- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Acute Pancreatitis in Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome: Case Report

Jessica Abou Chaayaa1, Nourhane Obeidb2, Ali Abdallahc3 and Mona Hallakd4*

1Internal Medicine Resident, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut Lebanon

2Gastroenterology Fellow, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut Lebanon

3Radiology Fellow, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut Lebanon

4Gastroenterology Physician, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut Lebanon

*Corresponding author: Mona Hallakd, Gastroenterology Physician, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut Lebanon

Submission:March 21, 2022;Published: April 25, 2022

ISSN 2637-7632Volume6 Issue5

Abstract

Objective: This paper aims to describe the presentation of acute pancreatitis secondary to superior mesenteric artery syndrome in a patient with major weight loss.

Method: We present a case report and briefly review the literature.

Results: A 16-year-old female patient with a recent history of weight loss presented with acute onset of vomiting and abdominal pain. She was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis secondary to superior mesenteric artery syndrome attributed to anatomical change caused by the loss of the fat pad between the mesenteric artery and the duodenum.

Conclusion: Acute pancreatitis can be caused by superior mesenteric artery syndrome in patients with weight loss. This paper can present clinical awareness and prompt early diagnosis in these patients.

Keywords: Acute pancreatitis; Superior mesenteric artery syndrome; Weight loss

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a clinical diagnosis in patients presenting with epigastric pain radiating to the back with nausea and vomiting combined with elevated serum levels of pancreatic enzymes [1]. It results from inflammation and auto-digestion of the pancreatic tissue. In acute pancreatitis, acinar cell death occurs by both necrosis and apoptosis [2]. There are many causes of acute pancreatitis that can be identified in most patients. The most common etiology is obstruction of the common bile duct by gallstones. Other possible reasons are hypertriglyceridemia, alcohol abuse, hypercalcemia, secondary to Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and pancreas divisum [3]. The diagnosis requires two of the following three features: epigastric abdominal pain, serum amylase and/ or lipase more or equal to 3 times the upper limit of normal, and characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on CT scan [4]. On the other hand, superior mesenteric artery syndrome is a rare form of upper intestinal obstruction in which the third part of the duodenum is compressed by the overlying superior mesenteric artery [5]. In our case, acute pancreatitis was attributed to superior mesenteric artery syndrome which very few cases were reported through the literature.

Case Presentation

Our patient is a 16-year-old female patient previously healthy presented to our institution with two months history of postprandial epigastric pain. The patient reported that she started experiencing these symptoms after having intentionally lost 20Kg within 4 months and becoming 50Kg now with a height of 170cm (current BMI 17.3Kg/m2). The pain is sudden in onset postprandially increasing in intensity in the epigastric area non radiating associated with nausea and belching. The patient experienced multiple episodes of vomiting postprandially relieving her symptoms. This affected her quality of life during the past two months leading to a decrease in PO intake and fear of eating leading to additional weight loss. Two days before presentation, the patient started having constant epigastric pain radiating to her back and nausea and vomiting with minimal food intake and decreased bowel movements. A review of the systems is pertinent for amenorrhea of two months duration, noting that the patient is not sexually active and is not on hormonal medications. Upon presentation to our emergency department, a physical exam showed normal bowel sounds, a soft abdomen with minimal tenderness in the epigastric area, no rebound tenderness, negative murphy, and McBurney signs.

Table 1: Summary of the case.

Pancreatic enzymes were drawn showing lipase of 548U/L (more than three times ULN) and amylase of 275U/L (more than three times ULN) with the liver enzymes and function tests being within the normal range. Lipid panel, electrolytes, and other labs were normal. The patient was diagnosed with pancreatitis of unknown etiology. To note, this is the first documented pancreatitis the patient ever had, and she denied any such previous symptoms before weight loss. B-HCG was done to rule out pregnancy as a cause of amenorrhea and before any diagnostic imaging. Computed tomography scan with intravenous contrast was ordered showing significant over-distention of the stomach as well as the proximal duodenal loops before reaching the D3 segment where compression was suspected between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta, and normal pancreas (Grade A on Balthazar score for radiological severity of pancreatitis). Findings were suggestive of superior mesenteric artery syndrome with the aortomesenteric angle estimated to be around 12.8 degrees as shown in the figure below (Normal range being between 28-65 degrees). The gallbladder was under distended, no gallstone was detected in the gallbladder or common bile duct, no intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation. The patient was admitted to the hospital for mild acute pancreatitis and was put on adequate hydration and kept NPO. On day one of hospitalization, the patient underwent an ultrasound showing gallbladder adequately distended with normal wall thickness, and no gallstones or sludge were seen. No intrahepatic biliary dilatation or pericholecystic fluid with negative sonographic Murphy’s sign was found. Gastroscopy was done with normal results. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography ruled out pancreatic divisum as a possible cause of acute pancreatitis in a young healthy patient. The patient was started on a liquid diet being very well tolerated with gradual progress reaching a full liquid diet over the next two days. The patient was then discharged home on a full liquid diet. Unfortunately, she returned a few days later after starting on solid regular food due to the recurrence of the postprandial epigastric pain caused by sudden ingestion of a large amount of solid food. Upon this second admission, the patient was started on total parenteral nutrition (peripheral nutrition) with mashed food initially being tolerated and switched to a small amount of solid food. The patient was advised to gain weight of at least eight Kg with a dietitian and to be followed as an outpatient (Table 1).

Discussion

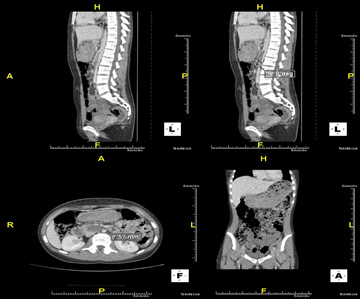

The superior mesenteric artery syndrome is characterized by the compression of the duodenum between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. This leads to upper gastrointestinal obstruction with abdominal pain nausea, bilious vomiting, and weight loss [5]. The obstruction is located at the third part of the duodenum D3 which is located between the major vessels [6]. The superior mesenteric artery forms an angle with aorta ranging normally between 25 and 60 degrees [7]. Loss of mesenteric fat between the superior mesenteric artery and the duodenum by any cause leads to a more acute angle thereby leading to compression [5]. Common causes include significant weight loss either intentional or not, anatomical variant or congenital abnormality of the intestine, origin of the superior mesenteric artery or ligament of Treitz, external compression or medical conditions, or surgical procedures that cause mesenteric tension or intraabdominal compression [7]. The gold standard for diagnosis is the distention of the stomach with the proximal parts of the duodenum and a transition zone at the 3rd part of the duodenum. Plain abdominal films will usually reveal findings of bowel obstruction, gastric distention, and dilation of the proximal duodenum with an abrupt vertical cutoff of air in the third part of the duodenum. A contrast-enhanced CT scan additionally demonstrates the aortomesenteric angle, distance and fat tissue, obstruction of the duodenum, and potential compression. Contrast-enhanced CT scan and MR angiography seem to be equivalent in evaluating the exact angle and distance [8]. Recently, the ultrasound power color Doppler imaging was used for detection of this reduced aortomesenteric angle in suspected cases [9]. In our case, the patient refused a plain radiograph with oral contrast, but a CT scan of the abdomen along with MRI/MRCP was done showing the result mentioned above. The management is conservative initially targeting the etiology. Weight gain is advised with nutritional support, correction of electrolyte disturbances, and gastric decompression. Refractory cases are treated with surgical intervention such as Strong procedure which frees the duodenum by dividing the ligament of Treitz; gastrojejunostomy or duodenojejunostomy [10]. Our patient presented with acute pancreatitis with an underlying diagnosis of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Acute pancreatitis is the acute inflammation of the pancreatic tissue through autodigestion by the pancreatic enzymes [2]. Most common etiologies include gallstones, alcoholism, hypertriglyceridemia. Infections include viral causes such as cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, and tuberculosis. Genetic risk and autoimmune disease are also possible reasons mainly in recurrent pancreatitis in young patients. Rare causes include hypercalcemia, medications, and anatomic pancreatic anomalies. This 16-year-old patient was a healthy female with no medication history, denying recent infection such as upper respiratory tract or urinary tract, and reports no alcohol consumption. On the review of systems, the patient denied neurological, rheumatological, respiratory, urological, or other manifestations of the skin or lymph node disease. She only reported amenorrhea for the past two months. Upon investigations, MRCP was done and showed no signs of pancreas divisum or anatomical abnormalities within the biliary tract. No gallstones were found on a Computed Tomography scan or ultrasound imaging. The aorto-mesenteric angle of 12.8 degrees was measured on a computed tomography scan (Figure 1). Lipid panel including triglyceride level was normal. Cytomegalovirus IgM, Toxoplasma IgM, and purified protein derivative skin testing were all normal. Calcium level was also within the normal range during hospitalization. IgG4 panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and anti-nuclear antibodies level were all within normal range. Genetic testing was not done since this was the first episode of pancreatitis.

Figure 1: Sagittal computed tomography demonstrating a narrow aorto-mesenteric angle (12.8degrees). Axial computed tomography demonstrating a reduced aorto-mesenteric distance of 7mm (normal between 10 and 34mm), causing duodenal compression and dilation of the proximal portion of the duodenum. Coronal computed tomography showed marked dilation of the stomach.

The etiology of acute pancreatitis in our patient was initially unknown. After reviewing the literature, few cases were found to be related to superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Noting that our patient has a matching history, clinical and imaging findings compatible with SMA syndrome, and clinical and laboratory findings of acute pancreatitis without significant radiological findings, the diagnosis of pancreatitis was attributed to SMA syndrome. The exact pathophysiology is still unknown, and few cases were reported. Multiple mechanisms were proposed. First, malnutrition will cause pancreatic cell atrophy along with dilatation of the ducts. In addition, it causes a highly oxidative environment leading to damage and an increase in inflammatory mediators. The second mechanism suggests that a retrograde flow from the duodenum will lead to pancreatic duct injury and cell damage causing pancreatitis. The retrograde flow was explained by the compression caused by the superior mesenteric artery [11].

Conclusion

As shown in this case, with few other case reports, superior mesenteric artery syndrome is described mainly in patients with anorexia nervosa due to sudden loss of fat pad hence decreasing the aortomesenteric angle to less than 30 degrees causing gastric outlet obstruction and thus can lead to secondary acute pancreatitis by two proposed mechanisms. The first is malnutrition-induced oxidative stress and an increase in inflammatory mediators. And the second is the retrograde flow of pancreatic enzymes from the duodenum into the pancreatic duct leading to pancreatic cell damage and autolysis. Therefore, it is to be kept in our differential, the SMA syndrome in any patient with sudden weight loss, or spinal surgery that alters aortomesenteric angle, presenting for acute abdominal pain, since management can prohibit further admissions for recurrent pain and recurrent pancreatitis with all its complications.

Consent

Consent was taken from the patient herself.

Informed consent was not obtained from the patient referenced in the case report (deceased). Multiple attempts were made to reach his next of kin to obtain consent, but we were unable to make contact with his family.

References

- Whitcomb DC (2006) Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 354(20):2142-2150.

- Glasbrenner B, Adler G (1993) Pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology 40(6): 517-521.

- Wang GJ, Gao CF, Wei D, Wang C, Ding SQ (2009) Acute pancreatitis: Etiology and common pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 15(12): 1427-1430.

- Banks PA, Freeman ML (2006) Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 101(10): 2379-400.

- Ahmed AR, Taylor I (1997) Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Postgrad Med J 73(866): 776-778.

- Welsch T, Büchler MW, Kienle P (2007) Recalling superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Dig Surg 24(3): 149-156.

- Pasumarthy LS, Ahlbrandt DE, Srour JW (2010) Abdominal pain in a 20-year-old woman. Cleve Clin J Med 77(1): 45-50.

- Lippl F, Hannig C, Weiss W, Allescher HD, Classen M, Kurjak M (2002) Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: Diagnosis and treatment from the gastroenterologist's view. J Gastroenterol 37(8): 640-643.

- Neri S, Signorelli SS, Mondati E, Pulvirenti D, Campanile E, et al. (2005) Ultrasound imaging in diagnosis of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Intern Med 257(4): 346-351.

- Barkhatov L, Tyukina N, Fretland ÅA, Røsok BI, Kazaryan AM, et al. (2017) Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: Quality of life after laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy. Clin Case Rep 6(2): 323-329.

- Watanabe T, Fujita M, Hirayama Y, Iinuma Y (2011) Superior mesenteric artery syndrome and acute pancreatitis in a boy with eating disorder: A case report. Open Journal of Pediatrics 01: 94-97.

© 2022 Mona Hallakd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)