- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Role of Statins in the Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

Priya Nair1, Raghuram Tangirala2, Anoop K Koshy3, Krishnapriya S4, Renjitha Bhaskaran5, Harshavardhan Rao B6* and Rama P Venu7

1Assistant Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Amrita Institute of Medical Science, Kochi, Kerala, India

2Resident, Department of Gastroenterology, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala, India

3Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala, India

4Healthcare Research Analyst, Department of Gastroenterology, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala, India

5Tutor, Department of Biostatistics, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala, India

6Associate Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Amrita Institute of Medical Science, Kochi, Kerala, India

7Professor and head of the department of Gastroenterology, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala, India

*Corresponding author:Harshavardhan Rao B, Department of Gastroenterology, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Ponekkara, Kochi, Kerala, India

Submission:October 04, 2021;Published: October 14, 2021

ISSN 2637-7632Volume6 Issue2

Abstract

Introduction: Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains a major cause of cancer-related mortality. Statins have been shown to exert anti-tumour effects by inducing apoptosis, inhibiting angiogenesis and preventing metastasis. The role of statins in PDAC however, is not yet established. In this study, we have studied the impact of statins on the overall survival in patients diagnosed with PDAC.

Methods: This was a prospective observational cohort study where all consecutive patients with histologic evidence of PDAC between January 2017 to December 2019 were included. Patients were classified as statin users if they had taken statins for minimum of 3 months prior to the diagnosis and continued the medication for a minimum of 30 days after the diagnosis of PDAC. Primary outcome of the study was overall survival. Stratified analysis was performed with respect to stage (metastatic vs non-metastatic) and treatment modality offered (curative resection, palliative chemotherapy, palliative biliary drainage).

Results: A total of 185 patients diagnosed with PDAC were included (mean age 62±12.06, M: F=1.6). Overall, 33/185 patients (17.8%) were found to be on statins. On multivariate analysis, statins were found to have an independent association with overall survival (HR-0.34, 95% CI 0.19- 0.78, p value 0.009). In stratified analysis, statins provided a survival benefit in metastatic disease (p value 0.05) and patients on conservative management (p value 0.04).

Conclusion: Statins were found to reduce the overall risk of mortality by 66% in patients with PDAC. The effect of statins was most evident in patients with advanced metastatic disease.

Keywords: Pancreas; Cancer; Adenocarcinoma; Statins; Survival; Atorvastatin

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a common cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. Moreover, a majority of patients (80%) are diagnosed at an advanced stage at presentation precluding surgical resection which is the mainstay of curative treatment options [1,2]. Multi-agent chemotherapy has been developed in recent years and have shown improved survival rates, even in patients with locally advanced and metastatic tumours [3,4]. In addition, adjuvant chemotherapy has also conferred a survival advantage in patients with resected pancreatic cancer [5,6]. However, despite these developments, PDAC related mortality remains high, with a 5 year survival rate of 6 7% across all stages [7,8]. This has paved the way for a growing body of evidence that explores the role of chemo-preventive medications that aim to inhibit, retard or reverse the carcinogenesis process [9]. Among the various options studied, statins have been a promising option [10-12].

Statins are a class of drugs that are primarily 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors. They are commonly used for their lipid lowering effects which in turn lead to lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary artery diseases [13,14]. In addition, statins have also been shown to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects that seem to exert an anti-neoplastic effect by inducing apoptosis, inhibiting angiogenesis and preventing tumour metastasis [14]. Anti-tumour activity is mainly mediated by HMGCoA reductase inhibition which is a rate limiting enzyme in the mevalonate/cholesterol synthesis pathway [15,16]. In addition, pre-clinical studies in K-Ras mutant mice have demonstrated delayed progression of Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PanIN) lesions to PDAC with statins [17,18]. The role of statins in the treatment of PDAC however, remains controversial. Recent observational studies and meta-analyses support the role of statin use to prevent development of PDAC [11,19]. Moreover, statins have also shown benefit in specific subgroups of patients with resectable and unresectable PDAC [20-22]. However, heterogenous patient population and inconsistent results among the observational studies limit generalizability of these findings. In addition, the dose response relationship and varying effect of the different types of statins needs more clarity. In order to further elucidate the protective role of statins with overall survival in patients with PDAC, we performed an observational cohort study at a large tertiary care referral centre. In addition, we also studied the differential effects of the type of statins and the dose-response relationship of statins with PDAC outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study participants and design

This was a single centre, prospective observational cohort study conducted in a high-volume tertiary care centre, between January 2017 to December 2019. All consecutive patients evaluated for a pancreatic mass were initially considered for the study. Tissue samples from patients diagnosed with PDAC were obtained by either Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Fine Needle Biopsy (EUS-FNB), or surgically resected specimens. Patients with malignant cystic lesions of the pancreas, intra-ductal papillary mucinous neoplasia, neuroendocrine carcinoma and other tumours of the pancreas were excluded from the study. The study was in accordance with the principles of Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

All relevant demographic data of the patient population (age at diagnosis, gender, pre-existing comorbidities like diabetes, coronary artery disease, cerebro-vascular accident, chronic liver disease, chronic pancreatitis, chronic kidney disease, lifestyle practices like smoking and alcohol), past/family history of pancreatic as well as other malignancies, PDAC diagnosis (mode of diagnosis, degree of differentiation, immune-histochemistry results), laboratory results ( complete blood counts, liver function tests, markers of inflammation: C-Reactive Protein (CRP), neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, CA19-9), tumour burden and imaging results (Tumour-Node- Metastasis (TNM) stage, local infiltration, vascular involvement, distant metastasis, lymph nodal involvement) and treatment details (surgical findings, neoadjuvant/adjuvant/palliative chemotherapy course) were recorded in pre designed proformas. Based on criteria used in the modified Glasgow prognostic score for cancers. the cut-off for CRP and albumin was taken as 10mg/L and 3.5gm/dL respectively [23]. Patients with metastatic disease were considered for chemotherapy with either modified FOLFIRINOX regimen or Gemcitabine plus nab-Paclitaxel regimen based on clinical parameters and performance status [24,25]. Patients with poor functional status were managed conservatively with palliative biliary drainage and optimal pain management. Palliative biliary drainage was achieved by the endoscopic placement of an endobiliary prosthesis (plastic biliary stent/Self Expanding Metal Stent (SEMS)) using Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiography (ERC). The 7th edition of the tumour-node-metastasis system from the American Joint Committee on Cancer was used to determine the clinical stage of the study patients [26]. In inoperable patients, clinical cancer stage was confirmed by imaging studies, including ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography.

Details of statin intake

Details regarding intake of statins included duration of statin intake prior to diagnosis of PDAC, type of statins taken and dosage of the medication used. Patients were classified as statin users if they had taken statins for minimum period of 3 months [27]. Type of statins were divided into two groups-lipophilic (such as Atorvastatin, Lovastatin and Simvastatin) or hydrophilic (such as Pravastatin, Rosuvastatin and Fluvastatin).

Outcomes of the study

Overall Survival (OS) was defined as the interval from the diagnosis date to the date of death from any cause or last follow-up [28]. Short term, intermediate term and long term mortality was taken at 3 month, 6 months and 1 year time points respectively. Disease Free Survival (DFS) was defined as length of time from when adjuvant chemotherapy for the patient following surgery ends, till the appearance of signs and symptoms of cancer recurrence which was confirmed by imaging studies (18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET-CT). Progression Free Survival (PFS) was computed for patients with inoperable cancers as length of time from the end of chemotherapy treatment course to the first appearance of signs and symptoms of cancer recurrence which was confirmed by imaging studies (PET-CT).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Categorical variables were expressed using frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were presented by mean and standard deviation. Univariate analysis was first performed to assess the association of known factors that affect overall survival. Following this multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to adjust for confounding variables in order to compute a hazard ratio with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for overall survival as well as progression free survival. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Survival probability of patients on statins and the comparison of all factors that affect survival was performed using Kaplan Meier analysis and log rank test was used to test significance. A multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to then ascertain level of significance of statins with overall survival.

Result

Characteristic of the study population

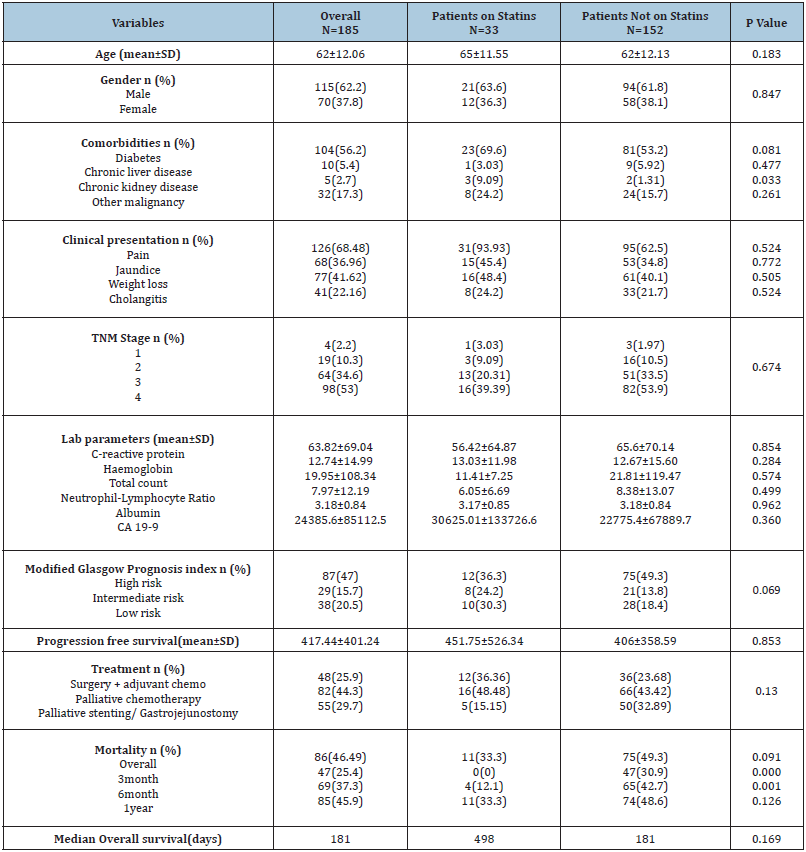

A total of 185 patients who were followed up for a minimum of 1 year were included in the study. The mean age of the population as found to be 62±12.06 years (Range 11-89 years) with a male preponderance (M: F= 1.6). A total of 104 patients (56.2%) had Diabetes mellitus, 33(17.84%) had coronary artery disease and 70(37.84%) hypertension. Chronic liver disease was found in 10 patients (5.4%) while 5 patients (2.7%) had chronic kidney disease. A total of 31 patients (16.85%) had chronic pancreatitis in the background and 32 patients (17.3%) had past history/family history of other cancers. The most common clinical presentation among the study population was pain (n=126(68.48%)), followed by weight loss (n=77(41.62%)), jaundice (n=68(36.96%)) and cholangitis (n=41(22.16%)). At the time of presentation, TNM Stage IV cancer was found in 98 patients (53%) with liver metastasis being the most common site of spread. Lymph node metastasis were seen in 40 (41.24%) while vascular involvement was noted in 37 patients (39.36%). TNM stage III was seen in 64(34.59%) patients with local infiltration to the duodenum and biliary system seen in 18 patients (29.03%). Only a minority proportion of patients presented with TNM Stage I/II disease (23(12.4%)). Curative resection which includes Whipple’s surgery or distal pancreatectomy could be performed in a total of 48 patients (25.9%). A total of 82 patients (44.3%) underwent palliative chemotherapy and 24 patients (12.97%) underwent radiotherapy. Palliative biliary drainage and conservative management was done in 55 patients (29.7%) owing to poor functional status and advanced disease. Among these patients, 40/55 patients (72.7%) underwent ERC with the placement of a biliary stent. All baseline characteristics of the population is given in Table 1.

Table 1: Mesh placement division on correcting hernias.

Details of statin use among the study population

Statins were prescribed predominantly for coronary artery disease and patients with cerebrovascular disease in this study. Statin use was noted in a total of 33 patients (17.8%). The median duration of statin consumption in the study was 20 months. The most common statin used was Atorvastatin in 42 patients (91.30%), followed by Rosuvastatin in 4 patients (8.70%). Atorvastatin was used at a dosage of 10mg in 19 patients (41.30%), while 14 patients (30.43%) were prescribed the drug at 20mg/d and 4 patients (8.70%) were on atorvastatin at 40mg/d.

There were no statistically significant differences with regard to the distribution of comorbidities between the patients who were on statins as compared to the patients without statins. Stage at diagnosis was also not statistically significant with 16 patients (39.39%) having TNM stage IV disease among patients on statins as compared to 82 patients (53.9%) who were not on statins. Earlystage cancer (TNM stage I/II) was seen in 4 patients (12.12%) in the statin group as compared to 19 patients (12.5%) who were not on statins. Curative resection with adjuvant chemotherapy was possible in 12/33 patients (36.36%) in the statin group as compared to 36 patients (23.68%) among patients not on statins. Palliative chemotherapy/radiotherapy was possible in and 16 patients (48.48%) in the statin group as compared to 66 patients (43.42%) among patients who were not on statin therapy (p value 0.13).

Outcome analysis

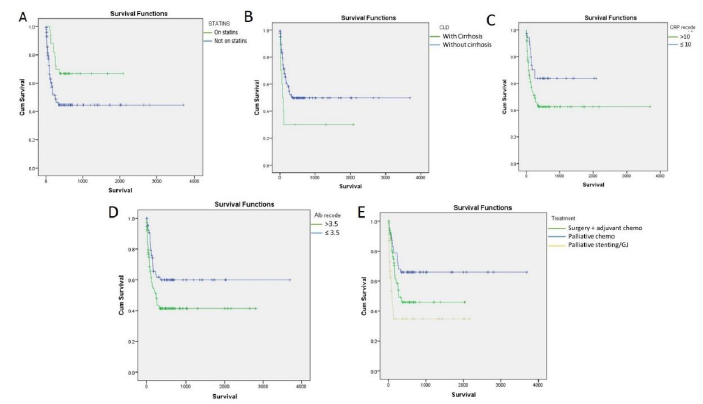

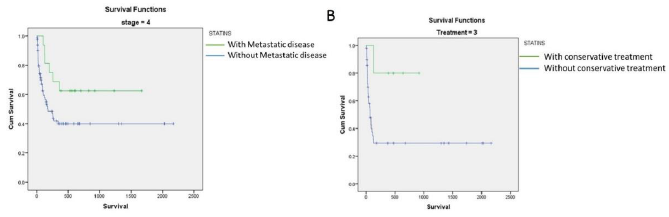

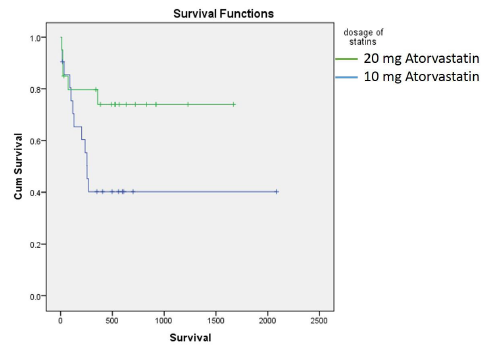

Overall mortality at 1 year in this study was 85/86 patients (98.83%). Among these patients 47 (55.29%) patients succumbed to the illness within 3 months of the diagnosis, while 69 (81.17%) patients succumbed to the illness within 6 months of diagnosis. Median Overall survival in this study was found to be 181 days. Consumption of statins was found to have significant impact on overall survival (Figure 1). On univariate analysis, apart from statin consumption, underlying chronic liver disease (p value 0.049), elevated C-reactive protein (p value 0.026), serum Albumin (p value 0.013) and curative resection with adjuvant chemotherapy (p value <0.001) were found to have a statistically significant association with overall survival (Figure 1). On multivariate analysis, only serum albumin and consumption of statins had an independent association with overall survival (p value 0.017 & 0.009 respectively). Consumption of statins was found to have a hazard ratio of 0.34 (95% CI 0.19-0.78) on overall survival of patients with PDAC in this study. Stratified analysis with respect to stage of the disease and treatment modality was performed. Statins were found to provide a significant survival benefit among patients with metastatic disease (p value 0.05 by log rank test). In addition, statins provided a significant survival benefit among patients who did not receive any chemotherapy or surgical interventions (p value 0.04 by log rank test) (Figure 2). Among patients who underwent surgical resection, there was no statistically significant difference in the DFS between patients on statins and those not on statins (410.5 vs 420.5, p value 0.936). Similarly, PFS was also not found to be different between patients on statins and those not on statins (264.8 vs 196.3, p value 0.181). Among patients on atorvastatin, a dose-response relationship was observed on overall survival, between patients who were on 10mg of the drug (359 days) as compared to patients who were on 20mg of Atorvastatin (564 days) (p value 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 1:Kaplan Meier survival analysis of all variables that have an independent association with overall survival (p value by log rank test).

A. Association of consumption of Statins with overall survival, p=0.008

B. Association of Chronic liver disease with overall survival, p=0.049

C. Association of C-reactive protein with overall survival, p=0.026

D. Association of serum albumin with overall survival, p=0.013

E. Association of treatment received with overall survival, p<0.001

Figure 2:Stratified analysis of overall population for stage of the disease and different modalities of treatment (p value by log rank test).

A. Association of statins with metastatic disease, p=0.056

B. Association of statins with conservative treatment (Palliative stenting/GJ), p=0.041

Figure 3:Kaplan Meier analysis showing a survival benefit among patients who received 20mg of Atorvastatin as compared to 10mg Atorvastatin (p value= 0.054 by log rank test).

Discussion

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a disease that causes significant morbidity and mortality [1]. Despite progress made in multimodality treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy, the mortality rate of pancreatic cancer has remained considerably high. This is largely attributable to a late diagnosis, as most patients with pancreatic cancer remain asymptomatic until the disease develops to an advanced stage [29]. Statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) are one of the most commonly used drugs used primarily for both primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events [30]. The antitumour activity of statins has been well documented in pre-clinical studies [31]. Multiple studies have shown that statins may inhibit the growth of a variety of cancer cell types, including hepatocellular cancer, renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer, medulloblastoma and glioblastoma multiforme [32-34]. Inhibition of the key enzyme of the mevalonate pathway, HMG-CoA reductase, results in the reduced production of important compounds essential for cancer cell survival, like isoprenoids, dolichol, ubiquinone, and isopentenyl adenine [35]. The role of statins in the prevention of PDAC in high risk subgroups has been documented in the past [20,22,36]. However, their impact on prognosis of patients with established diagnosis of PDAC has not been elucidated. Most studies thus far, have shown a favorable role of statins on overall prognosis, however, data has been heterogenous with respect to type of statins, duration of treatment and stage of the disease.

The results of this study clearly show that statins had an independent association with overall survival in patients with PDAC. Moreover, duration of statin therapy was also significantly associated reduced mortality. Majority of the patients in this study were treated with Atorvastatin at a dosage of 10mg/d. In the stratified analysis, the benefit of statins was best observed in patients who did not receive any chemotherapy or surgical interventions (p value 0.04). This highlights the protective role of statins in patients with advanced disease and can prove to be a useful adjunctive treatment modality in these patients. Observational studies in the past exploring the impact of statins in patients with PDAC have shown mixed results [21,37-39]. In a study by Jeon and colleagues, statin use after the diagnosis of PDAC was associated with 21% reduced risk of death (hazard ratio 0.79, 95% CI 0.67-0.93). However, analysis was restricted to early stage cancer in elderly patients with comorbidities [21]. In another study, prior simvastatin use was shown to be associated with higher overall survival (28.5 vs 16.5 months) [14]. However, duration and dosage of statins after the diagnosis of PDAC was not assessed and is essential to establish anti-tumour effects of the drug. There have been multiple metanalyses performed which have shown a beneficial effect of statins in the treatment of PDAC [12,34]. However, there is marked heterogeneity with the type of statins used, dosage and duration of consumption and stage of disease which can have profound impact on overall outcome in these patients. When the results of this study were stratified according to the stage of the disease, statins were found to have a significant impact on overall survival in patients in metastatic PDAC as compared to those with early/locally advanced disease. In addition, inoperable tumours who did not receive even palliative chemotherapy were also benefitted by the consumption on statins. There are a few limitations of the present study. The relatively small number of patients who were on statins in this study could limit generalizations based on the study findings. However, despite this sample, the findings of the study have provided valuable data on the effect of statins especially, atorvastatin, on the overall survival in patients with PDAC. Another important limitation would be the heterogeneity of dosage of statins seen in this study. Some studies have studied cumulative dosage of statins and its effect on overall survival [14]. Interventional trials using fixed dosage of statins are warranted to assess the dose-response relationship of the anti-tumour activity of these drugs. Lastly, there may be a bias among the two groups owing to the possibility that statin users may inherently be more concerned about their health which may be reflected in their lifestyle practices. However, this alone would not be sufficient to explain the 66% risk reduction. In addition, patients who were on statins had more comorbidities which are known to have a deleterious effect on overall survival. The findings of this study showing a survival advantage despite these differences indicates that statins may have an important role in risk reduction in these patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Statins (especially atorvastatin) were found to reduce the risk of mortality by 66% (HR 0.34, 95% CI 0.19 - 0.78) in patients with PDAC. This association was maintained in multivariate analysis after adjusting for all confounding factors. The effect of statins was most evident in patients with metastatic disease and in those who were managed conservatively with no chemotherapy/ surgical interventions. A dose-response relationship was observed among patients on Atorvastatin and is an important aspect that needs further validation. Future interventional trials with predesigned type and dosage of statins in patients with PDAC are warranted to establish their efficacy in specified treatment groups.

Strobe Statement

Strobe Statement have been adopted.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala.

Informed Consent Statement

All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-Interest Statement

The authors of this manuscript having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Sharing Statement

There is no additional data available.

Funding

No funding obtained.

References

- Simoes PK, Olson SH, Saldia A, Kurtz RC (2017) Epidemiology of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Chinese Clin Oncol 6(3): 24.

- Spanknebel K, Conlon KCP (2001) Advances in the surgical management of pancreatic cancer. Cancer J 7(4): 312-323.

- Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N (2014) Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 371(11): 1039-1049.

- Gong J, Sachdev E, Robbins LA, Lin E, Hendifar AE, et al. (2010) Statins and pancreatic cancer. Oncol Lett 13(3): 1035-1040.

- Hidalgo M (2010) Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 362(17): 1605-1617.

- Wolfgang CL, Herman JM, Laheru DA, Klein AP, Erdek MA, et al. (2013) Recent progress in pancreatic cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 63(5): 318-348.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013) Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 63(1): 11-30.

- Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, et al. (2014) Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res 74(11): 2913-2921.

- Signoretti M, Bruno MJ, Zerboni G, Poley JW, Delle Fave G, et al. (2018) Results of surveillance in individuals at high-risk of pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur Gastroenterol J 6(4): 489-499.

- Choi JH, Lee SH, Huh G, Chun JW, You MS, et al. (2019) The association between use of statin or aspirin and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A nested case-control study in a Korean nationwide cohort. Cancer Med 8(17): 7419-7430.

- Archibugi L, Arcidiacono PG, Capurso G (2019) Statin use is associated to a reduced risk of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 51(1): 28-37.

- Tamburrino D, Crippa S, Partelli S, Archibugi L, Arcidiacono PG, et al. (2020) Statin use improves survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 52(4):392-399.

- Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore THM, Burke M, et al. (2013) Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane database Syst Rev (1): CD004816.

- Lee HS, Lee SH, Lee HJ, Chung MJ, Park JY, et al. (2016) Statin use and its impact on survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Med 95(19): 1-7.

- Sumi S, Beauchamp RD, Townsend CMJ, Uchida T, Murakami M, et al. (1992) Inhibition of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell growth by lovastatin. Gastroenterology 103(3): 982-989.

- Ura H, Obara T, Nishino N, Tanno S, Okamura K, et al. (1994) Cytotoxicity of simvastatin to pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells containing mutant ras gene. Jpn J Cancer Res 85(6): 633-638.

- Fendrich V, Sparn M, Lauth M, Knoop R, Plassmeier L, et al. (2013) Simvastatin delay progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer formation in a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol 13(5): 502-507.

- Mohammed A, Qian L, Janakiram NB, Lightfoot S, Steele VE, et al. (2012) Atorvastatin delays progression of pancreatic lesions to carcinoma by regulating PI3/AKT signaling in p48Cre/+ LSL-KrasG12D/+ mice. Int J cancer 131(8): 1951-1962.

- Gronich N, Rennert G (2013) Beyond aspirin-cancer prevention with statins, metformin and bisphosphonates. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 10(11): 625-642.

- Wu BU, Chang J, Jeon CY, Pandol SJ, Huang B, et al. (2015) Impact of statin use on survival in patients undergoing resection for early-stage pancreatic cancer. Am J Coll Gastroenterol 110(8): 1233-1239.

- Jeon CY, Pandol SJ, Wu B, Cook-Wiens G, Gottlieb RA, et al. (2015) The association of statin use after cancer diagnosis with survival in pancreatic cancer patients: A seer-medicare analysis. PLoS One 10(4): e0121783.

- E JY, Lu SE, Lin Y, Graber JM, Rotter D, et al. (2017) Differential and joint effects of metformin and statins on overall survival of elderly patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A large population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26(8): 1225-1232.

- Imaoka H, Mizuno N, Hara K, Hijioka S, Tajika M, et al. (2016) Evaluation of modified glasgow prognostic score for Pancreatic cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Pancreas 45(2): 211-217.

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, et al. (2011) FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 364(19): 1817-1825.

- Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, et al. (2013) Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 369(18): 1691-703.

- Edge SB, Compton CC (2010) The American joint committee on cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 17(6): 1471-1474.

- Dincer I, Ongun A, Turhan S, Ozdol C, Kumbasar D, et al. (2006) Association between the dosage and duration of statin treatment with coronary collateral development. Coron Artery Dis 17(6): 561-5.

- Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Behrman SW, Benson AB 3rd, Casper ES, et al. (2014) Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 2.2014: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 12(8): 1083-1093.

- Kamisawa T, Wood LD, Itoi T, Takaori K (2016) Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 88(10039): 73-85.

- Abraham SC, Klimstra DS, Wilentz RE, Yeo CJ, Conlon K, et al. (2002) Solid-pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas are genetically distinct from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and almost always harbor beta-catenin mutations. Am J Pathol 160(4): 1361-1369.

- McGregor GH, Campbell AD, Fey SK, Tumanov S, Sumpton D, et al. (2020) Targeting the metabolic response to statin-mediated oxidative stress produces a synergistic antitumor response. Cancer Res 80(2): 175-188.

- Wong WWL, Dimitroulakos J, Minden MD, Penn LZ (2002) HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the malignant cell: The statin family of drugs as triggers of tumor-specific apoptosis. Leukemia 16(4): 508-519.

- Paragh G, Kertai P, Kovacs P, Paragh GJ, Fülöp P, et al (2003) HMG CoA reductase inhibitor fluvastatin arrests the development of implanted hepatocarcinoma in rats. Anticancer Res 23(5A): 3949-3954.

- Wang D, Rodriguez EA, Barkin JS, Donath EM, Pakravan AS (2019) Statin use shows increased overall survival in patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. Pancreas 48(4): E22-33.

- Bigelsen S (2018) Evidence-based complementary treatment of pancreatic cancer: A review of adjunct therapies including paricalcitol, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous vitamin C, statins, metformin, curcumin, and aspirin. Cancer Manag Res 10: 2003-2018.

- Moon DC, Lee HS, Lee Y Il, Chung MJ, Park JY, et al. (2016) Concomitant statin use has a favorable effect on gemcitabine-erlotinib combination chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer. Yonsei Med J 57(5): 1124-1130.

- Cui X, Xie Y, Chen M, Li J, Liao X, et al. (2012) Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 23(7): 1099-1111.

- Chiu HF, Chang CC, Ho SC, Wu TN, Yang CY (2011) Statin use and the risk of pancreatic cancer: A population-based case-control study. Pancreas 40(5): 669-672.

- Walker EJ, Ko AH, Holly EA, Bracci PM (2015) Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: Results from a large, clinic-based case-control study. Cancer 121(8): 1287-1294.

© 2021 Harshavardhan Rao B. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)