- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

Incidence of Urinary Tract Infection in Catheterised Geriatric Patients in a Tertiary Care Centre in North India

Bhasker S1*, Mitra S2, Komala S3 and Sharma V4

1M D Medicine, Trained in Geriatrics (AIIMS, New Delhi) Department of Medicine, Military Hospital, India

2M D Medicine, Department of Medicine, Military Hospital, India

3DNB GI Surgery, M S Surgery, Department of Surgery, India

4Classified Spl Dermatology, MD Dermatology, India

*Corresponding author:Sumit Bhasker, MD Medicine, Trained in Geriatrics, Department of Medicine, Military Hospital, Jalandhar, Punjab, India

Submission: January 24, 2023; Published: March 08, 2023

ISSN 2578-0093Volume8 Issue3

Abstract

Background

Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) are the most common cause of Hospitalacquired

infection affecting about 150 million individuals annually worldwide. UTIs are grouped into

uncomplicated and complicated infections especially in elderly patients. Data on CAUTIs in geriatric age

group in hospital are very less. This study was done to elucidate the causative factors for CAUTIs and

related outcomes (in terms of length of stay and mortality), in geriatric patients (>65yrs) admitted to a

tertiary care hospital in Northern India.

Methods

A prospective study was conducted on consecutive 100 patients who had undergone urinary bladder

catheterization from period between 01 Jul 2020 to 01 Jul 2021 at tertiary care service hospital in

Jalandhar, Punjab, India. All Geriatric patients (>65yrs age) who presented to the hospital were included

in the study. Written informed consent was taken from all the included patients.

Results

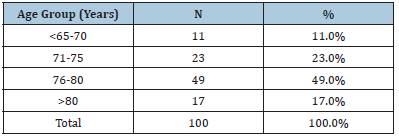

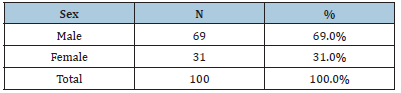

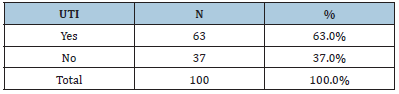

Mean age of study subjects in present study was 76.3 years with 69% male and 31% female subjects.

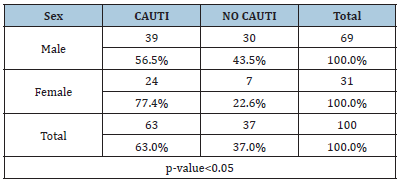

The incidence of UTI among catheterized patients was 63%. The incidence of CAUTI was much higher in

women than in men which is in consonance with other studies. In our study about three fourths (77.6%)

catheterized patients with more than 7 days duration developed UTI. In the present study almost half

(52.4%) of the patients developed bacteriuria within the first week while 87.3% developed bacteriuria

within 2 weeks. Symptomatic UTI was observed in 51.9% episodes where fever was the most observed

symptom (81.5%) followed by pain (50%).

Conclusion

Modifiable risk factors should be addressed adequately and prevent avoidable catheterization to reduce

incidence of UTI.

Keywords: CAUTI; Complicated UTI; Catheterization in elderly; Infection

Abbreviations:CAUTI: Catheter Acquired Urinary Tract Infection; UTI: Urinary Tract Infections

Introduction

Catheter Acquired Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) is one of the most common health cares acquired infections affecting about 150 million individuals annually worldwide [1]. Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) are grouped into uncomplicated and complicated infections [2]. Uncomplicated UTIs occur in immuno-competent females, with no history of urinary tract manipulation or structural abnormalities in the urinary tract. Complicated UTIs occur in the presence of a structural or functional abnormality like patients with urinary tract obstruction or urinary retention (due to neurological disease-paraplegia etc.), immuno-compromised state, pregnancy, or those with an indwelling foreign body such as a stone, ureteral stent, or urinary catheter. UTIs in men are considered complicated (shorter urethra length, antibacterial prostatic secretions act as natural barriers against infection). In 2011, there were an estimated 93 000 cases of CAUTI in United States acute care hospitals [3] making it the most common nosocomial infection leading to increased duration of hospitalization, antibiotics misuse/overuse and great financial burden. Well known risk factors for CAUTI are age, female sex, diabetes, and prolonged catheterization time. CAUTIs can lead to devastating complications such as sepsis and MODS, and an estimated 13,000 deaths each year can be attributed to healthcare associated UTIs [4]. About 70-80% of these infections are attributable to use of an indwelling urethral catheter. Almost 69% of these are avoidable [5]. The measure proven to be effective in reducing CAUTI rates can be summarized as avoiding unnecessary catheterization, reducing duration of catheterization (depending upon necessity and risk vs benefits), maintaining asepsis for insertion and using hydrophilic-coated catheters [6,7]. Indwelling urinary catheters are generally considered to be short term if they are in situ for less than 30 days and chronic or long term when in situ for 30 days or more [8]. Indwelling catheter use in acute care facilities is usually short term, while chronic catheters are most common for residents of long-term care facilities. The daily risk of acquisition of bacteriuria with an indwelling catheter is 3-7%. The rate of acquisition is higher for women and older persons Bacteriuria is universal once a catheter remains in place for several weeks. Patients with chronic indwelling catheters are assumed to be continuously bacteriuric. Clinical and microbiologic considerations may vary for short- and long-term catheters. Urinary catheter acquired infection is usually manifested as asymptomatic bacteriuria (CA-ASB). The term Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) is defined as UTI in an individual whose urinary bladder is catheterized within the past 48 hours leading to a symptomatic infection (symptoms may include-fever, suprapubic tenderness, costovertebral angle tenderness, urinary frequency or urgency or dysuria) urine culture with more than 105CFU/mL of one bacterial species [9] (non-bacterial pathogens have been excluded since 2015). For a short-term indwelling catheter, the frequency of infection is directly related to the duration of catheterization. Men have a somewhat lower incidence than women. Approximately 80% of hospitalized patients with an indwelling catheter receive antimicrobial therapy for some indication [10]. Around 60- 80% of hospitalized patients with an indwelling catheter receive antimicrobials, usually for indications other than urinary tract infection. If a patient is receiving antimicrobial therapy, onset of bacteriuria is delayed. During the initial 4 days of catheterization, concomitant antimicrobial therapy is associated with a decreased rate of infection. The short-term risk of acquiring infection is increased when the urethral meatus is colonized by potential uropathogens. After 4 days the infection rate is similar, whether or not antimicrobials are continued, but more resistant organisms are isolated from patients receiving antimicrobials [10]. For persons with long term indwelling catheters, the incidence of new infection is similar to that with short-term catheterization; approximately 3-10% will contract a new infecting organism every day [11]. These organisms usually replace previously infected organisms or become an additional organism in poly-microbial infection. The most common infecting organism is Escherichia coli [12]. Other Enterobacteriaceae as well as Enterococci spp, coagulase negative Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, other non-fermenters, and Candida spp are also frequently isolated.

UTI is the second most common infection in the geriatric population [13]. Furthermore, urine and faecal incontinence, dehydration, impaired cognitive function, and limited activity increase their susceptibility to infections. Moreover, atypical symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, respiratory distress and altered sensorium) can cause delays in the diagnosis [14]. Data on CAUTIs in geriatric age group patients admitted in hospital are very less especially from the Indian subcontinent. This study was done to elucidate the causative factors for CAUTIs and related outcomes (in terms of length of stay and mortality), in geriatric patients (>65yrs) admitted to a tertiary care hospital in Northern India.

Materials & Methods

The present study was conducted to study the Incidence of urinary tract infections in catheterized geriatric patients.

Study area and study period

The study was conducted at Military hospital Jalandhar. The study was done for a period of one year from 1 Jul 2020 to 01 Jul 2021. The study commenced after due approval from the hospital ethics committee.

Inclusion criteria

a. All patients >65yrs of age willing to participate in study, catheterized after admission in the hospital.

Exclusion criteria

a. Patients unwilling to participate in the study.

b. Patients who have been catheterized prior to

hospitalization.

c. Patients on treatment for urinary tract infection prior to

hospitalization.

d. Patients less than 65 years of age were not included in the

study.

e. Patients with preexisting structural abnormalities in

urinary tract/strictures/high grade BPH/Obstructive uropathy

and CKD patients were also excluded.

f. Patients with dementia are unable to give informed

consent.

Study design

Hospital based prospective observational study.

Sampling technique and sample size

Consecutive types of non-probability sampling were used for selection of study subjects. All the catheterized geriatric patients fulfilling eligibility criteria were included in the study after taking informed consent. The final sample size was 100 patients.

Methodology

All the admitted catheterized geriatric patients were first subjected to urine examination for albumin, sugar, blood, pus cells, and blood and urine culture. Catheters were routinely changed after 2 or more weeks or changed when there are clinical complaints of fever, dysuria, cloudy urine, blockage, or other symptoms of urinary tract infections. Urine culture was done on the 2nd day post catheterization followed by thrice a week thereafter till 1 week after the catheter had been removed. Blood examination comprised of Hb, TLC, DLC, ESR, S. urea, S. creatinine and blood sugar was done. Information regarding duration of catheterization, clinical features, diagnosis, etc. was recorded on a specially designed proforma.

Statistical analysis

All the collected data was entered into the Microsoft Excel sheet and then transferred to SPSS software ver. 17 for analysis. Appropriate statistical tests were applied based on type and distribution of data. P-value <0.05 was taken as a level of significance.

Results

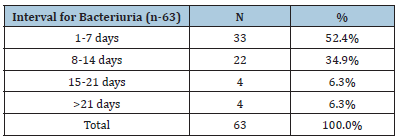

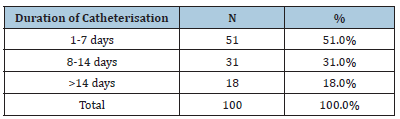

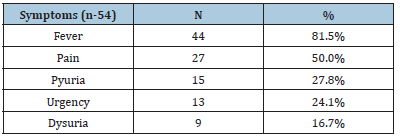

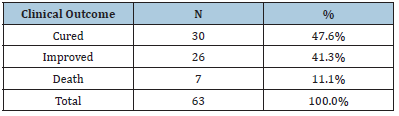

The Incidence of UTI among catheterized patients was 63%. Over three fourth (77.4%) of the females with catheters developed UTI while 56.5% of catheterized males developed UTI (Tables 1-4). A significant association was observed between female gender and development of UTI in patients (p<0.05). About half (52.4%) of the patients developed bacteriuria within 7 days while 87.3% developed bacteriuria within 2 weeks. About three fourth (77.6%) catheterized patients with more than 7 days duration developed UTI. Fever was the most commonly observed symptom (81.5%) followed by pain (50%), pyuria (27.8%), urgency (24.1%) and dysuria (16.75). Out of the total patients, 41.3% patients improved, 47.6% were bacteriologically cured while 7 (11.1%) patients died. Most of the organisms showed sensitivity towards Tigicyclin followed by Colistin and Magnex, while maximum resistance was observed for cephalosporin’s followed by Nitrofurantoin and Amikacin (Tables 5-8).

Table 1:Distribution of subjects based on age groups.

Table 2:Distribution of subjects based on gender.

Table 3:Distribution of subjects based on development of UTI

Table 4:Association of gender with development of UTI.

Table 5:Distribution of subjects based on interval for bacteriuria.

Table 6:Distribution of subjects based on duration of catheterization.

Table 7:Distribution of subjects based on symptoms

Table 8:Distribution of subjects based on clinical outcome.

Discussion

A hospital based prospective observational study was conducted with the aim of studying the Incidence of UTI in catheterized Geriatric patients. It comes a close second to respiratory infections among hospitalized patients and community-dwelling adults more than 65 years of age [15]. The mean age of study subjects in present study was 76.3 years with 69% male and 31% female subjects. The incidence of UTI among catheterized patients was 63%. In the study by Tambyah PA et al. [16] the incidence of CAUTI was found to be 14.9% and the incidence of CAUTI was much higher in women (23.2%) than in men [16] (8.9%) which is in consonance with our study. The incidence of UTI is higher in women compared with men across all age groups. Over 10% of women older than 65 years of age reported having a UTI within the past 12 months. This number increases to almost 30% in women over the age of 85 years [17,18]. In both men and women over the age of 85 years, the incidence of UTI increases substantially. A small cohort study in this age group found the incidence of UTI in women to be 0.13 per person-year and 0.08 per person-year in men [19]. Age-associated changes in immune function, exposure to nosocomial pathogens and an increasing number of comorbidities put the elderly at an increased risk for developing infection [20]. Catheter-associated bacteriuria is the most common infection in both hospitals and long-term care facilities [21]. In a study by Letica-Kriegel AS et al. [22] it was found that approximately 12% of patients who have a catheter inserted for 30 days developed CAUTI [22]. In our study about three fourths (77.6%) catheterized patients with more than 7 days duration developed UTI. In the present study almost half (52.4%) of the patients developed bacteriuria within the first week while 87.3% developed bacteriuria within 2 weeks. Symptomatic UTI was observed in 51.9% episodes where fever was the most commonly observed symptom (81.5%) followed by pain (50%).

Conclusion

Development of prevention strategies, including aseptic insertion of urinary catheters, minimizing use of catheters and minimizing duration of catheter use, has led to a decrease in the incidence of CAUTI [23]. As our population ages, the burden of UTI in older adults is expected to grow, making the need for improvement in diagnostic, management and prevention strategies critical to improving the health of older adults. These will also aid in improving antibiotic accuracy and stewardship.

References

- Stamm WE, Norrby SR (2001) Urinary tract infections: Disease panorama and challenges. J Infect Dis 183(1): S1-S4.

- Mireles ALF, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ (2015) Urinary tract infections: Epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol 13(5): 269-284.

- Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, et al. (2014) Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med 370(13): 1198-1208.

- Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, et al. (2007) Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep 122(2): 160-166.

- Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, Rogers MAM, Ratz D, et al. (2016) A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med 374(22): 2111-2119.

- Nicolle LE, Coffin SE, Maragakis LL, Meddings J, Pegues DA, et al. (2014) Strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 35(5): 464-479.

- Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA, et al. (2010) Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31(4): 319-326.

- Rudman D, Hontanosas A, Cohen Z, Mattson DE (1988) Clinical correlates of bacteremia in a veterans administration extended care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc 36(8): 726-732.

- Mobley HLT, Warren JW (1987) Urease-positive bacteriuria and obstruction of long-term urinary catheters. J Clin Microbiol 25(11): 2216-2217.

- Mobley HLT, Hausinger RP (1989) Microbial ureases: Significance, regulation, and molecular characterization. Microbiol Rev 53(1): 85-108.

- Warren JW, Muncie HL, Craggs MH (1988) Acute pyelonephritis associated with the bacteriuria of long-term catheterization: A prospective clinico-pathological study. J Infect Dis 158(6): 1341-1346.

- Kucheria R, Dasgupta P, Sacks SH, Khan MS, Sheerin NS (2005) Urinary tract infections: New insights into a common problem. Postgrad Med J 81(952): 83-86.

- Pawelec G (2006) Immunity and ageing in man. Exp Gerontol 41(12): 1239-1242.

- Tanyel E, Fisgin NT, Tulek N, Leblebicioglu H (2006) The evaluation of urinary infections in elderly patients. Turk J Infect 20(2): 87-91.

- Tsan L, Langberg R, Davis C, Phillips Y, Pierce J, et al. (2010) Nursing home-associated infections in department of veterans affairs community living centers. Am J Infect Control 38(6): 461-466.

- Tambyah PA, Maki DG (2000) Catheter-associated urinary tract infection is rarely symptomatic: A prospective study of 1497 catheterized patients. Arch Intern Med 160(5): 678-682.

- Foxman B, Barlow R, D’arcy H, Gillespie B, Sobel JD (2000) Urinary tract infection: Self-reported incidence and associated costs. Ann Epidemiol 10(8): 509-515.

- Eriksson I, Gustafson Y, Fagerstrom L, Olofsson B (2010) Prevalence and factors associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs) in very old women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 50(2): 132-135.

- Caljouw MA, Den Elzen WP, Cools HJ, Gussekloo J (2011) Predictive factors of urinary tract infections among the oldest old in the general population, a population-based prospective follow-up study. BMC Med 9: 57.

- Mehta MJ, Quagliarello VJ (2010) Infectious diseases in the nursing home setting: Challenges and opportunities for clinical investigation. Clin Infect Dis 51(8): 931-936.

- Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, et al. (2010) Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 50(5): 625-663.

- Kriegel ASL, Salmasian H, Vawdrey DK, Youngerman BE, Green RA, et al. (2019) Identifying the risk factors for catheter-associated urinary tract infections: A large cross-sectional study of six hospitals. BMJ Open 9.

- Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA (2010) Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory C Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31(4): 319-326.

© 2023 Bhasker S. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)