- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Currarino Syndrome: Autosomal Dominant Sacral Agenesis Application of Sacral Nerve Stimulation in Currarino Syndrome

Adam Studniarek*, Artyom Khurshudyan, Amir Esparza Monzavi C, Gerald Gantt, Anders Mellgren and Johan Nordenstam

Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery, USA

*Corresponding author: Adam Studniarek, Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, USA

Submission: February 20, 2020;Published: March 10, 2020

ISSN 2637-7632Volume4 Issue4

Abstract

Introduction: Currarino Triad is a complete form of Currarino Syndrome which consists of sacral anomaly, anorectal malformations, and a presacral mass. Individual case reports and small case series regarding the diagnosis and treatment have been described in the literature. Here we present a case of a young woman with Currarino Syndrome, managed with Sacral Nerve Stimulation (SNS).

Case report: A 32-year-old female presented with Currarino triad including anal atresia, dysplasia of the sacrum, and presacral teratoma with tethered cord. The patient is of Polish decent and for many years received treatment for chronic constipation in Poland. She underwent multiple surgeries to correct the anal atresia, first when she was thirteen years old with unsatisfactory results further requiring diamond flap anoplasty after her arrival to the United States at the age of twenty-nine. She has also had chronic, refractory constipation despite aggressive medical treatment. A sacral nerve stimulator was implanted to treat her refractory constipation with promising results.

Discussion: Our experience with SNS treatment for this patient with Currarino Syndrome provides encouraging results for the use of SNS in the treatment of constipation in patients with previously distorted anatomy. Given the success of SNS in adults with other congenital anal malformations, and the success with this patient, SNS may have a promising future for improving bowel dysfunction and quality of life in Currarino Syndrome patients.

Conclusion: Sacral nerve stimulation can be a successful surgical approach in managing chronic, refractory constipation, demonstrating possible future applicability for Currarino Syndrome patients struggling with chronic constipation. Further large cohort studies are necessary to evaluate the success rate of sacral nerve stimulation in patients with chronic constipation.

Introduction

Currarino Syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant condition, first described by Guido Currarino, a radiologist, in 1981 [1]. The classic presentation of the syndrome consists of at least three anomalies and is called the Currarino triad. The triad has only been observed in 20% of cases of Currarino syndrome [2]. The triad consists of sacral anomaly, anorectal malformations, and presacral mass [3]. Each of these conditions has many clinical presentations. Sacral agenesis refers to conditions including aplasia, hemiplegia, and dysplasia of the sacrum and coccyx, hemi sacrum, and bifid sacrum. Anorectal malformations also come in many variations. These include rectoperineal, rectourethral, and recto vestibular fistulas, as well as anorectal stenosis, with anorectal stenosis being the most common presentation. Finally, these patients present with a pre-sacral mass which can include mature or immature teratomas, sacral meningocele, duplication cysts of the rectum, or a dermoid cyst [4].

Currarino Syndrome affects about 1-9/100,000 people [5]. Fifty percent of these patients are accounted for by an autosomal dominant inherited mutation in gene HLXB9 [6]. While the syndrome itself has the aforementioned presentation, Currarino Syndrome (CS) belongs to the group of neurenteric malformations with the most common symptoms including infantile bowel obstruction or chronic constipation in childhood [6]. This case report demonstrates a case of a thirty-two-year-old female with a late presentation of the entire constellation of symptoms. The subsequent post-operative complications associated with unique presentation of a full Currarino triad were treated by sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) to improve the patient’s symptoms. Sacral neuromodulation is a technique that has been shown in multiple studies to improve both fecal incontinence and constipation. The major indication for SNS is fecal incontinence, not responding to conservative treatment, but this relatively new method of incontinence management has also been successfully applied in patients with severe, refractory constipation [7]. To our knowledge, this is the first case of a patient with a history of Currarino Syndrome and difficult post-operative anatomy who was successfully treated with SNS therapy [8,9].

Case Presentation

A 32-year-old female presented to the colorectal surgery clinic with a diagnosis of Currarino syndrome and a complex history of surgical management during her previous hospitalizations in Poland where she previously resided. Her family history was limited but significant for a sister with a past surgical history of a secretory and a suspicion of Currarino Syndrome. Additionally, the patient’s niece and a three-week-old nephew were diagnosed with Currarino Syndrome which confirms the familial inheritance of the disease. Our patient was diagnosed late during her teenage years since the initial symptoms had not caused any significant decrease in her quality of life. In 1999, the initial presentation of multiple congenital anomalies raised a suspicion of a syndromic disease among the physicians taking care of the then 13-year-old patient. The initial presentation of constipation, recto-vaginal fistula and anal stricture raised a suspicion of Hirschsprung’s disease, a condition often misdiagnosed in patients with Currarino Syndrome. At the time of her initial hospitalization, a diverting ostomy was created to allow for adequate stool output. Subsequently, she underwent anal dilation and Kasai rectoplasty involving rectal myotomy and segmental colectomy with posterior triangular colonic flap. This procedure was considered a radical operation for Hirschsprung’s disease at the time of initial publication by Kasai et al. [10] demonstrating successful results in twelve out of fifteen described patients. The anorectal motility studies after rectoplasty with posterior triangular colonic flap demonstrated satisfactory postoperative continence in 18 out of 22 patients evaluated by Suzuki et al. [11]. Similarly, our patient did not have any signs of fecal incontinence post-operatively and during teenage years. The patient presented again three years after the initial surgery, this time with a new onset of lower extremity numbness and paresthesia’s. She was found to have a pre-sacral mass, a tethered spinal cord syndrome, and an anterior sacral meningocele, consistent with the previously suspected diagnosis of Currarino syndrome. She was diagnosed with Currarino Syndrome at the age of seventeen. Subsequently, the patient underwent resection of the pre-sacral mass, separation of meninges from the sacral mass, and diverting colostomy creation. The resected specimen was analyzed, and was found to be a mature, benign teratoma.

That same year after presacral mass resection, the patient underwent her first reconstruction of the anterior portion of the anus and external anal sphincter. A number of repairs including anoplasty and external anal sphincter repairs were performed to correct residual anal stenosis and yet maintain function and continence. After colostomy reversal the following year, the patient initially maintained her continence, however she developed symptoms of constipation requiring further medical and surgical treatment. The medical treatment consisted of rectal enemas, lavage, Dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (Bisacodyl), and stool softeners administration to help her manage constipation. As the patient continued to have worsening constipation, refractory to medical treatment, a number of surgical options were considered. The first approach was the creation of a Malone stoma and Malone antegrade continence enema (MACE) with a hope that daily irrigations would help with her constipation.

Figure 1: Chronic constipation in a patient with Currarino Syndrome.

Figure 2: SNS therapy in a patient with Currarino Syndrome.

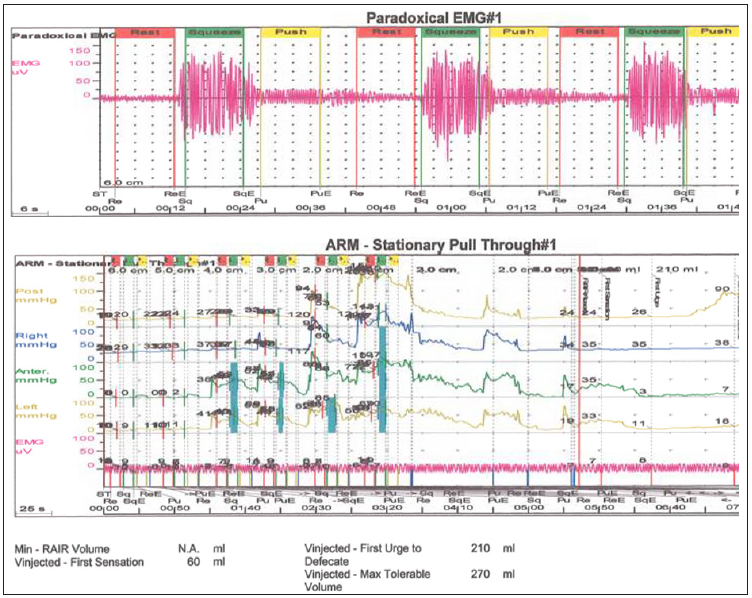

Over the next few years, she experienced a number of complications requiring further surgical revisions of her Malone stoma. One year after her Malone stoma creation, she presented with abdominal pain and an inability to irrigate her stools. She was found to have neurogenic bladder and ectasia of the rectum leading to a megarectum which also contributed to her worsening constipation. According to previous reports, rectosigmoid ectasia is associated with anorectal anomaly repair which could have contributed to her symptoms [12]. With the worsening symptoms and diagnosis of megarectum, patient underwent transabdominal proctectomy with colo-anal anastomosis. Throughout the next few years, patient underwent additional procedures including rectovaginal fistula repair and exploratory laparotomy for recurrent small bowel obstructions. At this point, the severe constipation progressed as well as the abdominal and pelvic adhesions due to multiple surgical interventions. In 2015, twelve years after the diagnosis of Currarino syndrome, the patient relocated to the United States where further care was continued. Due to persistent symptoms of chronic constipation (Figure 1), the medical and surgical treatment options were limited, therefore a decision was made to implant a sacral nerve stimulator (SNS) (Figure 2). Prior to SNS implantation an extensive work up was completed including anal manometry (Figure 3). Finally, the following year, the patient had a Stage 1 SNS implantation along with an endodermal diamond flap repair for refractory constipation and residual anal stenosis, respectively. Given the patient’s positive results with the stage 1 SNS, she progressed to a permanent implant during stage II procedure two weeks later. Post-operatively the patient had satisfactory outcomes with no immediate post-operative complications. The SNS stimulator remains activated with one occurrence requiring battery change since the implantation with significant improvement in constipation symptoms. Patient currently has regular bowel movements every two days. The medical therapies for constipation including enemas and stool softeners are still administered. She has not experienced any adverse events associated with the placement of SNS electrode.

Figure 3: Anal manometry findings in a Currarino Syndrome patient with refractory constipation.

Discussion

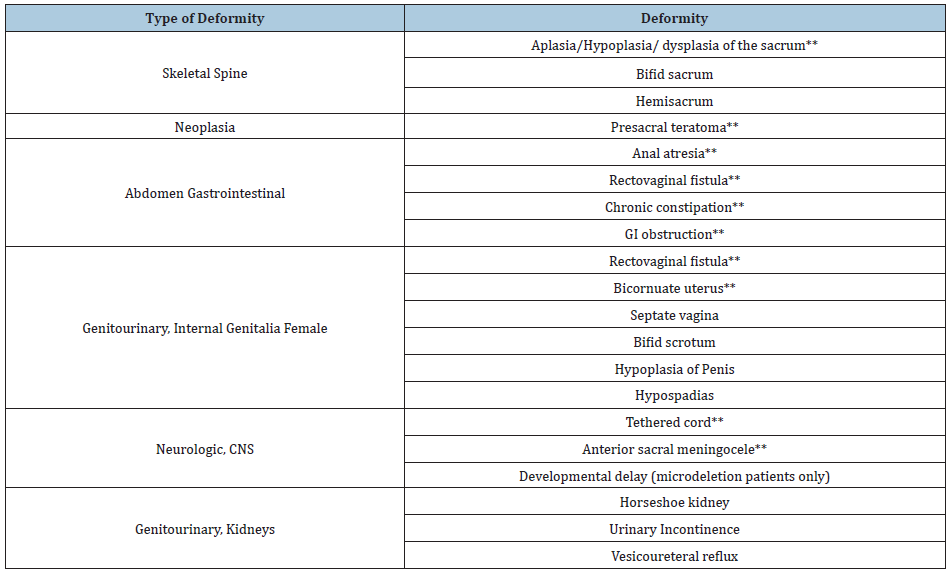

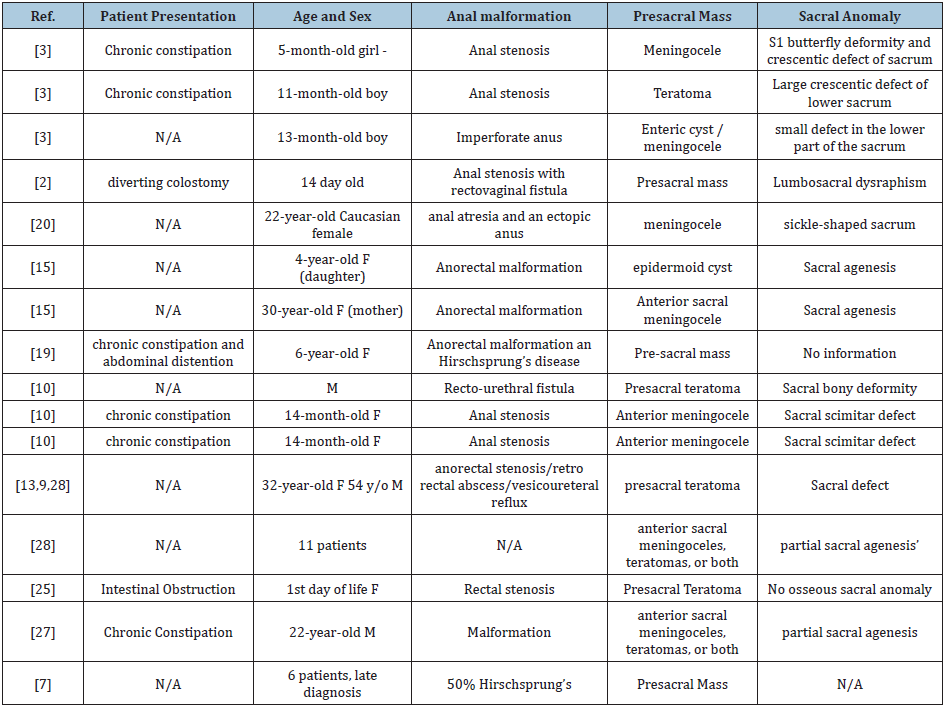

Currarino syndrome is rarely encountered in clinical practice and as a result, the diagnosis remains challenging for clinicians and surgeons. Currarino syndrome is considered a neonatal or even prenatal diagnosis since the most common anorectal symptoms can be present at birth. Cretolle et al. [13] reported prenatal diagnosis of Currarino syndrome by ultrasound at 22 weeks’ gestation. Despite early clinical presentation, the diagnosis is often very complex and therefore not established until later in life. The diagnosis of Currarino syndrome consists of a wide variety of early childhood symptoms often mimicking other more common conditions. It is usually diagnosed during the first years after a child is born as the anorectal anomalies can be observed. The constellation of different symptoms and clinical presentations (Table 1) have been previously described in a small number of individual case series since the first description by Dr. Currarino in 1981 (Table 2). While uncommon, late presentations of Currarino syndrome have also been described in the past [14].

Table 1: Clinical presentation of patients with Currarino Syndrome. (**conditions present in our patient).

Table 2: Currarino Syndrome case series.

Currarino Syndrome presents with a constellation of symptoms that often lead to multiple surgical interventions in order to improve the morbidity associated with the disease. The most common anorectal malformation in Currarino triad is anorectal stenosis which leads to the most common symptom in the Currarino triad, which is constipation [15]. Another but less frequent malformation in Currarino syndrome is complete anorectal atresia. Additionally, patients often present with pre-sacral mass. Based on previous reports, the presacral mass has been reported to be an anterior sacral meningocele in 60% of patients, a teratoma in 25%, and other tumors in the remaining 15% of patients [16]. Historically, malignant transformation has been observed in Currarino syndrome patients with presacral masses [17,18]. Fortunately, this patient’s mature teratoma was not found to be malignant, and no further post-operative treatment was required for the mass.

Our case also demonstrates a patient who had a recto vaginal fistula which allows for the passage of stool through the fistula even in patients with atresia. This presentation masked her condition and did not allow for early diagnosis. The refractory constipation in this case was likely caused by anatomical alterations with residual anal stenosis as well as functional causes. Although SNS has been successfully used in patients with sphincter degeneration and weakness, and possibly in those with sphincter disruption, sacral nerve stimulation markedly improves fecal incontinence [19], there is no evidence regarding its use in patients with Currarino Syndrome.

Stage I of SNS is classified as a test phase to allow physicians to assess benefits of a future permanent sacral neuromodulation. A device is surgically implanted and sends mild electrical impulses to the sacral nerve which can activate or inhibit the nerve based on impulse. The finding of an increased squeeze pressures during SNS treatment suggests that SNS augments striated anal sphincter muscle activity which leads to either hypertrophy of existing muscle fibers or alteration in muscle fiber type which plays a key role in the treatment of fecal incontinence [19]. Previous studies have also demonstrated significant improvement in rectal sensation to distention which is one of the theories behind the improvement in constipation after SNS implantation [20,21]. The most commonly described adverse effects related to SNS implantation are infection, pain and lack of intended results which often lead to SNS electrode explanation. According to a number of studies the explanation rates vary from 7.8% to 12.7% and reoperation rates from 14.2% to 23.9% [22].

Our experience with this patient provides a successful utilization of SNS in the treatment of constipation in patients with previously distorted anatomy. While long-term use and success rate of SNS in Currarino Syndrome patients cannot be established due to lack of large cohorts of patients with this condition, this case demonstrates its feasibility. The use of SNS was specifically found to be useful in patients with a morphologically intact sphincter apparatus, whose incontinence stems from a functional rather than an anatomic deficit. The way in which SNS helps such patients is thought to be by enhancing striated muscular activity and neuromodulating sacral reflexes that regulate rectal sensitivity and contractility [23]. The SNS alters afferent input to the sacral spinal cord and helps to better control both incontinence and constipation [23]. The challenges for direct application of SNS lie in the fact that Currarino Syndrome patients present with a multitude of anatomic deficits along with functional deficits. Patients with this congenital triad often undergo multiple surgical procedures which lead to distorted pelvic anatomy and associated complications. Therefore, further use of SNS needs to be assessed on a case by case basis.

The use of SNS has been described in patients with other anorectal malformations such as imperforate anus which was one of the first cases where SNS was used in adults with congenital anal malformation [24]. Additionally, SNS had historically been used in children with VACTRL, but it has not been used in adults with this syndrome [25]. Our case study showed its potential in the adult population with complex anorectal malformations. Given the previous success rates in individual anorectal malformation cases, it is not as surprising that this patient had positive results as well. The main indication for SNS implantation is fecal incontinence, however more recent data have shown that it can also be used for chronic refractory constipation as presented here [20]. The patient underwent permanent sacral nerve stimulation with a primary goal of improvement in constipation which was achieved despite difficult, distorted pelvic anatomy. Given the success of SNS in adults with other congenital anal malformations, and the success with this patient, SNS has a promising future for improving bowel dysfunction and quality of life in Currarino Syndrome patients. This case can help to pave the way for future larger studies including patients with anorectal malformations.

Conclusion

Currarino triad is a rare congenital disease and its diagnosis is even more uncommon in the adulthood. The most common symptom related to this syndrome is chronic constipation, and early diagnosis and treatment with SNS can significantly improve quality of life for some of these patients. The use of SNS in this case demonstrated a successful surgical approach to treatment of refractory constipation in a patient with difficult congenital anorectal malformations. Long term follows up and larger cohort studies will be necessary to determine the efficacy and application of SNS in adults with similar colorectal anomalies.

References

- Bryant T (1838) Case of deficiency of the anterior part of the sacrum with a thecal sac in the pelvis, similar to the tumour of spina bifida. Lancet p. 358.

- Guido C (1981) Triad of anorectal, sacral, and presacral anomalies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 137(2): 395-398.

- Kurosaki MMD, Kamitani HMD, Anno YMD, Watanabe TMD, Hori TMD, et al. (2001) Complete familial Currarino triad. Report of three cases in one family. J Neurosurg 94(1): 158-161.

- Yashushi I, Iinuma Y, Iwafuchi M, Uchiyama M, Yagi M, et al. (2000) A case of currarino triad with familial sacral bony deformities. Pediatric Surgery International 16: 134-135.

- Inserm, Orphanet, Currarino Syndrome, France.

- Baltogiannis N, Mavridis G, Soutis M, Keramidas D (2003) Currarino triad associated with hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 38(7): 1086-1089.

- Elkelini MS1, Abuzgaya A, Hassouna MM (2010) Mechanisms of action of sacral neuromodulation 21(Suppl 2): S439-446.

- Tracy H (2013) Long-Term Durability of Sacral Nerve Stimulation therapy for chronic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 56(2): 234-245.

- Tjandra JJ, Chan MK, Yeh CH, Murray-Green C (2008) Sacral nerve stimulation is more effective than optimal medical therapy for severe fecal incontinence: A randomized, controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum 51(5): 494-502.

- Kasai M, Suzuki H, O'hi R, O'htomo S (1977) Rectoplasty with posterior triangular colonic flap--a radical new operation for Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg 12(2): 207-211.

- Suzuki H, Tsukamoto Y, Amano S, Sakurai A (1984) Sakurai a motility of the anorectum after "rectoplasty with posterior triangular colonic flap" in Hirschsprung's disease. Jpn J Surg 14(4): 335-338.

- Keramidas DC, Soutis M, Mavridis G, Papandreou E (2005) Rectosigmoid ectasia associated with anorectal anomaly repair: experience with sigmoid anterior resection and endorectal pull-through. Eur J Pediatr Surg 15(4): 268-272.

- Crétolle C, Sarnacki S, Amiel J, Geneviève D, Encha-Razavi F, et al. (2007) Currarino syndrome shown by prenatal onset ventriculomegaly and spinal dysraphism. Am J Med Genet A 143A (8): 871-874.

- Ilhan H, Tokar B, Atasoy MA, Kulali A (2000) Diagnostic steps and staged operative approach in currarino's triad: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Childs Nerv Syst 16(8): 522-524.

- Moshekov E, Ionkov A (2006) Currarino syndrome--a case report. Khirurgiia (3): 59-60.

- Köchling J, Karbasiyan M, Reis A (2001) Spectrum of mutations and genotype-phenotype analysis in Currarino syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 9(8): 599-605.

- Marc Dirix, Tine van Becelaere, Lizanne Berkenbosch, Robertine van Baren, Rene M Wijnen, et al. (2015) Malignant transformation in sacrococcygeal teratoma and in presacral teratoma associated with Currarino syndrome: A comparative study. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50(3): 462-464.

- Sen G, Sebire N, Olsen O, Kiely E, Levitt G (2008) Familial Currarino syndrome presenting with peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour arising with a sacral teratoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50(1): 172-175.

- Brill SA, Margolin DA (2005) Sacral nerve stimulation for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 18(1): 38-41.

- Thomas GP, Dudding TC, Rahbour G, Nicholls RJ, Vaizey CJ (2013) Sacral nerve stimulation for constipation. Br J Surg 100(2): 174-181.

- Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA, Turner IC, Nicholls RJ, Woloszko J (1999) Effects of short term sacral nerve stimulation on anal and rectal function in patients with anal incontinence. Gut 44(3): 407-412.

- Bielefeldt K (2016) Adverse events of sacral neuromodulation for fecal incontinence reported to the federal drug administration. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 7(2): 294-305.

- Elkelini MS, Abuzgaya A, Hassouna MM (2010) Mechanisms of action of sacral neuromodulation. Int Urogynecol J 21 (Suppl 2): S439-S46.

- Eftaiha SM, Melich G, Pai A, Marecik SJ, Prasad LM, et al. (2016) Sacral nerve stimulation in the treatment of bowel dysfunction from imperforate anus: A case report. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 24: 115-118.

- Iinuma Y, Iwafuchi M, Uchiyama M, Yagi M, Kondoh K, et al. (2000) A case of currarino triad with familial sacral bony deformities. Pediatr Surg Int 16(1-2):134-135.

© 2020 Adam Studniarek. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)