- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics studies

Understanding the Role of Spirituality and Faith in Relation to Life Expectancy and End of Life Experience in Terminally-ILL Cancer Patients

Leyla F1* and Fatemeh A2

1Department of PhD Health Psychology, Islamic Karaj Azad University, Iran

2Department of Psychology, Aligarh Muslim University, India

*Corresponding author: Leyla F, Department of PhD Health Psychology, Islamic Karaj Azad University, Iran

Submission: September 14, 2017; Published: December 22, 2017

ISSN : 2578-0093Volume1 Issue4

Abstract

Spiritual beliefs and faith are important in the lives of many terminally cancer patients, spiritual beliefs and faith can help patients cope with the emotional experiences of end of life and face death and also influence life expectancy in terminally cancer patients. The spiritual and faith dimensions fuse the essential estimations of terminally cancer patients, their considerations on what gives life meaning and religious or non-religious perspective. It additionally incorporates convictions about what happens after death. The purpose of this literature review was to describe the role of spirituality and faith in life expectancy and end of life experience in terminally Cancer patients. The reviewers searched electronic databases and performed a manual search for studies published. The inclusion criteria covered spirituality and faith for terminally cancer patients in relation to life expectancy and end of life experience. The studies were original, randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental designs. Studies were selected using the inclusion criteria. The results indicate that spirituality and faith produces positive effects on patient's end of life experience and psychological conditions and on increase their life expectancy. Spirituality and faith improve the adjustment and coping strategies with cancer. Further research into the cost effectiveness of spirituality, faith and its long-term effectiveness for cancer suffering is needed.

Keywords: Spirituality; Faith; Life expectancy; End of life experience; Terminally cancer patients

Introduction

Cancer is a devastating disease for millions of people around the world which it ranks among the most feared of all diseases. It is the product of cumulative lifestyle and environmental factors that place everyone at risk. According to estimates from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), there were approximately 12.7 million new cancer cases worldwide in 2008, 5.6 million of which occurred in economically developed countries and 7.1 million in economically developing countries. There were approximately 7.6 million cancer deaths worldwide in 2008, 2.8 million of which occurred in economically developed countries and 4.8 million in economically developing countries. By 2030, the global cancer burden is expected to nearly double, growing to 21.4 million cases and 13.2 million deaths. And while that increase is the result of demographic changes-a growing and aging population-it may be compounded by the adoption of unhealthy lifestyles and behaviors related to economic development, such as smoking, poor diet, and physical inactivity [1].

When cancer is described as terminal it means that it cannot be cured and is likely to cause death within a limited period of time. The amount of time is difficult to predict but it could be weeks to several months. This distressing news can affect you and the people close to you in different ways. There is no right or wrong way to react when you are told your cancer is too advanced to cure. Everyone responds in their own way. For most of patients, this is very shocking news. Some people become silent. They cannot believe what they are hearing and don't know what to say or do. Some start to cry and feel as though they won't be able to stop. Others may become very angry and scared. Some people feel numb and as though they have no emotions. It is natural to feel desperate, upset, angry, or that you don’t believe the news. At times, terminally ill cancer diagnosis will probably feel shock, anger, and sadness.

These emotions can feel overwhelming at times. This news will mean that they can’t plan their future in the way they had hoped. Dying may mean leaving behind family members, and other important people in their life. Patients may wonder how they will cope and won't want to see them upset. These thoughts may be too painful to cope with at times. A number of socio-demographic characteristics are associated with cancer disparities, including income, race/ethnicity, age, sex, and other factors. Some cultural factors may serve to impede cancer outcomes while others may play a protective role. Part of successful coping and survivorship involves impact of the disease on physical and emotional functioning outcomes; spirituality and faith are an integral part of some culture. It has also been noted that spiritual beliefs are related to the cultural background which cultural background assumes an important role in the way people make meaning of suffering and illness, and spirituality and faith may have an impact on how people cope with the illness [2].

Spirituality has been defined in numerous ways. These include: a belief and faith in a power operating in the universe that is greater than oneself, a sense of interconnectedness with all living creatures, and an awareness of the purpose and meaning of life and the development of personal, absolute values. It's the way you find meaning, hope, comfort, and inner peace in life. Although spirituality is often associated with religious life, many believe that personal spirituality can be developed outside of religion. Acts of compassion and selflessness, altruism, and the experience of inner peace are all characteristics of spirituality. The importance of spirituality and faith in coping with a terminal illness is becoming increasingly recognized. Spiritual and faith issues are important for many patients suffering from cancer in terminal stage, and a number of patients would like caregivers to bring up such issues to help to release end of life despair experience and also it gives hope to them to be alive and may improve life expectancy among terminally ill cancer patients. In cancer patients physical burden of cancer, psychological distress, including increased anxiety and depression and poor quality of life, seems to be greater than in the general population, particularly in the later stages of the disease [3].

Therefore in the final stages of many terminal illnesses such as cancer, care priorities tend to the focus often changes to palliative care for the relief of end of life experience such as pain, symptoms, and emotional stress. Anticipating the demands of end of life care giving can help ease the journey from care and grief towards acceptance and healing. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that spiritual beliefs across cultures and faith often include concepts related to prevention, etiology, and treatment of ill-health which may have an impact on health [4-7]. Numerous of terminally ill cancers patients believe that their spirituality and faith help promote healing, especially at an advanced stage of cancer, when medications and other treatments cannot provide a cure for their conditions.

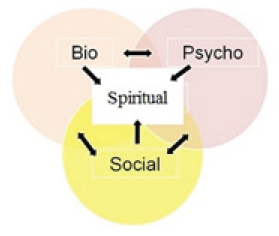

The Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual Model of Care

The fundamental task of medicine, nursing, and the other health care professions is to minister to the suffering occasioned by the necessary physical finitude of human persons, in their living and in their dying [8]. Death is the ultimate, absolute, defining expression of that finitude. George Engel laid out a vast alternative vision for health care when he described his biopsychosocial model. The biopsychosocial is a general model or approach stating that biological, psychological (which entails thoughts, emotions, and behaviors), and social (socio-economical, socio-environmental, and cultural) factors, all play a significant role in human functioning in the context of disease or illness. It posits that, health is best understood in terms of a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors rather than purely in biological terms [9].

This model, not yet fully realized, placed the patient squarely within a nexus that included the affective and other psychological states of that patient as a human person, as well as the significant interpersonal relationships that surround that person. Scientific conception of the patient or how it can be integrated into a more general metaphysics of life and death; furthermore an entire "movement” has arisen promoting the integration of spirituality into medicine. The World Health Organization has declared that spirituality is an important dimension of quality of [10]. Toward this end, some are now calling for a model that goes even further a biopsychosocial-spiritual model of health care [11,12]. An approach that considers the biological dimension of human behavior closely linked with and inseparable from, psychological, social, and spiritual systems is known as the bio-psycho-social-spiritual approach [13]. The bio-psycho-social-spiritual approach applies to the personal dimension and the environmental dimension. The biological, psychological, and spiritual person is a part of the personal dimension. The social structure of a person is a part of the environmental dimension (Figure 1).

Figure 1

For many persons, this spiritual history unfolds within the context of an explicit religious tradition. But, regardless of how it has unfolded, this spiritual history helps shape who each patient is as a whole person, and when life-threatening illness strikes, it strikes each person in his or her totality [14]. This totality includes not simply the biological, psychological, and social aspects of the person [15], but also the spiritual aspects of the whole person as well [16]. This biopsychosocial-spiritual model is not a "dualism" in which a "soul" accidentally inhabits a body. Rather, in this model, the biological, the psychological, the social, and the spiritual are only distinct dimensions of the person, and no one aspect can be disaggregated from the whole. Each aspect can be affected differently by a person's history and illness, and each aspect can interact and affect other aspects of the person.

Terminally Ill Cancer Patient

Terminal illness is a disease that cannot be cured or adequately treated and that is reasonably expected to result in the death of the patient within a short period of time. This term is more commonly used for progress diseases such as cancer or advanced heart disease than for trauma. In popular use, it indicates a disease that eventually ends the life of the sufferer. According to the medical dictionary terminal cancer defined as an advanced stage of a malignant neo-plastic disease with death as the inevitable prognosis. A malignancy expected to cause the Patients death in a short period of time such as weeks to several months. However patients who have cancer may be referred to as a terminal patient, terminally ill. Often, patients are considered terminally ill when their estimated life expectancy is six months or less, under the assumption that the disease will run its normal course. Defining a patient as terminal might provide opportunities to plan the terminal phase [17] that, in the end, could result in a better-quality end of life for the patient and his or her career [18]. It also may lead to problems, such as poor symptom control such as restricted morphine [19-21] or "carer fatigue" caused by insufficient support to the informal carer [22,23].

Chow & Christakis [24-26] and their colleagues have demonstrated most physicians either do not define patients as being terminal or their prognostic estimates tend to be optimistic, Vigano & his colleagues [27] reported particularly with regard to those patients who die soon after the cancer diagnosis. This might affect patients' appropriate and timely referral to specialist palliative care services [28] or can lead to unplanned hospitalization because of poorly coordinated or otherwise inadequate supportive care services being available at home [29].

Patients use information about the expected course of their illness, including how long they are likely to survive, in a variety of ways. It can help them decide whether to take a long awaited trip, which therapies are worth pursuing, what kind of support system they may need as their condition worsens, and how much time they will have to put their affairs in order. Patients often have plans they want to accomplish before they die, and knowing that their time is short may prompt them to attend to such matters. Receiving a terminal prognosis may also open up conversations about death and dying that may be painful at first but can bring considerable relief to patients and family members alike.

Life Expectancy in Terminally ILL Cancer Patients

Upon receiving a diagnosis of a fatal illness like metastatic cancer, Alzheimer's disease or congestive heart failure, many patients ask, "How much time have I got?" It's a reasonable question, given that there is often much to plan for and accomplish before a progressive illness robs patients of their physical or mental abilities. "Accurately predicting life expectancy in terminally ill patients is challenging and imperfect,” "Physicians are typically optimistic in their estimates of patient survival." Every individual reacts to treatment differently, nobody knows in advance how effective cancer treatment will be.

There's additionally no real way to know to what extent anybody will live with or without cancer. Life expectancy experience may be very different; survival rates are only estimates and are based on type of cancer, the stage of cancer when patients were diagnosed, the particular traits of cancer (such as cell types and growth traits), the treatment patients received, patients unique physical and emotional health. Viscomi [30] emphasized that the estimation of life expectancy from the date the diagnosis of cancer is made until death has been performed in many medical fields to generate measures of cancer survival relevant to clinicians, health economists, policymakers, and insurance companies. There is need to estimation of life expectancy for the exploring cancer treatment options, to help patients and their family makes more informed decisions about cancer treatment. Researchers stated that life expectancy is a function of comorbidity, disability, and cancer stage, in addition to age and cancer type [31] and it is too difficult to estimating. In general, survival analysis provides an estimation of the survival rate during the observed study period, but there has been a lack of reliable method for lifetime extrapolation [31]. According to Chaves LJ & Gil CA [32] increased life expectancy and the prospect of longevity lead to reflection on the importance of spirituality while aging. The relationship between spirituality and old age takes place through the capacity to bear the limitations, difficulties and losses inherent to the process; thus, the nature of living a spiritual life was observed to be heterogeneous, while all had in common the recognition of its importance and its significance for living an old age with Quality of Life.

End of Life Experience and Care in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients

Different patients react to the news that they have a terminal illness in different ways. In general, almost all patients go through various stages of acceptance when a disease like cancer has been diagnosed [33]. University of Virginia Health System in 2010 reported the first stage is disbelief. Most people are shocked that it could happen to them, there is extreme anxiety especially about the unknown. Shock, despair and anger are common. There is also guilt that perhaps the person has done something wrong to receive such a diagnosis. Some individuals use humor as a psychological defense mechanism; others become helpless and often start to bargain. This first stage usually lasts from a few days to many months. The second stage is depression, which is usually a reaction to the diagnosis. The depression is mild to moderate in intensity and needs family support. Only in rare cases is any type of medical therapy required. Duration of depression often can last several weeks to throughout the illness. The goal is to help the person go into the final stage of acceptance. In other studies involving patients with terminal cancer, low levels of spirituality have been found to correlate with negative mood states, such as tension, anxious preoccupation, depression, anger, cognitive [34-36], as well as hopelessness and suicidal ideation [37,38] and the desire for a hastened death [39].

Even with years of experience, caregivers often find the last stages of life uniquely challenging. Simple acts of daily care are often combined with complex end-of-life decisions and painful feelings of bereavement. End-of-life care giving requires support, available from a variety of sources such as home health agents, nursing home personnel, hospice providers, and palliative care physicians. In the final stages of life-limiting illness, it can become evident that in spite of the best care, attention, and treatment, patients are approaching the end of their life. The patient's care continues, although the focus shifts to making the patient as comfortable as possible.

Depending on the nature of the illness and the patient's circumstances, this final stage period may last from a matter of weeks or months to several years. During this time, palliative care measures can provide the patient with medication and treatments to control pain and other symptoms, such as constipation, nausea, or shortness of breath. Although most patients with late-stage cancer express a continued will to live even as their health worsens, some express a desire for hastened death. The few studies conducted have suggested that cancer patients’ desire for hastened death is cross sectionals related to a number of psychological and clinical variables, most notably depression and hopelessness, but also to anxiety, pain, performance status, disease stage, quality of life, symptom related distress, and spiritual well-being, with desire for hastened death related to poorer functioning in each case [38-42].

Cleeland [43] & his colleagues (1994) and Danis & Garrett [44] have stated that among adults, the quality of care at the end of life is suboptimal. Lynn [45] & his colleagues (1997), which one study of elderly patients found that there was considerable suffering at the end of life, with up to 25 percent of patients experiencing moderate to severe pain in the last three days of life. Entering the terminal phase of a cancer disease may be clinically recognized by indistinct patterns, such as lack of response to treatment, increased disease progression, the onset of anorexia, or the loss of will to live. By definition, there is no cure or adequate treatment for terminal illnesses. However, some kinds of medical treatments may be appropriate anyway, such as treatment to reduce pain or ease breathing. Fried [46] & his colleagues (2007) have shown that some terminally ill patients stop all debilitating treatments to reduce unwanted side effects. Others continue aggressive treatment in the hope of an unexpected success. Still others reject conventional medical treatment and pursue unproven treatments such as radical dietary modifications.

Patients' choices about different treatments may change over time. Palliative care is normally offered to terminally ill patients, regardless of their overall disease management style, if it seems likely to help manage symptoms such as pain and improve quality of life. Hospice care, which can be provided at home or in a longterm care facility, additionally provides emotional and spiritual support for the patient and loved ones. Some alternative medicine approaches, such as relaxation therapy, massage, and acupuncture may relieve some symptoms and other causes of suffering [47,48]. Care in the palliative care context differs from curative care because it reaffirms life and faces death as a reality to be experienced together with the family members. Its purpose is to improve the patients and relatives’ Quality of Life (QoL) in view of an advanced disease, through the prevention and relief of suffering, pain treatment and valuation of the culture, spirituality, customs and values, besides the desires and beliefs that permeate death [49,50].

Nature and Role of Spirituality and Faith in Terminally 111 Cancer Patients

Spirituality can be defined as "a belief system focusing on intangible elements that impart vitality and meaning to life's events" [51]. Spirituality, a related term, refers to a search for meaning and purpose in life and relationship with a higher power [52] which can but does not necessarily involve religion. Spirituality may be defined by two components, religious well-being (achieving harmony with God) and existential well-being (finding meaning and purpose in one’s life [53]). Therefore spirituality is the relationship individuals have with a power or influence past themselves that helps them feel connected and improve their lives. Faith defined as a person's most deeply held beliefs strongly influence his or her health. Spirituality is a construct that involves concepts of "faith" and "meaning” [5456]. Faith involves a belief in a higher transcendent power, not necessarily through participation in the rituals and beliefs of a specific organized religion.

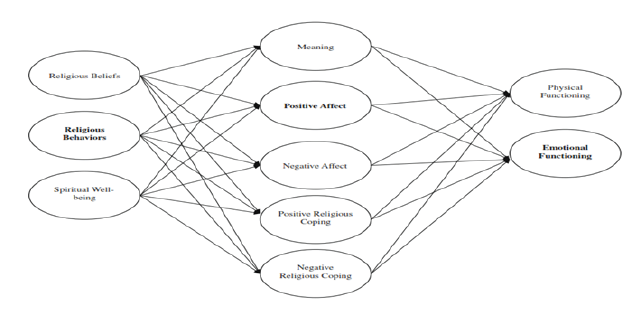

Figure 2: Theoretical model of the religion/spirituality-health connection among cancer patients.

Faith in a transcendent power may identify this power as being external to the human psyche or internalized. It is the relationship and connectedness to this power or spirit (sometimes identified as the soul) that is an essential component of the spiritual experience and is related to the concept of meaning. Frankl's [57] theory emphasizes that an individual's search for meaning can be frustrated. The "faith" component of spirituality is most often associated with religion and religious belief, while the "meaning” component of spirituality appears to be a more universal concept that can exist in religious or non-religiously identified individuals. Religion is a particular situated of beliefs or practices typically associated to an organized group [58] (Figure 2). Research shows that religion and spirituality are associated positively with better health and psychological wellbeing [59-61]. Several previous studies have been conducted examining the role of spirituality among African Americans with cancer. Spirituality was found to increase hope and psychological well-being among African American women with breast cancer [62]. Many patients believe that their spirituality helps promote healing, especially at an advanced stage cancer.

In these patients, spiritual well-being has been found to positively correlate with subjective well-being [63], hope and positive mood states [64,65], purpose in life [66], and overall quality of life [67]. There is both theoretical and empirical support for the positive relation between spirituality/faith and emotional wellbeing. Religious faith also appears to make an objective, measurable difference in the mental health of cancer patients. A few individuals discover spirituality by practicing their religious beliefs, while others find it outside of an organized religion. Researcher stats that frequently individuals come back to the religious conventions of their youth, but others may discover comfort in another tradition, such as meditation. Numerous cancer patients would portray themselves as spiritual, however not so much religious.

Religion and spirituality are constructs adopted to cope with the stress the cancer causes as, for many patients; they can contribute to the relief of suffering and greater hope concerning the QoL [68]. Numerous studies have been carried out internationally of the interaction between spirituality, faith and religious beliefs and health, and the needs of patients for the health service to follow up existential needs [69,70], and also findings are consistent with the possibility that it may be important for health care providers to assess patients' level of spirituality as they attempt to help them deal with the adverse psychological effects associated with facing a chronic illness such as cancer special in final stages. Spirituality and faith can be essential to the well-being of individuals who have cancer, empowering them to better cope to the disease at end of life. Spirituality and faith may help patients and their support system find deeper meaning and experience a sense of self-awareness while terminal stage. Spiritual coping is defined as a process that people utilize to find meaning in stressful circumstances [71].

Spiritual coping can be divided into two broad patterns: positive coping, i.e., a constructive drawing upon spirituality for support and negative coping, i.e., engaging in spiritual struggle and doubt [72,73]. Spirituality often becomes important throughout the course of the disease and its treatment as well as during the period of remission [74] and may be an important coping strategy for patients facing the various stressors associated with cancer as well as its potential life threat. A review on religious involvement and illness coping suggests that religion helps to ease stress [75]. Researcher has reported that spirituality can become more salient to those with cancer [76]. Among individuals with terminal cancer, those who reported more advanced stages of faith had higher quality of life than those at more simple stages of faith [77]. Among cancer patients, prayer is used and found to be helpful, even though it can be sometimes accompanied by religious conflicts such as unanswered prayers [78]. A study of religious coping in patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplants also suggests that religious struggle may contribute to adverse changes in health outcomes for transplant patients [79].

Quality of life has become increasingly important for patients as treatment advances extend the length of survival. One study, involving a random sample of 296 breast cancer survivors in southern California, found that spiritual care was more important to the patients' quality of life than support groups, counseling sessions, or even peer or spouse support [80].

Spirituality and Faith Relation to Life Expectancy and End of Life Experience in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients

Frankl's [81] work focuses on the ability of individuals to find meaning in their life (e.g., finding a life purpose or a sense of life fulfillment and satisfaction), particularly when their life is threatened. Based on Frankl’s [81] theory, cancer may be viewed as a temporal constraint and a catalyst for finding meaning. Whereas he has focused exclusively on the existential domain of spirituality, others have argued that spirituality is a combination of religious and existential dimensions. A meaning-making process may serve as an interpretive framework for patient suffering [82].

Spirituality is a crucial component of individual focused consideration and critical factor path patients with cancer coping strategies to their illness from diagnosis through treatment, survival, recurrence and dying. Many terminally cancer patients are becoming interested in the role of spirituality and faith in their end of life experience and respire, and also health care. This may be because of dissatisfaction with the impersonal nature of our current medical system, and the realization that medical science does not have answers to every question about health and wellness [83] .

Micozzi noted that “the blending of spirituality and faith with the tenets of alternative, complementary, and integrative therapies provides individuals with a means of understanding how they contribute to the creation of their illness and their healing" [84] . Spirituality and faith can give a terminally cancer patients a structure for finding meaning and viewpoint through a source more noteworthy than self, and it can provide a sense of control over sentiments of helplessness. Religious practice supplies the natural social support. Ticiane & his colleagues [85] to compare the quality of life and religious-spiritual coping of palliative cancer care patients with a group of healthy participants; assess whether the perceived quality of life is associated with the religious-spiritual coping strategies; identify the clinical and socio demographic variables related to quality of life and religious-spiritual coping. 192 participants were interviewed who presented good quality of life and high use of Religious-Spiritual Coping. Greater use of negative Religious-Spiritual Coping was found in Group A, as well as lesser physical and psychological wellbeing and quality of life.

An association was observed between quality of life scores and Religious-Spiritual Coping (p<0.01) in both groups. Male sex, Catholic religion and the Brief Religious-Spiritual Coping score independently influenced the quality of life scores (p<0.01). Both groups presented high quality of life and Religious-Spiritual Coping scores. Male participants who were active Catholics with higher Religious-Spiritual Coping scores presented a better perceived quality of life, suggesting that this coping strategy can be stimulated in palliative care patients. In particular, religiosity has been reported to serve as a coping strategy to help manage emotional distress [86], and religious and/or spiritual coping strategies have been found to be helpful in dealing with the emotional impact of cancer in terminal stage [87-89]. Spirituality among cancer patients may be conceptualized as a form of emotion-focused coping, as it is primarily aimed at lessening the emotional distress associated with the disease [90].

Johnson & Spilka [91] reported cancer patients also place a high value on interactions with clergy, noting that pastoral visits and prayers help them maintain hope and optimism. Holland & his colleagues [92] have found a strong relationship between patients' faith experience and the effectiveness of their coping with cancer in end of life. With hopefulness specifically linked to better adjustment by those receiving radiation therapies [93]. Robust hope can provide strength and courage to face the stress of illness and treatment, while hopelessness brings passivity and resignation. Researchers have found a strong link between religious beliefs and hope [94]. In a study of cancer patients at the University Michigan Medical Center, 93 percent said that their spirituality and faith had increased their capacity to be hopeful [95]. Hope enables persons to actively cope with difficult and uncontrollable life situations. Patients with a strong sense of hope report a high quality of life [96]. Some researchers believe that spirituality and faith increases the body’s resistance to stress. In a 1988 clinical study of women undergoing breast biopsies, the women with the lowest stress hormone levels were those who used their faith and prayer to cope with stress [97].

Though cancer can challenge faith, many terminally ill patients ultimately find that their belief system is strengthened by the experience. Cayse [98] in 1994 explored among 29 separate strategies used by cancer patients to cope with end of life experience, prayer was both the most common and most helpful for their cope and adjustment. Hematti & his colleagues [99] stated spiritual well-being in patients with an advanced cancer has been found to positively correlate with subjective well-being, lower pain levels, hope and positive mood states, high self-esteem, social competence, purpose in life, and overall quality of life. In this regard, Quran recitation is stated to be an efficient way to increase patient spirituality and also to handle life's everyday challenges. In other words, a benefit of Quran recitation on outcome of radiotherapy for palliative radiotherapy patients was found.

Consideration and Conclusion

Cancer illness poses a great challenge in sustaining a sense of meaning and purpose in life, as well as not uncommonly precipitating a crisis of spirituality and faith. Being able to maintain a sense of meaning and spiritual well being appears to help terminally ill cancer patients cope better with death and have a better emotionally experience in their end of life. Research indicates that the religious beliefs and spiritual practices of patients are powerful factors for many in coping with serious illnesses such as cancer and in making ethical choices about their treatment options and in decisions about end-of-life care [100,101]. End of life decisions have a huge spiritual component. For most of the patients at an advanced stage cancer, cancer is considered an incurable disease that is related to magic, bad luck or a punishment from God [102,103], which means for some; terminally ill cancer diagnosis has the opposite effect on their sense of spirituality. It makes them doubt their beliefs or religious values, challenges their faith, and can cause spiritual distress. Thus some patients become angry with God for allowing them to get cancer or wonder if they are being punished. Spiritual distress can make it harder for patients to cope with cancer and its treatment. If cancer patients feel this way, it could have a negative effect on their attitude and progress. However, even people who are angry at God or are non-believers might benefit from talking to a spiritual counselor; experts say. Cancer patients in terminal stage tend to focus on religious issues increasingly. When 231 patients with end-stage cancer were asked what maintained their quality of life, their "relationship with God" was the most common response among 28 choices that included "how well I eat,” "physical contact with those I care about," and "pain relief” [104]. Expressing feelings of shaken belief to someone who may be able to help restore faith, or even just understand their anger and doubts can be therapeutic. Also spirituality and faith may help patients and families find deeper meaning and experience a sense of personal growth during terminally cancer stage, while having end of life experience. Researchers emphasized that spiritual practices and faith can help terminally cancer patients to adjust with end of life experience.

Patients who rely on their faith or spirituality tend to experience increased hope and optimism, freedom from regret, higher satisfaction with life, and feelings of inner peace. Also, patients who practice a religious tradition or are in touch with their spirituality tend to be more compliant with end of life experience. Spiritual well-being offers some protection against end-of-life despair in those for whom death is imminent. Barry & William [105] findings have important implications for palliative care practice. Controlled research assessing the effect of spirituality-based interventions is needed to establish what methods can help engender a sense of peace and meaning. It is important to understanding that it would be a serious mistake to think that any spiritual intervention could ever give a dying patient either a sense of dignity or a sense of hope [106]. Rather, the health professions must come to understand that the value and the meaning are already w present as given in every dying moment, waiting to be grasped by the patient. The professional's role is to facilitate this spiritual stirring, not to administer it. There are resources available in the religious and health care community that can help provide guidance and support. Cancer support programs can be particularly helpful in helping cancer patients and their families sustain this sense of meaning and purpose.

The development of specific counseling interventions to sustain meaning and hope for patients with advanced cancer, such as our "Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy" interventions hold promise as tools that can be utilized by Psycho-oncologists in their care of cancer patients as they approach the end of life. Spiritual well-being in patients with an advanced cancer has been found to positively correlate with subjective well-being [107,108], lower pain levels [109,110], hope and positive mood states [111,112], high selfesteem, social competence, purpose in life [113], and overall quality of life [114,115] that helps to terminally ill cancer patients to have better end of life experience.

Spirituality and faith increases psychological well-being by enhancing the availability of social support, improving the relationship with one’s partner, offering a sense of meaning, controllability and predictability to life events, and reducing selffocus and worry while producing a feeling of calmness. Optimism for life is consistent with the latest studies of people with advanced cancer, which found that patients who turn to religion to cope with cancer are more likely to desire life saving measures to prolong their life [116] which optimism may improve life expectancy among terminally ill cancer patients. The most common coping strategy for cancer patients is praying alone or with others, as well as having others pray for them [117]. Although distinct, both are intertwined, as spirituality is considered to be the essence of a person, as if it were a search for meaning and purpose in life, while religiosity is the expression of spirituality itself, through rituals, dogmas and doctrines [118,119].

To summarize, studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between spirituality, faith, and life expectancy, end of life experience. Spirituality and faith, in its broadest sense addresses the meaning patients find in their lives particularly during times of distress, illness and dying [110-115]. Coordinating spirituality and faith as a crucial space of care will result in better end of life experience and improvement in life expectancy for terminally cancer patients. Terminally cancer patients facing death often experience a crisis of meaning. Some cancer patients are significantly comforted by their spiritual beliefs. Others may experience religious struggle or negative ways of coping with illness [115-120].

It is essential for terminally cancer patients that their social, spiritual, and religious beliefs be perceived and coordinated in the advancement of an arrangement of consideration and in choices that are made concerning end-of-life consideration. Respect for patient values and beliefs require competent communication skills in health care professionals [121-125]. Research into the relationship between spirituality/fait and health outcomes and patient well-being is burgeoning. Such work requires that we stay in touch with our own feelings and that which provides meaning and value within our own lives, while working in a profession dedicated to the care of others [126,127].

References

- American Cancer Society (APA) (2015) Global Cancer Burden to Nearly Double by 2030.

- Tzeng HM, Yin CY (2006) Learning to respect a patient's spiritual needs concerning an unknown infectious disease. Nursing Ethics 13(1): 17-28.

- Derogatis L, Morrow G, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetsky S, et al. (1983) The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 249(6): 751-757.

- Ellison CG, Levin JS (1998) The religion-health connection: Evidence theory and future directions. Health Educ Behav 25(6): 700-720.

- Levin JS, Vanderpool HY (1989) Is religion therapeutically significant for hypertension? Soc Sci Med 29(1): 69-78.

- Fredrickson BL (2002) How does religion benefit health and wellbeing? Are positive emotions active ingredients? Psychological Inquiry 13(3): 209-213.

- Ader R, Feiten DL, Cohen N (1991) Psycho-neuroimmunology. (2nd edn), Academic Press, San Diego, California, USA.

- Sulmasy DP (1999) Finitude freedom and suffering. In: Hanson R, Mohrman Hi (Eds.), Pain seeking understanding: Suffering medicine and faith. Pilgrim Press, Cleveland, Ohio, USA, pp. 83-102.

- Engel GL (1977) The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 196(4286): 129-136.

- The WHOQOL Group (1995) The WHO quality of life assessment (WHOQOL) position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci and Med 41(10): 1403-1409.

- King DE (2000) Faith spirituality and medicine: Toward the making of a healing practitioner. Haworth Pastoral Press, Binghamton NY, USA.

- McKee DD, Chappel JN (1992) Spirituality and medical practice. J Fam Pract 35(2): 205-208.

- Hutchison Elizabeth D (2008) Dimensions of Human Behavior: The Changing Life Course. (3rd edn), Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks CA, California, USA.

- Ramsey P (1970) The patient as person. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

- Engel GL (1992) How much longer must medicine's science be bound by a seventeenth century world view? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 57(1-2): 3-16.

- King DE (2000) Faith spirituality and medicine: Toward the making of a healing practitioner. Haworth Pastoral Press, Binghamton, USA.

- Saunders Y, Ross JR, Riley J (2003) Planning for a good death: Responding to unexpected events. BMJ 327(7408): 204-206.

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, et al. (2000) Factors considered important at the end of life by patients family physicians and other care providers. JAMA 284(19): 2476-2482.

- Zenz M, Willweber-Strumpf A (1993) Opiophobia and cancer pain in Europe. Lancet 341(8852): 1075-1076.

- Bercovitch M, Adunsky A (2004) Patterns of high-dose morphine use in a home-care hospice service: Should we be afraid of it? Cancer 101(6): 1473-1477.

- Carr DB, Goudas LC, Balk EM, Bloch R, Ioannidis JP, et al. (2004) Evidence report on the treatment of pain in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 32: 23-31.

- Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, Clinch J, Reyno L, et al. (2004) Family caregiver burden: Results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ 170(12): 1795-1801.

- Visser G, Klinkenberg M, Broese van Groenou MI, Willems DL, Knipscheer CP, et al. (2004) The end of life: Informal care for dying older people and its relationship to place of death. Palliat Med 18(5): 468-477.

- Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, Hudson M, Eychmuller S, et al. (2003) A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 327: 195.

- Chow E, Harth T, Hruby G, Finkelstein J, Wu J, et al. (2001) How accurate are physicians' clinical predictions of survival and the available prognostic tools in estimating survival times in terminally ill cancer patients? A systematic review. Clin Oncol 13(3): 209-218.

- Christakis NA, Lamont EB (2000) Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study BMJ 320(7233): 469-472.

- Vigano A, Dorgan M, Bruera E, Suarez-Almazor ME (1997) The relative accuracy of the clinical estimation of the duration of life for patients with end of life cancer. Cancer 86(1): 170-176.

- Brinckner L, Scannell K, Marquet S, Ackerson L (2004) Barriers to hospice care and referrals: Survey of physicians' knowledge attitudes and perceptions in a health maintenance organization. J Palliat Med 7(3): 411-418.

- Abom B, Obling N, Rasmussen H, Kragstrup J (2000) Unplanned emergency admission of dying patients. Causes elucidated by focus group interviews with general practitioners. Ugeskr Laeger 162(43): 5768-5771.

- Viscomi S, Pastore G, Dama E, Zuccolo L, Pearce N, et al. (2006) Life expectancy as an indicator of outcome in follow-up of population-based cancer registries: the example of childhood leukemia. Ann Oncol 17(1): 167-71.

- Messori A, Trippoli S (1999) A new method for expressing survival and life expectancy in lifetime cost effectiveness studies that evaluate cancer patients (review). Oncol Rep 6(5): 1135-1141.

- Chaves LJ, Gil CA (2015) Older people's concepts of spirituality related to aging and quality of life. Cien Saude Colet 20(12): 3641-3652.

- Pass OM (2006) Toni Morrison's Beloved: a journey through the pain of grief. J Med Humanit 27(2): 117-124.

- Kaczorowski JM (1989) Spiritual well-being and anxiety in adults diagnosed with cancer. Hosp J 5(3-4): 105-116.

- Fehring RJ, Miller JF, Shaw C (1997) Spiritual well-being religiosity hope depression and other mood states in elderly people coping with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 24(4): 663-671.

- Cotton SP, Levine EG, Fitzpatrick CM, Dold KH, Targ E, et al. (1999) Exploring the relationships among spiritual well-being quality of life and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 8(5): 429-438.

- Chibnall JT, Videen SD, Duckro PN, Miller DK (2002) Psychosocial- spiritual correlates of death distress in patients with life-threatening medical conditions. Palliative Med 16(4): 331-338.

- McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W (2003) Effect of spiritual wellbeing on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet 361(9369): 1603-1607.

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Kaim M, Funesti-Esch J, et al. (2000) Depression, hopelessness and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA 284(22): 2907-2911.

- Kelly B, Burnett P, Pelusi D, Badger S, Varghese F, et al. (2003) Factors associated with the wish to hasten death: A study of patients with terminal illness. Psychol Med 33(1): 75-81.

- Jones JM, Huggins MA, Rydall AC, Rodin GM (2003) Symptomatic distress hopelessness and the desire for hastened death in hospitalized cancer patients. J Psychosom Res 55(5): 411-418.

- Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, Mowchun N, Lander S, et al. (1995) Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 152(8): 1185-1191.

- Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Edmonson JH, Blum RH, et al. (1994) Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med 330(9): 592-596.

- Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J (1997) What is wrong with end-of-life care? Opinions of bereaved family members. J Am Geriatr Soc 45(11): 1339-1344.

- Lynn J, Teno JM, Phillips RS, Wu AW, Desbiens N, et al. (1997) Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. Ann Intern Med 126(2): 97-106.

- Fried TR, O'leary J, Van Ness P, Fraenkel L (2007) Inconsistency over time in the preferences of older persons with advanced illness for life- sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 55(7): 1007-1014.

- Grealish L, Lomasney A, Whiteman B (2000) Foot massage. A nursing intervention to modify the distressing symptoms of pain and nausea in patients hospitalized with cancer. Cancer Nurs 23(3): 237-243.

- Alimi D, Rubino C, Pichard-Leandri E, Fermand-Brule S, Dubreuil- Lemaire ML, et al. (2003) Analgesic effect of auricular acupuncture for cancer pain: a randomized blinded controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 21(22): 4120-4126.

- Mi-Kyung S, Mary BH (2017) Generating high quality evidence in palliative and end-of-life care. Heart Lung 46(1): 1-2.

- Provinciali L, Carlini G, Tarquini D, Defanti CA, Veronese S, et al. (2016) Need for palliative care for neurological diseases. Neurol Sci 37(10): 1581-1587.

- Maugans TA (1996) The Spiritual History. Arch Fam Med 5(1): 11-16.

- Jenkins RA, Pargament KI (1995) Religion and spirituality as resources for coping with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 13(1-2): 51-74.

- Paloutzian R, Ellison C (1982) Loneliness spiritual well-being and the quality of life. In: Peplau L, Perlman D (Eds.), Loneliness: A source book of current theory research and therapy. New York, USA, pp. 224-237.

- Puchalski C, Romer AL (2000) Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Med 3(1): 129-137.

- Karasu BT (1999) Spiritual psychotherapy. Am J Psychother 53(2): 143162.

- Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D, et al. (1999) A case of including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology 8(5): 417-428.

- Frankl V (1963) Man's search for meaning. Pocket Books. New York, USA.

- Yonker JE, Schnabelrauch CA, Dehaan LG (2012) The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review. J adolesc 35(2): 299-314.

- Puchalski CM (2001) Spirituality and Health: The Art of Compassionate Medicine. Hospital Physician, pp. 30-36.

- Koenig HG, Larson DB (2001) Religion and mental health: Evidence for an association. International Review of Psychiatry 13(2): 67-78.

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J (2004) Religious Coping Methods as Predictors of Psychological Physical and Spiritual Outcomes among Medically Ill Elderly Patients: A Two-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Health Psychology 9(6): 713-730.

- Gibson LM, Parker V (2003) Inner resources as predictors of psychological well-being in middle-income African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Control 10(5 Suppl): 52-59.

- Reed PG (1987) Spirituality and well-being in terminally ill hospitalized adults. Res in Nurs Health 10(5): 335-344.

- Mickley JR, Soeken K, Belcher A (1992) Spiritual well-being religiousness and hope among women with breast cancer. Image J Nurs Sch 24(4): 267-272.

- Fehring RJ, Miller JF, Shaw C (1997) Spiritual well-being religiosity hope depression and other mood states in elderly people coping with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 24(4): 663-671.

- Cotton SP, Levine EG, Fitzpatrick CM, Dold KH, Targ E (1999) Exploring the relationships among spiritual well-being quality of life and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 8(5): 429-438.

- Peteet JR, Balboni MJ (2013) Spirituality and religion in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 63(4): 280-289.

- McCullough ME, Hoyt WT, Larson DB, Koenig HG, Thoresen C, et al. (2000) Religious involvement and mortality: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol 19(3): 211 - 22.

- Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE (2003) Religion and spirituality. Linkages to physical health. Am Psychol 58(1): 36-52.

- Pargament KI (1997) The psychology of religion and coping: Theory research and practice. Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM (2000) The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol 56(4): 519-543.

- Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB (2005) Religious coping and psychosocial adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 61(4): 461-480.

- Mickley J, Soeken K (1993) Religiousness and hope in Hispanic and Anglo-American women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 20(8): 1171-1177.

- Siegel K, Anderman SJ, Scrimshaw EW (2001) Religion and coping with health-related stress. Psychology & Health 16(6): 631-653.

- Wagner GB (1999) Cancer recovery and the spirit. Journal of Religion and Health 38: 27-38.

- Swensen CH, Fuller S, Clements R (1993) Stage of religious faith and reactions to cancer. Journal of Psychology and Theology 21(3): 238-245.

- Taylor EJ, Outlaw FH, Bernardo TR, Roy A (1999) Spiritual conflicts associated with praying about cancer. Psychooncology 8(5): 386-394.

- Sherman AC, Plante TG, Simonton S, Latif U, Anaissie EJ, et al. (2009) Prospective study of religious coping among patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation. J Behav Med 32(1): 118-128.

- Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D, et al. (1999) A case of including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology 8(5): 417-428.

- Frankl V (1963) Man's search for meaning. Pocket Books, New York, USA.

- Kappeli S (2000) Between suffering and redemption. Religious motives in Jewish and Christian cancer patients' coping. Scand J Caring Sci 14(2): 82-88.

- Steven D, Ehrlich NMD (2011) Ehrlich NMD Solutions Acupuncture a private practice specializing in complementary and alternative medicine Phoenix AZ. Review provided by Veri Med Healthcare Network 2(11).

- Micozzi MS (2006) Fundamentals of complementary and integrative medicine (3ri edn), Saunders Elsevier, St Louis, USA.

- Ticiane Dionizio de Sousa Matos, Silmara Meneguin, Maria de Lourdes da Silva Ferreira, Helio Amante Miot (2017) Quality of life and religious-spiritual coping in palliative cancer care Patients. Sci ELO 25: e2910.

- Koenig H, Cohen H, Blazer D, Pieper D, Meador K, et al. (1992) Religious coping and depression among elderly hospitalized medically ill men. Am J Psychiatry 149(12): 1693-1700.

- Feher S, Maly R (1999) Coping with breast cancer in later life: The role of religious faith. Psychooncology 8(5): 408-416.

- Jenkins R, Pargament K (1995) Religion and spirituality as resources for coping with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 13(1-2): 51-74.

- Lamdan R, Taylor K, Seigel J O'Connor B, Moran B (1997) Coping strategies in African American women with breast cancer. Psychosomatics 38: 179.

- Dunkel-Schetter C, Feinstein L, Taylor S, Falke R (1992) Patterns of coping with cancer. Health Psychol 11(2): 79-87.

- SC Johnson, B Spilka (1991) Coping with Breast Cancer: The Role of Clergy and Faith. J Relig Health 30(1): 21-33.

- Holland JC, Passik S, Kash KM, Russak SM, Gronert MK, et al. (1999) The role of religious and spiritual beliefs in coping with malignant melanoma. Psychooncology 8(1): 14-26.

- Christman N (1990) Uncertainty and adjustment during radiotherapy Nurs Res 39(1): 17-20.

- koopmesiners l, Post-white j, Gutknecht s, Ceronsky c, Nickelson k, et al. (1997) How healthcare professionals contribute to hope in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 24(9): 1507-1513.

- Roberts JA, Brown D, Elkins T, Larson DB (1997) Factors influencing views of patients with gynecological cancer about end-of-life decisions. Am J of Obstet Gynecol 176(1 Pt 1): 166-172.

- Ferrell BR, Grant MM, Funk BM, Otis-Green SA, Garcia NJ (1998) Quality of life in breast cancer survivors: implications for developing supportive services. Oncol Nurs Forum 25(5): 887-895.

- Steven D, Ehrlich NMD (2011) Solutions Acupuncture a private practice specializing in complementary and alternative medicine Phoenix AZ. Review provided by Veri Med Healthcare Network.

- Cayse LN (1994) Fathers of children with cancer: a descriptive study of the stressors and coping strategies. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 11(3): 102-108.

- Hematti S, Baradaran-Ghahfarokhi M, Khajooei-Fard R, Mohammadi- Bertiani Z (2015) Spiritual well-being for increasing life expectancy in palliative radiotherapy patients: a questionnaire-based study. J Relig Health 54(5): 1563-1572.

- Puchalski CM (2001) Spirituality and Health: The art of compassionate medicine. Clinical Perspectives in Complementary Medicine, pp. 30-36.

- McCormick TR, Hopp F, Nelson-Becker H, Ai A Schlueter, JO Camp JK (2012) Ethical and Spiritual Concerns Near the End of Life. Journal of Religion Spirituality and Aging 24(4): 301-313.

- Sheikh I, Ogden J (1998) The role of knowledge and beliefs in help seeking behaviour for cancer: A quantitative and qualitative approach. Patient Educ Couns 35(1): 35-42.

- Sandelin K, Apffelstaedt JP, Abdullah H, Murray EM, Ajuluchuku EU (2002) Breast surgery international--breast cancer in developing countries. Scand J Surg 91(3): 222-226.

- McMillian SC, Weitzner M (2000) How Problematic Are Various Aspects of Quality of Life in Patients with Cancer at the End of Life? Oncology Nursing Forum 27(5): 817-823.

- Colleen S McClain, Barry Rosenfeld, William Breitbart (2003) Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet 361(9369): 1603-1607.

- Sulmasy DP (2000) Healing the dying: Spiritual issues in the care of the dying patient. In: Kissel J, Thomasma DC (Eds.), The health professional as friend and healer. Georgetown University Press, USA, pp. 188-197.

- Reed PG (1987) Spirituality and well-being in terminally ill hospitalized adults. Res Nurs Health 10(5): 335-344.

- Yanez B, Edmondson D, Stanton AL, Park CL, Kwan L, et al. (2009) Facets of spirituality as predictors of adjustment to cancer: Relative contributions of having faith and finding meaning. J Consult Clin Psychol 77(4): 730-741.

- 108. Yates JW, Chalmer BJ, St James, Follansbee P, McKegney MFP (1981) Religion in patients with advanced cancer. Medical and Pediatric Oncology 9(2): 121-128.

- Borneman T, Ferrell B, Puchalski CM (2010) Evaluation of the FICA tool for spiritual assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 40(2): 163-173.

- Mickley JR, Soeken K, Belcher A (1992) Spiritual well-being religiousness and hope among women with breast cancer. Image J Nurs Sch 24(4): 267-272.

- Fehring RJ, Miller JF, Shaw C (1997) Spiritual well-being religiosity hope depression and other mood states in elderly people coping with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 24(4): 663-671.

- Cotton SP, Levine EG, Fitzpatrick CM, Dold KH, Targ E (1999) Exploring the relationships among spiritual well-being quality of life and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 8(5): 429-438.

- Unantenne N, Warren N, Canaway R, Manderson L (2013) The strength to cope: Spirituality and faith in chronic disease. J Relig Health 52(4): 1147-1161.

- Phelps A, Maciejewski P, Nilsson M, Balboni T, Wright A, et al. (2009) Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA 301(11): 1140-1147.

- Soderstrom KE, Martison IM (1987) Patients' Spiritual Coping Strategies: A Study of Nurse and Patient Perspective. Oncol Nurs Forum 14(2): 41-46.

- Park CL, Masters KS, Salsman JM, Wachholtz A, Clements AD, et al.(2017) Advancing our understanding of religion and spirituality in the context of behavioral medicine. J Behav Med 40(1): 39-51.

- Richardson P (2014) Spirituality religion and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 3(3): 150-159.

- Santrock JW (2007) A Topical Approach to Human Life-span Development (3rd edn), McGraw-Hill, St Louis, USA.

- McKee DD, Chappel JN (1992) Spirituality and medical practice. J Fam Pract 2(201): 205-208.

- Repetto L, Comandini D, Mammoliti S (2001) Life expectancy comorbidity and quality of life: the treatment equation in the older cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 37(2): 147-152.

- Coping with terminal cancer. University of Virginia Health System, Virginia, USA.

- Hill PC, Pargament KI (2003) Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. Am Psychol 58(1): 64-74.

- Sawatzky R, Ratner PA, Chiu L (2005) A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Social Indicators Research 72(2): 153-188.

- Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J (2003) Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin 129(4): 614-636.

- Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A (2010) Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: A review. Psycho-Oncology 19(6): 565-572.

- Koenig HG (2004) Religion Spirituality and Medicine: Research Findings and Implications for Clinical Practice. South Med J 97(12): 1194-1200.

- Thoresen CE (1998) Spirituality health and science: The coming revival? In: Roth-Roemer S, Kurpius SR (Eds.), The emerging role of counseling psychology in health care. WW Norton. New York, USA, pp. 409-431.

© 2017 Leyla F, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)