- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Low Gastric Bicarbonate Secretions Seen in Cigarette Smokers

Faiza Ahmed2*, Ishita Gupta1 and Syed Siddiqi2

1Department of Medicine, India

2Department of Gastroenterology, USA

*Corresponding author: Faiza Ahmed, Department of Gastroenterology, USA

Submission: March 03, 2020;Published: March 09, 2020

ISSN 2637-7632Volume4 Issue3

Summary

Sucralfate drug is well known for its miraculous effects on gastroduodenal mucosa and its therapeutic effects on peptic ulcer, but its mechanism of action is still a mystery. This drug administration of 3g daily for 4-6 weeks is an effective treatment on gastric bicarbonate secretion. Our observational study was focused on gastric bicarbonate secretion in 14 healthy smokers and 11 healthy age and sex-matched nonsmoker volunteers. The outcome of the study suggested that smokers produced low gastric bicarbonate secretions compared to non-smokers.

Keywords: Low gastric bicarbonate; Cigarette smokers; Nicotine use; Gastric bicarb; Gastric secretions

Introduction

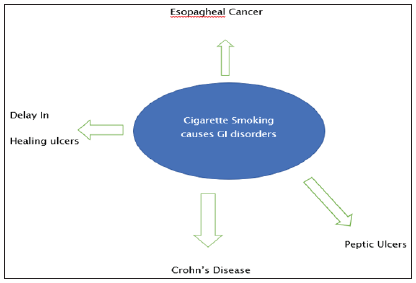

Cigarette smoking is associated with a plethora of gastrointestinal disorders such as Crohn’s disease, [1,2] peptic ulcers, and esophageal cancer [3] during their lifetime [4,5]. Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for the development of peptic ulcers, delay in healing ulcers and an increase in the rate of recurrence [2]. The numerous known effects of smoking that could contribute to these include [4,6]:

- Inhibition of duodenal mucosal bicarbonate secretion, mucosal prostaglandin production, and pancreatic secretion of bicarbonate.

- Hydrochloric acid hypersecretion.

- Increase in the emptying of gastric liquids.

- Decrease in the mucosal blood flow.

- Promotion of the duodenogastric reflux.

The mucosa of the stomach is known to secrete bicarbonate and hydrochloric acid [7]. About 10-55% of that secreted acid is neutralized by the gastric bicarbonate [1,3]. To the best of our knowledge, there are very limited reports or findings documented on the effect of smoking on gastric bicarbonate secretion. We came across many studies which suggest that sucralfate stimulates the secretion of gastric bicarbonate in patients with duodenal ulcers [6-10]. We decided to carry out our own study to find out if this fact might be one of the reasons why the drug overcomes the antagonistic effect of cigarette smoking in patients with duodenal ulcers.

We observed the effect of cigarette smoke on gastric bicarbonate secretion in 14 healthy smokers and 11 healthy age and sex-matched non-smoker volunteers. The smokers were permitted to smoke as per their daily routine. We also asked them to smoke two cigarettes before the one-hour collection of gastric secretions in a fasting state. Next, the volunteers were advised to expectorate their saliva during the study. If for some reason the collection of saliva included any amount of bile, these were discarded, and the study was repeated for accurate results.

The bicarbonate secretion rate of the stomach was predicted with the aid of a two-component model:

- Gastric juice volume.

- H+ concentration and osmolality of gastric juice and plasma [7].

The mean gastric bicarbonate secretion recorded during the study was 0.78 to 0.16mmol/h in smokers and 4.25 to 1.08mmol/h in non-smokers (p<0.01). The outcome of the study suggested that smokers produced low gastric bicarbonate secretions as compared to non-smokers. This fact explains why the adverse effect of smoking is detected in patients with duodenal ulcer. Similarly, the reported beneficial effect of sucralfate therapy in patients with duodenal ulcer who continue smoking [8], could be attributed to this mechanism. However, a larger and more extensive study is necessary to validate our investigation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Diagram listing different gastrointestinal disorders caused by cigarette use.

References

- Zhang L, Ren JW, Wong CC, Wu WK, Ren SX, et al. (2012) Effects of cigarette smoke and its active components on ulcer formation and healing in the gastrointestinal mucosa. Curr Med Chem 19(1): 63-69.

- Garrow D, Delegge MH (1993) Risk factors for gastrointestinal ulcer disease in the US population. Dig Dis Sci 55(1): 66-72.

- Hecht SS (2003) Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 3(10): 733-744.

- Li LF, Chan RL, Lu L, Shen J, Zhang L, et al. (2014) Cigarette smoking and gastrointestinal diseases: The causal relationship and underlying molecular mechanisms (Review). International Journal of Molecular Medicine 34(2): 372-380.

- Berkowitz L, Schultz BM, Salazar GA, Pardo RC, Sebastián VP et al. (2018) Impact of cigarette smoking on the gastrointestinal tract inflammation: Opposing effects in crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Frontiers in Immunology 9: 74.

- Ainsworth MA, Hogan DI, Koss MA, Isenber JI (2010) Cigarette smoking inhibits acid-stimulated duodenal mucosal bicarbonate secretion. Ann Intern Med 119(9): 882-886.

- Shin VY, Cho CH (2005) Nicotine and gastric cancer. Alcohol 35(3): 259-264.

- Lunney PC, Leong RW (2012) Ulcerative colitis, smoking and nicotine therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 36(11-12): 997-1008.

- Feidman M (1983) Gastric bicarbonate secretion in humans. Effect of pentagastrin, bethanechol and 11, 16, 16-trimethyl prostaglandin- E2. J Clin Invest 72(1): 295-303.

- Lam SK, Hui WM, Lau WY, Branicki FJ, Lai CL, et al. (1998) Sucralfate overcomes adverse effect of cigarette smoking on duodenal ulcer heling and prolongs subsequent remission. Gastroenterology 92(5 Pt): 1193-1201.

© 2020 Faiza Ahmed. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)