- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

Longterm Mortality among Chronic Complex Patients with polypharmacy: Results of Community- Based Prospective Study

Muria Subirats E1, Ballesta Ors J1, Clua Espuny JL1*, González Henares MA1, Queralt Tomas MLL1, Panisello Tafalla A1, Lucas Noll J1 and Gil Guillen VF2

1Health Department, Catalonian Health Institute, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain

2Emotional Department, Cátedra Medicina de Familia, Spain

*Corresponding author: Clua Espuny, J Luis EAP Tortosa Est, Institut Català Salut, SAP Terres de l'Ebre, Health Department, Generalitat de Catalunya, Plaça Carrilet, s/núm Tortosa 43500, Spain

Submission: January 10, 2018; Published: February 09, 2018

ISSN : 2578-0093Volume2 Issue1

Abstract

Introduction: The polypharmacy is common in ambulatory care, hospital and nursing home patients. Over the last 20-30 years, problems related to aging, multi morbidity, and polypharmacy have become a prominent issue in global healthcare. In the developed countries around 3-4% of the people could be identified as chronic complex patient and they are increasingly at risk of polypharmacy. The main objective of this study we as to evaluate the association of polypharmacy and mortality risk.

Materials and Methods: We carried out a multicenter and prospective cohort study of mortality incidence from 01.01.2013 to 30.09.2016 among 825 adult patients registered in the electronic health record of Primary Care as Chronic Complex Outpatient. To predict hazard ratios, mean survival time, and survival probabilities used a multivariate Cox regression.

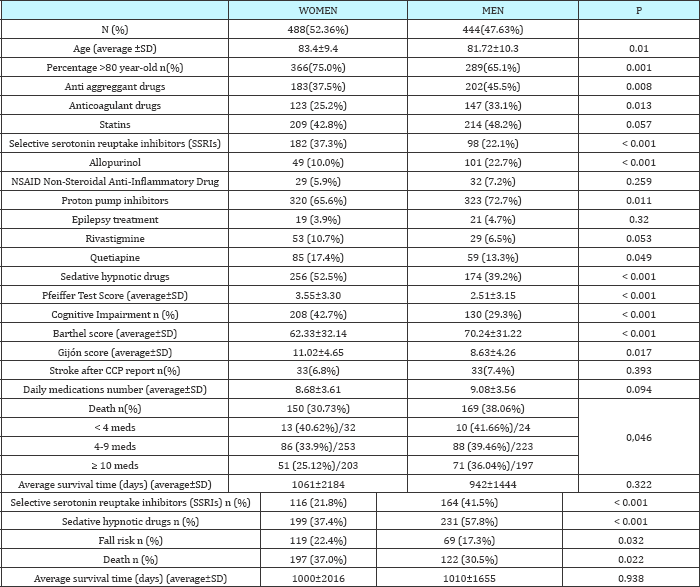

Results: 932 CCP cases were included (52.3% women). Average age was 82.5 yr (CI95% 81.8-83.2). 91.6% CCP had ≥4 and the 42.9% CCP had ≥10 active medication. The mean number of medications used by participants was 9.0±3.6 daily medications. Proton pump inhibitors (68.5%), statins (45.5%), hypnotics (45.3%), anti aggreggants (41.5%) and SSRIs (30.1%) were the most commonly used medications. The patients with fall risk or Barthel score <60 associated to polypharmacy >10 active medications had higher mortality. We observed a strong association that persisted even after adjustment for known mortality risk factors: age [HR 1.04 CI95 1.02-1.05, p < 0.001], Charlson score [HR 1.21 CI95 1.12-1.30, p<0.001] and Barthel [HR0. 988 CI95 0,985-0.992, p<0.001].

Conclusion: This study confirms the polypharmacy (> 10) was associated with increased risk of mortality if there was associated risk of falling or functional disability (Barthel score<60) and they are a useful indicator to identify subjects eligible for preventive measures in public health strategies.

Keywords: Falls; Chronic complex patient; Mortality; Polypharmacy; Fall risk; Disability.

Abbreviations: CCP: Chronic and Complex Patient; HR: Hazard Risk; IDIAP: Primary Care Research Institute Jordi Gol I Gurina; PIIC: Shared Individual Intervention Plan [Pla d'intervencio individualitzat compartit (PIIC)]; SD: Standart Deviation; SSRI: Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor; TTR: Time in Therapeutic Range

Introduction

We face an epidemic of multi-morbidity and rising complexity of health needs [1,2] resulting from changing demographics and global circumstances. In the developed countries around 3-4% of the people could be identified as chronic complex patient and they are increasingly at risk of polypharmacy due to the need to treat the various disease states that develop as a patient ages. The polypharmacy is common in ambulatory care, hospital and nursing home patients [3]. Over the last 20-30 years, problems related to aging, multimorbidity, and polypharmacy have become a prominent issue in global healthcare.

Unfortunately, there are many negative consequences associated with polypharmacy. Specifically, the burden of taking multiple medications has been associated with greater health care costs and an increased risk of adverse drug events, drug- interactions, medication non-adherence, reduced functional capacity and multiple geriatric syndromes. The prevention of these negative effects is of major importance because they engender significant morbidity and mortality. Nowadays the polypharmacy among older people are major issues for health and social care providers [4-7].

The goals of this research were

(i) To provide a description of the epidemiology of polypharmacy and mortality risk among people registered as chronic complex outpatients and

(ii) To explore risk factors differences in the association of outcome factors on mortality. We hypothesized that, given the high burden of multi morbidity in Chronic Complex Patients (CCP), polypharmacy would be associated with a higher risk of death. This review discusses how primary care might tackle these new challenges of the aging population.

Materials and Methods

We carried out a multicenter and prospective cohort study of mortality incidence from 01.01.2013 to 30.09.2016 among out-ofhospital patients over 65 years old attending primary care teams in the Terres de l'Ebre health area in Catalonia (Spain). All people included were managed by the Public Health System in Catalonia. The overall number of CCP registered was 3,490 people. We included a randomized sample of 825 adult patients registered in the electronic health record of Primary Care as Chronic Complex Outpatient (CCP) in the periode 01/01/2013-31/12/2014. Patients were excluded if they resided in a long-term institutional setting. Alpha Risk=0.05; Precision=0.03.

Patient outcome was followed until death or study end (30.09.2016) since date of report as CCP in the electronic health record. Data included demographics, functional, comorbidity, cognitive and social assessment, and were collected directly from the Shared Individual Intervention Plan [Pla d’intervencio individualitzat compartit (PIIC)] written and managed by Nursing service in Primary care. In the PIIC, determinants related to the personal factors, social and physical environment are described as well a tailored personal approach according the patient's preferences in case of hospital readmission o emergency use, and main caregiver. The report is updated automatically to ensure that relevant information is shared across the electronic health record. Currently 82% of people registered as CCP have this basic information in their PIIC.

Definitions

Chronic Complex Patient (CCP) definition: Those who meet at least four of the next criteria: Age (≥65 year-old). Chronic comorbidities (≥4) Psychosocial disorders (cognitive impairment or psychological disorder with functional disability). Geriatric conditions such as functional disability (Barthel score <55, living to assisted living, nursing home, or in-home caregivers) or recurrent falls or fall risk. Previous high health care utilization (two hospitalizations no programmed for exacerbation of chronic pathologies or three emergency department visits in last year). Number of active medications last six months (≥;4 active medications). Living alone or with caregiver ≥75 year-old. "They defined the "Chronic Complex Patient” [7] as those who have chronic illness and also complex clinical situations which make their management significantly far more difficult.

There are problems in defining falls risk as many studies fail to specify an operational definition, leaving room for interpretation. A fall is an unintentional event that results in the person coming to rest on the ground or another lower level (W19.9 code in the electronic health record). A fall was defined as the result of any event that caused the patient to end up on the ground against their will, according to the WHO definition [8]. We used "the report clinical in the the electronic health record that a person had falls risk or previous recurrent falls with or without any serious injury” If a patient is thought to be high by medical or nursing staff, allied health, or carers such patients will be identified as "fall risk” in the PIIC. This might include mention of the patient s level of orientation and cognition, gait and balance, continence status, and number and types of prescribed medications, as well as number of diagnosis.

Variables

A. Sex: woman (0) man (1)

B. Age: <80 year-old (1), ≥80 year-old (2).

C. Number CCP criteria: <4 (0) ≥4 (1). Charlson comorbidity index [9]. Short version.

D. Polypharmacy (defined as four or more daily medications): <5 (0), entre 5-9 (1), and ≥10 (2).

Oral anticoagulants (acenocumarol or warfarina) con TTR ≥60% (1), si TRT <60% (2) or New Oral Anticoagulants NOACs (0). Antidepressants and/or, sedating or other drugs affecting the neurologic.

E. system: man (1), woman (2).

F. Recurrent falls or fall risk: no (0), yes (1).

G. Hypertension not controlled by therapy (≥ 160/90 mmHg): no (0), yes (1).

H. Alcoholism abuse vs dependence: no (0), yes (1)

I. Presence de cognitive impairment [10]: a disease-specific diagnosis of cognitive impairment, without specification of subtype or severity, was used and mesured by Pfeiffer test [2]: [0-2 errors]=Intact Intellectual Functioning (1); [≥3 errors]=Mild to severe Intellectual Impairment (2)].

J. Presence de disability: score in [Barthel ≥60 (1) <60 (2)] or in [Rankin <4 (1) 5 (2)]

K. Socio familiar risk: score in Gijon [11] scale 10-14 (1) ≥15(2)]

We conducted descriptive analysis to examine participants' baseline characteristic. Demographic data were summarized using mean and SD or median and quartiles for continuous variables and percentages for categorical data. Data analysis information extracted was the adjusted risk estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical tests of homogeneity were performed using Cochran's Chi-squared test for homogeneity (Q) and the percentage of total variation across studies attributable to heterogeneity (I2). Using univariate linear regression analysis with medication count as a continuous outcome variable, we identified explanatory variables that had significant (p≤0.05) univariate linear associations with medication count.

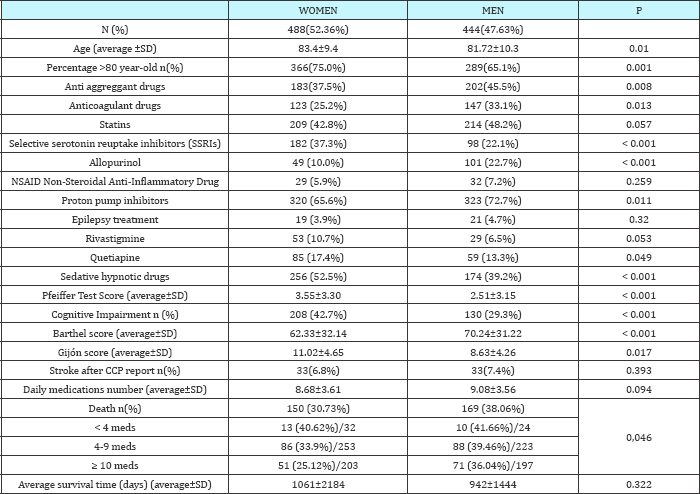

Using stepwise multiple linear regression analysis with medication count as the outcome variable and significant explanatory variables from univariate linear regression analysis, we identified factors that remained significantly and independently associated with medication count. To predict hazard ratios, mean survival time, and survival probabilities used a multivariate Cox regression. The variables were included in a multivariable model Cox to identify their influence on the mortality. In the survival analyses of risk factors for death, follow-up began at the start of the study, and patients were censored when follow-up ended for reasons other than death. A graphical presentation of the survival of fallers versus non fall risk was made using an adaptation of the Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator (Table 1).

Table 1: Basal Characteristics CCP by sex.

Ethics approval was granted by Ethics Commitee Research Institut Primary Care Jordi Gol i Gurina (IDIAP), Health Department, Generalitat de Cataluña.

Results and Discussion

932 CCP cases were included (52.3% women). The basal characteristics are showed in table 1. Average age was 82.5 yr (CI95% 81.8-83.2). Average number of CCP criteria was 3.83 (CI 95% 3.753.92). The mean number of medications used by participants was 9.0±3.6 daily medications. Proton pump inhibitors (68.5%), statins (45.5%), hypnotics (45.3%), anti aggreggants (41.5%) and SSRIs (30.1%) were the most commonly used medications. The women were older age, lower in Barthel score, more cognitive impairment and more prescription of SSRIs and sedative drugs. The global mortality was 32, 5% (n=257), higher among men. The average survival time was 1,032.13 days (DS 2022.0; IC95% [890.861173.40]). In the survival analyses of risk for death it seems that should be added more factors, the outcome independent factors were: age [HR 1.04 CI95% 1.02-1.05, p <0.001], the genre [HR 0.61 CI95% 0.48-0.78, p<0.001], the Charlson score [HR 1.19 CI95% 1. 09-1.29, p <0.001], the Barthel score [HR 0.98 CI95% 0.98-0.99, p <0.001].

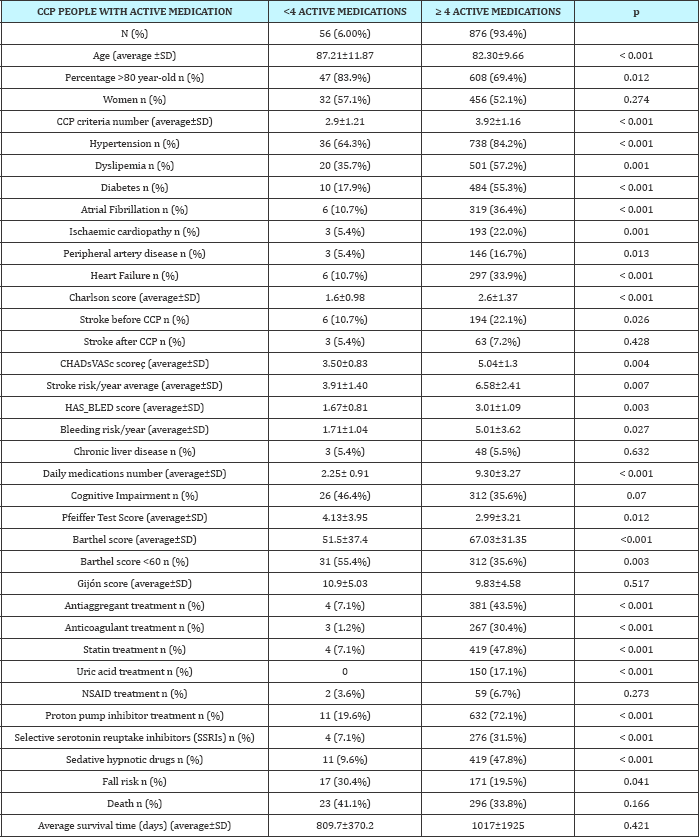

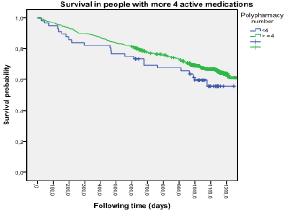

876 (93.4%) cases had ≥4 active medications (Table 2) and were less aged, with multiple cardiovascular chronic conditions and less cognitive impairment. At baseline participants who took ≥4 concurrent medications compared with those who took <4 concurrent medications were more likely to: be women, be less aged (82.3±SD 9.6, p<0.001), have more CCP criteria (3.9±SD1.1, p<0.001) and higher Charlson score (2.6±SD 1.3, p<0.001), lower score in Pfeiffer test (2.9±SD3.2, p<0.012), higher score in Barthel risk (19.5 vs 30.4%, p 0.041), and the long term survival was not index (67.0±SD31.3, p<0.001)with lower baseline burden of different (Figure 1). functional dependence in one or more daily activities, lower fall risk (19.5 vs 30.4%, p 0.041), and the long term survival was not different (Figure 1). .

Table 2: Baseline characteristics participants ≥ 4 concurrent medications vs < 4

Figure 1: Survival CCP and polypharmacy (≥ 4 vs >4).

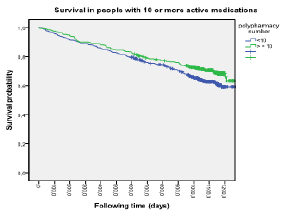

Figure 2: Survival CCP and polypharmacy (≥ 10 vs >10).

Table 3: Baseline characteristics participants ≥10 concurrent medications vs <10.

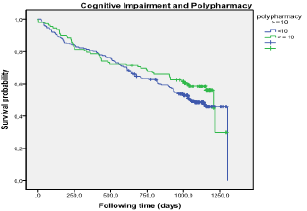

400 (42.9%) cases had ≥10 active medications (Table 3). At baseline participants who took ≥10 concurrent medications compared with those who took<10 concurrent medications were more likely to: be less Older, with multiple cardiovascular chronic conditions and less cognitive impairment. At baseline participants who took ≥10 concurrent medications compared with those who took <10 concurrent medications were more likely to: be less aged (81.2±SD 9.1, p <0.001); and have more higher Charlson score (2.8±SD 1.4, p <0.001), lower score in Pfeiffer test (2.4±SD2.8, p <0.001), higher score in Barthel index (71.7±SD28.4, p<0.001) with lower baseline burden of functional dependence in one or more daily activities, lower fall risk (17.3 vs 22.4%, p 0.032), and and the long term survival was lower (Figure 2).

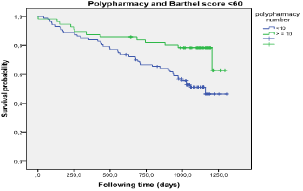

Figure 3: Survival CCP with fall risk and polypharmacy (≥ 10 vs <10).

Figure 4: Survival CCP with Barthel score <60 and polypharmacy (≥ 10 vs <10).

The overall mortality among the CCP people with fall risk was 38.5%. The average survival time was 880.5±357.7 days. In unadjusted analysis, patients who had fall risk were at a significantly higher risk of death if were older ≥80 year-old (42.5% vs 23.3%, p 0.042), ≥4 active medications (52.0% vs 25.0%, p 0.002), cognitive impairment (52.3% vs 26.9%, p 0.002), or Barthel score <60 (53.2% vs 20.4%, p<0.001). The patients with fall risk (Figure 3) or Barthel score <60 (Figure 4) associated to polypharmacy ≥10 active medications had higher mortality, but not with cognitive impairment (Figure 5). We observed a strong association that persisted even after adjustment for known mortality risk factors: age [HR 1.04 CI95 1.02-1.05, p<0.001], Charlson score [HR 1.21 CI95 1.12-1.30, p < 0.001] and Barthel [HR 0.988 CI95 0,985-0.992, p<0.001]. Routine clinical questioning about previous falls may, thus, be a key strategy to identify at-risk individuals, and therefore, preventive interventions can be introduced.

Figure 5: Survival CCP with Cognitive Impairment and polypharmacy (≥ 10 vs <10).

We have found higher percentage of CCP with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor among with fall risk, but without differences (p 0.2211) in mortality risk. The Isolation and loneliness has been shown to be a risk factor for falls. The percentage in our study was 22.3% among people ≥75 year-old.

Discussion

The average use of 9.0 daily medications by our study participants is consistent with existing literature [12,13], but is higher and concerning. This study identified some attributes of the elderly groups most vulnerable to polypharmacy prescribing. On one hand, the clinical status of older individuals with multimorbidity can be further complicated by concomitant geriatric syndromes. The coexistence of chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes has been extensively described in the literature [14] and makes difficult considering one condition at a time. Unfortunately, there is no standard cut point with regard to the number of medications that is agreed upon for the definition of polypharmacy. To operationalize this definition, researchers have arbitrarily chosen various cut points. The 91.6% CCP had ≥4 active medications, 52.4% between 4-9, and 32.9% ≥10. Many studies in ambulatory care define polypharmacy as a medication count of five or more medications.

On the other hand, polypharmacy is not just the use of multiple medications but also and/or the administration of more medications than are clinically indicated, representing unnecessary drug use [15,16]. For this definition, medications that are not indicated, not effective, or constitute a therapeutic duplication would be considered polypharmacy. Although this definition is more clinically relevant, it does necessitate a clinical review of medication regimens. In our study, the therapeutic groups most used are coincident with those commonly involved in inappropriate prescription: treatment of peptic ulcer, cardiovascular medications, antidepressants, and hypnotics [17]. These medications have not coincidence with the cardiovascular conditions more prevalent. We can consider, regardless of the definition of polypharmacy, an increased risk of inappropriate drug use. Future research should document more evidence regarding the adverse impact on total health care costs and patient health outcomes associated to medication errors, poor adherence, drug-drug and drug-disease interactions and, most importantly, adverse drug reactions. The prevalence of inappropriate prescribing in primary care according to the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) is about 39.5% of the medications.

Also this study is one of the few prospective studies to examine the significance of polypharmacy and their association with mortality among elderly individuals identified as CCP. In the analyses of risk for death it seems that, it becomes a factor of higher mortality, but it doesn't happen with the cognitive impairment (Long Rank 0.240). A diagnosis of fall risk or Barthel <60 in people with polypharmacy confers a high risk for mortality. This study confirms the polypharmacy added to conditions as Barthel score <60 or fall risk is associated to increased mortality risk in community and they are a useful indicator to identify subjects eligible for preventive measures in public health strategies. It has been described [18] that these patients are older and suffer poorer functional status at baseline and functional deterioration which could explain the higher mortality. The Barthel score may be useful clinically because it provides a dynamic, integrated assessment of mobility. However, some studies suggest a U-shaped association, that is, the most inactive and the most active people are at the highest risk of falls [19]. 55.2% of CCP with fall risk scored Barthel<60 (moderate dependence). Unfortunately, longitudinal data on functional changes were not measured as part of this study

The decision to prescribe a drug is often based on a specific disease and closely related comorbidities, but has many limitations in older patients, because it fails to take into account age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, coexistence of other acute or chronic diseases, use of multiple drugs, risk of drug-drug or drug-disease interactions, cognitive status, and disability [20,21]. The dosages and effects of medications, beneficial or adverse, are definitely different in the elderly than in younger patients, the latter population being typically and almost exclusively enrolled in randomized clinical trials designed for drug licensing. However, current medical practice guidelines often require multiple medications to treat each chronic disease state for optimal clinical benefit. Therefore, an elderly patient with at least two disease states, such as heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, will usually exceed this arbitrary threshold of >five medications. Limited evidence was found of increased health care utilization and poorer quality of life resulting from inappropriate drug use in the elderly.

The method used to define "fall risk" can be little clear. Epidemiological research into falls and fall-related injuries has been effected by a series of conceptual and methodological problems. Clinicians are often unaware of the many existing scales for identifying fall risk and are uncertain about how to select an appropriate one. The fall may simply be an isolated event and most non-injurious falls (75%-80%) are never reported to health professionals [22]. Given that the majority of falls do not come to the attention of any medical service, the use of the evaluation of the fall risk in the community could improve knowledge translation of into clinical practice. The WHO reported falls account for 40% of all injury deaths [8]. Unfortunately, there are no national bench marks to compare our fall rates. Eventually for risk factor assessment to make a difference, all risk factors identified on the risk assessment need to be addressed in the care plans, and the care plans need to be acted on [23].

Eventually, the antidepressants have long been associated with an increased risk for falls. In our study there was not difference in mortality between patients receiving and those not receiving SSRIs [24], but reducing the number of medications, particularly those that contribute to postural hypotension or sedation, is most often reported as target area for fall reduction. The coordination among clinicians and caregivers and the periodic critical review of all the medications taken, a close relationship with the family, primary care physician and social workers are essential. Well-coordinated information should be provided to the family, spouse, caregiver and all the persons involved in a patient's care, without undermining the patient's autonomy and right to make informed choices

Conclusion

In summary, the 91.6% CCP had ≥4 and the 42.9% CCP had ≥10 active medications and it was associated with a increased risk of mortality if there was associated risk of falling or functional disability (Barthel score <60). The inappropriate prescribing relates to specific therapeutic groups and criteria, which should be targeted in future interventions.

In the coming years it is hopeful that increased research funding will become available for the study of new and innovative interventions to reduce unnecessary drug use. Given the cooccurrence of polypharmacy with poor performance status and multi-morbidity, multi-dimensional interventions are needed to improve health outcomes.

References

- Reeve J Blakeman T (2013) Generalist solutions t complex problems: Generating practice-based evidence-the exemple of managing multi-morbidity. BMC Family Practice 14: 112.

- Kings fund (2012) Long Term Conditions and multi morbidity.

- Guaraldo L, Cano FG, Damasceno GS, Rozenfeld S (2011) Inappropriate medication use among the elderly: a systematic review of administrative databases. BMC Geriatr 11: 79.

- Susan W Muir, Karen Gopaul, Manuel M Montero Odasso (2012) The role of cognitive impairment in fall risk among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 41 (3): 299-308.

- Robert L Maher Jr, Joseph T Hanlon, Emily R Hajjar (2014) Clinical Consequences of Polypharmacy in Elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf 13(1): 5765.

- Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM (2012) Designing health care for the most common chronic condition-multimorbidity. JAMA 307(23): 2493-2494.

- Catalunya (2013) Departament de Salut; TERMCAT, Centre de Terminologia. Terminologia de la cronicitat [en línia]. TERMCAT, Centre de Terminologia cop. (Diccionaris en Línia), Barcelona.

- (2007) WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press. World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 156353 6.

- Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales KL, McKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classyfing prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 40(5): 373-383.

- Pfeiffer E (1975) A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 23(10): 433-441.

- García-González JV, Díaz-Palacios E, Salamea A, Cabrera D, Menéndez A (1999) Evaluación de la fiabilidad y validez de una escala de valoración social en el anciano. Aten Primaria 23(7): 434-440.

- Fulton MM, Allen ER (2005) Polypharmacy in the elderly: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 17(4): 123-132.

- Fiona Clague, Stewart W Mercer, Gary McLean, Emma Reynish, Bruce Guthrie (2016) Comorbidity and polypharmacy in people with dementia: insights from a large, population-based cross-sectional analysis of primary care data. Age Ageing 46(1): 33-39.

- Prados Torres A, Calderon Larranaga A, Hancco Saavedra J, Poblador Plou B, van den Akker M (2014) Multimorbidity patterns: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 67(3): 254-266.

- Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT (2007) Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacothe 5(4): 345-351.

- Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, Valluri S, Briesacher BA (2013) Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 30(5): 285-230.

- Bregnh0j L, Thirstrup S, Kristensen MB, Bjerrum L, Sonne J (2007) Prevalence of inappropriate prescribing in primary care. Pharm World Sci 29(3): 109-115.

- Garcia Morillo JS, Bernabeu Wittel M, Ollero Baturone M, González de la Puente MA, Cuello Contreras JA (2007) Risk factors asociated to mortality and functional deterioration in pluripathologic patients with heart failure. Rev Clin Esp 207(1): 1-5.

- Gregg EW, Pereira MA, Caspersen CJ (2000) Physical activity, falls and fractures among older adults: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc 48(8): 883-893.

- Figueras A (2011) The use of drugs is not as rational as we believe... but it can't be! The emotional roots of prescribing. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67(5): 433-435.

- Steinman MA, Handler SM, Gurwitz JH, Schiff GD, Covinsky KE (2011) Beyond the prescription: medication monitoring and adverse drug events in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(8): 1513-1520.

- González Henares MA, Clua Espuny JL, Queralt Tomas MLL, Panisello Ta- falla A, Ripolles Vicente R, et al. (2016) Falls Risk and Mortality among Chronic Complex Outpatients: Results of Community-Based Prospective Study. Gerontol Geriatr Res 2(5): 1024.

- Patterson SM, Hughes C, Kerse N, Cardwell CR, Bradley MC (2012) Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16: CD008165.

- Thapa PB, Gideon P, Cost TW, Milam AB, Ray WA (1998) Antidepressants and the risk of falls among nursing home residents. N Engl J Med 339(13): 875-882.

© 2018 Muria Subirats E, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)