- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

A Status Epilepticus Revealing Severe Chronic Theophylline Toxicity in an Elderly Patient at Emergency Department: Case Report

Yahia Yosra*1, Maghraoui Hamida1, Trabelsi Insaf2, Rezgui Emna1, Kilani Mohamed3, Guissouma Jihène2 and Majed Kamel1

1Emergency Department of La Rabta Teaching Hospital, Tunisia

2Intensive Care Unit of Bizerte Teaching Hospital, Tunisia

3Emergency Department of the Emergency and Toxicology Medical Center, Tunisia

*Corresponding author:Yahia Yosra, Emergency Department of La Rabta Teaching Hospital, Tunisia

Submission: April 08, 2022; Published: April 27, 2022

ISSN 2578-0093Volume7 Issue4

Abstract

Theophylline toxicity is associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality. The use of this molecule as a long-term broncho dilatator during asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease remains quite common despite its narrow therapeutic margin and its related toxicity. The utilization patterns of Theophylline are not well described while noting a more frequent prescription in low-to-middle income countries. This exposes to an increased risk of intoxication and iatrogenic especially in the elderly who are more likely to develop clinical manifestations of Theophylline toxicity. Elderly patients are thus exposed to a higher risk of organ impairments and of drug interaction that may affect Theophylline clearance and lead to overdose. Otherwise, the management of these patients may be difficult due to more frequent comorbidities. We report the case of an elderly patient admitted to the emergency department in status epilepticus revealing severe chronic Theophylline toxicity.

Keywords: Theophylline; Intoxication; Chronic toxicity; Elderly; Iatrogenia; Emergency department

Abbreviations: COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; SVT: Supraventricular Tachycardia

Introduction

Theophylline is a drug belonging to the family of xanthine’s commonly used to treat various respiratory conditions with airways obstruction, such as asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) [1]. In these situations, precisely, Theophylline can be indicated as a second-line bronchodilator treatment, but its use has significantly decreased throughout the years, mainly due to the arrival of new molecules with similar effects and to the related toxic risk of theophylline [1-3]. However, this drug remains still prescribed despite its narrow therapeutic margin with utilization patterns not well-described [3,4]. We observe also a more common prescription in low-to-middle income countries due to its low cost [5]. The pharmacokinetic properties of theophylline largely explain its clinical toxic effects which can occur by intentional overdose but also when metabolism or clearance of theophylline is altered due to certain physiological stressors [6]. These phenomena are all the more observable in the elderly population where the frequent prescription of drug combinations can increase the risk of drug interaction. Moreover, the impairment of liver and/or kidney function with aging, can slow down the theophylline clearance and therefore, its elimination from the body [7,8]. We report the case of a patient hospitalized in an emergency department for a convulsive status epilepticus related to a Theophylline poisoning.

Case Presentation

AM is 68-year-old male patient with a history of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), on an inhaled short-acting mimetic beta 2, inhaled corticoids and theophylline, was found unconscious at his workplace on the day of admission with foam on his lips. Initial examination objectified unconscious agitation with no signs of neurologic localization or meningeal syndrome; pupils were in a reflective intermediate position with a capillary glucose level of 2,06g/dl in a context of apyrexia. The respiratory examination showed polypnea at 22cpm with no signs of respiratory exhaustion, a normal pulmonary auscultation and an Oxygen pulsed saturation of 96% at ambient air; The patient was tachycardic at 140bpm with blood pressure at 150/60mmHg, and with arrhythmia upon cardiac auscultation. The rest of the physical exam was without other abnormalities. The evolution was marked by the occurrence of a generalized 30-second tonic-clonic seizure that ended spontaneously.

The presentation was that of a convulsive status epilepticus without any infectious syndrome or any localization signs. Immediate management was to condition the patient with Oxygen therapy, lateral safety positioning, placement of a Guedel cannula with close monitoring and intravenous administration of clonazepam (0,015mg/Kg) followed by a 40mg/Kg-loading dose of sodium Valproate. Hydration with saline solution was then conducted. On the biological assessment, the patient had no metabolic disorder explaining the convulsive status epilepticus with a natremia of 142 mmol/L and a calcemia of 98mg/L. Furthermore, there was a nonspecific inflammatory syndrome with a C Reactive Protein at 22,4 mg/L and white blood cells count at 18480K per μL.

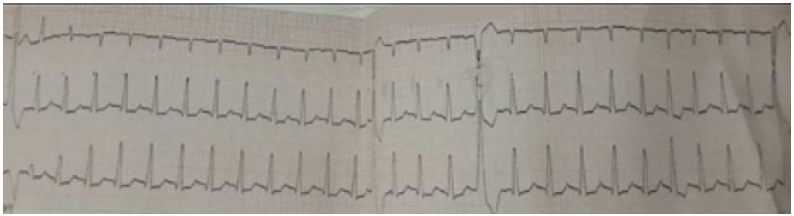

The Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) according to CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation was about 88mL/min/1.73m2, traducing a mild decline in kidney function. The kaliemia was at 3,7mmoles/L and the hepatic tests (transaminases and bilirubin) were normal. A severe hyper lactic metabolic acidosis was objectified on blood gas with a pH of 6.99, bicarbonate at 16mmoles/L, and lactates at 12mmoles/L. There was also a respiratory acidosis with a capnia of 60mmoles/L. ECG analysis showed atrial fibrillation at 150bpm with monomorphic ventricular extrasystoles (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Electrocardiogram of the patient showing tachyarrhythmia with monomorphic extrasystoles.

The injected cerebral CT was without abnormality. Theophylline Mia was 30mcg/mL (usual values: 5-20mcg/mL). Potassium supplementation was undertaken considering a lowered corrected kaliemia and associated with magnesium sulfate in the saline infusions. The evolution following first care was favorable with improvement in the patient’s neurological state and gradual recovery of his consciousness. There was also no recurrence of convulsions. Nevertheless, we noted the persistence of some paroxysmal episodes of confusion and tachyarrythmia on the ECG.

The patient was transferred to a toxicology center in an intensive care unit for the continuation of his care which resulted in a total return to a state of consciousness and reduction of rhythm disorders without recourse to antiarrhythmics. He also didn’t need respiratory assistance and was discharged after 48 hours of hospitalization. The clinical presentation was related to an involuntary chronic theophylline intoxication in an elderly patient, induced by an overdose of serum theophylline despite the use of this molecule for therapeutic purposes and which was manifested by severe neurological manifestations, metabolic and cardiac disorders.

Discussion

Theophylline is 1,3-dimethylxanthin whose action involves the endogenous release of catecholamines via indirect stimulation of beta-1 and beta-2 receptors which are produced at therapeutic levels for bronchodilation, a goal in the treatment of asthma and COPD [6]. The mechanism of action of this molecule involves inhibition of phosphodiesterases, accumulation of cyclic-AMP and a competitive antagonistic effect of adenosine receptors [4,9]. This state of hyperadrenergy explains metabolic disorders, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and neurological abnormalities with theophylline toxicity [8]. This can occur when serum theophylline levels slightly surpass the therapeutic level range [6]. Indeed, therapeutic serum levels range from 10 to 20mcg/mL and theophylline toxic levels are considered to be 20mcg/mL or higher [1,9,10].

Pharmacokinetically, theophylline has a small volume of distribution at 0.5L/kg and a half-life between 8 and 10 hours [2]. This molecule is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 system and excreted by the kidneys [9]. Therefore, any agents or pathology that alters the cytochrome P450 system or renal function can have a substantial effect on theophylline levels. These considerations largely explain the potential toxicity in an elderly subject with kidney or liver failure and in the aged population that present with an iatrogenic drug interaction due to often multiple prescriptions [8]. In our case, the serum Theophylline level (30mcg/mL) was higher than the therapeutic level range. The patient had a mild decline in kidney function which could have helped slow down Theophylline clearance. Concerning drug interaction and questioning of close family members, the patient could only identify its use as a COPD inhaled treatment, which could not explain the theophylline overdose [8,11]. However, inhaled short-acting mimetic beta2 could have potentiate the adrenergic effects of theophylline [12].

The theophylline toxicity can result in various manifestations with a risk of acute and chronic iatrogenic poisoning [6]. Minor but frequent side effects include nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal reflux, restlessness, and headache which may develop even at low plasma concentrations. More severe side effects, such as severe cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, convulsions, and even death occur at higher theophylline concentrations [10]. In chronic intoxication, severe clinical manifestations such as seizures or arrhythmias occur at lower concentrations than in acute intoxications [9,10]. In the elderly, the diagnostic difficulties associated with frequent comorbidities require rigorous clinical evaluation at emergency department. Often, patients cannot give a clear history, so it is imperative to obtain a history from EMS personnel, family, friends, and witnesses [6]. In the presence of a combination of neurological manifestations, rhythm or/and metabolic disorders in a patient under theophylline such as in our case, it is fundamental to evoke the diagnosis of theophylline intoxication and more so in the elderly.

Initial treatment in the emergency department first includes non-specific measures such as anticonvulsant treatment, airway management, correction of ionic disorders and arrhythmias management. For the management of seizures due to theophylline intoxication, intravenous benzodiazepines remain the first-line treatment for theophylline-induced seizures [1,13]. Seizures not controlled with benzodiazepines should be treated with a barbiturate such as phenobarbital or pentobarbital or another suitable sedative-hypnotic such as propofol [13]. Our patient received benzodiazepines and sodium Valproate with favorable evolution.

Concerning cardiac arrhythmias, these should be managed according to advanced cardiac life support. Most patients with theophylline cardiac toxicity are successfully managed with supportive care [6]. Some experts had recommended Adenosine as a first-line therapy to reverse theophylline-induced Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT) with caution in asthma and COPD due to a risk of inducing bronchoconstriction [8]. Other anti-arrythemics can also be used such as beta 1 antagonist or negative chronotropic Calcium channel blockers [14]. For the treatment of arrhythmia, it is also essential to correct hydro electrolytic disorders especially hypokalemia often associated with theophylline toxicity. A potassium supplementation is therefore urgent in case of hypokalemia due to beta 2 mimetic effect of theophylline [8]. Other measures for resuscitation may also be applied during theophylline intoxication such as volume expansion (20ml/Kg, IV) if the patient is hypotension and in case of fluid resuscitation failure. The administration of primarily alpha agonist such as phenylephrine or norepinephrine. The administration of an adrenergic antagonist may be warranted in rare cases of refractory hypotension [13].

The other therapeutic component of theophylline intoxication is the toxic elimination by using activated charcoal (1g/kg) which is recommended in multiple doses for acute theophylline toxicity, if there are no contraindications [2,6]. Hemodialysis is another therapeutic mean for theophylline elimination and is indicated in case of severe symptoms, such as life-threatening arrhythmias, seizures and/or clinical instability. It is also indicated in acute theophylline toxicity for theophylline levels greater than 100mcg/mL or increased theophylline levels despite appropriate care and in chronic theophylline toxicity, for theophylline levels greater than 60mcg/mL in patients between the ages of 6 months to 60 years, or levels greater than 50mcg/mL in patients less than 6 months of age or greater than 60 years [2,6,8].

In our case, the patient had not received a toxic elimination treatment. Following an early symptomatic treatment at the onset of clinical manifestations including anti-convulsive treatment, the evolution was favorable without recurrence of seizures and progressive recovery of consciousness. Administration of activated charcoal was not possible in view of the initial risk of aspiration. Atrial fibrillation and ventricular extrasystoles were managed by correction of metabolic disorders with potassium supplementation and hydration. The patient did not require arrythmias. According to the literature data and despite few cases being reported, theophylline intoxication is associated with high morbidity and mortality [6]. Despite its related toxicity, this drug is still prescribed at a higher frequency in low-to-middle income countries [5]. The main key to theophylline toxicity is prevention. Healthcare providers should avoid prescribing this agent for asthma or COPD when other safer drugs are available. If the socio-economic conditions of the patients do not allow access to safer treatments, the patients should be educated on toxic risks with special attention to the elderly. Indeed, these patients must be carefully monitored by the family doctor and pulmonologist in particular for a regular evaluation of organ failure and other drug prescriptions that may alter theophylline clearance [1].

Conclusion

The diagnosis of theophylline intoxication is often a challenge in the emergency department considering the wide range of signs that can be seen and their non-specificity, especially in the elderly [6,8]. In view of the vital prognosis, it is necessary to dose the serum theophylline at the slightest clinical suspicion to establish the diagnosis and to adapt the management. The role of the health care team is to initiate rapidly the first conditioning and resuscitation measures with a specific treatment as appropriate, based on digestive and/or extra-renal toxic purification [7,8]. The prevention is the key requiring a good assessment of risk-benefit balance by the treating physician, adequate monitoring and patient education to minimize the risk due to the low therapeutic index.

References

- Jilani TN, Preuss CV, Sharma S (2022) Theophylline. Stat Pearls Publishing, Island, pp. 1-13.

- Ghannoum M, Wiegand TJ, Liu KD, Calello DP, Godin M, et al. (2015) Extracorporeal treatment for theophylline poisoning: systematic review and recommendations from the EXTRIP workgroup. Clin Toxicol 53(4): 215-229.

- Henriksen DP, Davidsen JR, Laursen CB (2018) Nationwide use of theophylline among adults-A 20-year danish drug utilisation study. Respir Med 140: 57-62.

- Greene SC, Halmer T, Carey JM, Rissmiller BJ, Musick MA (2018) Theophylline toxicity: An old poisoning for a new generation of physicians. Turk J Emerg Med 18(1): 37-39.

- Jenkins CR, Wen F, Martin A, Barnes PJ, Celli B (2021) The effect of low-dose corticosteroids and theophylline on the risk of acute exacerbations of COPD: the TASCS randomized controlled trial. Eur Respir J 57(6): 2003338.

- Journey JD, Bentley TP (2022) Theophylline toxicity. Stat Pearls Publishing, Island, pp. 1-10.

- Guihard B, Bernardo S, Gabillet L, Jenvrin J, Potel G (2009) Chronic theophylline intoxication. JEUR 22: 62-65.

- Kong A, Ghosh S, Guan C, Fries BL, Burke FW (2021) Acute on chronic theophylline toxicity in an elderly patient. Cureus 13(2): e13484.

- Monteiro J, Alves MG, Oliveira PF, Silva BM (2019) Pharmacological potential of methylxanthines: Retrospective analysis and future expectations. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 59(16): 2597-2625.

- Aggelopoulou E, Tzortzis S, Tsiourantani F, Agrios I, Lazaridis K (2018) Atrial fibrillation and shock: Unmasking theophylline toxicity. Med Princ Pract 27(4): 387-391.

- Jonkman JH, Borgström L, Boon WJ, Noord OE (1988) Theophylline-terbutaline, a steady state study on possible pharmacokinetic interactions with special reference to chronopharmacokinetic aspects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 26(3): 285-293.

- Luo Q, Peng X, Zhang H (2021) Effect of terbutaline plus doxofylline on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Transl Res 13(6): 6959-6965.

- Hoffman RJ (2011) Methylxanthines and Selective B2 Adrenergic Agonists. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA (Eds.), Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergencies. (9th edn), McGraw-Hill, USA, pp. 952-964.

- Hosseini SM, Ajmal M, Shetty R (2021) Symptomatic supraventricular tachycardia resistant to adenosine therapy in a patient with chronic theophylline use. Case Rep Cardiol, pp. 1-4.

© 2022 Yahia Yosra. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)