- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

A Case of Man-In-The-Barrel Syndrome (MIBS) Mimicking Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH)

Arman P1, Dedeoglu SE2, Soytas RB1, Erdincler DS1 and Doventas A1*

1Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, Istanbul, Turkey

2Department of Internal Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey

*Corresponding author:Doventas A, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, Istanbul, Turkey

Submission: June 26, 2020 Published: September 27, 2021

ISSN 2578-0093Volume7 Issue2

Abstract

Man-in-the-Barrel Syndrome (MIBS) is a syndrome caused by bilateral proximal dominant muscle weakness, presenting with the patient’s failure to abduct the arms and caused by different etiologic factors. In this case, MIBS which is developed secondary to the rare cervical myelomalacia will be discussed.

Introduction

MIBS was first described in 1969 [1]. It is a disease characterized by paralysis of both arms, but the cranial nerves and the motor functions of the legs are preserved. For this reason, the patient with this syndrome appears to be in the barrel. This syndrome is rare but there are no studies reporting its incidence. The most common cause of this syndrome is cerebral ischemia; also, cerebral cortex, brain stem, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system diseases may cause this [2]. Here, we present a patient with cervical myelomalacia who presented with MIBS.

Case Report

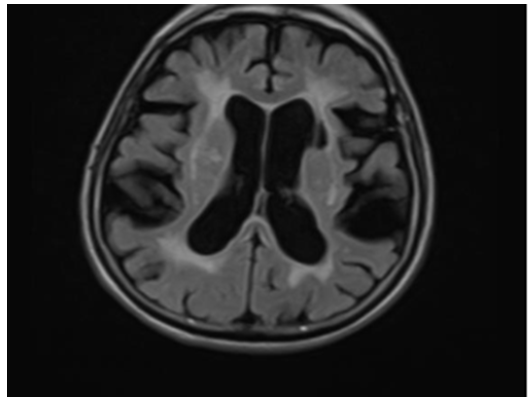

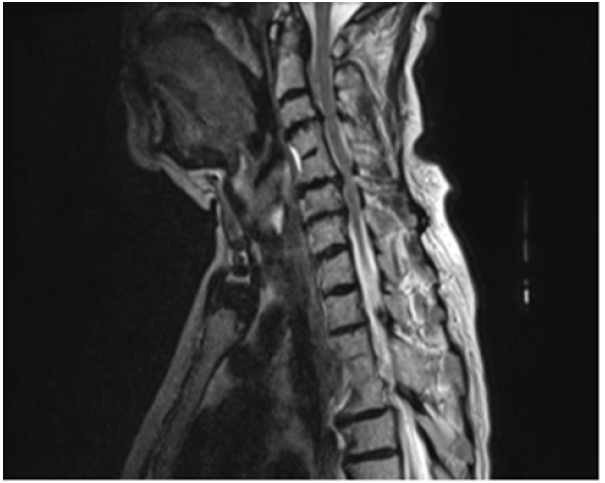

A 76-year-old woman with known hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism was admitted with complaints of increased forgetfulness, urinary incontinence and impaired balance for about 6 years. She was hospitalized with the preliminary diagnosis of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) because of the expansion of periventricular distances in radiological imaging. She was conscious and oriented but had limited cooperation. There was no sign of meningeal irritation and no nuchal rigidity. Her speech was fluent, and she had a complete understanding. Cranial nerve examination was normal. Motor system examination revealed bilateral shoulder muscle strength 3/5, elbow muscle strength 4/5 and wrist muscle strength 5/5. In other words, the patient had proximal dominant muscle weakness on the upper and lower and the appearance of the MIBS. Deep tendon reflexes were normoactive bilaterally; Hoffman sign was positive bilaterally; abdominal skin and jaw reflex were normal. The sensory system examination revealed a superficial sensory defect on the soles of the feet, the cortical sensation was normal, deep sensation in the lower extremity was decreased. Extrapyramidal and autonomic system examination was normal. The cerebellar examination was consistent with motor weakness. She had no ataxia and was spinning in 3-4 steps. Standardized mini-mental test was 22 points out of 30. The CSF dynamic MRI was consistent with small vascular disease and advanced encephalomalacia (Figure 1). On cervical MRI, C4-C5 and D4-D5 vertebrae were fusion with each other, and protrusions accompanied by dorsal osteophytes, spinal cord compression and accompanying myelomalacia were observed in C5-6 and C6-7 (Figure 2). Dementia had been attributed to chronic vascular disease. The current neurological deficit, persistent gait and balance disorder, loss of fine motor skills and bladder dysfunction were thought to be due to advanced cervical stenosis. An elective cervical laminectomy was planned, but it could not be performed due to additional comorbidities. Conservative therapy was suggested. Physical therapy was planned to preserve a range of motion of the upper extremities. Replacement therapy was given for vitamin d deficiency.

Figure 1:The CSF dynamic MRI showing small vascular disease and encephalomalacia.

Figure 2:Cervical MRI showing spinal cord compression and myelomalacia in C5-6, C6-7 and D4-5 vertebrae.

Conclusion

MIBS often occurs with damage to the areas in the bilateral frontal lobes where the upper extremities are represented somatotopic ally. This damage is often due to bilateral ischemia or infarction of the border-zone areas between the anterior cerebral artery and middle cerebral artery at the level of the motor cortex of the arm [3-5]. Therefore, these patients have generally poorer prognosis because of the accompanying neurologic findings [3]. While the involvement of the distal muscles is higher in patients with supratentorial causes; as in our case, the involvement of the proximal muscles is more related in infratentorial causes [6,7]. The distinctive features of MIBS from NPH are muscle weakness, different gait disturbance, loss of the vibration and position sense, and increased deep tendon reflexes [8,9]. In suspected cases, NPH and MBS distinction with a detailed physical examination will be very important for the patient to be guided in terms of treatment. Treatment of MIBS depends on the underlying disease. These protocols include management of the cerebrovascular diseases, hypotension and hypovolemia, malignancies or other central and peripheral nervous system disorders. Prognosis of this syndrome also varies according to the cause. Extracerebral conditions have a better prognosis than cerebral disorders [10]. On the other hand, the treatment for NPH is an implanted ventricular shunt. The overall prognosis of NPH remains poor due to comorbidities, a lack of improvement in some patients following surgery and shunt complications [11,12].

References

- Mohr JR (1969) Distal field infarction. Neurology 19: 279.

- Orsini M, Mello MP, Nascimento OJ, Reis CHM, Freitas MR (2009) Man-in-the-barrel syndrome: history and different etiologies. Rev Neurocienc 17(12): 138-40.

- Elting JW, Haaxma R, Sulter G, DeKeyser J (2000) Predicting outcome from coma: Man-in-the-barrel syndrome as potential pitfall. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 102(1): 23-25.

- Cristomo EA, Suslavich FJ (1994) Man-in-the-barrel syndrome associated with closed head injury. J Neuroimag 4(2): 116-117.

- Clerget L, Lenfant F, Roy H, Maurice G, Saleem B, et al. (2003) Man-in-the-barrel syndrome after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma 54(1): 183-186.

- Berg D, Müllges W, Koltzenburg M, Bendszus M, Reiners K (1998) Man-in-the-barrel syndrome caused by cervical spinal cord infarction. Acta Neurol Scand 97(6): 417-419.

- Pullicino P (1994) Bilateral distal upper limb amyotrophy and watershed infarcts from vertebral dissection. Stroke 25(9): 1870-1872.

- Finsterer J (2010) Man-in-the-barrel syndrome and its mimics. South Med J 103: 9-10.

- Radford NRG, Jones DT (2019) Normal pressure hydrocephalus. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 25(1): 165-186.

- Antelo MJG, Facal TL, Sánchez TP, Facal MSL, Nazabal ER (2013) Man-in-the-barrel. A case of cervical spinal cord infarction and review of the literature. The Open Neurology Journal 7: 7-10.

- Vanneste J, Augustijn P, Dirven C, Tan WF, Goedhart ZD (1992) Shunting normal‐pressure hydrocephalus: Do the benefits outweigh the risks? A multicenter study and literature review. Neurology 42(1): 54-59.

- Boon AJ, Tans JT, Delwel EJ, Egeler-Peerdeman SM, Hanlo PW, et al. (1997) Dutch normal-pressure hydrocephalus study: prediction of outcome after shunting by resistance to outflow of cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of neurosurgery 87(5): 687-693.

© 2021 Doventas A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)