- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Factors Associated with the Occurrence of Metastatic Dissemination in Rectal Cancer

Ana Lazarova*

Department of Radiology, Medical faculty, University Clinic for surgery disease St. NaumOhridski, Macedonia

*Corresponding author: Ana Lazarova, Department of Radiology, St.Kiril and Methodius, Medical faculty, University Clinic for surgery disease St.Naum Ohridski,Macedonia

Submission: December 21, 2020;Published: January 25, 2021

ISSN 2637-7632Volume5 Issue3

Abstract

Introduction: The occurrence of metastases in rectal cancer disease is an additional important worrying factor not only in the patient but also in the surgeon due to their often fatal outcome. Up to 20% of patients with rectal cancer have metastatic disease at the stage of detection of the primary disease. Despite the development of preoperative neoadjuvant treatment, preoperative chemo-radiotherapy in rectal cancer, metastases pose a challenge in the proper management of the disease, especially as they significantly reduce the 5-year survival rate.

Aim of the study: The aim of this study is to highlight the significant factors that have influence in the occurrence of metastatic disseminated disease in the patients with primary diagnosed rectal cancer.

Material and Methods: This is a prospective study which include a 82 patients aged from 43 to 87 years, with an average age of 66 years with previously colonoscopy proven rectal cancer. Before the operation magnetic resonance images (MRI) was made at-1.5T magnet for determination the MRI T and N staging preoperatively. For detection of distant metastatic deposits, M staging, computer tomography (CT) after dynamic application of intra venous contrast medium on lungs and whole abdomen was done in all 82 patients.

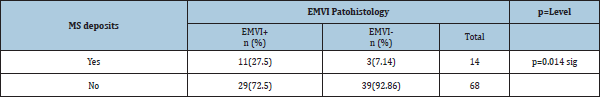

Results: Metastatic deposits were found in 14 (17.07%) of 82 patients with rectal cancer disease, of them 12 were male and 2 patients were female. Eleven of the patients had metastatic deposits in the liver, 2 patients had metastatic deposits in the lung and liver at the same time and 1 patient had metastatic deposit in the peritoneum. The occurrence of metastases was significantly associated with pathohistological findings of extra mural vascular invasion EMVI (p=0.014). Metastases were detected in 78.6% (11) EMVIpositive patients and 21.4% (3) EMVI-negative patients. In the group of patients without metastases, 42.65% (29) patients were EMVI positive, 57.35% (39) were EMVI negative. Metastases were detected in one patient with T2 stage of rectal cancer, 18.2% (10) of T3 stage, most commonly and within T4 stage of rectal cancer-25% (3) patients. According to the N stage of rectal cancer metastasis were found in 3 patients N0 stage, 5 patients in N1 and also 5 in N2 and 1 patient in N3 stage of the disease. Depending on the localization of the rectal cancer in 4 patients rectal cancer was localized in the rectosigmoid part, in 4 patients in the proximal part of the rectum, in 2 patients with metastasis, rectal cancer was localized in the mid rectum and in 4 patients rectal cancer was in distal part of the rectum.

Conclusion: Rectal cancer is spread malignant disease worldwide and it is third common malignancy after breast and lung cancer in woman and prostatic and lung cancer in male population. Occurrence of metastatic dissemination when primary rectal cancer has been diagnosed is not so rare condition but is very important to be aware of the factors that are associated with metastatic dissemination of rectal cancer. Knowing the possibility of dissemination can lead to increase the 5 years survival rate and decrease the percentage of incurability.

Keywords: Rectal cancer;Metastatic dissemination;Computer tomography

Introduction

Despite the development of preoperative neoadjuvant treatment, preoperative chemoradiotherapy

in rectal cancer, metastases pose a challenge in the proper management of the

disease, especially as they significantly reduce the 5-years survival rate [1,2]. The occurrence

of metastases in rectal cancer disease is an additional important worrying factor not only in

the patient but also in the surgeon due to their often-fatal outcome. The fact that up to 20%

of patients with rectal cancer have metastatic disease at the stage of detection of the primary

disease is challenging and should be taken with great concern [3,4].

The latest research on the spread of metastases focuses on their development at the

cellular and molecular level. Unfortunately, the epidemiological knowledge is still insufficient

due to the fact that the registers for cancerous diseases do not always include the data for the metastatic disease [5]. The “anatomical/mechanical hypothesis”

and the “seed and soil” hypothesis are widely accepted to explain

the spread of metastases. Recently, the “seed and soil” hypothesis

has been specially developed because it examines the tumor-the

stromal reaction at the molecular level. Specific tumor cells show

a predisposition to certain target organs. Dissemination of initial

metastases acts as a seed for further metastatic scattering [2,6].

Blood drains from the proximal rectum and rectosigmoid colon

through the portal system to the liver. The next organs from the liver

are the lungs through the heart. All parts of the gastrointestinal tract

share a common lymphatic drainage-through the cistern to the left

subclavian vein-to the lungs. Additionally, metastases may spread

through the peritoneal fluid into the peritoneal cavity [7,8]. Mucinous

adenocarcinomas show a predisposition to the peritoneum and are

more aggressive; mucinous adenocarcinomas are also thought to be

genetically predisposed to the peritoneal space [9,10]. Due to the

embryological origin of the proximal and distal rectum it is clear

that they demonstrate a different biology in terms of metastases

[11,12]. Anatomical localization and histological subtypes have a

strong reflection on the manner of metastasis, especially when it

comes to an organ other than the liver. Rectal cancer can metastasize

to the liver, lungs, central nervous system (CNS), peritoneum, and

bones. The prognosis for survival approximately is worst in CNS

metastasis-4 months, bones-6 months, liver metastases - 9 months,

and lung metastases-14 months [13-15].

Material and Methods

This is a prospective study which includes a 82 patients aged from 43 to 87 years, with an average age of 66 years with previously colonoscopy proven rectal cancer. Before the operation magnetic resonance images (MRI) were made at-1.5T magnet for determination the MRI T and N staging preoperatively. For detection of distant metastatic deposits-M staging, computer tomography (CT) after dynamic application of intra venous contrast medium on lungs and whole abdomen was done in all 82 patients.

Results

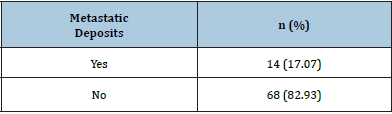

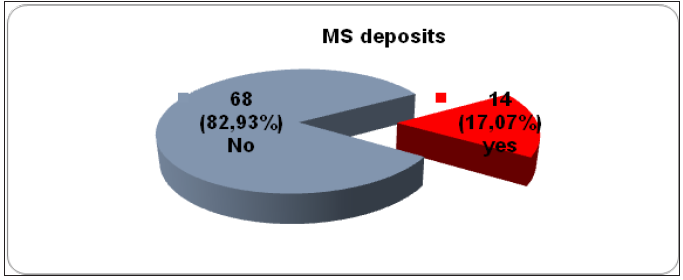

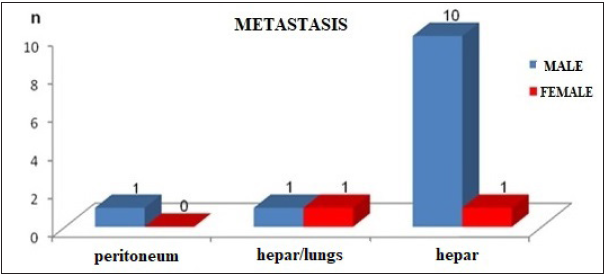

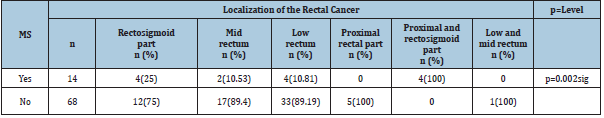

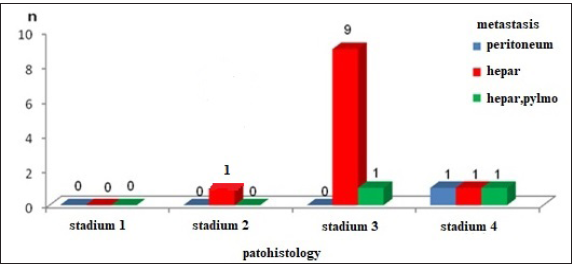

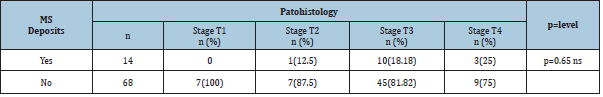

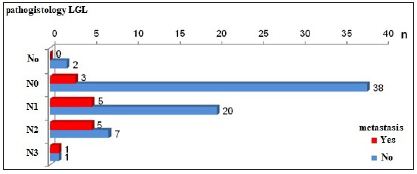

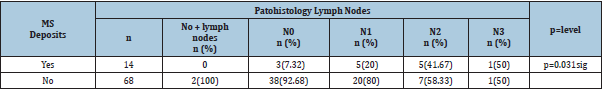

Fourteen (17.07%) of the patients have metastatic dissemination when primary was diagnosed with rectal cancer disease (Table 1; Figure 1). Ten of male patients have metastatic deposits in the liver, one in liver and lungs and one male patient has metastatic deposits in peritoneum. One female patient has metastatic deposits in the liver and one in both liver and lungs (Figure 2). Patients with and without metastases had a similar mean age on average, about 67 years, and no statistically significant difference (66.85±9.1 vs. 66.62±10.01) (Table 2) The occurrence of metastases was significantly associated with pathohistological findings of extra mural vascular invasion (p=0.014). Metastases were detected in 78.6% (11) EMVI-positive patients and 21.4% (3) EMVI-negative patients. In the group of patients without metastases, 42.65% (29) patients were EMVI positive, 57.35% (39) were EMVI negative (Table 3; Figure 3). Depending on the localization of the rectal cancer in 4 patients rectal cancer was localized in the rectosigmoid part, in 4 patients in the proximal part of the rectum, in 2 patients with metastasis rectal cancer was localized in the mid rectum and in 4 patients rectal cancer was in distal part of the rectum (Table 4; Figure 4). Metastases were detected in one patient with T2 stage of rectal cancer, 18.2% (10) of T3 stage, most commonly within T4 stage of rectal cancer-25% (3) patients (Table 5; Figure 5). According to the N stage of rectal cancer metastasis were found in 3 patients N0 stage, 5 patients in N1 and also 5 in N2 and 1 patient in N3 stage of the disease (Table 6; Figure 6).

Table 1:Distribution of the patients according the presents of Metastatic deposits (MS deposits).

Figure 1: Graphic presentation of metastasis dissemination in patients.

Figure 2: Graphic presentation of localization of metastasis according to patient’s gender.

Table 2:Patients age with and without metastatic deposits.

Student t=0.076, p=0.94.

Figure 3: Graphic presentation of metastatic dissemination in ЕМVI+ and ЕМVI- status in rectal cancer.

Table 3:Status of extra mural vascular invasion (EMVI) in patients with rectal cancer with and without presents of distant metastasis.

Chi-square=5.99, df=1, p=0.014.

Figure 4:Graphic presentation of localization of the rectal cancer with and without MS deposits.

Table 4:Localization of the rectal cancer with and without MS deposits.

Fisher exact test, two tailed, p=0.002.

Figure 5: Graphic presentations of the presents of MS deposits according to the T stage of rectal cancer.

Table 5:Presents of MS deposits according to the T stage of rectal cancer.

Fisher exact test, two tailed, p=0.649.

Figure 6: Graphic presentation of rectal cancer with and without MS deposits according to N stage.

Table 6: Rectal cancer with and without MS deposits according to N stages.

Fisher exact test, two tailed, p=0.031.

Discussion

Тhe presence of metastatic disseminated disease in the case

of a diagnosis of rectal cancer is an advanced stage of the disease.

That is why metastatic disseminated disease in the case of primary

rectal cancer is a challenge in treatment that requires a special

and comprehensive approach. Regardless of the progress of the

preoperative neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy approach, dealing

with distant metastases is still an important factor influencing

rectal cancer to be an incurable disease. Circulating tumor cells

are cells from the primary tumor that are found in the blood of

patients without the presence of metastases. The presence of

circulating tumor cells is a prognostic biomarker in patients with

rectal cancer [16]. Different parts of the rectum have different

blood supply. Three main arteries supply blood to the rectum. The

upper rectal artery which is a branch of the a. mesenterica inferior

supplies blood to the upper part of the rectum. The middle rectal

artery which originating from the anterior branch of the a. iliaca

interna or from the lower visceral arteries supplies the middle part

of the rectum. The inferior rectal artery originates from the internal

pudendal artery and supplies the low rectum [17]. Because the

blood supply to the rectum is through different arteries, circulating

cancer cells depend on the location of the tumor [18]. Differences

in locally advanced disease, such as the depth of tumor invasion,

the presence of lymph node metastases, and incomplete tumor

resection, correlate directly with tumor cells in the central venous

blood compartment rather than in the mesenteric venous blood

compartment [19]. Hepatic venous metastases are much more

common than those in the peripheral venous compartments [20].

For rectal carcinoma localized to the proximal end of the

middle rectum as well as the upper rectum, it is important to

determine the distance to the peritoneal reflection because the

rectum from 6cm to 8cm of the anal verge to the proximal part is

covered with peritoneum on its anterior and lateral surface [21].

Involvement of the peritoneum is very important in the further

possible spread of intraperitoneal metastases [22]. In the lower

parts of the rectum, mesorectal fat surrounds the rectum, and it

is circumferentially surrounded by a mesorectal fascia. While in

the higher parts the peritoneum covers the anterior part of the

mesorectal fat to a point called the anterior peritoneal reflection.

From the anterior peritoneal reflection, the peritoneum extends

posteriorly and bypasses the rectosigmoid junction. Peritoneal

reflection is presented as a thin (0.5mm-1mm) low signal line in

the T2 waited images that bind the anterior aspect of the rectum.

On sagittal projection, peritoneal reflection can be visualized above

the seminal vesicles in a man and at the utero-cervical angle in a

woman. The relationship of the tumor with the peritoneal reflection

should be carefully analyzed [23,24].

Mucinous rectal adenocarcinomas have a higher tendency to

metastasis and are usually more advanced at the time of diagnosis.

Of great importance is the fact whether the tumor penetrates

the sacral fascia. With standard total mesorectal excision these

lymph nodes cannot be removed [25]. Detection of malignant

extramesorectal lymph nodes indicates the need for a more extensive surgical approach, as well as the use of radiotherapy in

high-risk areas. Extramural vascular invasion (EMVI) is suspected

when the veins near the tumor are irregular or dilated. EMVI was

accepted as an independent prognostic indicator in rectal cancer

associated with a higher incidence of metastases, local recurrences,

a poorer response to preoperative chemo-radiotherapy, and,

above all, a lower survival rate [26]. It has recently been

shown that the rate of distant MS deposits and the response to

preoperative chemo-radiotherapy are strongly correlated with

the size of the blood vessels involved [27]. Metastatic deposits

in this study were detected in 17.1% (14) patients, of whom 11

had liver metastases, 2 patients had liver and lung metastases,

and one patient had peritoneum. In this group of patients with

rectal cancer, a statistically significant difference was confirmed

between male and female patients depending on the occurrence

of metastases (p=0.02). There are significant differences between

male and female responders with metastatic dissemination, more

often metastasis is present in male respondents-25% (12) versus

5.9% (2) female responders. The occurrence of metastases was

significantly associated with pathohistological findings of extra

mural vascular invasion (p=0.014). Metastases were detected in

78.6% (11) EMVI-positive patients and 21.4% (3) EMVI-negative

patients. In the group of patients without metastases, 42.65% (29)

patients were EMVI positive, 57.35% (39) were EMVI negative.

All this is a confirmation of the results of the world literature on

the importance of extramural invasion in the overall pathology

of rectal cancer. Patients with and without metastases had a

similar average age, about 67 years, so there is not statistically

significant difference (66.85±9.1 vs. 66.62 ±10.01). The occurrence

of metastases significantly depended on the localization of rectal

cancer (p=0.002). Metastases were detected in all 4 patients with

localized rectosigmoid carcinoma of the colon and upper rectum, in

25% (4) patients with rectosigmoid carcinoma, 10.5% (2) patients

with middle rectal cancer, and in 10.8% (4) patients in whom the

localization of the cancer was at the level of the lower rectum. This

is due to the embryological origin of the proximal and distal rectum

and the blood drainage through the portal bloodstream of the

rectosigmoid and proximal rectum.

Conclusion

Rectal cancer is spread malignant disease worldwide and it is third common malignancy after breast and lung cancer in woman and prostatic and lung cancer in male population. Occurrence of metastatic dissemination when primary rectal cancer has been diagnosed is not so rare condition but is very important to be aware of the factors that are associated with metastatic dissemination of rectal cancer. Knowing the possibility of dissemination can lead to increase the 5 years survival rate and decrease the percentage of incurability.

References

- Langley RR, Fidler IJ (2011) The seed and soil hypothesis revisited-the role of tumor-stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. Int J Cancer 128(11): 2527-2535.

- Fidler I (2003) The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 3(6): 453-458.

- Riihimaki M, Hemminki A, Fallah M, Thomsen H, Sundquist K, et al. (2014) Metastatic sites and survival in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 86(1): 78-84.

- Grimminger PP, Brabender J, Warnecke-Eberz U, Narumiya K, Wandhöfer C, et al. (2010) XRCC1 gene polymorphism for prediction of response and prognosis in the multimodality therapy of patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Journal of Surgical Research 164(1): e61-e66.

- Vineis P, Brennan P, Canzian F, John PAI, Giuseppe M, et al. (2008) Expectations and challenges stemming from genome-wide association studies. Mutagenesis 23(6): 439-444.

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, et al. (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61(2): 69-90.

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E (2010) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 60(5): 277-300.

- Cedermark B, Dahlberg M, Glimelius B, Påhlman L, Rutqvist LE (1997) Improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 336(14): 980-987.

- Sauer R, Fietkau R, Wittekind C, Rödel C, Martus P, et al. (2003) Adjuvant vs. neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: The german trial CAO/ARO/AIO-94. Colorectal Dis 5(5): 406-415.

- Hodgman CG, MacCarty RL, Wolff BG, May GR, Berquist TH, et al. (1986) Preoperative staging of rectal carcinoma by computed tomography and 0.15T magnetic resonance imaging. Preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum 29(7): 446-450.

- Schnall MD, Furth EE, Rosato EF, Kressel HY (1994) Rectal tumor stage: correlation of endorectal MR imaging and pathologic findings. Radiology 190(3): 709-714.

- Freedman LS, Macaskill P, Smith AN (1984) Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for operable rectal cancer. Lancet 2(8405): 733-736.

- Smith NJ, Barbachano Y, Norman AR, Swift RI, Abulafi AM, et al. (2008) Prognostic significance of magnetic resonance imaging-detected extramural vascular invasion in rectal cancer. Br J Surg 95(2): 229-236.

- Al-Sukhni E, Milot L, Fruitman M, Joseph Beyene, Charles Victor J, et al. (2012) Diagnostic accuracy of MRI for assessment of T category, lymph node metastases, and circumferential resection margin involvement in patients with rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 19(7): 2212-2223.

- Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL, Vliegen RF, Kessels AG, Van Boven H, et al. (2001) Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in prediction of tumour-free resection margin in rectal cancer surgery. Lancet 357(9255): 497-504.

- Mercury Study Group (2006) Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ 333(7572): 779.

- Tang R, Wang JY, Chen JS, Chang-Chien CR, Tang S, et al. (1995) Survival impact of lymph node metastasis in TNM stage III carcinoma of the colon and rectum. J Am Coll Surg 180(6): 705-712.

- Shepherd NA, Baxter KJ, Love SB (1995) Influence of local peritoneal involvement on pelvic recurrence and prognosis in rectal cancer. J Clin Pathol 48(9): 849-855.

- Vliegen RF, Beets G, Von Meyenfeldt MF, Alfons GH, Etienne E, et al. (2005) Rectal cancer: MR imaging in local staging-is gadolinium-based contrast material helpful? Radiology 234(1): 179-188.

- Harrison JC, Dean PJ, El Zeky F, Vander ZR (1994) From dukes through jass: Pathological prognostic indicators in rectal cancer. Hum Pathol 25(5): 498-505.

- Wolmark N, Fisher B, Wieand HS (1986) The prognostic value of the modifications of the Dukes’ C class of colorectal cancer. An analysis of the NSABP clinical trials. Ann Surg 203(2): 115-122.

- Maier A, Fuchsjager M (2003) Preoperative staging of rectal cancer. Eur J Radiol 47(2): 89-97.

- Sunderland D (1949) The significance of vein invasion by cancer of the rectum and sigmoid: a microscopic study of 210 cases. Cancer 2(3): 429-437.

- Horn A, Dahl O, Morild I (1990) The role of venous and neural invasion on survival in rectal adenocarcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 33(7): 598-601.

- Matsuoka H, Nakamura A, Sugiyama M, Hachiya J, Atomi Y, et al. (2004) MRI diagnosis of mesorectal lymph node metastasis in patients with rectal carcinoma. What is the optimal criterion? Anticancer Res 24(6): 4097-4101.

- Wanebo HJ, Koness RJ, Vezeridis MP, Cohen SI, Wrobleski DE (1994) Pelvic resection of recurrent rectal cancer. Ann Surg 220(4): 586-597.

- Mirnezami AH, Sagar PM, Kavanagh D, Witherspoon P, Lee P, et al. (2010) Clinical algorithms for the surgical management of locally recurrent rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 53(9): 1248-1257.

© 2021 Ana Lazarova. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)