- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics studies

Functionality and Attitudes in Relation to Aging of Elderly Women Practicing Physical Exercises

Daniel Vicentini de Oliveira1*, Nayla Dionízio Fogaşa2, Letícia Decimo Flesch1, Mateus Dias Antunes3, José Roberto Andrade do Nascimento Júnior3 and Daniel de Aguiar Pereira1

1Department of Gerontology, State University of Campinas, Brazil

2Department of Physical Education, Metropolitan College of Maringa, Brazil

3Departamento de Post-graduation in Health Promotion, University center of Maringa, Brazil

4Department of Physical Education, Federal University of the Sao Francisco Valley, Brazil

*Corresponding author: Daniel Vicentini de Oliveira, Department of Gerontology State University of Campinas, Tessália Vieira de Camargo Street 126. Zeferino Vaz University city, CEP: 13083-887 Campinas, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Submission: January 17, 2018; Published: February 21, 2018

ISSN : 2578-0093Volume2 Issue2

Abstract

The objective was to verify the attitudes regarding old age and the functional capacity of elderly women practicing physical exercises. This is a cross-sectional study, realized with 200 women. The Functional Protocol of the Latin American Development Group for Maturity (GDLAM) and the Scale for Assessment of Attitudes in Relation to Old Age was used. There was a significant correlation only in the stand up from sitting position test, with the domains of expectations regarding activity (r=-0.31), satisfaction with life (r=0.38) and death anxiety (r=-0.27). It can be concluded that there is correlation between some domains of the functional capacity test and the attitudes towards old age.

Keywords: Physical fitness; Motor activity; Aging; Health promotion

Abbreviations: ADLS: Activities of Daily Living; LADGM: Latin American Development Group for Maturity; W10M: Walk 10 meters; SULP: Stand Up from Laying Position; SUCWH: Sit and Stand Up from a Chair and Walk around the House; SUSP: Stand Up from Sitting Position; DUT: Dress and Undress a T-shirt

Introduction

Although gerontological evaluation aims to intervene on physical, cognitive, affective and social performance, the focus of care has been on the functional capacity due to its importance for the well-being of the elderly [1]. Functional capacity can be defined as the management of activities of daily living in an independent manner [2].

Functionality in old age is related to biological, psychological and social factors. Thus, decrease in functionality has been associated with variables related to physical health such as greater number of physical symptoms [3] and chronic non-communicable diseases [4]. There have been also associations with psychological factors, such as depressive symptoms [3,4] less satisfaction with life [5] and lower cognitive functioning [6]. In addition, it has also been verified association between lower functionality and worse self-rated health [3,4], higher consumption of medication [4] and greater use of health services [7]. With regard to sociodemographic factors, there have been associations between lower functionality and older adults [3-5,8] with less years of schooling [3] and lower income [5].

Longitudinal population studies have accompanied the decrease in functional capacity and allowed the identification of some predictors. A study of Kim [9], who used a representative sample of 2,824 older Koreans, showed that poor or very poor self-rated health status was a predictor of decline in the functional capacity of independent elderly people after two years of follow-up. Arnau [10] studied elderly Spanish patients aged 75 and over with a year of follow-up and identified that previous hospitalizations, cognitive impairment and functional impairment of the lower limbs were independent risk factors for functional capacity decline.

In addition, risk factors for functional capacity reduction appear to vary with age. A prospective population-based cohort study with 264 Japanese women [11] showed that the decrease in hand grip strength and presence of pain were significantly associated with a greater risk of decline in activities of daily living (ADLs) for women aged between 40 and 64 years. However, in women aged 65 years and over, decreased walking speed, presence of comorbidities and pain were associated with a decline in ADLs.

Functional capacity has bio-psychosocial implications and is a fundamental aspect to be considered when studying and proposing interventions that aim to promote healthy aging and well-being in old age. Therefore, it is crucial to study the relationship between functional capacity and the attitudes that elderly people have towards aging. Attitudes have a social basis, are related to direct and indirect experiences and to the historical and cultural context [5]. Elderly people's attitudes about aging can have an effect on their behavior; their beliefs about their ability are associated with their physical and cognitive performance [12]. In addition, negative attitudes towards old age may indicate a risk for the functionality of the elderly person [11].

However, due to the multidimensionality of health in old age and different forms and conditions of aging, it is necessary to identify whether this relationship is present in any condition. For example, in the active elderly and if it is true for any aspect of functional capacity.

Considering this possible relation between attitudes and functionality, the present study aimed to verify the correlation between functionality ad attitudes regarding old age of elderly women practicing physical exercises at Sports Centers in the city of Maringa, PR.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional and observational study based on primary data, approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Center of Maringa, through opinion number 1,742,192/2016.

Study participants were elderly women aged 60 years or over who practiced physical exercises in one of the nine Sports Centers of the municipality, with a frequency of at least twice a week, for at least three months. Older males were excluded due to their low prevalence in the exercises offered by the centers; elderly people who used accessories to help walking (walking sticks, walking frames, wheelchairs) and elderly people with cognitive and physical, perceptive changes that prevented the application of data collection instruments were also excluded. The final sample consisted of 200 elderly women, chosen by convenience.

To characterize the profile of the elderly women, a sociodemographic questionnaire was elaborated by the researchers themselves, containing questions regarding age, race, education, smoking, retirement, self-perception of health, occupational situation, monthly income, marital status, presence of illnesses, history of falls, and also questions related to the sports center, such as which activities they performed in the center, how long they had been exercising and what the weekly frequency was.

The functional capacity was evaluated through the Protocol of the Latin American Development Group for Maturity (LADGM), composed of five tests: walk 10 meters (W10M), stand up from laying position (SULP), sit and stand up from a chair and walk around the house (SUCWH), stand up from sitting position (SUSP) and dress and undress a t-shirt (DUT), all calculated by time in seconds. The shorter time on each test demonstrates better functionality, and vice versa. Each test also receives a rating that ranges from weak, fair, good, and very good [13].

The total score was calculated as follows:

LADGM = [W10M + SUSP+ SULP + DUTx2] + SUCWH/4

It was also used the Scale for Assessment of Attitudes in Relation to Old Age, originally elaborated by Sheppard [13] and validated for the Portuguese language by Neri [14]. The instrument is composed of 20 items that evaluate feelings of satisfaction in relation to old age (self-esteem, sexuality, self-fulfillment, leisure and companionship in questions 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19 and 20) and feelings of loss in relation to old age (uncertainty, death, dependence, loneliness and fear about the future in questions 2, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17). The items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from "totally disagree" (1) to "strongly agree" (5). The higher the mean of each dimension, the greater is the degree of feelings of satisfaction regarding old age or the feelings of loss in relation to old age.

The data collection was performed in eight (all) sports centers of the municipality of Maringa, Parana state, after the authorization of the Secretariat of Sports and Leisure. The elderly were informed about the purpose and justification of the research, and those who agreed to participate signed the Informed Consent Form (ICF). The data were collected before the practice of exercises by the elderly women in order to avoid possible interferences in the results, and after the previous scheduling with physical education teachers of each class. The data collection period was between June and August 2016.

Data analysis was performed by using SPSS 22.0 Software, through a descriptive and inferential statistics approach. Frequency and percentage were used as descriptive measures for the categorical variables. For the numerical variables, the normality of the data was initially checked by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To verify the impact of self-esteem on the domains of quality of life of women practicing exercise, a regression model was conducted with variables that obtained a significant correlation (p <0.05). The existence of outliers was evaluated by the square distance of Mahalanobis (D2) and the univariate normality of the variables was evaluated by the uni and multivariate asymmetry (ISkI<3) and kurtosis coefficients (IKuI<10). As the data did not present a normal distribution, the Bollen-Stine's Bootstrap technique was used to correct the value of the coefficients estimated by the Maximum Likelihood method implemented in AMOS software version 18.0. There were no DM2 values indicating the existence of outliers, nor sufficiently strong correlations between the variables indicating the absence of problems with multicollinearity (Variance Inflation Factors <5.0). Based on Kline's recommendations [15] the interpretation of regression coefficients had as reference: little effect for coefficients <0.20, medium effect for coefficients up to 0.49 and strong effect for coefficients> 0.50 (p <0.05).

Results

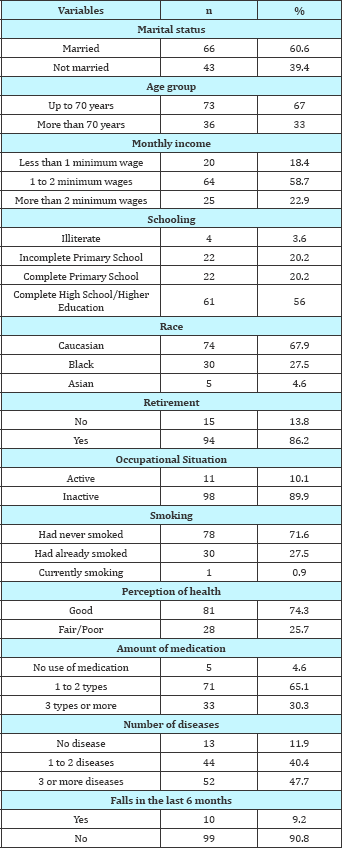

There was prevalence of married women (60.6%), aged up to 70 years (67.0%), with a monthly income of 1 to 2 minimum wages (58.7%), with a complete high school/higher education (50.0%), of the Caucasian race (67.9%), retired (86.2%), who did not exercise paid work anymore (89.9%) and who had never smoked (71.6%).

Regarding the health profile of elderly women practicing physical activity in the sports centers of Maringa-PR it was verified that the majority had a good health perception (74.3%), had no history of falls in the last 6 months (90.8%), has 3 or more diseases (47.7%) and used 1 to 2 types of drugs regularly (65.1%).

Table 1

Table 1: Frequency distribution of the socio-demographic profile of elderly women practicing physical exercises in the sports centers of the city of Maringa-PR, Brazil, 2016.

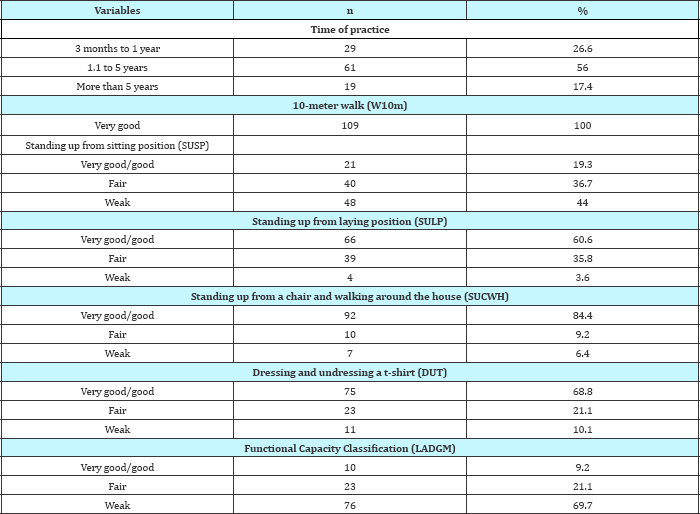

When analyzing the physical activity profile and the functional capacity of the elderly women practicing physical exercises in the sports centers of the city of Maringa-PR (Table 1), it was verified that the majority had practice time between 1 and 5 years (56.0%) and had very good/good level in the following functional capacity tests: 10-meter walk (100.0%); stand up from laying position (60.6%); sit and stand up from a chair and walk around the house (84.4%); and dress and undress a t-shirt (68.8%). In the stand up from sitting position and in the functional capacity classification by LADGM (Table 2), the majority of the elderly women presented a weak level (44.4% and 69.7%, respectively).

Table 2

Table 2: Frequency distribution of the physical activity profile and the functional capacity of elderly women practicing physical exercises in the sports centers of the city of Maringa-PR, Brazil, 2016.

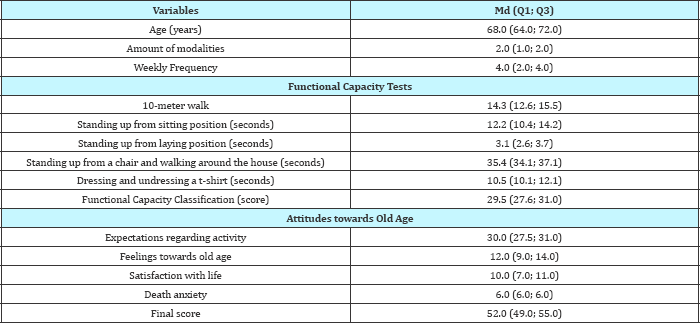

When analyzing the age, the number of modalities practiced and the weekly frequency (Table 3), it was observed that the elderly women had a median age of 68.0 years, two types of activities practiced and frequency of four times a week. Regarding functional capacity (Table 3), the elderly women presented satisfactory results in 10-meter walk tests (Md=14.3), SULP (Md=3.1), SUCWH (Md=35.4) and DUT (Md=10.5). However, the results in the SUSP (Md=12.2) and LADGM (Md = 29.5) tests may be considered unsatisfactory.

Table 3:

Table 3: Descriptive analysis of age, amount of modalities practiced, weekly frequency and functional capacity tests of elderly women practicing physical exercises in the sports centers of the city of Maringa, Brazil, 2016.

Table 3 presents the correlation between functional capacity and attitudes regarding old age of elderly women practicing physical exercises in the sports centers of the city of Maringa-PR.

Table 4:

Table 4: Correlation between attitudes towards old age and functional capacity of elderly women practicing physical exercises in the sports centers of the city of Maringa, Brazil, 2016.

A significant correlation was found only in the SUSP test with the domains of expectations regarding activity (r=-0.31), satisfaction with life (r=0.38) and death anxiety (r=-0.27), which indicates a weak relationship between increased functional capacity in relation to standing up from the sitting position and increased satisfaction with life and reduced expectations regarding activity and death anxiety. There was no significant correlation regarding functional capacity and attitudes regarding old age with age, weekly frequency and number of modalities practiced.

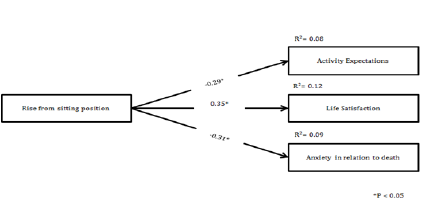

In order to verify the impact of the functional capacity on the attitudes regarding the old age of the elderly women practicing physical exercises in the sports centers of the city of Maringa- PR, after the analysis of the correlation, a regression model was conducted (Figure 1) between functional capacity tests and attitudinal factors in relation to old age that presented a significant correlation (p<0.05).

Figure 1

Figure 1: Model of regression of the impact of functional capacity on the attitudes in relation to old age of elderly women practicing physical exercises in the sports centers of the city of Maringâ-PR, Brazil, 2016.

It was verified that (Figure 1) SUSP (functional capacity) had a significant impact (p<0.05) on the variability of expectations regarding activities (8%), satisfaction with life (12%), death anxiety (9%). In relation to the individual trajectories of the regression model, it was verified that the improvement in the result of SUSP test has a significant (p<0.05) and moderate (β>0.50) effect on the expectations regarding activities (β=-0.29), satisfaction with life (β=0.35) and death anxiety (β=-0.31).

Discussion

The performance of the elderly women in LADGM was not homogeneous in all the tests. Although they presented satisfactory results in four of the five tests (10-meter walk, SULP, SUSWH and DUT), they presented unsatisfactory results in the SUSP test and in the total evaluation of the protocol. Brazilian studies using the LADGM Protocol show variability in relation to their results. Such variation has been justified by the characteristics of the sample, such as the age of the participants, degree and type of activities developed, among other health conditions [16].

Nevertheless, it is possible to find some similarities of the results of this study with other studies with elderly people in Brazil. For example, in the study of Dantas [17] conducted with 2,158 elderly women aged from 60 to 88 years and independent in daily life activities, the means of the tests for each age group were predominantly classified as regular. In the study of Oliveira [18] with 120 elderly women practicing four different types of physical activities, the results were weak for all the tests.

With respect to functional capacity and attitudes towards old age, it is possible to verify relationship between variables. The correlation was significant for only one test (SUSP); however, when observing the variation between the results of each test, this one showed the greatest variability.

Regression analysis showed that SUSP was associated with three of the four subscales of the attitudes inventory. Other studies have shown an association between attitudes regarding old age and physical health. In the study of Witham [19], with elderly with heart failure, the attitude was associated with exercise capacity (performance) measured by the 6-minute walk test. Thorpe [20] evaluated 300 middle-aged adults aged from 49 to 51 years in New Zealand and the data showed an association between chronic non- communicable diseases and attitudes towards one's own aging. It was also identified an association between attitudes regarding old age and self-reported physical health [21,22] and consumption of medicines [23].

It is interesting to note that the subscales of the attitude inventory behaved differently in relation to SUSP. The scale of satisfaction with life was positively associated with SUSP, that is, the greater the functional capacity in this test, the greater the satisfaction with aging. Such association can be understood since previous studies have identified an association between measures of functional capacity and satisfaction. A study with 114 women aged 60 years and over identified an association between quality of life and functional evaluation tests (including SUSP) [24]. Another study with patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease identified an association between the SUSP test and the quality of life related to the disease [25].

However, expectations regarding activity and death anxiety were negatively associated with SUSP. Thus, the better the performance on the test, the worse the attitudes toward old age in these factors. These data demonstrate that the relationship between functional capacity and attitudes towards old age may be more complex. Silva [26] evaluated the attitudes regarding the old age of 54 elderly people and also found differences in their answers regarding different domains of attitudes. Elderly people showed that they perceive gains in old age (integrity, satisfaction and the possibility of being happy). At the same time, they evidenced fear of dependence, loneliness, inactivity and death. Luchesi [23] also identified divergences between attitudinal domains in a sample with elderly caregivers. They reported more positive attitudes regarding social relationships and more negative attitudes toward agency.

This study showed that this association needs to be contextualized. Information on the attitudes related to old age and functional ability may help to understand the performance of activities by the elderly, and can bring information for the construction of interventions, but it is necessary to understand the specificities between characteristics of the elderly (for example: age, gender, educational level, chronic illness, level of physical activity performed) and the attitudinal aspects with respect to the aging. This study suggests that the relationship between attitudes related to age and functional capacity is complex and needs to be further investigated.

One limitation of this research is that it is a cross-sectional study. The assessment of functional capacity occurred in only one moment. Thus, it was not possible to recognize the recent process of decline and/or functional stability of the elderly participants. Probably, the perception of the decline and its speed influenced the attitudes of the surveyed women. Another limitation is that all the evaluated elderly women participated in physical exercises; therefore, they were already different from the elderly in society Longitudinal studies may help identifying whether and how changes in functional capacity may relate to changes in the attitude of the elderly with regard to old age. It is important to consider that other variables may have influenced this association. Further studies should be developed to deepen the relation between functional capacity and attitudes towards old age.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that there is correlation between some domains of the functional capacity test and the attitudes towards old age; however, this correlation was weak, which does not allow establishing an association between attitudes and functionality. Thus, in this study, the attitudes of the elderly towards aging do not seem to serve as predictors for their physical performance.

References

- Papaléo Netto M (2016) Estudo da velhice: Histórico, definigao de campo e termos básicos. In: Freitas EF, Py L, Gorzoni ML, Doll J, Candado FAX (Eds.), organizadores Tratado de Geriatria e Gerontologia. Rio de Janeiro, p. 3-13.

- Pereira LC, Figueiredo F, Livramento M, Beleza CMF, Andrade EMLR, et al. (2017) Fatores preditores para incapacidade funcional de idosos atendidos na atengao básica. Rev Bras Enferm 70(1): 106-112.

- López S, Montero P, Carmenate M, Avendano M (2014) Functional decline over 2 years in older Spanish adults: Evidence from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe: Functional decline in older Spanish adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int 14(2): 403-412.

- Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H (2016) Association Between Social Participation and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Epidemiol 26(10): 553-561.

- Pinto JM, Neri AL (2013) Doengas crónicas, capacidade funcional, envolvimento social e satisfagao em idosos comunitários: Estudo Fibra. Ciènc Saúde Coletiva 18(12): 3449-3460.

- Figueiredo CS, Assis MG, Silva SLA, Dias RC, Mancini MC (2013) Functional and cognitive changes in community-dwelling elderly: Longitudinal study. Braz J Phys Ther 17(3): 297-306.

- Fialho CB, Costa MFL, Giacomin KC, Loyola Filho AI (2014) Capacidade funcional e uso de servigos de saúde por idosos da Regiao Metropolitana de Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brasil: um estudo de base populacional. Cad Saúde Pública 30(3): 599-610.

- Ailshire J, Crimmins E (2013) Physical and Biological Indicators of Health and Functioning in US Oldest Old. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr 33(1): 193-215.

- Kim SH, Cho B, Won CW, Hong YH, Son KY (2016) Self-reported health status as a predictor of functional decline in a community-dwelling elderly population: Nationwide longitudinal survey in Korea. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17(6): 885-892.

- Arnau A, Espaulella J, Serrarols M, Canudas J, Formiga F, et al. (2016) Risk factors for functional decline in a population aged 75 years and older without total dependence: A one-year follow-up. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 65(1): 239-247.

- Okabe T, Abe Y, Tomita Y, Mizukami S, Kanagae M, et al. (2016) Age- specific risk factors for incident disability in activities of daily living among middle-aged and elderly community-dwelling Japanese women during an 8-9-year follow up: The Hizen-Oshima study: Age-specific risk factors of disability. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17(7): 1096-1101.

- Hess TM (2005) Attitudes toward Aging and Their Effects in Behavior. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, organizadores (Eds.), Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. Sao Paulo, p. 564-565.

- Sheppard A (1981) Attitudes towards aging: analysis of an attitudes inventory for younger adults: abstracted. Catal Selec Doc Psychol 11(3):

- Neri AL (1986) O Inventàrio Sheppard pra medida de atitude em relagao à velhice e sua adaptagao para o portugués. Estud Psicol Camp 2(2):

- Kline RB (2012) Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelin. The Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Dantas EHM, Gomes de Souza Vale R (2004) Protocolo GDLAM de avaliagao da autonomia funcional. Fit Perform J 3(3):

- Dantas EH, Figueira HA, Emygdio RF, Vale RGS (2014) Functional Autonomy Gdl Am Protocol Classification Pattern in Elderly Women. Indian J Appl Res 4(7).

- Oliveira DV, Araujo APS, Bertolini SMMG (2015) Cognitive and functional ability of elderly women practitioners of different modalities of exercise. Rev Rede Enferm Nordeste 16(6): 872-880.

- Witham MD, Argo IS, Johnston DW, Struthers AD, McMurdo MET (2006) Predictors of exercise capacity and everyday activity in older heart failure patients. Eur J Heart Fail 8(2): 203-207.

- Thorpe AM, Pearson JF, Schluter PJ, Spittlehouse JK, Joyce PR (2014) Attitudes to aging in midlife are related to health conditions and mood. Int Psychogeriatr 26(12): 2061-2071.

- Kavirajan H, Vahia IV, Thompson WK, Depp C, Allison M, et al. (2011) Attitude toward own aging and mental health in post-menopausal women. Asian J Psychiatry 4(1): 2061-2071.

- Bryant C, Bei B, Gilson K, Komiti A, Jackson H, et al. (2012) The relationship between attitudes to aging and physical and mental healthn in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 24(10): 1674-1683.

- Luchesi B (2015) Idosos cudadors de idosos: Atitudes em relaçao à velhice, sobrecarga, estresse e sintomas depressivos [tese]. Universidade de Sao Paulo, Ribeirao Preto, Brazil.

- Aragao JCB, Dantas EH, Dantas BHA (2002) Efeitos da resistência muscular localizada visando a autonomia funcional e a qualidade de vida do idoso. Fit Perform J (3):

- Stedile NRA (2013) Reabilitaçao pulmonar em pacientes com doença pulmonar obstrutiva crónica : associaçao entre capacidade funcional, atividades de vida diària e qualidade de vida [dissertaçao]. Unversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

- Silva LCC, Farias LMB, Oliveira TS, Rabelo DF (2012) Atitude de idosos em relaçao à velhice e bem-estar psicológico. Rev Kairós Gerontologia 15(2): 119-140.

© 2018 Daniel Vicentini de Oliveira, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)