- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (LAMN)-Case Report

Konrad Lewandowski1, Martyna Szczubełek1, Magdalena Kaniewska1, Małgorzata Kołos2, Piotr Kotarski3, Katarzyna Sklinda3,4, Anna Nasierowska- Guttmejer2, Grażyna Rydzewska1,5*

1Clinical Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Subunit, Central Clinical Hospital of Ministry of Interior and Administration in Warsaw, Poland

2 Department of Pathomorphology, Central Clinical Hospital of Ministry of Interior and Administration in Warsaw, Poland

3Department of Radiology, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland

4Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland

5Collegium Medicum of Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, Poland

*Corresponding author: Grażyna Rydzewska, Clinical Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Subunit, Central Clinical Hospital of Ministry of Interior and Administration in Warsaw, Poland

Submission: October 13, 2020;Published: November 30, 2020

ISSN 2637-7632Volume5 Issue2

Abstract

Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) is a rare malignancy with only 250 cases described worldwide. Uncharacteristic symptoms can cause diagnostic problems. A case of a 39-year-old man who was admitted to the hospital because of abdominal pain and non-specific USG findings, with a further diagnosis of LAMN, is described.

Keywords: Appendix;Carcinoma; Cancer; Mucinous; Treatment

Introduction

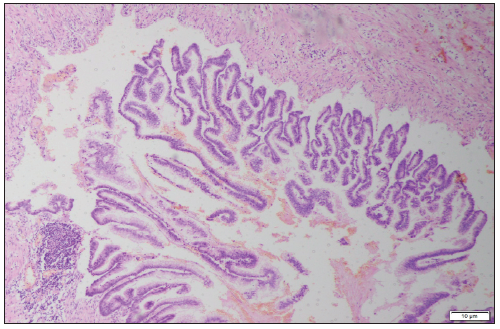

Figure 1: Magnification 4X. H&E stain. Appendiceal wall with the villous proliferation of mucinous epithelial cells.

Excluding skin cancer, colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer diagnosed in both men and women (1.8 million cases) causing almost 900000 deaths every year. Approximately 60% of cases occur in high-income countries. Since 1980 in Poland there was a 4-fold increase in the prevalence of colorectal cancer in men and 3-fold increase in women (Figure 1). 94% of all people affected are at the age of 50 and more, while 75%-over 60. Despite the widespread colonoscopy availability, death rate has remained high in recent years-in Poland in 2010 11 000 deaths registered (6000 in men and 4800 in women) [1]. 0.5% of all gastrointestinal tumors are malignant tumors of the appendix [2]. Primary cancers of the appendix are rare, with an incidence of 0.12/1 million inhabitants/year [3]. According to study performed by Collins, in histopathological examination of 50000 vermicular appendixes, adenocarcinomas were found in 41 specimens [4]. In retrospective clinicopathological analysis by Machado et al. adenocarcinomas were diagnosed in 2 out of 1646 vermicular appendixes. The first adenocarcinoma of the appendix was described in 1882 by Berger [5]. Since that moment in literature there were 250 cases described worldwide [6,7]. Usual onset of the disease is 40-80 years of age [8]. It is usually diagnosed incidentally at histologic assessment of the surgical specimen collected during appendectomy due to appendicitis (Figure 2).

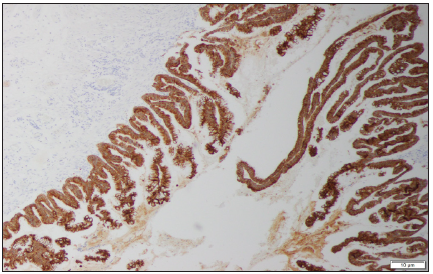

Figure 2: Magnification 10X. CK20 stain. Strong cytoplasmic positivity for intestinal type of appendiceal epithelium.

Following histopathological types of malignant tumors of the appendix can be distinguished:

1. Colonic-type adenocarcinoma 2. Mucinous adenocarcinoma 3. Goblet cell adenocarcinoma 4. Neuroendocrine carcinoma (carcinoid) [9].

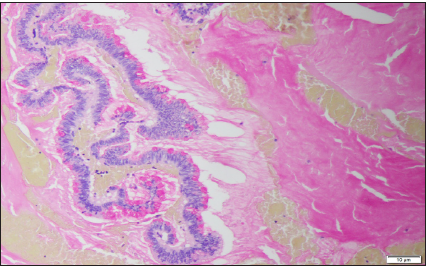

65% of malignant appendiceal tumors are of neuroendocrine origin [3]. Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) in 2012 developed a consensus classification of appendiceal mucinous lesions. According to their statement mucinous lesions of appendix may be non-neoplastic (simple mucoceles, retention cysts) or neoplastic (serrated polyps, low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm-LAMNs, high-grade mucinous neoplasms-HAMNs, mucinous adenocarcinomas) [10]. LAMN describes a neoplasm with dysplastic epithelium producing abundant mucin (Figure 3). By definition LAMN is not invasive, but its expansive growth may cause loss of muscular layers of the wall, appendix rupture and eventually spillage of cellular and acellular mucin into peritoneum [10]. Syndrome of progressive intraperitoneal accumulation of mucinous ascites related to a mucin-producing neoplasm is called pseudomyxoma peritonei. The mucinous deposits follow routes of normal peritoneal fluid flow, spreading along pelvis, paracolic gutters, liver capsule and momentum [11].

Figure 3: Magnification 10X. Mucicarmine stain. Pools of mucin in the appendiceal lumen. Abundant apical mucin with elongated nuclei and low grade nuclear atypia.

Case Presentation

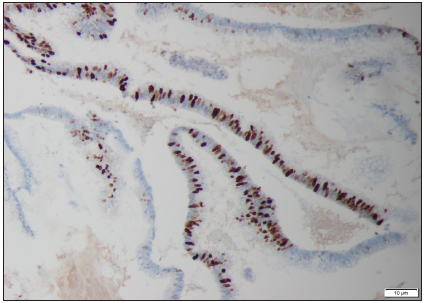

Figure 4: Magnification 10X. Ki-67 stain. Nuclear positivity in the epithelial cells of the appendix with higher proliferative index.

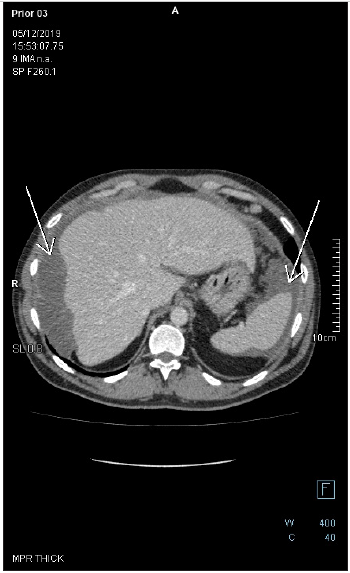

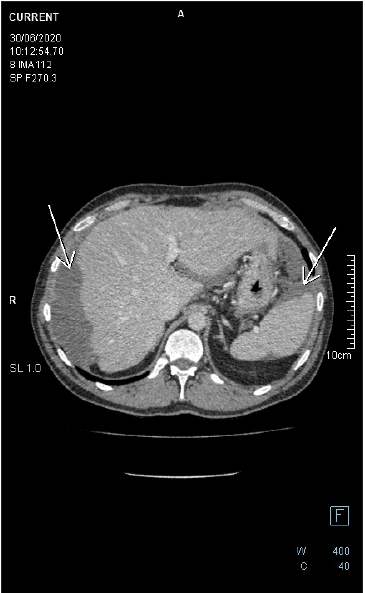

39-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for further diagnostics of pancreatic lesion (pancreatic infiltration of unclear etiology) described in outpatient USG. In medical history: in 2014 right hemicolectomy with multi-chambered mucous cyst removal (diagnosed as embryonic lesion) and appendectomy due to acute appendicitis. In colonoscopy performed in 2017 because of abdominal pain, no abnormalities were found (Figure 4). On the day of admission to the hospital patient’s general condition was fair. He complained about recurrent, twitching pain located in epigastrium and reported 3-5 bowel movements per day, without pathological admixtures. On physical examination no significant abnormalities were found. In laboratory tests we observed mild normocytic anemia Hgb 13.6g/dL, elevated concentration of Ca19-9 327IU/ml and normal IgG4 level. In abdominal ultrasound in the projection of pancreas-a heterogenous area that may correspond to an enlarged organ or an infiltration with a fluid envelope around was described. During hospitalization, CT scan of abdominal cavity was performed, which showed massive infiltrates in the peritoneum, mainly in its anterior part, around liver and spleen, as well as between intestinal loops with pelvic fluid reservoirs. Based on imaging examination, a suspicion of peritoneal pseudomyxoma or neoplastic cystic lesions was made. Due to the unclear nature of the clinical picture and imaging results described above, we have decided to reconsult the histopathological specimens collected during hemicolectomy in 2014. They were reexamined by the Head of the Pathological Department, who diagnosed low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN). The patient was referred to the Department of Surgery, where omentectomy and release of adhesions were performed. Afterwards chemotherapy in the FOLFOX-6 scheme was started (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Axial-CECT of the upper abdomen reveals perihepatic and perisplenic mucinous deposits. There is a faint soft tissue circumferential component in the perihepatic lesion, the wall of which is enhancing with no appreciable septation nor calcification. There is no fat stranding in the adjacent fat tissue.

Histopathology

The study was performed using archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. The sections of 4um thickness were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Specimens were reexamined by the Head of the Pathological Department of Clinical Hospital of Ministry of the Interior and Administration in Warsaw. The histological type and the tumor grade were based on the WHO Classification (Tumours of the Digestive System, Tumours of the appendix, 4th edition, Lyon). TNM staging was based upon the 8th edition of AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 2017). Afterwards, standard-size sections were dewaxed, rehydrated and blocked for endogenous peroxidase. Immunohistochemical tests were prepared by fully automated Ventana Benchmark GX instrument and following antibodies were used: CK20, CK7, CDX2, P53, Ki-67. Selected slides were evaluated for mucin with mucicarmine stain as well.

Figure 6: Follow up axial-CECT of the upper abdomen reveals perihepatic and perisplenic mucinous deposits. There is a faint soft tissue component in the perihepatic lesion, the wall of which is enhancing with no appreciable septation nor calcification. There is no fat stranding in the adjacent fat tissue. Lesions are noticed to be stable on CECTs performed in years 2019 and 2020.

Microscopic study of the slides revealed low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, LAMN. Pathomorphological stage was diagnosed as pT4a Nx since it has perforated visceral peritoneum. The lesion was located within the wall of the caecum and the proximal part of the appendix (Figure 6). There were some acellular mucin pools in mesentery and in the intestinal wall. Appendiceal wall shown widespread epithelial denudation with the atrophy of underlying lymphoid tissue. Multiple blocks were required to demonstrate tumor cells. Focally appendiceal mucosa presented epithelium with villous morphology covered with cells mostly without atypia. There were some neoplastic epithelial cells with low grade dysplasia lying on fibrous stroma. The greatest part of the lesion consisted of the epithelial cells lying in the lakes of mucus within the lumen of the appendix. High grade dysplasia was not found.

Discussion

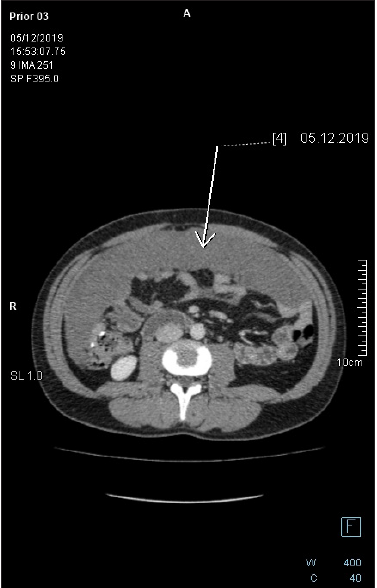

Due to its low prevalence, management of LAMN is not well described in literature. No prospective trials have been designed and conducted so far, which implicates an approach similar to colon cancer. For localized LAMN limited to vermicular appendix, simple appendectomy is advised [12]. Right hemicolectomy should be considered if tumor invades the base of appendix, has high mitotic rate, size >2cm and/or positive margin [13]. The use of adjuvant chemotherapy based on 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) for localized LAMN is still discussed. It is suggested in case of lymph node involvement or perforation. Treatment of advanced LAMN with peritoneal metastasis is a combination of serial debulking surgeries with intraoperative HIPEC infusion [14]. The term HIPEC refers to hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy-heated chemotherapy is delivered directly into peritoneum. It allows to minimize systemic consequences of high-dose therapeutic agents (Figure 7). Preferred substances are: 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), cisplatin, oxaliplatin and mitomycin C [15]. In addition, hyperthermia promotes production of heat shock proteins with cytotoxic effects on cells and tissues [16]. HIPEC should be reserved for patients after complete cytoreductive surgery (CRS). The completeness of cytoreduction (CCR) is assessed with CCR Score-an index that quantifies the extent of residual disease (RD) at the end of surgical procedure [17]. CCR0 means that there is no macroscopic residual disease, CCR1-residual tumors are smaller than 2.5mm, CCR2- residual tumors between 2.5-25mm, CCR3-residual tumors bigger than 25mm. CCR0 and CCR1 represent complete cytoreduction. In a multicenter study conducted in 2012 by Chua et al. [15]. regarding outcome of pseudomyxoma peritonei treatment, incomplete cytoreductive surgery was identified as the strongest predictor for a poorer progression-free survival [15]. Results of treatment of 385 patients with peritoneal surface spread of appendiceal malignancy described by Sugar baker and Chang in 1999 showed, that the 5-year survival rate for patients with incomplete cytoreduction is 20% [18]. Peritoneal cancer index (PCI) helps to estimate the probability of achieving complete cytoreduction and therefore allows to make surgical decisions before laparotomy [19]. The index assesses the extent of peritoneal cancer throughout the peritoneal cavity. The peritoneal cavity is divided in 13 regions. In each of the regions, the size of the largest tumor is measured. If no tumor is found a score 0 is assigned, 1 point is for tumor smaller than 0.5cm, 2 points for tumors measuring 0.5-5cm and 3 points for lesions bigger than 5cm. Total sum of the scores gives peritoneal cancer index. PCI>20 indicates a low complete cytoreduction probability [19].

Figure 7: Axial-CECT of the mid-abdomen reveals large pericolonic mucinous lesion. The lesion is homogenous with no soft tissue component, no appreciable septation nor calcification. There is no fat stranding in the adjacent fat tissue.

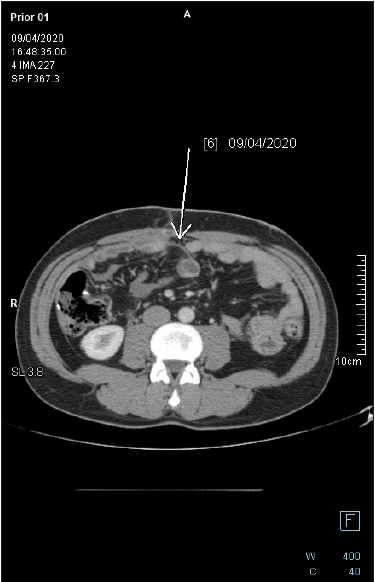

Gold standard in the management of peritoneal metastasis of LAMN is cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC without adjuvant, systemic chemotherapy [20]. According to studies by Chua [15], Shaib [21], Baratti [22] and many others, the use of systemic chemotherapy was associated with worse overall survival and shorter progression-free survival. It can be explained by poor efficacy of chemotherapy, its side effects and delay of surgical treatment. Chemotherapy is reserved for patients for whom, due to unresectable or relapsed lesions, surgical resection is not suggested. At present, there is no standard palliative systemic chemotherapy for LAMN, although drugs used for colorectal cancer may be offered to patients. Piet et al. [23]. in a study from 2014 examined effectiveness of FOLFOX-4 chemotherapy in 20 patients with peritoneal pseudomyxoma [23]. 4 (20%) underwent partial response (PR), 9 (45%) showed stable disease (SD), 7 (35%) had progressive disease (PD). Median progression free survival (PFS) was 8 months. Despite not promising results, 2 patients with initially unresectable lesions, went laparotomy-1 of them achieved complete cytoreduction (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Follow-up axial-CECT of the midabdomen reveals complete regression of the pericolonic mucinous lesion. There is no fat stranding in the adjacent fat tissue.

Conclusion

Orphan diseases cause a huge diagnostic and therapeutic problem for physicians. Symptoms are not typical, laboratory results and radiology images can bring further difficulties. Treatment of LAMN require prospective trials, as no official recommendations are available nowadays.

References

- Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zarchorowania and deaths from malignant neoplasms in Poland. National Cancer Registry, National Oncology Institute Maria Skłodowskiej-Curie-National Research Institute, Poland.

- Kaczmarkiewicz C, Grzybowski Z, Rzeszutek M (2004) Adenocarcinoma of the appendix. Pol Przegl CHir 76: 399-402.

- McCusker ME, Cote TR, Clegg LX (2002) Primary malignant neoplasm of the appendix: a population-based study from the surveillance, epidemiology and end-results program, 1973-1998. Cancer 94(12): 3307-3312.

- Collins DC (1955) A study of 50, 000 specimens of the human vermiform appendix. Surg Gynecol Obstet 101(4): 437-445.

- Berger A (1882) A case of appendage cancer. Ber Kilin Wochenschr 19: 610-619.

- Kshirsagar AY, Desai SR, Pareek V (2004) Primary adenocarcinoma of the vermiform appendix: A case report. J Indian Med Assoc 102: 262-262.

- Nitecki SS, Wolff BG, Schlinkert R (1994) The natural history of surgically treated primary adenocarcinoma of the appendix. Ann Surg 219(1): 51-57.

- Hananel N, Powsner E, Wolloch Y (1998) Adenocarcinoma of the appendix: An usual disease. Eur J Surg 164(11): 859-62.

- Kelly KJ (2015) Management of appendix cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 28(4): 247-255.

- Carr NJ, Cecil TD, Mohamed F, Sobin LH, Sugarbaker PH et al. (2016) A Consensus for classification and pathologic reporting of pseudomyxoma peritonei and associated appendiceal neoplasia: The results of the peritoneal surface oncology group international (PSOGI) modified delphi process. Am J Surg Pathol 40(1): 14.

- Bartlett DJ, Thacker PG Jr, Grotz TE, Graham RP, Fletcher JG, et al. (2019) Mucinous appendiceal neoplasms: Classification, imaging, and HIPEC. Abdom Radiol (NY) 44(5): 1686-1702.

- Yantiss RK, Shia J, Klimstra DS, Hahn HP, Odze RD, et al. (2009) Prognostic significance of localized extra-appendiceal mucin deposition in appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 33(2): 248-255.

- Gonzalez-Moreno S, Sugarbaker PH (2004) Right hemicolectomy does not confer a survival advantage in patients with mucinous carcinoma of the appendix and peritoneal seeding. Br J Surg 91(3): 304-311.

- Jacquet P, Stephens AD, Averbach AM, Chang D, Ettinghausen SE, et al. (1996) Analysis of morbidity and mortality in 60 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis treated by cytoreductive surgery and heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer 77(12): 2622-2629.

- Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, Levine EA, Glehen O, et al. (2012) Early and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 30(20): 2449-2456.

- Gerweck LE (1985) Hyperthermia in cancer therapy: The biological basis and unresolved questions. Cancer Res 45(8): 3408-3414.

- Jo MH, Suh JW, Yun JS, Namgung H, Park DG, et al. (2016) Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer: 2-year follow-up results at a single institution in Korea. Ann Surg Treat Res 91(4): 157-164.

- Sugarbaker PH, Chang D (1999) Results of treatment of 385 patients with peritoneal surface spread of appendiceal malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol 6(8): 727-731.

- Sugarbaker PH, Jablonski KA (1995) Prognostic features of 51 colorectal and 130 appendiceal cancer patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis treated by cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg 221(2): 124-132.

- Shaib WL, Assi R, Shamseddine A, Alese OB, Staley C, et al. (2017) Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: Diagnosis and management. The Oncologist 22(9): 1107-1116.

- Shaib WL, Martin LK, Choi M, Chen Z, Krishna K, et al. (2015) Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy following cytoreductive surgery improves outcome in patients with primary appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma: A pooled analysis from three tertiary care centers. The Oncologist 20(8): 907-914.

- Baratti D, Kusamura S, Nonaka D, Langer M, Andreola S, et al. (2008) Pseudomyxoma peritonei: Clinical pathological and biological prognostic factor in patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Ann Surg Oncol 15(2): 526-534.

- Pietrantonio F, Maggi C, Fanetti G, Iacovelli R, Bartolomeo M, et al. (2014) FOLFOX-4 chemotherapy for patients with unresectable or relapsed peritoneal pseudomyxoma. Oncologist 19(8): 845-850.

© 2020 Jiayu Wang. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)