- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics studies

Cardiac Metastasis in an Asymptomatic Geriatric Female

Kyle Galati BS1, Taral R Sharma2*

1Osteopathic Medical Student, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Spartanburg, SC.

2University of South Carolina School of Medicine - Greenville, Greenville, SC & Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

*Corresponding author: Taral R Sharma, Clinical Assistant Professor, University of South Carolina School of Medicine - Greenville, Greenville, SC & Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC. Greenville, South Carolina, USA

Submission: November 20, 2017; Published: January 23, 2018

ISSN : 2578-0093Volume2 Issue1

Abstract

Tumors metastatic to the heart (cardiac metastases) are among the least known and highly debated issues in oncology, and few systematic studies are devoted to this topic [1]. Cardiac metastases are considered to be rare; however, when sought for, the incidence seems to be not as low as expected [2]. This case presents a 68-year-old female patient with worsening cardiac function and stage 4 lung cancers. The transthoracic echocardiogram revealed mildly diminished left ventricular ejection fraction of 40-45%, as well as a low-density mass noted in the left atrium with the left interatrial septum intact. Later, a transesophageal echocardiogram was performed and it revealed a 3 x 1.5cm mass in the left atrium which was thought to originate from or near the right superior pulmonary vein. While therapy was showing favorable results towards the lung mass, a cardiac mass was eventually discovered, and treatment was limited due to its position and size. This case shows that cardiac metastases may not be as rare as the literature suggests and can be asymptomatic despite the massive loss of efficient contractile material. It may be practical to monitor for cardiac metastases in lung cancer patients to prevent further metastasis and help guide therapy.

Case Presentation

68-year-old female with a past medical history of stage 4 lung cancers diagnosed in March of 2016. She received chemotherapy and implantation of a Mediport with no complications. The CT in March showed a large right lower lobe lung tumor which invaded the right lower lobe bronchi. It showed pleural-based metastatic lesions and left adrenal mass suspicious for metastatic disease. There was also a small pericardial effusion and pericardial and anterior mediastinum and right diaphragmatic metastatic disease. In June another CT was performed and showed overall increase in size of the large right lower lobe lung mass, but it was more cystic in appearance with less of a solid enhancing component. Additionally, there was decreased size of nodularity along the major fissure, anterior and right internal mammary lymph nodes, and left adrenal nodule. The findings suggested favorable response to therapy. In September the patient had a routine CT done to evaluate her response to treatment and the CT revealed continued enlargement of the right lower lobe mass. The nodular enhancing masses within the area had decreased in size as well as decrease in the nodularity along the major fissure. However, there had been a development of a soft tissue mass in the left atrium that was not present previously as well as a slight enlargement of the right hilar lymph nodes. She presented to the Emergency Department after being told that she had an abnormal finding on a CT of her chest. At the time of her presentation to the emergency room, the patient complained of some chronic generalized weakness otherwise denied any chest pain, dyspnea, dizziness, palpitations, fever or chills. Upon examination, there was no leg swelling or calf pain. Her vital signs were 97.3-degree Fahrenheit, blood pressure was 114/62mm of Hg, heart rate of 120 per minute, respiratory rate of 18 per minute and oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. Otherwise, Physical examination was unremarkable.

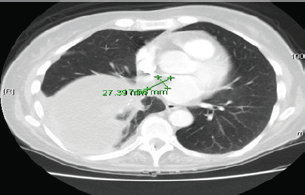

Figure 1:(before).

The patient's family history was significant for her biological father with multiple myeloma and the patient is a former smoker, who quit smoking 10 years ago. The CT scan of the chest with contrast was completed to check on the status of her lung cancer. Her CT scan of the chest (Figure 1) showed enlargement of the right lower lobe mass, soft tissue mass in the left atrium measuring 1.7 x 2.7cm, as well as enlargement of the right hilar node. It was noted that there was possibly a low-density mass within the pulmonary vein into the left atrium. Upon consultation with Cardiology and Oncology it was determined that there was no surgical option and anticoagulation was not recommended. She then continued to follow up with the Oncologist to discuss further chemotherapy (Figure 2).

Figure 2:(after).

Hospital Course

Upon admission, the patient was scheduled for a Stat transthoracic echocardiogram, which revealed mildly diminished left ventricular ejection fraction of40-45%, as well as a low-density mass noted in the left atrium with the left interatrial septum intact. At that time, the patient was started on heparin infusion in case it was caused by a deep vein thrombosis. On day two of the admission, a transesophageal echocardiogram was performed which revealed a 3 x 1.5cm mass in the left atrium which was thought to originate from or near the right superior pulmonary vein.

Pathogenesis

Tumors can spread to the heart through four alternative paths

1) Direct extension

2) Through the bloodstream

3) Through the lymphatic system

4) Intracavitary diffusion through either the inferior vena cava or the pulmonary veins.

Conclusion

Cardiac metastases are among the least known and highly debated issues in oncology, and few systematic studies are devoted to this topic [1]. While they are considered to be rare; however, when sought for, the incidence seems to be not as low as expected [2]. The incidence of cardiac metastases reported in literature is highly variable, ranging from 2.3% and 18.3% [2]. This case shows an incidence of cardiac metastases that could have been found earlier if monitored for. There were no surgical options because of the size and location of the lesion. While asymptomatic at the time of presentation, it is unknown if it will eventually affect the patient in a more significant way. As a metastasis-induced pericardial effusion is quite often the first clinical sign of a malignant tumor, cytodiagnostic examinations can be the first step in patients with no history of neoplasms. The histopathological assessment of pericardial biopsy specimens harvested after thoracotomy is another option [3]. Patients with a metastatic carcinoma ofunknown primary location pose a relatively common clinical problem, and many management and therapeutic aspects should be considered when endeavouring to solve it [4] Neoplastic invasion secondary to lymphoma typically tends to replace the myocardial tissue, and broad heart areas are globally infiltrated by homogenized white- greyish tissue, with the typical "fish meat” appearance [5]. This case shows that cardiac metastases may not be as rare as the literature suggests and can be asymptomatic despite the massive loss of efficient contractile material [6]. Therefore metastatic involvement of the heart and pericardium may go unrecognized until autopsy [7]. It may be practical to monitor for cardiac metastases in lung cancer patients to prevent further metastasis and help guide chemotherapy and possible surgical intervention.

References

- Bussani R, De Giorgio F, Abbate A, Silvestri F (2007) Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol 60(1): 27-34.

- Wenger NK (1992) Pericardial disease in the elderly. Cardiovasc Clin 22(2): 97-103.

- Virmani R (1995) Tumours metastatic to the heart and pericardium. In: Burke A, Virmani R, eds. Atlas of tumour pathology. Tumours of the heart and great vessels. 3rd Series Fascicle 16. Washington, DC: AFIP, USA, pp. 195-209.

- Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, Komorowski J, Bell AK, et al. (2005) Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res 11(10): 37663772.

- Roberts WC, Glancy DL, De Vita VT (1968) Hodgkin's disease, lymphosarcoma, reticulum cell sarcoma and mycosis fungoides. A study of 196 autopsy cases. Am J Cardiol 22(1): 85-107.

- Meng Q, Lai H, Lima J, Tong W, Qian Y, et al. (2002) Echocardiographic and pathological characteristics of cardiac metastasis in patients with lymphoma. Oncol Rep 9(1): 85-88.

- Chiles C, Woodard PK, Gutierrez FR, Link KM (2001) Metastatic involvement of the heart and pericardium: CT and MR imaging. Radiographics 21(2): 439-449.

© 2018 Kyle Galati BS, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)