- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Colonoscopic Results in Patients with Hartmann’s Colostomy

Young Hun Kim and Kyung Jong Kim*

Department of Surgery, Chosun University College of Medicine, South Korea

*Corresponding author: Kyung Jong Kim, Department of Surgery, Chosun University Hospital. 365 Pilmun-daero, Dong-Gu, Gwang-ju, Korea

Submission: June 25, 2020;Published: July 07, 2020

ISSN 2637-7632Volume4 Issue5

Abstract

Purpose: Colonoscopy in patients with colostomy after Hartmann’s procedure could be a quite challenging or special situation. This study aimed to analyze the Colonoscopic results in patients with Hartmann’s colostomy.

Methods: Total 79 consecutive patients undergoing colonoscopy before reversal of Hartmann’s operation were retrospectively reviewed. The procedure was performed first through the anus for evaluation of distal colonic/rectal stump, and then through the colostomy to the cecum or terminal ileum for proximal colon evaluation.

Results: Cecal insertion was possible in 72 patients; the success rate was 91.1%. The causes of failure were poor or inadequate bowel preparation in 4 patients, colostomy stricture, colonic stenosis, and angulation in 1 patient, respectively. Completeness of the bowel preparation was poor in 21 patients and inadequate in 6 patients, showing bad preparation in 33.3%. Mean Cecal insertion time from colostomy was 5.1 minute. The Colonoscopic finding of proximal part to colostomy was nonspecific in 38 patients, polyp(s) detection in 15 patients, and diverticulosis in 15 patients. In the examination of distal stump, mean length was 18.4cm, two patients couldn’t evaluate the full length of distal stump, and 11 patients showed abnormal findings including polyps, diverticular, and inflammation.

Conclusion: These results suggest that most patients with colostomy can evaluate the remained colon or rectum without technical difficulty. However bowel preparation is the most important point to complete the evaluation of the colon in patients with colostomy.

Keywords: Colonoscopy; Colostomy; Hartmann’s procedure; Insertion time; Bowel preparation

Introduction

Hartmann’s procedure is a common surgical technique for emergency surgery of colorectal diseases when primary anastomosis is not a feasible option [1,2]. After resecting the lesion, the distal end is closed and end colostomy is performed on the proximal end. In general, it is performed on the left colon or rectal lesion.

In Korea, westernization of diet and aging in the society has led to an increased incidence of colorectal cancer as well as various benign colorectal diseases. These diseases are a frequent cause of emergency surgery, and Hartmann’s operation is performed in the high-risk group such as severe peritonitis or elderly patients. After the Hartmann’s procedure, patients defecate through a stoma, which severely undermines their quality of life. Thus, stoma reversal is generally performed 1-2 months later once the patient is stabilized. If the colostomy closure is scheduled, it is important to check whether the previous disease has improved; moreover, the possibility of other serious colorectal diseases should be evaluated. In such cases, colonoscopy may be the most useful test. Colonoscopist needs to know basic information and characteristics about stomas and to have the practical techniques of colonoscopy through the colostomy. However, clinical results of colonoscopy in colostomy patients are extremely scarce. Therefore, this study aimed to report the clinical outcomes of colonoscopy in patients with Hartmann’s colostomy.

Patients and Methods

Consecutive patients who underwent colonoscopy prior to Hartmann’s operation reversal were enrolled in this study. All procedures were continuously performed by one colonoscopist/ colorectal surgeon between September 2011 and August 2018. The same type of endoscope (CF H260AI or CF H260AL: Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was usually used, and smaller diameter scope (PCF-Q260AI) was used in case of colostomy stenosis. This study retrospectively analyzed the medical records under the approval of institutional review board. The following results were collected and analyzed: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), underlying disease, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, the causative disease for Hartmann’s operation, position of colostomy and abnormal findings, insertion time, completeness of bowel preparation, success rate, reason of endoscopy failure, and colonoscopy findings (e.g., diverticula, polyp). Cecal insertion was defined as cases where the ileocecal valve or appendix orifice was found; insertion time was defined as the time from the stoma to the cecum. Patients took polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4L or PEG 3350 2L for bowel cleaning at least until 3 hours before the test according to the manufacturer’s manual. Bowel preparation was measured with an Aronchick score, and it was classified as excellent, good, fair, poor, and inadequate [3]. For colonoscopy, first, the rectal remnant was examined through the anus, and then an endoscope was inserted through the stoma to the cecum or the terminal ileum. After full insertion, abnormal findings were examined while slowly pulling out the endoscope. Cecal insertion time was defined as time from the stoma to the cecum and expressed in minutes, and in which cecal insertion was unsuccessful were defined as failed cases.

Results

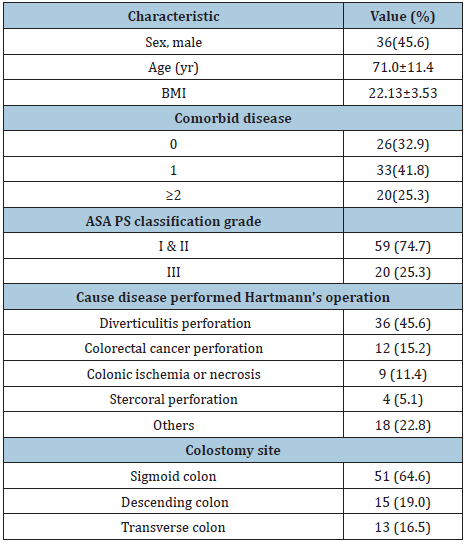

Clinical characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1: Clinical details of the patients (n=79).

Colonoscopy was consecutively performed in 79 patients, 45.6% of whom were men, and the mean age was 71.0 (±11.4) years. Mean BMI was 22.13 (±3.53) kg/m2. A total of 67.1% of the patients had one or more comorbidities, and 25.3% had an ASA score III. The most common causative disease for Hartmann’s operation was diverticulitis with perforation (45.6%), and other causes included perforation caused by colorectal cancer (15.2%), colon ischemia or necrosis (11.4%), perforation caused by faces (5.1%), and other causes (22.8%). In terms of location of colostomy, sigmoid colostomy was the most common (64.6%), followed by descending colostomy (19.0%) and transverse colostomy (16.5%).

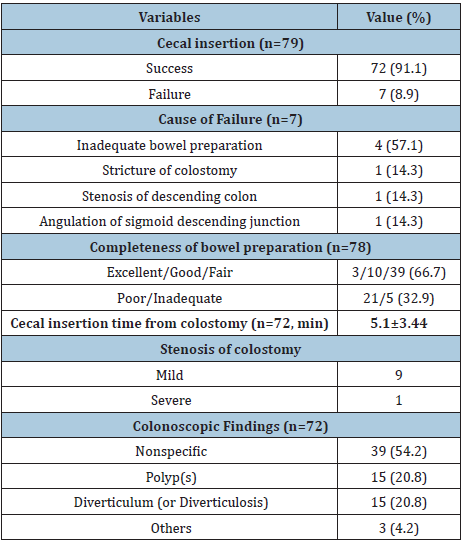

Colonoscopic results of the proximal part (Table 2)

Table 2: Colonoscopic Results (Proximal part of the colostomy).

For 72 out of 79 patients, the endoscope could be inserted into the cecum through colostomy, with a success rate of 91.1%. Cecum insertion failed in 7 patients, and the most common cause of failure was inappropriate bowel preparation (n=4), and other causes were stricture of the colostomy that hindered endoscopy from the start (n=1), stenosis of the descending colon (n=1), and angulation in the sigmoid descending junction (n=1). Regarding the completeness of bowel preparation, there were 3 patients with excellent preparation; 10, good; 39, fair; 21, poor; and 5, inadequate, showing that 32.9% of the patients showed poor or inadequate bowel preparation.

In 72 patients with successful cecal insertion, the mean time was 5.1 (±3.44) minutes. The longest cecal insertion time was 15.7 minutes for a 73-year-old female patient. Mild stomal stenosis, where only a paediatric endoscope could pass, was observed in 9 patients, and severe stomal stenosis, where no endoscope could be passed, was observed in 1 patient. Regarding Colonoscopic findings, 54.2% had no notable findings, but polyp(s) were observed in 15 (20.8%) patients and diverticula were observed in 15 (20.8%) patients.

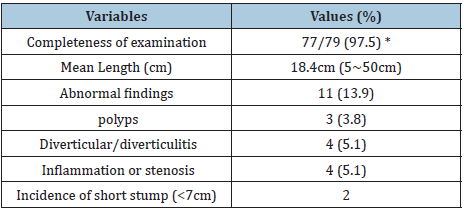

Colonoscopic results of the distal stump (Table 3)

Table 3: Colonoscopic Results of the distal stump.

*2 cases; 1 case; too long segment, 1 case; angulation at the RS junction

Regarding the distal rectal stump examination, most patients had lumps of scybala (old hard stools), and average length of remained stump was 18.4cm, ranging from 5cm to 50cm. Two patients were not able to completely be examined the distal stump because of too long remained stump (about 50cm) in one patient and angulation of rectosigmoid junction in the other patient. Abnormal finding was observed in 11 patients (13.9%), polyp in 3 patients, diverticular in 4 patients, and inflammation or stenosis in 4 patients. Short length of distal rectal stump (less than 7cm) showed in 2 patients.

Discussion

This study investigated the clinical results of colonoscopy in patients undergoing Hartmann’s colostomy. The success rate was 91.1%, and mean cecal insertion time was 5.1 minutes and poor or inadequate bowel preparation was the major cause of failure of complete examination. Hartmann’s operation is a common technique used in emergency surgeries of various diseases. End colostomy is performed after the surgery; therefore, it causes significant discomfort to patients. Most patients-despite having serious underlying disease-wish to undergo a reversal surgery as soon as possible. However, the actual rate of reversal surgery ranges 56%-100% across reports [2,4,5]. Before restoration of bowel continuity, it seems necessary to check whether there are any abnormalities in the remaining colon and rectum. However, there is no clear consensus on whether colon/rectum testing prior to reversal surgery is necessary and, if so, what tests should be used. Ballian et al. [6] reported that patients who have no symptoms prior to the Hartmann’s reversal can undergo the surgery safely, even without examination of the distal colonic/rectal remnant, and that patients who do have symptoms may undergo radiologic and/or endoscopic studies. However, that study lacks data on the examination of proximal part of colostomy. Therefore, there is a need to make consensus about the method of colon/rectum evaluation prior to Hartman’s reversal. At author’s institution, colonoscopy is routinely performed on all patients to check for colonic/rectal abnormalities prior to Hartmann’s reversal, unless the patient refuses the test.

Investigation of the cecal insertion rate in patients with colostomy is virtually lacking. In a study that examined the factors affecting colonoscopy insertion time in patients undergoing left-side colorectal resection, where some patients underwent colostomy, Jang et al. [7] reported 98.9% success rate in patients with colostomy and 97.0% success rate in those not having colostomy, with no significant difference between the 2 groups. These success rates are higher than the cecal insertion rates of 91.1% reported in our study. But in general, cecal insertion rates vary widely, some studies reporting 77% [8]. When performing colonoscopy in patients having colostomy, increasing the success rate is important, but safe procedure without causing complications is more important, as there is a high possibility of intestinal adhesion or inflammation in the abdominal cavity according to previous surgery. Furthermore, any colonic or rectal segment not examined during colonoscopy may be checked in the following reversal surgery; therefore, forced colonoscopy insertion should be avoided in colostomy patients. Cecal insertion time is the time from the stoma to the cecum, and the mean cecal insertion time in our study was 5.1 (±3.44) minutes. In a prospective study on the general population, the mean cecal insertion time was 4.70-5.02 minutes [9]. In a retrospective study including colostomy patients, the mean cecal insertion time for experienced and less experienced endoscopists was 5.3 and 6.6 minutes, respectively [7]. This is similar to our overall findings. Taken together, there is not much difference in the difficulty of colonoscopic insertion between the general population and patients with colostomy.

In the present study, the most common cause of colonoscopy failure was poor or inadequate bowel preparation; 32.9% of the patients had poor or inadequate preparation; however, the rate was only 14.8% in Jang et al. [7]. The high rate of poor or inadequate bowel preparation in our study may be attributable to the fact that our patients were relatively older than those in other studies. It is highly possible that older patients may not fully comply with the method or dose of prescribed bowel preparation regimen. However, it is also possible that the method of bowel preparation applied to the general population may be inadequate for patients with stoma; therefore, additional studies are needed on this matter. One of the stoma-related causes behind the failure of colonoscopy in this study was stomal stenosis, a complication that occurs in about 2%-15% of colostomy patients [10]. When stomal stenosis is found in patients with stoma, it is difficult to even begin colonoscopy. Stomal stenosis can be divided into severe stenosis, which makes endoscopic insertion impossible, and mild stenosis, in which only an endoscope of a small diameter can be inserted. In the present study, mild stenosis, where a pediatric endoscope can only be inserted, was relatively common, at about 11.4%. When the lumen of stoma is smaller than the diameter of the endoscope, it may be possible to insert the endoscope after dilatation of the stoma with finger. This study has a few limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and a retrospective analysis was performed. To address this shortcoming, prospective studies on a larger population are needed; furthermore, analyzing the results of only one endoscopist may be a source of bias. In recent years, the number of patients with stoma seems to be consistently increasing. This increase is attributed to an increase in not only colorectal cancer but also various benign diseases such as diverticulitis and inflammatory bowel disease as a result of westernization of diet and aging of population. Even in these patients with colostomy, colonoscopy is also necessary for the diagnosis of new colorectal diseases and evaluation of existing diseases. To perform effective and safe colonoscopy in these patients, the colonoscopist seems to have to be familiar with the characteristics of the colostomy, as well as the medical record of the patients past surgery.

Conclusion

These results suggest that most patients with colostomy can evaluate the remained colon or rectum without technical difficulty. However, bowel preparation is the most important point to complete the evaluation of the colon in patients with colostomy.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by research fund from Chosun University in 2017.

References

- Haas PA, Haas GP (1988) A critical evaluation of the Hartmann's procedure. Am Surg 54(6): 380-385.

- Schein M, Decker G (1988) The Hartmann procedure. Extended indications in severe intra-abdominal infection. Dis Colon Rectum 31(2): 126-129.

- Bechtold ML, Mir F, Puli SR, Nguyen DL (2016) Optimizing bowel preparation for colonoscopy: A guide to enhance quality of visualization. Ann Gastroenterol 29(2): 137-146.

- Salem L, Anaya DA, Roberts KE, Flum DR (2005) Hartmann's colectomy and reversal in diverticulitis: A population-level assessment. Dis Colon Rectum 48(5): 988-995.

- Sweeney JL, Hoffmann DC (1987) Restoration of continuity after Hartmann's procedure for the complications of diverticular disease. Aust N Z J Surg 57(11): 823-825.

- Ballian N, Zarebczan B, Munoz A, Harms B, Heise CP, et al. (2009) Routine evaluation of the distal colon remnant before Hartmann's reversal is not necessary in asymptomatic patients. J Gastrointest Surg 13(12): 2260-2267.

- Jang HW, Kim YN, Nam CM, Lee HJ, Park SJ, et al. (2012) Factors affecting colonoscope insertion time in patients with or without a colostomy after left-sided colorectal resection. Dig Dis Sci 57(12): 3219-3225.

- Bowles CJ, Leicester R, Romaya C, Swarbrick E, Williams CB, et al. (2004) A prospective study of colonoscopy practice in the UK today: are we adequately prepared for national colorectal cancer screening tomorrow? Gut 53(2): 277-283.

- Jun JH, Han KH, Park JK, Seo HI, Kim YD, et al. (2017) Randomized clinical trial comparing fixed-time split dosing and split dosing of oral Picosulfate regimen for bowel preparation. World J Gastroenterol 23(32): 5986-5993.

- Shabbir J, Britton DC (2010) Stoma complications: A literature overview. Colorectal Dis 12: 958-964.

© 2020 Kyung Jong Kim. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)