D, Fyans P, et al. (2013) Efficacy of aripiprazole versus placebo as adjuncts to lithium or valproate in relapse prevention of manic or mixed episodes in bipolar I patients stratified by index manic or mixed episode. J Affect Disord 147(1-3): 365-372.

- McIntyre RS (2010) Aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder: A review. Clin Ther 32(suppl 1): s33-s38.

- Yatham LN (2011) A clinical review of aripiprazole in bipolar depression and maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 128 (suppl1): s21-s28.

- Harrison P, Geddes J, Sharpe M (2011) Lecture Notes: Psychiatry. (10th edn), Wiley-Blackwell, United Kingdom, pp. 100-101.

- Shafti SS (2010) Olanzapine vs. lithium in management of acute mania. J Affect Disord 122(3): 273-276.

- Shafti SS, Shahveisi B (2008) Comparison between lithium and valproate in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 28(6): 718-720.

© 2020 Shoja Shafti S. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)