- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

The Senior City & Beyond Ageing

Tigran Haas*, Cars G and Lundström MJ

Department of Urban Planning & Environment,Sweden

*Corresponding author: Tigran Haas, Department of Urban Planning & Environment, Sweden

Submission: September 04, 2020;Published: September 14, 2020

ISSN 2578-0093Volume6 Issue2

Abstract

This reflective research piece points to the need for real research on the issue of the elderly thus a need to be included in and become part of contemporary urban planning and development.Paper points to the need for more knowledge about the issues (the design and structure of public spaces, level design, location of homes in relation to commerce, service, public transport etc.) as well as the planning processes (participation/user involvement, cooperation between actors, internal municipal cooperation, etc.). Although written in a Swedish context the paper’s idea are globally grounded. It comes out of a five-year research on Ageing Society in Europe and US. One of the findings point to the fact and need that planners and architects have to become better at understanding the desires and preferences of various groups of elderly people, and those working in the healthcare services need to be involved more in the design and planning processes than ever before. Lastly all ideas have equal standing in these issues, so all designs and suggestions that work in that matter.

Keywords: Ageing society; Elderly questions; Housing; Intragenerational dwelling; Cooperatives; Urban planning and design; WHO; Senior city; Inclusive and universal design

Introduction

The world is facing a major demographic change, with an increasing proportion of elderly people in the population. Between 2007 and 2050, the proportion of the population over 60 years of age is expected to double, and the actual number more than triple; the number of people over 80 is expected to quadruple to almost 400 million [1]. In Sweden, the proportion of elderly people (65 and over) increased from 13.4 per cent to 19.1 per cent of the population between 1968 and 2012 [2]. Today, one in twenty Swedes (around half a million in total) is 80 or older, and by 2050 this figure is expected to closer to one in ten, or one million [3]. Issues regarding the elderly have lately received increased attention in various ways in the Swedish public debate. The access to special housing for elderly people with major care and medical needs has worsened in the past decade and many elderly people who wish to live in this way are denied due to a lack of spaces. In the media there are frequent discussions on quality and quantity in home help services, neglect in elderly care, future recruitment needs in the care of the elderly etc. There are reports from Japan on the development of robots both for the washing of elderly people and as social companions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Group of happy elderly people taking a self-photo (selfie) Creative Commons (CC).

The increased proportion of elderly people in society thus brings with it both opportunities and challenges. This requires change and innovation in all sectors and levels of society, including urban planning and development. However, research and development in Sweden has had a very strong focus on the form and function of housing. We believe that the issue needs to be broadened to include the living conditions of the elderly in their neighbourhood, city district, city and possibly even metropolitan area. This includes the design of public spaces and building structures as well as the location of homes in relation to other important functions, allowing the elderly to live active, social and independent lives. Being within walking distance of shops and services, even when using a walker, is an important aspect of a well-functioning, social and healthy everyday life for the elderly. An active life with regular engagements outside the home contributes to better health and an ability to remain living in one’s home. Many have noted that a physical environment suited to the elderly is also well-suited to all other ages [4] universal design (or design for all) is a term used in the world of architecture and design. As cities experience a demographic shift, the need for age-friendly urban planning and urban design is becoming ever more critical. The future of urban housing and mobility may just be shaped for and by the elderly in the future.

The issue of the elderly thus needs to be included in and become part of urban planning and development. We need more knowledge about the issues (the design and structure of public spaces, level design, location of homes in relation to commerce, service, public transport etc.) as well as the planning processes (participation/ user involvement, cooperation between actors, internal municipal cooperation, etc.). Planners and architects need to become better at understanding the needs and preferences of various groups of elderly people, and those working in the healthcare services need to be involved more in the design and planning processes.

Current Knowledge

“There is no guiding rationale for the inclusion of considerations of age and the consequences of an ageing population in the planning system” [5]. The Government commission “Bo bra på äldre dar” [Live well in old age] [5] included highlighting and developing issues from an urban planning and regional perspective, but the results were still largely focused on the home. Research in the area has traditionally had a design and architecture perspective focusing on the home, where accessibility has received extra attention.

Certain knowledge could be obtained from other countries. For example, the UK and USA, which have seen an increased interest in matters relating to the elderly from an urban planning and development perspective (urban design). For example, the British researchers Burton & Mitchell [6] have, from an urban design perspective, studied how aspects of the urban environment facilitate or hinder the presence of the elderly in cities. From an American perspective, both Ball [7] and Cisneros et al. [8] discuss the opportunities for creating local environments and neighbourhoods that allow for active and independent lives into old age. In an international literature review, Lui et al.[9] conclude that environmental gerontological research indicates that the design and quality of the physical environment is an important factor for allowing a good life into old age, and that urban research has found proof that the properties of neighbourhoods/districts have significant impact on the mobility, autonomy and quality of life of elderly people. It is also noted that elderly-friendly urban planning has moved on from only healthcare issues to include both “neighbourhood design and increasingly sophisticated conceptions of place” [9]. Alley et al. [10] note that increased cooperation between urban planning and services related to the care of the elderly, as well as support for the elderly in actively participating in urban planning, helps disseminate knowledge and thus living environments that facilitate independent living for the elderly.

Gilroy [11] stresses the importance of urban environments that are legible, familiar, pedestrian oriented and easily accessible in order to reduce confusion (not only among people with cognitive decline or dementia), e.g. keeping older buildings functioning as landmarks and having a variation of street frontages, as well as avoiding cul-de-sacs, will make it easier for older people. Furthermore, keeping some existing artefacts when making changes in the urban environment is important for people to keep an identity of place, especially for older people that have lived there a long time and may have strong mental attachments to the place [11,12]. The importance of creating better living conditions for the elderly has obviously also been highlighted outside of academia. In 2015 the WHO launched a global project aimed at getting cities (municipalities) to integrate issues relating to the elderly into their physical and social urban planning, in order to create “agefriendly cities”. Together with 35 cities around the world, the WHO identified a number of properties of age-friendly cities, where physical accessibility, proximity to service, security, affordability and social inclusion were important characteristics in all cities [4]. One of the project’s conclusions is that an age-friendly city is a city which encourages and facilitates active ageing, i.e., optimizes the opportunities for good health, involvement and security in order to increase the quality of life of the elderly [13]; (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Management of living costs and meeting a safe retirement period. Photo: Garry Knight.

The WHO Global Age-Friendly Cities Network now exists to develop and disseminate knowledge and experiences, produce guidelines, follow up on development etc. Many countries now have national networks which work with cities as well as villages and rural communities. One interesting initiative is the Ageing Well Network in Ireland, whose work since 2007 has including the production of “The New Agenda on Ageing-To Make Ireland the Best Country to Grow Old In” and work on a national program for agefriendly counties. Cities that have addressed accessibility are likely to be ahead of the game in age-friendliness. Ageing population is now influencing how cities are designed, what services they offer and where people live-and these developments will continue in the future. This will particularly impact urban services, including health services and individuals’ well-being. Urban innovations are starting to challenge how ageing cities function and what they offer in services.

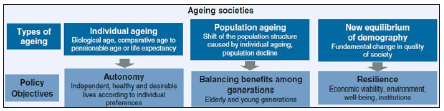

Cities simply need to accept and adapt to ageing in place, multigenerational urban setting, smart ageing and the combination of traditional and contemporary lifestyles and accessibility where the “senior silver city” generation of people cannot and must not be cut off from the rest of society, with age becoming a new form of segregation. On the contrary cities and planner need to accept that they - the ageing society - and the new reality reflect a desire for an active, experience-filled lifestyle. Three inter-related aspects of ageing must be considered in creating policy responses for ageing societies:

i) individual ageing.

ii) population ageing.

iii) the new equilibrium of societies that have undergone the different stages of an ageing trend [14,15]. [Figure 1: Ageing Societies-Types of Ageing and Policy Objectives] (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Management of living costs and meeting a safe retirement period. Photo: Garry Knight.

“Elderly”?

Including everyone who has turned 65 in the very broad category of “elderly” can be problematic as this group includes a huge number of individuals with different backgrounds, lifestyles, family situations, health, etc. [5,16]. Social gerontology differentiates between “the third age” and “the fourth age” [17], where the third refers to a situation where you are able to do things you would not be able to do while working (“energetic pensioner” in good health and with an active social life) and the fourth is a phase of life where you are increasingly dependent on others. Äldredelegationen [The old-age delegation] (2007-2008) notes in its findings that the needs vary depending on age, background and living situation.

The US model of retirement communities is increasingly being exported. In China more than a quarter of the population will be over 65 by 2050. The elderly population have traditionally been taken care of by the extended family-often with three generations living together. But demographic changes are severely challenging that family unit. The one child policy combined with longer life expectancy means that a typical married couple could be looking after four parents and up to eight grandparents [18]. Also elderly in living environments (indoors) is an important element. Mercer Consulting (Organizations that does yearly surveys of cities with highest quality of life) has designed an objective way of measuring quality of living for expatriates based on factors that people consider representative of quality of living. Once a year, Mercer conducts a quality of living study in over 380 cities worldwide based on detailed assessments and evaluations of 10 key categories and 39 criteria or factors, each having coherent weightings reflecting their relative importance [19].

Newsworthiness

As mentioned above, interest in the field of the elderly and urban environment/urban planning has grown in recent years. But while the research field has been explored internationally, it remains a fairly undeveloped area in Swedish research. Certain issues regarding what a good urban and living environment is for the elderly are universal and Sweden can obtain a significant amount of knowledge that can be applied to Swedish conditions. But when it comes to, for example, social structure and planning context, the conditions differ significantly between countries, and here there is a need to obtain knowledge of and analyze the Swedish context. What are the needs like in Sweden today and in the future? How can ageing-related issues be integrated into Swedish urban and social planning? What challenges and (currently) unutilized opportunities are there?

1. Focus on the physical environment outside of the home and overall, in the city district, city (and metropolitan region)

2. Focus on how the issues relating to the lives of the elderly and their opportunities for a good life (not just physical aspects) are included in municipalities’ spatial planning and other strategic work areas

We thus touch both on the content of the planning (physical environment) and the planning processes, as we feel that more knowledge is needed regarding both sides of the coin in order to offer better conditions for a good life into old age. So, we see an agefriendly city as a city that:

a) recognizes great diversity among older persons

b) promotes inclusion of the elderly in all areas of city and community life

c) respects their decisions and lifestyle choice whatever they may be, and

d) anticipates and responds flexibly to silver city - ageingrelated needs and preferences.

Housing, ageing in place, intergenerational senior living & cooperative living-the sustainable solutions?

Althaus, Birrer’s and Hugentobler’s work has highlighted that elderly people represent a diverse range of individuals, with different levels and types of need, knowledge and capacities [20]. What they point to is the following: “An important concept within the current social and health policy discussion on healthy ageing is ‘ageing in place’. This refers to elderly people living in their homes independently as long as possible, an option desired by most elderly people. It also makes sense in light of the economic costs associated with an ageing population and with very expensive care in nursing homes. Where full-time stationary care is not absolutely necessary, other living arrangement options with the necessary support structures are often more “humane”. To promote ‘ageing in place’, there are a variety of strategies and services operating at different levels, which include age-friendly environments, social services, assistive technologies, etc. The overall socio-political task of promoting the welfare of society, particularly for elderly people with special needs, requires the participation of a number of different organizations and actors, including private, public, non-profit and informal support networks. However, interactions between these different organizations and actors are often poorly coordinated. The research team in their project ‘Ageing in placechallenges and opportunities at the interface between property management and older residents’ seek to facilitate ageing in place (Figure 4). The research focuses on the role, challenges, and evolving service options of property management (profit-and non-profit) organizations in supporting elderly residents and cooperating with other relevant actors”. [“Ageing in place-Challenges and Potential at the interface of housing management and residents” [21].

Figure 4: Elderly ladies socializing in Fort Worth, Texas August 5th, 2011. (Mike Stone, Reuters).

The population of developed western Europe and Americasbasically all industrial countries is getting older. Still, housing, dwellings, houses are mostly built to suit young and mid-life citizens. Urbanists, planners and architects are now developing modern housing concepts for the ageing society. Older people on the whole no longer want to live in the same household with their heirs (resent study by the German Ministry of Transport, Construction and Urban Development has shown and confirmed this). According to the results of this survey, 94% of people over the age of 65 in Germany live independently in their own apartments or houses. At the same time, only 5% of all apartments are suitable for the elderly. For example, doors are often too narrow for a wheelchair to pass through. If we look elsewhere, there are similar problems in other industrialized countries, like Japan or South Korea, where the pressure to do something is even greater due to the fact that there are even more elderly people there than in Germany. Another problem that is akin to Italy, Spain, Portugal, Croatia and some other countries is the population decrease but also the dying of village and small-town hamlet elderly, that are either dying or leaving these places for good. There needs to be strategies in place, social and spatial to turn this trend around. There are many ideas for adapting apartments to the needs of the elderly, but not everyone can afford it. And in Germany, many people are at risk of poverty in old age.

Aging in place means basically that housing residents can live (and stay) in their homes while in their mid and late 80s and beyond though 3rd and 4th age, through expert planning & design of making homes and apartments more accessible. Another key concept is steering away from competition between the new urbanist movement and traditional senior housing, but rather finding ways to incorporate the two. HOPE VI program in the US has done just that in a number of places though it is fundamentally based on New Urbanism Principles of planning, design and management. Households of every age and condition of life. Many HOPE VI initiatives include housing for elderly households as well as families with children. A number of HOPE VI grants in the last two decades or three have converted older elderly housing into assisted living for frail seniors so that their aging residents can remain in their neighbourhood. HUD is also encouraging maximum accessibility in HOPE VI housing. A sense of community is one of key elements of such living and it is in the crux of any elderly project-cooperatives, ageing in place or intragenerational living. HOPE VI developments are designed for neighbourliness. They include attributes of traditional communities-front porches, wide front steps, sidewalks, neighbourhood pools, and playgroundsthat encourage residents to know one another and take an active interest in their neighbourhood. All of these tenants are American of course but in Europe, the traditional and common values of each country that are hallmarks of current and past lifestyles could easily be incorporated into any future designs or current redesigns [22-24].

Housing for the elderly is housing in old age-a problem around the world as we have seen. However, simply making a community of older adults in an urban environment will not produce true intergenerational interaction. Thoughtful design through additions of parks, festivals, and something as simple as park benches facing each other will help to break down barriers between different groups of people. Many countries with growing economies will soon experience what developed countries have already gone through: a mass flight from the countryside to the city. So one potent solution is of course intergenerational senior living which has been shaping the aging experience for quite a while, but real estate developers today (which was not the case before, nor it was with new urbanism or HOPE VI projects) are thinking of new ways to increase the benefits and successes of this concept that certainly has a future. In the US and UK as well as in Switzerland and Germany some developers view it as a master-community planning models, which require billion-dollar or euro investments and massive land acquisition for a mixed community where older adults can live in residential units that are submerged in an “new feel-good community of interest and care sort of urbanistic” vibe. This model is concerned not only with housing constructs, but with the community around the residential units. This new plan for intergenerational site planning, urban design and placemaking management comes from the core ideas of New Urbanism, where the belief is that the surrounding environment matters for quality of life, economy, and public health (though spatial determinism and communitarian trap should not be dismissed). An ideal goal of this model is for older adults to be offered active lifestyles, surrounded by a vibrant, bustling community that is a mix of different ages and ethnicities.

Developers are approaching this model through mixeduse communities, aging in place, and partnerships. Mixed-use communities are entire communities that are integrated with younger and older adults who can benefit and depend on one another, whether for assistance for young parents and their children, or older adults to have an exciting community around them.

Aim & goals of ageing city-silver city (ideas for viable research that can be translated into practice)

The aim of a deeper possible Silver City future Ageing Society development is to increase the Swedish knowledge on how the design of physical urban environments and the location of urban functions (housing, commerce, service, public transport etc.) affects the conditions for the elderly (65+) to live active, independent and rewarding social lives outside of their homes, and to increase the knowledge on how these issues are integrated/could be integrated better in Swedish social planning and urban development and also enabling/involving and informing the elderly. This attempt needs and has to have the four following goals:

1. To summarise and analyse existing (Swedish and international) research findings which concern the living environment of the elderly, urban design and urban planning.

2. To collect and analyse the need for research and development in Sweden concerning the living environment of the elderly, urban design and urban planning.

3. To study and analyse how issues concerning the living situation of the elderly are handled and integrated into municipal plans and strategies and into planning processes.

4. To propose and suggest how policy recommendations from the local, national and international research findings can be translated into viable planning and design solutions.

Existing research literature indicates that older people are more often immobile-not leaving the house on a given day, make fewer trips on days they go out, use non-car transport modes more frequently, and travel shorter distances-compared to younger population groups. Although there are age-specific mobility effects, literature reveals that older people’s travel behaviours are not uniform-there are large differences among older people regarding trip frequency, travel distance and mode choice, where place of residence and mode of transport used are explanatory factors [25]. From an urban planning and design point of view, especially having Sweden in mind, good access to community and social services influences older people’s independence and quality of life. By integrating senior’s housing into the local community avoids detachment from society. A varied range of housing options in the local area can accommodate changing needs as we get older (varying sizes, service/care levels, activities, prices, etc), and thus facilitate ageing in place.

We have found out that active ageing in place is important for older people’s quality of life, regarding physical and psychological health as well as social well-being. The design and quality of neighbourhood environments are important aspects of older people’s ability to actively age in place. In this section, we focus on key features regarding age-friendly planning and design of the built environment. The World Health Organization (WHO) has been a forerunner in gathering and dissolving knowledge about and formulating characteristics or features of age-friendly urban structures and environments. The WHO Global Age-friendly Cities Guide from 2007 [12] distribute these features into eight agefriendly topic areas:

a) Outdoor spaces and buildings

b) Transportation

c) Housing

d) Social participation

e) Respect and social inclusion

f) Civic participation and employment

g) Communication and information

h) Community support and health services

In the guide, each topic area is elaborated, discussed and formulated into sub-topics. When it comes to urban planning and design, the first three topic areas are the most important ones since these clearly can be directly affected by urban planning and design measures, and the other ones in a more indirect way. In the following part of this text, we will focus on these first three topic areas, putting an emphasis on age-friendly outdoor spaces. According to the WHO guide [12], the outdoor environment and public buildings are very important for the mobility, independence and quality of life of older people and has a great impact in their ability to “age in place”. Quality of life, accessibility and safety are key themes when it comes to age-friendly urban environments [12].

Target Groups and Conclusion

The world is ageing, particularly in advanced economies. Over the next 30 years, we will see an extra 15,000 people reaching retirement age in the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries every single day (Figure 5&6). By 2045 the proportion of the population aged over 65 will rise to 25%, from the current 16%. This equates to 146m more old people than there are today-totaling 1.4bn globally. At the same time, the younger population is steadily shrinking. In 2015, the young (those under 20 years old) counted for 24% of the population, a proportion which is expected to decrease to 21% by 2045. As the aim of this project was to increase knowledge on issues and urban planning processes in order to improve the living environment for the elderly, the project is mainly aimed at disseminating knowledge to municipal civil servants in urban planning and social welfare departments (urban planners, planning architects, traffic planners, housing strategists, administrators for the elderly etc.). Other secondary target groups which may benefit from the results include civil servants at government agencies and ministries, consultants (landscape architects, architects, planners) and employees at housing companies. It is our strong belief that the cities must adjust if older people are to maintain quality of life and that the ageing society continue to play an active role in the community avoiding loneliness and isolation. Isolation and loneliness have both a negative impact on health so tackling that is really important.

Figure 5: The Kalkbreite Co-op Complex & Zurich’s Cooperative Living.

Figure 6: Participative intragenerational renaissance planning (November 29th, 2016).

Creating Age friendly cities need urban planning and urban design to rethink the principles of town planning and housing development. Intragenerational living, ageing in place, cooperatives, etc. are modes of living operation where people can remain active longer in their lifetime homes and neighbourhoods, contributing to social capital, bridging and bonding, to street life and local economy. It is important when it comes to services, food stores, dentist, doctors, grocery, for transportation reasons mainly, older people tend to buy locally from people they know and trust, therefore enhancing local commerce. In terms of socializing and publicness, this will prove to be a more balanced solution for families because it promotes an easier intergenerational help and family bonding and family help. As for the future models maybe one can look towards the Swiss Zurich example that is built from prefabricated panels, the Intragenerational (Young and Ageing in Place) Kalkbreite co-op in that combines residential, working, and commercial typologies in one railway-straddling complex. The Zurich example, and many of its kind round EU and the World, suggest how co-ops will become a viable housing option for the 21st century. As many researchers assert, the existing city must be redesigned with the elderly population in mind and each generation can live in its own home, apartment, dwelling, according to its own rhythm and tastes, and still avoid the stress of longer, artificial or stranger routes to visit parents and grand-parents in old people’s homes, because when people age in place, the whole family is aging in place too and naturally getting used to it [6,23,26-29]. Last but not least: all of the above will prove to be a futile effort unless there is real-world drive towards strong interdisciplinary research where Gerontology & Geriatrics studies, Urban Social Geography, Universal Design, Urban Planning & Design, Transportation Studies, Social Care, Housing Studies and many others do not come together and work for a common systemic goal of creating better environments for our elderly. The current pandemic of COVID-19 where the Ageing Society has played the highest price is a testimony to that need [30].

References

- https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/ageing/

- http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Regional-statistik-och-kartor/Statistikatlasen/VisletBehallare/Aldrande-befolkning/

- (2013) The government of sweden/regeringen 2013: Ett värdigt liv-äldrepolitisk översikt 2006-2014. Regeringens skrivelse 14:57.

- Plouffe L, Kalache A (2010) Towards global age-friendly cities: determining urban features that promote active aging. J Urban Health 87(5): 733-739.

- Ann H, Judith P, Nigel W (2013) Planning for an ageing bo bra på äldre dar: Gabriella wiklund och stefan melin, svensk byggtjä Hjälpmedelsinstitutet Stockholm: Svensk Byggtjänst.

- Elizabeth B, Lynne M (2006) Inclusive urban design: Streets for life. Oxdon: Routledge. Abingdon, UK.

- Scott BM (2012) Liveable communities for aging populations: Urban design for longevity. Johan Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, USA.

- Henry C, Chamberlain DM, Hickie J (2012) Independent for life: Homes and neighbour hoods for an aging America. University of Texas Press, Austin, UK.

- Wai LC, Anne JE, Jeni W, Michael C, Helen B (2009) What makes a community age-friendly: A review of international literature. Australasian Journal on Ageing 28(3): 116-121.

- Dawn A, Phoebe L, Jon P, Tridib B, Hee C (2007) Creating elder-friendly communities. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 49(1-2): 1-18.

- Gilroy R (2008) Places that support human flourishing: Lessons from later life. Planning Theory & Practice 9(2): 145-163.

- Vanclay F (2002) Conceptualizing social impacts. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 22(3): 183-211.

- Buffel T, Phillipson C, Scharf TH (2012) Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities. Critical Social Policy. 32(4): 597-617.

- WHO (2007) Global age-friendly cities: a guide? Geneva: World Health Organization,

- Timonen V (2008) Ageing societies: A comparative introduction. In: Hill MG (Ed.), Journal of Social Policy. UK, 38(3): 224.

- OECD (1996) Ageing in OECD countries: A critical policy challenge. OECD Publishing, Paris, France.

- Sara A, Davidson K, Ginn J (2003) Gender and ageing: Changing roles and relationships (ageing & later life series). Open University Press, London, UK.

- Gilleard C, Higgs P (2013) Ageing, corporeality and embodiment. Anthem Press, London, UK.

- Grahame A (2016) Improving with age? How city design is adapting to older populations. Ageing Cities, The Guardian-Cities (2017-03-31) The Rockefeller Foundation, USA.

- Mercer (2007) Defining quality of living. Mercer Human Resource Consulting LLC, USA.

- Althaus E, Birrer A, Fuchs S, Heye C, Hugentobler M (2017) Ageing in place-challenges and potential at the interface of housing management and residents. Research Futures, Zurich, Switzerland.

- Haas T (2012) Housing 4 hope: Essays on sustainable dwellings and opportunity for all. Stockholm: Royal Institute of Technology US-AB Press, Sweden.

- Haas T, Locke R (2016) Sustainable urbanism solutions for breaking the bonds of concentrated poverty in public housing: just and dignified spaces & places for city living. Tongji Journal of Urban Design.

- Haas T, Cars G (2018) The senior city-anthology on the ageing society. (The Importance of Urban and Local Environment for Contentment into Old Age), Stockholm: US-AB Publishers with Rome: Sapienza and Stockholm: Riksbyggen, Sweden.

- Schwanen T (2010) The mobility of older people-an introduction. Journal of Transport Geography 18(5): 591-595.

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK (2001) Assisted living: needs, practices, and policies in residential care for the elderly. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, USA.

- Regnier VA, Scott AC (2001) Creating a therapeutic environment: lessons from northern European models. In: Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK (Eds.), Assisted Living: needs, practices, and policies in residential care for the elderly. The John Hopkins University Press, USA.

- Carvalho A, Heitor V, Cabrita R (2012) Ageing cities: redesigning the urban space. CITTA 5th Annual Conference on Planning Research-Planning and Ageing: Think, Act and Share Age-friendly Cities, University of Oporto, Portugal.

- Chris G, Paul H (2002) The third age: class, cohort or generation? Ageing and Society 22(3): 369-382.

- OECD (2015) Ageing in Cities. OECD Publishing, Paris.

© 2020 Tigran Haas. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)