- Submissions

Full Text

Gastroenterology Medicine & Research

Transesophageal EUS-Guided Pseudocyst Drainage: Is the Juice Worth the Squeeze?

Joshua B French MD1, Swati Pawa MD1 Raymond B Dyer MD2 and Rishi Pawa MD1*

1Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston Salem, NC, USA

2Department of Radiology, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston Salem, NC, USA

*Corresponding author:Rishi Pawa MD, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, USA

Submission: November 27, 2019;Published: December 06, 2019

ISSN 2637-7632Volume4 Issue2

Abstract

Acute pancreatitis is a common gastrointestinal complaint that can lead to both acute and chronic symptoms. One such complication is the development of peripancreatic fluid collections that can become symptomatic and thus require drainage. The mainstay of drainage previously was handled mostly by surgical intervention but over the past several years the paradigm for drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections has shifted to favor more minimally invasive techniques, such as Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) guided drainage. While EUS-guided drainage of these peripancreatic fluid collections in a trans gastric or trans duodenal manner has been well documented, not all collections are amenable to these lumens. Transesophageal drainage has been described for drainage of superior abdominal and mediastinal fluid collections. More recently the development of a lumen apposing, fully covered, self-expanding metal stent (laSEMS) has been used for drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections with a report of successful use via a transesophageal approach. In our case we present the first successful use of a 15mmx10mm electrocautery enhanced laSEMS to drain a sub-diaphragmatic peripancreatic fluid collection via a transesophageal approach.

Keywords: Pancreatic pseudocyst; Transesophageal; Lumen-apposing fully covered self-expanding metal stent; EUS-guided drainage

Introduction

Acute Pancreatitis is one of the leading gastrointestinal causes of hospitalization in the United States with an associated 2.6billion dollars per year of inpatient costs [1]. While the majority of cases are associated with a self-limited interstitial edematous pattern of inflammation that resolves over the course of days, occasionally pancreatitis can lead to further complications. One such complication is the development of peripancreatic fluid collections such as pseudocysts or walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN), depending on the pattern of injury [2]. While some of these peripancreatic fluid collections resolve spontaneously, some can become chronic and lead to ongoing abdominal pain, early satiety, duodenal obstruction, or vascular occlusion. Therefore, in the setting of symptomatic fluid collections drainage, is typically pursued.

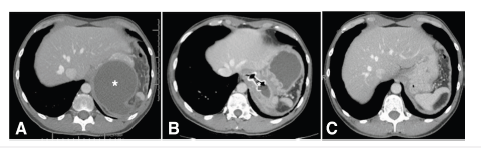

In the past, the mainstay of drainage of symptomatic peripancreatic fluid collections, specifically WOPN, was performed via open surgical necrosectomy [3,4]. However, in the past several years multiple studies have suggested and demonstrated that less invasive methods of drainage, including endoscopic drainage methods, have some advantages over an open surgical necrosectomy [5,6]. Accordingly, over the last several years the paradigm regarding the therapeutic approach to WOPN, infected necrosis, and pancreatic fluid collections has shifted more towards initial therapy with minimally invasive techniques prior to surgical intervention in appropriate patients (Figure 1).

While minimally invasive drainage techniques, such as EUS-guided necrosectomy, can be beneficial in the correct patient population, limitations do exist. One such limitation is the location of the fluid collection within the abdomen. Due to the variability in which these collections form, not all collections can be adequately or safely reached by endoscopic methods due to the collection’s relative location adjacent to the GI tract. However, as endoscopic methods, particularly those of endoscopic ultrasound guidance, and equipment have improved over time, some fluid collections that were previously felt to be not amenable to endoscopic drainage can now be considered. We present a case of acute pancreatitis complicated by WOPN that was located very superiorly in the abdomen and was successfully drained using a lumen-apposing, fully covered, self-expandable metal stent (laSEMS) that was placed via a transesophageal approach.

Figure 1:CT scan images of the abdomen demonstrating. [A] initial PFC (Marked with an*), [B] laSEMS in position with the flange in the esophageal lumen and the distal flange within the PFC (Stent marked with an*), and [C] 5 weeks after the removal of the laSEMS demonstrating resolution of the PFC.

Case Report

A 42-year-old male with a history of hypertension, gout, and recurrent acute pancreatitis secondary to alcohol abuse, presented to our GI clinic to establish care regarding pancreatitis complicated by development of pseudocyst. Over the past year, he had multiple admissions in the hospital for acute pancreatitis. The most recent episode was approximately 6 weeks prior to our initial consultation where he was hospitalized at an outside facility for acute pancreatitis and underwent Computed Topography (CT) scan that demonstrated a 12.8cm x 8.5cm peripancreatic fluid collection. At his initial clinic visit he complained of ongoing left upper quadrant abdominal pain that radiated to his back and was associated with some intermittent nausea. His initial laboratory evaluation did not reveal any significant abnormalities (normal Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferase, Lipase, and Amylase.) A repeat CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast (pancreas protocol) was obtained which demonstrated a 10cm x 8.4cm x 7.2cm sub diaphragmatic, retro gastric, low-attenuation, relatively thin walled, well-circumscribed peripherally enhancing peripancreatic and peri splenic fluid collection most likely representing a pseudocyst. The fluid collection was abutting the gastric fundus. Given his ongoing symptoms, options regarding drainage were discussed with the patient and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided endoscopic drainage was pursued (Figure 2).

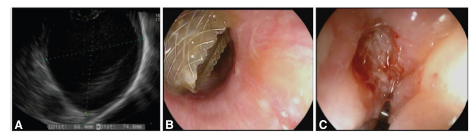

Figure 2:[A] An EUS image of the fluid collection, [B] Endoscopic view of the proximal flange of the laSEMS deployed in the distal esophagus, and [C] an endoscopic view of the distal esophagus after removal of the laSEMS.

The following week, EUS was performed using a linear echoendoscope at 7.5MHz frequency. An 8.1cm X 9.8cm discrete anechoic lesion, consistent with a pseudocyst was noted adjacent to the tail of the pancreas, in close apposition with the gastric fundus. Given the location of the pseudocyst abutting the gastric fundus, a transgastric drainage was not feasible. Under EUS guidance, a 15mm x 10mm electrocautery enhanced laSEMS was placed in the pseudocyst via trans esophageal approach (2cm proximal to the GE junction). Thick brown fluid was seen draining from the stent post-procedure. Following this, the EUS scope was switched with a forward viewing gastroscope and advanced through the stent into the cavity where there was scant necrotic material adherent to the cavity wall. He was admitted to the hospital for observation overnight.

The following day, he had improvement in his overall symptoms and a repeat CT abdomen and pelvis was obtained which demonstrated the transesophageal stent in good position with a decrease in the overall size of the fluid collection to 7cm x 5.5cm x 4.5cm. He was subsequently discharged and followed up in Gastroenterology clinic in 4 weeks with a repeat pancreas protocol CT that demonstrated complete resolution of pseudocyst. An upper endoscopy was performed and the laSEMS was removed with a snare. He continued to remain symptom free and a follow-up pancreas protocol CT was obtained a year later, which did not show any new peripancreatic fluid collections.

Discussion

EUS-guided necrosectomy and peripancreatic fluid drainage has become an accepted, if not the preferred, means of initial attempt at therapeutic drainage. By using ultrasound guidance, one is able to visualize most peripancreatic fluid collections and determine the accessibility of the collections to endoscopic ultrasound guided drainage. While most collections can be drained in a trans gastric or trans duodenal approach, occasionally a fluid collection is located or oriented in such a way that drainage into these lumens is not feasible. In such cases where peripancreatic fluid collections are located superiorly in the abdomen, a transesophageal approach to drainage is sometimes possible but has been less studied.

In 2000, Baron et al. [7] first described a case of a pancreatic pseudocyst drained by EUS-guided placement of a plastic stent placed via a transesophageal approach. Similarly, case reports of mediastinal fluid collection drainage by EUS-guidance via transhiatal and transesophageal approaches have also been described, some with placement of plastic stents to facilitate drainage [8-10]. Eventually, small case series went on to describe similar successful results of peripancreatic pseudocyst drainage either in the superior aspect of the abdomen or within the mediastinum with aspiration or plastic stent placement [11,12]. While fluid collections appeared to be well drained several adverse events were noted with transesophageal drainage in these reports, including: Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and mediastinitis. More recently, Gornals et al. [13] has described the use of a lumen-apposing, fully covered, self-expanding metal stent (laSEMS) for transesophageal drainage of a peripancreatic fluid collection. In this report, a 10mm x 10mm laSEMS was used and the procedure was complicated by a pneumothorax although a note was made that it was felt this was due to orotracheal positive pressure [13]. In our case, we described the successful use of a 15mm x 10mm electrocautery enhanced laSEMS to drain a subdiaphragmatic peripancreatic fluid collection via a transesophageal approach, which resulted in resolution of the fluid collection without complications. The theoretical benefits of using a laSEMS stent is the decreased risk of stent migration, larger diameter of stent to allow for effective drainage and a route for endoscopic necrosectomy if necessary, decreased risk of complications due to the stent being fully covered and lumen-apposing, decreased number of procedures for re-intervention, and decreased overall procedure length due to the method of placing an electrocautery enhanced stent device. However, more studies will need to be completed to see if transesophageal drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections demonstrates these benefits and has a comparable safety profile to its more common usage in trans gastric and trans duodenal drainage techniques.

References

- Peery AF, Dillon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE (2012) Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology 143(5): 1179-1187.

- Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, et al. (2013) Classification of acute pancreatitis-2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by International consensus. Gut 62: 102-111.

- Beger HG, Büchler M, Bittner R, Oettinger W, Block S, et al. (1988) Necrosectomy and postoperative local lavage in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis: Results of a prospective clinical trial. World J Surg 12(2): 255-262.

- Hartwig W, Werner J, Müller CA, Uhl W, Büchler MW (2002) Surgical Management of severe pancreatitis including sterile necrosis. Journal of Hepato-biliary-pancreatic Surgery 9(4): 429- 435.

- Van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, et al. (2010) A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 362(16): 1491-1502.

- Bakker OJ, Van Santvoort HC, Van Brunschot S, Geskus RB, Besselink MG, et al. (2012) Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: A randomized trial. JAMA 307(10): 1053-1061.

- Baron TH, Wiersema MJ (2000) EUS-guided transesophageal pancreatic pseudocyst drainage. Gastrointest Endosc 52(4): 545-549.

- Mohl W, Moser C, Kramann B, Zeuzem S, Stallmach A (2004) Endoscopic transhiatal drainage of a mediastinal pancreatic pseudocyst. Endoscopy 36(5): 467.

- Săftoiu A, Ciurea T, Dumitrescu D, Stoica Z (2006) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transesophageal drainage of a mediastinal pancreatic pseudocyst. Endoscopy 38(5): 538-539.

- Gupta R, Munoz JC, Garg P, Masri G, Nahman NS, et al. (2007) Mediastinal pancreatic pseudocyst-a case report and review of the literature. Med Gen Med 9(2): 8.

- Trevino JM, Christein JD, Varadarajulu S (2009) EUS-guided transesophageal drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc 70(4): 793-797.

- Piraka C, Shah RJ, Fukami N, Chathadi KV, Chen YK (2009) EUS-guided transesophageal, transgastric, and transcolonic drainage of intra-abdominal fluid collections and abscesses. Gastrointest Endosc 70(4): 786-792.

- Gornals JB, Loras C, Mast R, Botargues JM, Busquets J, et al. (2012) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transesophageal drainage of a mediastinal pancreatic pseudocyst using a novel lumen-apposing metal stent. Endoscopy doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309384.

© 2019 Álvaro Zamudio Tiburcio. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)