- Submissions

Full Text

Integrative Journal of Conference Proceedings

A Study on Skill Development and Productivity of the Workforce in Indian Economy

Pradeep Kumar Panda*

School of Social Sciences, India

*Corresponding author:Pradeep Kumar Panda, Doctoral Scholar Economics, School of Social Sciences, India

Submission: May 13, 2019;Published: May 24, 2019

Volume1 Issue3May, 2019

Abstract

This paper analyses the current scenario of skilled workforce of Indian Economy and future requirement of skill development. The paper also outlines skill gap in various sectors, the key issues and policy implications to address those issues and challenges in Skill Development and Productivity arena. Today, India is one of the youngest nations in the world with more than 62% of its population in the working age group (15-59 years), and more than 54% of its total population below 25 years of age. Its population pyramid is expected to bulge across the 15-59 age group over the next decade. It is further estimated that the average age of the population in India by 2020 will be 29 years as against 40 years in USA, 46 years in Europe and 47 years in Japan. In fact, during the next 20 years the labour force in the industrialized world is expected to decline by 4%, while in India it will increase by 32%. This poses a formidable challenge and a huge opportunity. To reap this demographic dividend which is expected to last for next 25 years, India needs to equip its workforce with employable skills and knowledge so that they can contribute substantively to the economic growth of the country. As India moves progressively towards becoming a global knowledge economy, it must meet the rising aspirations of its youth. This can be partially achieved through focus on advancement of skills that are relevant to the emerging economic environment. The challenge pertains not only to a huge quantitative expansion of the facilities for skill training, but also to the equally important task of raising their quality. Skills development is the shared responsibility of the key stakeholders viz. Government, the entire spectrum of corporate sector, community-based organizations, those outstanding, highly qualified and dedicated individuals who have been working in the skilling and entrepreneurship space for many years, industry and trade organizations and other stakeholders. The policy links skills development to improved employability and productivity in paving the way forward for inclusive growth in the country. The skill strategy is complemented by specific efforts to promote entrepreneurship in order to create ample opportunities for the skilled workforce. Skilling need to be an integral part of employment and economic growth strategies to spur employability and productivity. Coordination with other national macroeconomic paradigms and growth strategies is therefore critical.

Keywords:Skill development; Productivity; Entrepreneurship; Labour force; Indian economy

Introduction

Skill development is an important driver to address poverty reduction by improving employability, productivity and helping sustainable enterprise development and inclusive growth. It facilitates a cycle of high productivity, increased employment opportunities, income growth and development. However, this is just one factor among many affecting the productivity whose measurement differs for individuals, enterprise and economy. The increase in productivity could be due to availability of skilled & healthy manpower; technological up gradation and innovative practices; and sound macroeconomic strategies. The manifestations of improved productivity can be in the form of improvement in real gross domestic product (economy), increased profit (enterprises) and higher wages (workers). This study is looking into the relationship between skill development and productivity with focus on India. However, to begin with it is necessary to understand what constitutes productivity and how it is measured at different levels. Productivity which explains an input-output relationship is a crucial factor whose benefits can be distributed in several different ways such as better wages and working conditions to workforce; increased profits and dividend to shareholders; environmental protection; and increase in revenue to Governments. This helps both the enterprise and country to remain competitive in the domestic and global market respectively [1-10].

The increase in productivity can be attributed to varied reasons such as new technology, new machines, better management practices; investment in plant and equipment and technology, occupation safety improvement in the skill level of workers; macroeconomic policies, labour market conditions, business environment and public investment in infrastructure and education. Therefore, it is evident that skill development is just one factor necessary for the productivity growth and it needs to be an integral part of the development policies. The policies should address the levels of development and need and requirement of various sectors. Besides this the skill policy should focus on improving access, quality and relevance of training for different segments and sectors. The evidence from developed countries suggests that investment in education and skills helps economy to move to high growth sectors and break the low wage, low skill development syndrome.

Different countries at different levels of development face different challenges. In the context of developing economies like India the challenge is to meet the skilled manpower requirement of the high growing sectors on the one hand through better synergy between employers and the training providers, increased investment in the training infrastructure and also to ensure that the informal economy also have skilled manpower wherein the informally trained skills are recognized and certified and that entrepreneurship training is provided for moving to formal sector. The workplace training plays an important role in productivity enhancement but in the developing economies the huge informal economy poses a challenge which could be addressed by developing clusters or lead firm taking the initiative which would help achieving economies of scale in the skills development; development of competencies within and between firms and availability of lead firm facilities. This would make available skilled manpower by the lead firm as per its requirement and the small enterprise would improve their productivity. The Government can facilitate linkages among various companies and stimulate adoption of technologies and skill upgrading programs [11-20].

The linking of skills and productivity would not only benefit the enterprise and economy but would also facilitate different segments of the population particularly the marginalized sections of the society to reap the benefits of the economic growth through skill development. The lack of access to education and training or the low quality or relevance of training keeps the vulnerable and marginalized sections into the vicious circle of low skills and low productive employment. The national skill policy provides a framework to ensure access to various target groups to realize their potential for productive work and contribute in economic and social development. However, different approaches need to be adopted which may overlap as groups are not mutually exclusive such as improving agriculture marketing ex-tension; investing in rural infrastructure; making available quality education; on the job and targeted training for the disabled and identifying the requirement of migrant workers. The question is how one links the skill development to future challenges to address the demand of the growing economies.

The National Skill Development policy provides for integration of skill development into the national development polices such as developing infrastructure, reducing poverty and decent work agenda. The diagram below explains the relationship between skill development strategy for productivity, employment and sustainable development.

It emerges that coordination among various stakeholders, coherence in sectoral, macro and skill policies, knowledge sharing and effective participation of trade unions and employers along with technology development is central to any development strategy. The participation by all stakeholders would strengthen move towards skilled economy. It would also ensure that small enterprises get access to training services and developing their managerial capabilities for growth. It also emerges that while coherence is necessary, it is also necessary (repetition) to ensure gender equality, upgrade technology, and diversify production structure, building up individual competencies and collecting/dissemination of information on future requirements as also available supply. This would improve availability of skilled manpower and reduce the supply mismatch.

This paper analyses the current scenario of skilled workforce of Indian Economy and future requirement of skill development. the paper also outlines skill gap in various sectors, the key issues and policy implications to address those issues and challenges in skill development and productivity arena. data is obtained from NSSO data base and various published sources of Indian Economy [21- 24].

Study finding

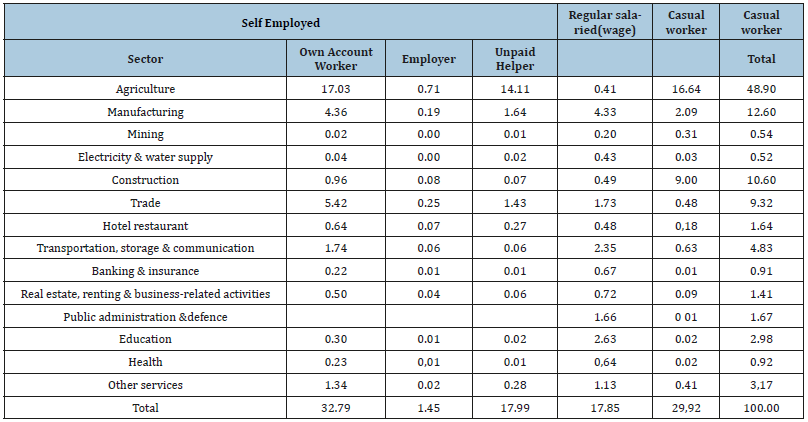

Labor market: As compared to other developed and developing countries, India has a unique window of opportunity for an- other 20-25 years called the demographic dividend. If India is able to skill its people with the requisite life skills, job skills or entrepreneurial skills in the years to come the demographic advantage can be converted into the dividend wherein those entering labour market or are already in the labour market contribute productively to economic growth both within and outside the country. But meeting this objective is a daunting task as India faces the challenge of skilling large labour force that is largely illiterate or below primary and unskilled. The structural transition from the agricultural to the non-agricultural sector has seen rapid decline in the contribution of farm sector to the GDP to 16% but a very slow decline in the workforce participation level to 48% resulting in the low level of productivity in the agricultural sector. The nature of jobs created is informal (91% of the workforce) and the status of employment is self-employed. Further, there is the high degree of unemployment among the youth due to aspirational mismatch or skill mismatch, declining participation of females in the labour force and an economic environment wherein jobs are not created commensurate with the economic growth. The distribution of the workforce by sector and status of employment shows that in agriculture sector where almost 32% is self-employed majority is operating as ownaccount worker or unpaid helper (Tables 1). After agriculture the proportion of those working as self-employed is Trade (7%) and manufacturing (6%). In these two sectors also the proportion of workforce working as own account workers are more than those working as employers.

Tables 1:Properties of workforce employed by status (2011-12).

The proportion of those working as casual labour is higher in agriculture (17%) followed by construction (9%) and manufacturing (2%). overall, about 52% of the total workforce was self-employed, of which own-account workers accounted for 33% and the unpaid helper 18%. The proportion of workforce with regular wage or salary was just 18% and 30% were casually employed. When we talk about productivity it only covers those who are in the regular wage or salaried employment. The selfemployed operating as own account workers are mostly household enterprises assisted by unpaid helpers. In this type of employment, the productivity levels are low, working conditions poor, wage employment is totally absent. On the other hand, if the own account workers can be upgraded to becoming an employer by providing skill development and other logistic support, it leads to creation of further wage employment and enhancement of their productivity.

Relationship between literacy and poverty reduction

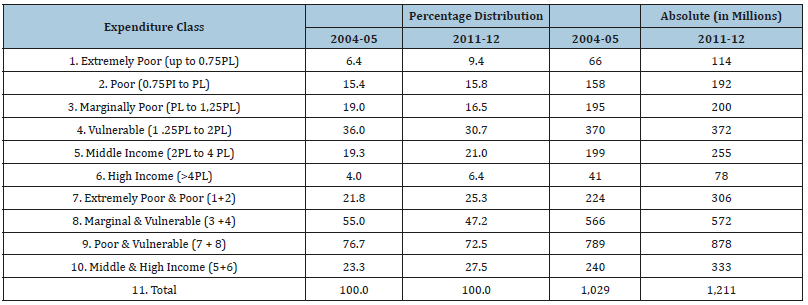

The preponderance of self-employment mainly in agriculture is mostly due to their low education and skill levels stimulated by their poor economic background. The proportion of population up to the poverty line i.e. the extremely poor and poor increased from 21.8% in 2004-05 to 25.3% in 2011-12. But the proportion of the marginally poor and the vulnerable decreased from 19% to 16.5% and from 36% to 30.7% between 2004-05 and 2011-12. overall 72.5% of the population fall in the category of poor and vulnerable in 2011-12 as compared to 76.7% in 2004-05, a decrease of 4.2 points (Tables 2).

Tables 2:Population in different expenditure class.

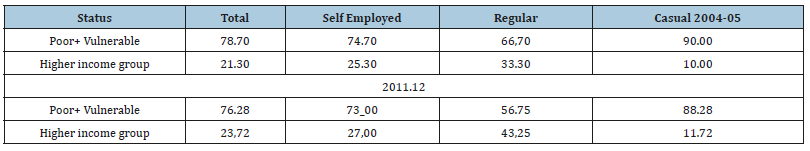

Tables 3 shows the distribution of the unorganized workers across different expenditure class. It may be seen that 76.28% belong to the poor & vulnerable category in 2011-12 as compared to 78.7% in 2004-05, a decline of 2.42 points. This relatively low level of living of the workforce brings out the quality of employment which calls for a look at their educational and skill qualification.

Tables 3:Percentage distribution of unorganized workers across expenditure classes.

Linkages between skill development, productivity and employment potential

Skill development is the focus area of the government policy. It is central to accessing employment in the formal sector and enhancing productivity in the informal economy for reducing poverty and risk of underemployment. The National Policy on Skill Development aims to train about 104.62 million people afresh and additional 460 million are to be reskilled, upskilled and skilled by 2022. Considering that majority of these labour force would be self or casual employed, the challenge is to how to improve the skill levels of these workforce. These categories cut across various target groups or vulnerable sections of the society. The groups are not mutually exclusive and there are overlaps because the workers in the self-employed category are a heterogeneous lot while the casual employed may be intermittently employed and in different unskilled works.

The lack of access to good education and training keeps the vulnerable and the marginalized sections into the vicious circle of low skills; low productive employment and poverty. The marginalized group which includes rural poor, youth, persons with disabilities, migrant workers and women constitute the highest number of poor. In India, 70% of the labour force reside in rural areas and depend on low productive agricultural activity where there is huge underemployment leading to low level of productivity. The high proportion living in poverty among women in India is due to their concentration in low productivity work.

The skill strategy needs to focus on strategy of skill development should be aimed at addressing the skill needs of the self-employed as well as the casual employed. According to Economic Survey 2013- 14, “India can increase its long-term trend growth by unleashing the entrepreneurial spirit of millions across the country by strengthening the economic freedom of the people.” In accordance, the National Policy on Skill Development & Entrepreneurship 2015 emphasises on entrepreneurship development as the pathway for creating more wage employment and in turn growth of the economy.

The policy has identified following policy strategy for promoting entrepreneurship:

A. Educate and equip potential and early stage entrepreneurs across India

B. Connect entrepreneurs to peers, mentors and incubators

C. Support entrepreneurs through Entrepreneurship Hubs (E-Hubs)

D. Catalyse a culture shift to encourage entrepreneurship

E. Encourage entrepreneurship among the underrepresented groups

F. Promote entrepreneurship amongst women

G. Improve ease of doing business

H. Improve access to finance and

I. Foster social entrepreneurship and grassroots innovations.

Skill development of the self-employed is essential to make the transition from own account workers to employers or entrepreneurs. The success of the major programmes of the current Government viz; Make in India, Digital India, Smart City, Namami Gange, Swachh Bharat depends on the success of the Skill India Mission in skilling and reskilling 460 million by 2022.

The skill development programmes to promote entrepreneurship are also equally important namely

A. SETU- the Self-Employment and Talent Utilization scheme which is a Techno-Financial, Incubation and Facilitation Program to support all aspects of start-up businesses, and other selfemployment activities, particularly in technology- driven areas,

B. Atal Innovation Mission AIM an innovation promotion platform involving academics, entrepreneurs, and researchers drawing upon national and international experiences to foster a culture of innovation, R&D in India and

C. Start Up India to promote bank financing for start-ups and offer incentives to boost entrepreneurship and job creation in the country.

Current and future skill requirements for India

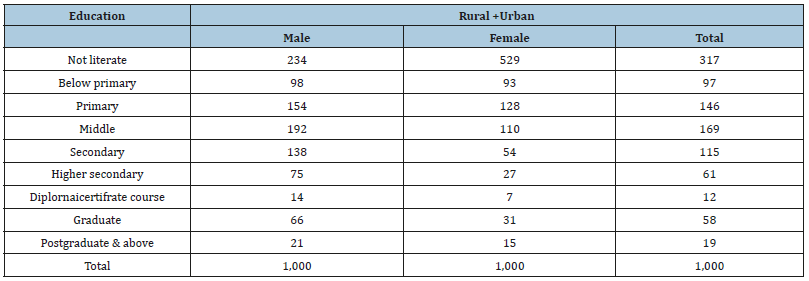

Nearly 56% of the workforce in 2011-12 had basic education upto primary and the proportion of low literacy levels was high among the female workforce (75% below primary) as compared to the males. The proportion of total workforce with educational qualification secondary was just 11.5% while for the female workforce it was still lower at 5.4%. (Tables 4). Education level wise distribution of Workforce. As regards skill training, 75.8% of the workforce did not have any skill training during 2011-12 while the proportion of workforce with formal training was only 3.05%. The proportion of workforce that received training through informal modes was 12.46%. (Tables 5).

Tables 4:Education level wise distribution of work force.

Tables 5:Vocational training profile of the work force.

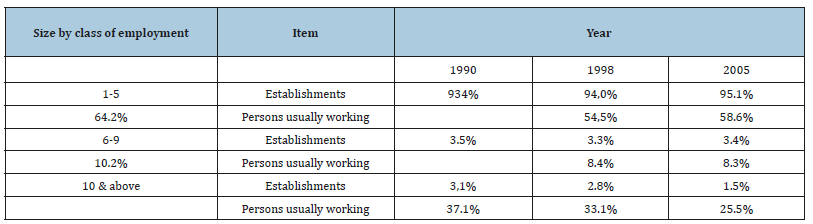

From Tables 4 & 5 the education and vocational profile of the workforce throws light on the challenge that India faces if the labour force consisting of existing and new entrants are to be provided age appropriate skill training which might include skilling, reskilling and upskilling. With such low skill levels, the profile of our enterprise is such that nearly 95% of the units are micro in size engaging less than 5 workers. The challenge therefore lies in expanding the size of the enterprises to beyond 5 in number so that the progression of growth of the enterprises from being a single employer to that of being a partnership or private corporate entity takes place. Unless this transition is in place the productivity levels will not improve and neither will employment (Tables 6).

Tables 6:Establishment by size class of employment.

Some estimates of skill gaps in different sectors

In analyzing the skill gap, there exist two types of low educated labour force entering the labour market due to their poor economic conditions and remaining unskilled. One is the educated labour force who are not able to find jobs matching their qualification due to lack of technical or soft skills. This is the reason for the high rate of educated unemployment among the youth. To reduce the skill gap among the educated there is the need for better quality education, knowledge of English language, on the job training as well as better job information. India’s skill gaps rests on weak conceptual foundations. While some industries do suffer from real skill gaps, others are constrained by commercial difficulties that maybe better addressed through policies other than skill development programs.

According to The India Skills report 2015, India has to achieve the target of skilling/upskilling 150 million people by 2022. He further explains skill gap as ‘the phrase skill gap refers to redefining the relationship between education, industry and business.’ In simple terms a skill gap can be defined as the difference between the skills needed for a job versus those skills possessed by a prospective worker. The Ministry of Skill Development & Entrepreneurship has estimated the estimated incremental human resource requirement across 24 sectors as 109.73 million by 2022. The Institute of Applied Manpower Research in their Occasional Paper ‘Estimating Skill Gap on a Realistic Basis for 2022’ arrive at an incremental skilled manpower requirement of 291 million by 2022. But they point out two major problems for those already in the workforce. First, is the poor quality of those who have general education up to secondary level or those having vocational training (including postsecondary level technical education), and hence employability. The second problem that employers are known to complain about is the mismatch between the skills that are currently available in the educated or trained labour force on the one hand, and the type of skills that are actually in demand from employers, on the other. This supply-demand mismatch and the quality problem will have to be addressed over the course of the next decade simultaneously with a very sharp quantitative expansion in capacity of those to be educated or vocationally trained.

Countries that have succeeded in linking skill development to gains in productivity, employment and development have targeted skill development policy towards three main objectives: (i) matching supply to current demand for skills (ii) helping workers and enterprises adjust to change; and (iii) building and sustaining competencies for future labour market needs. The first objective is about the relevance and quality of training. Matching the provision of skills with labour market demand requires labour market information systems to generate, analyze and disseminate reliable sectoral and occupational information, and institutions that connect employers with training providers. It is also about equality of opportunity in access to education, training, employment services and employment, in order that the demand for training from all sectors of society is met. The second objective is about easing the movement of workers and enterprises from declining or low-productivity activities and sectors into expanding and higher productivity activities and sectors. Learning new skills, upgrading existing ones and lifelong learning can help workers to maintain their employability and enterprises to adapt and remain competitive. The third objective calls for a long-term perspective, anticipating the skills that will be needed in the future and engendering a virtuous circle in which more and better education and training fuels innovation, investment, technological change, economic diversification and competitiveness, and thus job growth. To achieve the above-mentioned objectives convergence across policies is essential. Skill development and employment policy should be inter-linked. The full value of one policy can be realised only if it supports the objectives of the other policy. For investments in skill development to yield maximum benefit to workers. Enterprises and for the economy, the country’s capacity for coordination is most important in three areas

A. Connecting basic education to technical training, technical training to labour market entry, and labour market entry to workplace and lifelong learning;

B. Ensuring continuous communication between employers and training providers so that training meets the needs and aspirations of workers and enterprises; and

C. Integrating skill development policies with other policy areas – not only labour market and social protection policies, but also industrial, investment, trade and technology policies, and regional or local development policies.

Policies to promote skill development and support formalization of economic activity

On the education front, the Right to Education Act, 2009 has been introduced which legislates compulsory education up to the age of 14 years. Thereafter to prevent dropouts the government is promoting the dual system of education from Class IX (secondary level) onwards. Credit facility is now being made available for students who want to pursue vocational education after completing Senior Secondary. The National Skill Qualification Framework has been introduced to facilitate the smooth transition from general education to vocational education and vice versa at all levels from 2014 onwards.

For the labour force already in market with lack of education and any training, Recognition of Prior Learning introduced in 2014 to get accreditation for the skills they already possess based on which they can go for up-skilling or re-skilling. The amendment to the Apprentices Act 1961 encourages even the micro and small entrepreneurs to engage apprentices which would improve the availability of skilled manpower.

Under the National Skill Development Mission introduced in 2014, the skill training of the heterogeneous labour force consisting of youth, women, school dropouts, disabled, minorities, tribal groups are mandated. Since employment opportunities are limited and not everyone would get the jobs, the MUDRA scheme introduced in Union Budget 2015-16 would help in entrepreneurship development through availability of refinance facilities which would enable the MSME units’ access to cheap credit. Besides there is the NABARD which provides refinance facilities to the cooperative lending institutions which provide credit to the farmers.

To bring in financial inclusion the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana introduced in 2015 to facilitate opening of accounts by all citizens with zero balance. The Government cash transfers would be made through these accounts, which would check on leakage at various levels of implementation. Besides holding the account also gives the benefits of accident insurance and life insurance. The launch of DIGITAL India would make information technology available even in the rural inaccessible areas which in turn would facilitate in providing business services such as availability of markets, cheap raw materials, skilled labour through services such as email, SMS, Facebook, whats up etc.

The social protection floor as per definition does not exist in India. But at any time, there are schemes open to the entire population covering both the formal and informal sector. Though there are legislation based and program based social security schemes the nature of coverage is based on voluntary participation. Under legislation based social security schemes there is the Employees’ Provident Fund, Employees’ Deposit Linked Insurance Scheme, Employees’ Pension scheme, Employees’ Health Scheme under ESIC. All these being contributory schemes employees and employers in the micro & small sector seem to evade them. The program schemes open to the general population include IGNOPs, Atal Pension Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana and Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana etc. But their coverage is not cent percent due to lack of awareness, disinterest or illiteracy. The National Health Mission (Rural & Urban), Indira Gandhi Matritva Sahyog Yojana, Integrated Child Development Scheme, Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girl etc. are schemes open to the general population for betterment of their health and nutrition.

India has the Minimum Wages Act 1948 in implementation immediately after independence. Right now, it is not uniformly applicable to all occupations but only to certain occupations where there are 1000 or more workers in a State. The low skilled informal jobs done as own account workers are not covered by minimum wages right now. Through the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005, the issue of distress employment in rural areas has been addressed to a large extent. The above analysis indicates that skill ecosystem has been created and polices are put in place for linkages and achieving high employment potential. But for this strategy to work something more needs to be done to plug the gaps.

Conclusion and Policy Suggestions

To conclude for skill development to be a driver of productivity requires improvement in quality, relevance and accessibility of training by all the sections of population particularly marginalised and poor with poor education level. The key question that requires immediate answers are how to measurer contribution of skill development to productivity and employment growth; what policies support enterprise development; what is the role of various stakeholders; skill mapping for a country of India size on local levels and how to strengthen the coordination between different institutions for better results. There is need for robust data base on different parameters such as wages in the farm and non -farm sector, data for computing GVA for informal economy as defined by the National Commission for Unorganized Sector Enterprises.

Following are some of the policy suggestions: Improving the Education level of the Labour Force: The current labour market data as given in Tables 4 clearly indicates the low level of education of labour force wherein about 80% has education up to secondary with about 29% as illiterates. The universalization of elementary education has improved the enrolment and the retention up to the upper primary level. However, there is sharp dropout after that. There is need to universalize the secondary education so that young boys and girls are prepared for working productively in agriculture or to access alternative employment opportunities. The school dropouts need to be provided the second chance to acquire basic numeracy and literacy skills to move them out of low paid un- skilled work in the informal economy. There are examples in India such as Pratham which initiated the Second Chance program in 2011 to give dropout students, especially girls, a chance to complete their Secondary School education and acquire the skills necessary for employment. It is a 15-month program that targets young girls and women between the age of 16-25 years who have dropped out of school and helps them pass their Secondary School Examination. Apart from that it also aims to raise awareness about educating girls and women so that they can break the regressive barriers of caste and religion. This would not only remove the barriers that girls face in going to schools but would also improve the employability of women.

Improving access to quality training for employment opportunities: There is need to improve the access of quality and relevant training by all including marginalized section particularly in the rural areas to raise productivity and income and to link opportunities for better livelihood and employment. In the India context this is very important as the large pool of the demographic advantage resides in the rural areas. This may require increase in the training capacities for relevant and high-quality skills and require responding to rapidly changing skills needs; upgrading informal apprenticeship systems i.e. Apprenticeship Prathapan Yojana to deliver skills and knowledge for value added activities and more advanced technologies. The Recognition of Prior Learning needs to be speeded up for the effective and efficient matching of workers’ skills with skills required in the jobs to reduce the skill gap. This way equal opportunities can be created both for women and men to access relevant/ quality education, vocational training and workplace learning, and to productive and decent work So that they can realize their potential and contribute to economic and social development and maintain not only their employability but also sustainability of enterprises. However, improving access also necessitates creating system to collect and communicate reliable and up to date information on skills needs in current labour markets for better informed choices and career guidance. In the rural setting efforts are made through MGNERGA to coordinate training provision with priorities set for rural development and to promote such non -farm rural activities which help in generating rural income and manage distress arising out of the seasonal fluctuations in the agricultural sector. Also, the improved production practices using new technologies, alternative crops, labour intensive crops can have positive income and employment effect in the small land holdings. The provision of safe transportation, female instructors, childcare facilities, market and finance would encourage women participation. Last but not the least the skill needs to be made apparitional by engaging with local bodies/NDGO and using all kinds of media.

Coordination among various stakeholders: Today there is disconnect among various stakeholders leading to skill mismatch. Though efforts are made through Sector Skill councils to address the gaps, but still there is a long way to go. The coordination between Ministries and Agencies responsible for policy design and implementation in the areas for education and skills development would help in equipping young women and men with the skills required by emerging industries and jobs and help in adjustments during periods of change. This would achieve not only the objective of policy coherence but also address issues of skill gaps, boost productivity, improve employment growth etc. However, this also requires good macro-economic policies that support employment opportunities. In the Indian case, the programs like Make in India, Digital India, Housing for All and Swatch Bharat together with favorable polices for infrastructural development, lower interest rates would offer huge employment opportunities supported by National Skill Mission.

Strengthening skill delivery framework: Most training is implemented at the state level. However, the implementation varies across states with many demographically advantageous states facing not only shortage of physical infrastructure but also quality training. The State Skill Development Missions (SSDMs) in the States should evolve into a coordinating body to harmonize the skilling efforts across line departments/ private agencies/ voluntary organizations etc. and ensure that funds received under various programs are optimally utilized. The common norms for course cost durations etc as announced at the central level needs to be adopted by the states and state-specific guidelines for skill development programs should be made accordingly. Further for effective outreach and access by different segments of the population it is necessary to have decentralized implementation at state, district and block level and to ensure effective coordination and monitoring of skill development initiatives. The existing pat- tern of DRDA to coordinate skill efforts at district level may be considered for adoption for effective coordination and interaction with local self-government, civil society, training provider, industry and other stakeholders. Given that state conditions and requirements vary, it is necessary to determine sectoral priorities at State level based on sectoral assessment and the formulation of appropriate policies to enhance the qualitative and quantitative skill availability for the sector based on conduct of regular skill surveys. The inter-linkage of the SSDMs with the industry, training providers, sector skill Councils, NSDA should be maintained at the policy formulation and implementation level. The sector skill councils should to assist the States to align training pro- gram with NSQF. If required a working group could be constituted with SSCs representatives in this regard.

Focus on outcome and determining key performance indicators: Today focus is on number metrics with minimal or no tracking of the students trained and placed. The union government initiatives in strengthening the national career guidance centre at the district and block level and integrating it with the labour market information system would facilitate in tracking the youth receiving skill training who may work either as wage employed or self-employed. The success stories can be shared through LMIS/ national career service centers so that it provides a medium for the youth to explore the possibilities of its up-scaling/replication.

Strengthening private sector participation: Given that target to be achieved is huge and resources with the government are limited, there is urgent need to incentivize industry to be to either set up training institutions in PPP mode in industry clusters to facilitate availability of trained manpower for big and MSME units or to adopt existing government ITIs and Polytechnics. The industry may also be encouraged to provide their work benches for training their staff as teacher. The teachers and students can be given exposure on the shop floor. Industry can also enter flexi MOUs based on sector, trade or institutions and offer work benches for practical training. Further the local industry can be actively involved for curriculum development, provision of equipment’s, training of trainers, opening incubation centers particularly in the rural areas.

Availability of financial resources and systemic reforms: The scale of the problem is too big requiring huge resources. The need of the hour is to consolidate resources at all levels and create a national training fund to be accessed by all but operated by Ministry of skill development on priority basis. The funds could be bilateral/ multilateral donations, CSR funds, welfare funds etc. Together with finances it is also necessary to speed up implementation of National Skill Qualification Framework; Putting in place robust Labour Market information System for effective dynamic interventions and creation a pool of trainer’s assessors for quality and reliable outcome-based training.

References

- Ashton D, Green F (1996) Education, training and the global economy.: Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, France.

- Asian Development Bank (2008) Education and skills: strategies for accelerated development in Asia and the pacific. Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines.

- Desai SB (2010) Human development in India: challenges for a society in transition. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Galihardi R (2004) Statistics on investment in training, skills working, Geneva, Switzerland. Paper No.18.

- Government of India (2011) Census of India 2011: Provisional population totals, of 2011. Rural-Urban Distribution. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, GOI, Delhi 2: 1.

- Government of India (2015) National skill development and entrepreneurship development policy India 2015, Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, Delhi, India.

- International Labour Organization (ILO) (2008) Skills for Improved productivity, employment growth and development, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Johansson R, Adams A (2004) Skills development in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Regional and Sectoral Studies. ORLD Bank, Washington DC, USA.

- Kuruvilla S, Erickson CL, Hwang A (2002) An assessment of the Singapore skills development system: does it constitute a viable model for other developing countries. World Development 30(8): 1461-1476.

- Middleton J, Ziderman A, Adams A (1993) Skills for Productivity: Vocational education and training in developing countries. New York, Oxford University Press, USA.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) (2017) India Yearbook 2017. NCERT, Delhi, India.

- NITI Aayog (2015) Report of the sub-group of chief ministers on skill development. NITI Aayog, New Delhi, India.

- OECD (1997) Industrial competitiveness in the knowledge-based economy: The new role of governments. OECD Proceedings, Paris.

- Okada A (2006) Skills formation for economic development in India: fostering institutional linkages between vocational education and industry. Manpower Journal, India (4): 71-95.

- Okada A (2005) Bangalore’s software cluster. In: Akifumi Kuchiki and Masatsugu Tsuji (Eds.), Industrial clusters in Asia: Analyses of their competitiveness and cooperation. New York, USA, pp. 244-277.

- Okada A (2004) Skills development and interfirm learning linkages under globalization: Lessons from the Indian automobile Industry, World Development 32(7): 1265-1288.

- Paul B (2011) Demographic dividend or deficit: Insights from data on Indian labor paper presented at the 3rd Annual conference of the academic network for development in Asia (ANDA), Nagoya, Japan.

- Pratham (2017) Annual status of education report: Rural 2017. New Delhi, India.

- Standing G (1993) Global labor flexibility: seeking distributive justice. MacMillan, Basingstoke, UK.

- UNESCO (2012) EFA global monitoring report 2012, youth and skills. Putting Education to Work. UNESCO, Paris.

- World Bank (2017) World Development Report 2017 Jobs. Washington DC, World Bank, USA.

- World Bank (2017) South Asia development matters: more and better jobs in south Asia. Washington DC, World Bank, USA.

- World Bank (2017) Skills development in India: The vocational education and training system. Washington, D.C, World Bank, USA.

- World Bank (2007) Decent Work agenda in poverty reduction strategy papers: Recent developments, committee on employment and social policy, Governing body 300th Session Geneva, Washington DC, World Bank, USA.

© 2019 Pradeep Kumar Panda. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)