- Submissions

Full Text

Forensic Science & Addiction Research

Protection of Children from Sexual Violation: Adequacy of the Contemporary Legal Framework in Sri Lanka

M A D S J S Niriella*

Department of Public and International Law, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka

*Corresponding author: M A D S J S Niriella, Department of Public and International Law, Attorney-at-Law, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka

Submission: February 26, 2018;Published: April 10, 2018

ISSN 2578-0042 Volume3 Issue2

Abstract

It is often stated that children are the soul and the future of a nation. Protection of children is one of the main responsibilities of adults today. Children in Sri Lanka are vulnerable to sexual violence than other forms of violence. Sexual violence against children has become a social issue in the country. Children are prey for sexual violence due to their tender age, immaturity and dependency. They are subjected to sexual violence both in and outside of their home. In many instances, the perpetrators are known to the child victim. According to the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) records, the total number of sexual violence cases against children has increased in the recent past. There is no doubt that children should have a right to protection from sexual violence. This protection can be ensured initially through prevention by adjusting socio-economy set up and where sexual violence has already committed, putting an end to impunity as well as providing assistance to the victimized child. A strong legal framework is utmost important in this regard. The purpose of the paper is to critically evaluate the efficacy of the existing laws and enforce mechanisms in Sri Lanka against child sexual violence. The qualitative research method is adopted, engaging in a desk review referring to the legislations in this regard.

Keywords: Child; Sexual violence; Protection

Introduction

It is a common fact that children are more susceptible than adults to various forms of violence; physical, psychological, sexual violence etc., due to their tender age and immaturity. As scholars such as S Goonasekera, say children are more exposed to sexual violence than other forms of violence1 . According to her, children cannot understand the gravity of this harmful situation precisely including the repercussions of such situations2 . They need the support of adults to handle those situations properly and correctly due to their tender age. Prior to 1990’s, sexual violence against children was not discussed publicly in our society3 . With the adoption of the Convention on Child Rights (CRC), many jurisdictions, including Sri Lanka being signatory to the Convention, started revisiting and amending the existing laws to align with the standards acknowledged in CRC in relation to the protection of children from violence4 . Legal provisions pertaining to protection of children from sexual violence were introduced by the legislations such as Penal Code (Amendment) Act No 22 of 1995, Penal Code (Amendment) Act No 29 of 1998, Evidence (Special Provisions) Act No 14 of 1995, Evidence (Special Provisions) Act 32 of 1999, Child Protection Authority Act No 50 of 1998, Convention on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Women and Children for Prostitution Act No 30 of 2005, Prevention of Domestic Violence Act No 34 of 2005, Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses Act No 04 of 2015 have been passed from 1995 to-date. However, it is seen that the reported incidents of sexual violence against children have increased in Sri Lanka5 . This has raised a concern on the adequacy of the prevailing legal framework regarding the protection of children from sexual violence. It also suggests a need for an effective legal framework to ensure the protection of children from sexual violence. The purpose of the paper is to evaluate the adequacy of the contemporary laws and the efficacy of the enforcement mechanism pertaining to protection of children from sexual violence6 .

- Foot Note

1Goonasekera SE (1998) Children law and justice: a south Asian perspective, Sage Publication, India, p. 96.

2Ibid.

3Ministry of Health Care and Nutrition (2008) National report on violence and health submitted to world health organization, Switzerland, p. 11.

4Marasinghe N (2016) Effective protective mechanisms for the victims of child abuse: need for effective legislative framework to meet with contemporary challenges. Judicial Service Association (JSA) Law 4: 148-149.

5Crime Statistics (2017) Department of Police.

6 It should be noted that the author is engaging a separate review of the Domestic Violence Law in Sri Lanka, presently. Therefore, the present article does not focus on the efficacy of the said Legislation.

7Statistics. Department of Census and Statistics Sri Lanka.

8Ibid.

9Gunaratne C (2005) Property ownership and inheritance rights of women for social protection: the Sri Lanka experience, centre for women’s research and international center for research on women in Ramani Jayasundere, Understanding Gendered violence 2245Voice Against Women In Sri Lanka: A Background Paper for Women Defining Peace 2.

Prevalence of Sexual Violence Incidents against Children

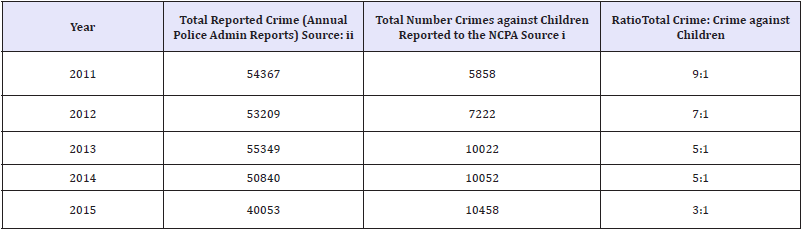

The total population of Sri Lanka as at the end of 2015 was 21 million out of which 7 million were persons who are under 18 years . That statistics indicate, 1/3 of the total population consists of persons who are under 18 years7 - children8 . According to many sources, the prevalence of sexual violence against children in Sri Lanka has increased during the last decade. Further, it indicates, children between 10-14 years are more vulnerable to sexual offences. Statistics of Table 1 demonstrate that there is an increase of violence against children, including sexual violence during the last five years. It also exemplifies that the ratio between the total number of crime and violence against children has been reduced from 9:1 to 3:1 during the period from 2011 to 2015. It demonstrates the increase in violence against children. However, some scholars9 are of the view that generally, the statistics available in the official crime reports do not reflect the reality and many incidents are remained unreported.

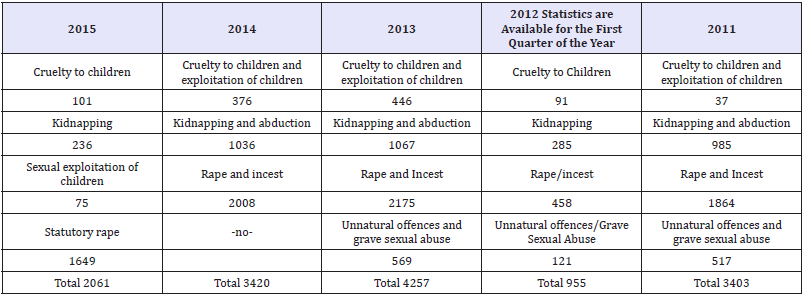

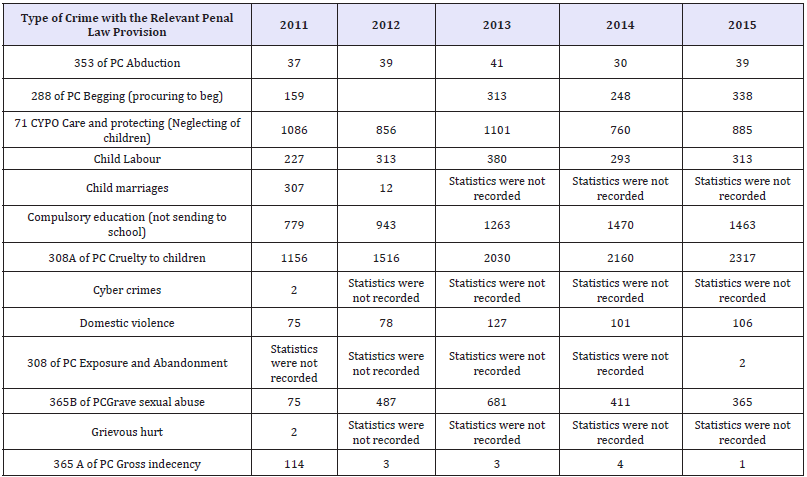

According to the NCPA information and police statistics, (Table 2 & 3) children in Sri Lanka are more vulnerable to sexual offences such as statutory rape, grave sexual abuse, sexual harassment, incest, gross indecency, obscene publication, publications of sexual abuse and sexual exploitation. According to police crime statistics, statutory rape and incest contributed 80% of total reported violence incidents in 2015. It was 58% in 2014, 51% in 2013, 47% in 2012 and 54% in 2011. This demonstrates that at least 50% of the total number of violent incidents occurred against children were sexual violence during 2011-2015. This situation reveals that sexual violence against children is a social issue in Sri Lana and measures should be taken to protect the children from sexual violence. As said earlier, it further suggests a need for law reforms and new enforcement mechanism to protect children from sexual violence.

Table 1: Total crime incidents reported: Crime incidents against children reported to NCPA from 2011 to 2015.

Source i: National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) Data relates to the crimes against children 2011-2015,

Source ii: The annual police administration report issued by the department of police 2011-2015.

- Foot Note

1010Article 34 of CRC.

1111Section 2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act No 28 of 1998 states that child abuse means an offence committed under section 286 A, 288, 288A, 2888B, 308 A, 360 A, 360B, 360 C 363, 364A, 365 , 365 a , 365 B of the Penal Code.

1212 Section 39 of NCPA Act stipulates that any act or omission relating to a child which would amount to an infringement of section 286 A, 288, 288A, 2888B, 308 A, 360 A, 360B, 360 C 363, 364A, 365 , 365 a , 365 B of the Penal Code, violation of the provisions of the Employment of Women and Young Persons and Children Act, breach the provisions in the Children and Young Persons Ordinance, contravene any regulation relating to the Compulsory Education made under the Education Ordinance, and Employing a child in arm conflict which is likely to endanger the child’s life or harm such child physically or emotion come under the purview of child abuse. The interpretation clause (section 39) of NCPA Act defines child as a person who is under 18 years of age.

Table 2: Grave crime abstract from 2011-2015.

Source: Statistics. Department of Police, Sri Lanka, 2011-2015.

Table 3: Crimes committed against children from the period 2011 -2015 Based on the type of the crime.

Source: Statistics (2016) NCPA.

- Foot Note

13Garner AB (1999) Black’s Law Dictionary, (7th edn), West Group.

14Article 1 CRC.

15Section 2 (1989) Age of Majority Act No 17.

16Ibid section 3.

17ICCPR Act No 56, Domestic Violence Act No. 34 of 2005 the two statutes which accept the best interest of a child is of paramount importance with regard to any child affair.

Definition of Some Terminology

Definition of sexual violence

In Sri Lanka, sexual violence is a non-legal term, however, encompasses all types of sexual crimes. Generally, sexual violence against children means any sexually related act which happens between an adult and a child. It can take the traditional form of rape, incest, prostitution, pornography and gross indecency etc.. Further, it may occur through sexting (sending sexually related messages or posting such images through digital devices) through electronic and social media. Therefore, sexual violence against children may occur both in the real physical world and in the digital world. Common feature of these two groups of crimes is that they include penal sexual behavior towards children. The broad definition of sexual violence against children includes hands-on and hands-off sexual abuse. Hands–on sexual abuse requires physical contact between the adult perpetrator and the child victim (e.g. rape, incest) while hands-off sexual abuse does not require physical contact between the perpetrator and the victim (e.g. watching child pornography, exhibiting sexual acts). Often, hands-off sexual abuse may extend to hands-on (physical) sexual violence.

‘Child sexual violence’ is also not defined in any penal statute in Sri Lanka and not even the term ‘child abuse10’ or child sexual abuse. However, the Code of Criminal Procedure Amendment Act No 28 of 199811 and National Child Protection Authority Act (NCPA ACT) No. 50 of 1998 listed several offences under child abuse. More offences are listed in the latter than former12.

Definition of child

Generally, ‘child’ refers to a person under the age of majority, the threshold of adulthood as recognized in law. In Black’s Law Dictionary ‘child’ means a person who has not reached the age of 14, which may be varied from jurisdiction13 to jurisdiction . This definition refers the English Common position. In Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), a person who is under age eighteen is defined as a child14 . In Sri Lanka, eighteen years, is considered as the legal age of majority15 . It does not construe to prevent any person under eighteen years from attaining his/her age of majority at an early age by operation of Law16 . A close review of the statutory law in respect of child affairs demonstrates the inconsistency in defining the term ‘child’.

Several statutes have been enacted in relation to child affairs in Sri Lanka. Children and Young Persons Ordinance No 48 of 1939 (CYPO) which focuses juvenile justice, defines child as a person who is under fourteen years while a young person is defined as a person between the age fourteen and sixteen. This reveals that according to CYPO, persons who are between sixteen and eighteen years are considered as adults for the purpose of criminal liability. Similar definition is given Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children Act, No 8 of 2003. According to the Penal Code (Amendment) Act No 22 of 1995, National Child Protection Authority Act No. 50 of 1998, Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children Act No 8 of 2003, Convention on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Women and Children for Prostitution Act, No 30 of 2005 and Assistance to Protection for Victims of Crime and Witnesses Act No 4 of 2015, define ‘child’ as a person who is under eighteen years. It demonstrates the inconsistency in definition of ‘child’ in our statutory law. The negative effect of this inconsistency will be discussed in later part of this paper.

Free From Sexual Violence as a Human Right

Constitutional provisions

The present Constitution of Sri Lanka, the supreme law of the country which came into force in the year 1978, guarantees, the freedom, equality and fundamental human rights for all the people in the country as an intangible heritage that safeguards the selfesteem, security and welfare of the people in the country. Chapter III of the Constitution (Article 10-17 of the 1978 Constitution) guarantees the fundamental rights of the citizens of the country. The Article 11 acknowledges the right to freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Any sexual act occurs between a child and an adult, itself is a torture against the child due to the ill consequences (physical, mental, health etc.) of such act. In this context, free from sexual violence is a fundamental right of a child, which could be regarded within the ambit of the Article 11.

- Foot Note

18Article 1.

19Age of Majority (Amendment) Act No. 17 of 1989.

20Except Muslim Law.

21Prior to 1995, the age for statutory rape was 12. Muhanmadu Lebe vs Muhamadu Tamby (1901) 2 Browne’s Rep 307.

22In Sri Lanka child marriages are legally accepted under Muslim Law.

23Section 363 (e) of the Penal Code.

24Section 15.

25Sections 4(1) and 66.

26Section 22.

27Section 365 of the Penal Code Amendment Act No 22 of 1995.

28Section 365 A of the Penal Code Amendment act No 22 of 1995.

29The King vs Ana Sheriff (1941) NRL 169; The King vs Marthelis (1942) 43 NLR 560; The King vs Themis Singho (1944) 45 NLR 378; The King vs Basnayake (1948) 49 NLR 414 CAA; King vs Athukorala (1948) 50 NLR 256 CCA where the court held that evidence to prove resistance is essential.

30Rajaratne vs AG Anuradahapura HC No.28/94 / CA No. 19/94 in 1996; Premadasa vs State (2000) 2 SLR 385 AC; Inoka Galage vs Kamal Addararachchi (2002) 1 SLR 307.

According to the Article 12 of the Constitution, all people are equal before the law and they are entitled to the equal protection of the law (Article 12.1), and no person in the country should be discriminated on the difference of their sex, religion, race or caste or ethnicity, language, political opinion or their place of birth etc. (Article 12.2). It further says that the particular Article does not prevent any special legislative measures made or executive actions taken for the wellbeing of children, women and disabled people. According to the Chapter VI (Article 27-29), which focuses on Directive Principles of State Policy and Fundamental Duties, it is a prime duty of the policy makers to take necessary measures to ensure the freedom, welfare, protection of the people in the country without any discrimination. Within this context, the State should have the responsibility to take all the necessary measures, including special legislative measures to ensure that children are free from sexual violence as a right, to give effect to the fundamental chapter of the Constitution.

Children’s charter

Sri Lanka has ratified CRC in 1991. As a result, in 1992, Sri Lanka introduced the Children’s Charter, the first policy document relating to the protection of the rights, safety, welfare and interest of the children in line with the standards acknowledged by the CRC. Though there is no binding force on this charter, it provides guidance/directions in policy making and bringing legal reforms in this connection. The best interest of the child (Article 3)17 , equality (Article 2. 1) and non-discrimination (Article 2.2) are the main principles adopted by the Charter.

Protection from kidnapping, (Article 11), abduction and sale (Article 35), neglect (Article 20), sexual exploitation (Article 34) and torture (Article 36) are some of the specific rights guaranteed for children in this Charter. Further, Children’s Charter recognizes the right to life as an intrinsic right of a child. As argued previously, any sexual act with a child falls within the ambit of torture against the child. Therefore, right to be free from such acts can be considered as a human right guaranteed for children under this charter.

Domestic Penal Legislations

Penal code (Amendment) Act No 22 of 1995

The criminal law of Sri Lanka consists of a variety of penal legislations, chief of which is the Penal Code Act No 02 of 1883. The Penal Code Amendment Act No 22 of 1995, perhaps the most remarkable amendment introduced to the principal statute. The Parliament has passed this amendment, for the special purpose of protecting women and children, who are more vulnerable to any form of violence especially, sexual violence. Although, this amendment introduced some legal measures to protect children from sexual violence, the gray areas which still remain impede achieving its main goal and directing the necessity for further reform.

According to CRC, child means a person who is below eighteen years unless the law applicable to the child considers any different age for the purpose of attaining the age of majority18 . In Sri Lanka, the legal age, for the purpose of age of majority19 , and to make a will/give consent to enter into a marriage bond20 is eighteen years. Therefore, a question arises as to whether a girl child between sixteen and eighteen years who is unable to enter into a marriage bond legally and who has not reached the age of majority, can give legally valid consent for sexual intercourse. This situation creates a gray area in our law and negatively effects the protection of a child.

According to the present law, sexual intercourse between a man and a girl who is under the age of sixteen years is considered as statutory rape21 and consent of the girl is immaterial. Thus, age of sixteen years is identified as the legally accepted age to express the consent for sexual intercourse. This is subject to the exception where the girl is over twelve years of age (though she is less than sixteen years) and the wife of the man and who is not judicially separated from him22 . Marital rape is not considered as a criminal offence in Sri Lanka except the situation where the woman is judicially separated from her legal spouse23 . There may be instances where the girl who has entered into a marriage bond, but separated from her husband. The law relating to marital rape or statutory rape does not provide any protection for such girls.

The present law relating to marriage creates a contradiction with the law relating to statutory rape. The age of marriage (marriageable age) was raised to eighteen years for both male and females by the Registration of Marriage (Amendment) Act No 18 of 199524 and the Kandyan Marriage and Divorce (Amendment) Act No 19 of 199525 . However, according to the Registration of Marriage (Amendment) Act No 12 of 1997, parental consent is required for the marriage of a male or female who is under eighteen years of age. It reveals that a child who is under the age of eighteen years may enter into a legally valid marriage bond with the consent of his/her parents and it has continued to remain despite the above mentioned Act, No. 18 of 199526 . According to subsection 4(2) and (3) of the Kandyan Marriage and Divorce Act, cohabitation for one year upon reaching eighteen years and giving birth to a child can grant validity to the marriage. However, according to the present Kandyan marriage and divorce law, any such marriage, which is not solemnized, is invalid (section 3(1b). Under this backdrop, an accused who is criminally liable for statutory rape can register the marriage with parental consent of the child victim, to overcome legal consequences of statutory rape. Further, such registration of marriages will encourage perpetuation of child marriage and child pregnancy, which leads to the creation of other social issues.

According to the Penal Code, rape is gender specific offence committed against a woman. Anal or oral sexual assaults to a boy child can be adjudicated under unnatural offences27 or acts of gross indecency between persons28 . However, these sections do not provide the protection for a boy child who is between the age of sixteen and eighteen. Further, boys between age sixteen and eighteen who are being subjected to these offences probably could be convicted as co-offenders and could be punished.

Prior to 1995, rape was interpreted as an offence committed against the will of a woman. The resistance made by the victim was important to both parties to prove the existence of the will of the woman. There was a rule of practice that made independent corroboration29 mandatory to prove that there was a resistance from the rape victim. The present law clearly states that evidence of resistance such as physical injuries to the body is not essential to prove that the particular act took place without her consent (363 e ii of the Penal Code). Therefore, now it is established in our law, that it is not mandatory to submit evidence relating to physical injuries of rape victims to corroborate the testimony of the prosecutrix30 . However in practice, there are many instances where the judges look for corroborative evidence which go to the extent of proving the resistance made by the victim. The situation where the first information belated and there is no medical evidence (as an independent corroborative evidence) to prove the resistance, the rape victim may not get any justice. This practical inference pushes the child victim of rape (between the age 16 and 18) to a vulnerable situation.

Abortion is a criminal offence in Sri Lanka (section 303 -307 of the Penal Code). According to this law, abortion is permitted only for the purpose of saving the life of the woman31 . This rigid law negatively affects on a girl who has been pregnant as a result of rape. The rape victim should take the responsibility to look after the child to whom she gave birth32.

Section 364 (A) of the Penal Code defines incest33 as ‘sexual intercourse with another, who is full blood or half blood relative and adoptive parents. This provision applies to both male and female victims and either males or females may be considered perpetrators. However, this section does not distinguish child victims from the adult victims.

According to section 364.2 b of the Penal Code, custodial rape against children is a punishable offence. However, the burden of proof lies with the prosecution, like other criminal matters. Prosecution should prove beyond any reasonable doubt, that the rape incident took place at the place where the child was in custody. In practical terms, it is hard for the prosecution to prove the case as the perpetrator often is an administrator or staff member of the institution where the custody is provided.

Grave sexual abuse was introduced as a separate criminal offence by the 1995 amendment. According to section 365 B34 any sexual activity which does not amount to the offence of rape is considered as the offence of grave sexual abuse. Consent of the victim is not a relevant factor to prove mens rea when the victim is a person who is under sixteen years of age. The punishment imposed for the offence of grave sexual abuse varies according to the age of the victim. The minimum term of imprisonment is five years and may extend to twenty years. If the victim is under sixteen years of age, the minimum imprisonment period is seven years35 , which may extend to twenty years and the consent given by the victim is irrelevant. This distinction provides a lesser protection for the child victim who is between 16 and 18 years.

Children and young person’s ordinance No 48 of 1939

The Children and Young Persons Ordinance (CYPO) provides for the procedure to be followed by all Courts and other law enforcement agencies in dealing with children who are at conflict with the law. According to section 4 (1), any Magistrate Court can function as a Juvenile Court and it has the jurisdiction to hear and determine any case in which a child or young person is charged with any offence except the offences of murder, culpable homicide, attempted murder attempted culpable homicide and robbery. Logically, if a perpetrator is a child who is under the age of sixteen years and has alleged to have committed statutory rape or grave sexual abuse, such a child falls within the purview of CYPO and therefore will be entitled to the benefits of the juvenile justice procedure. However, in practice children alleged of committing such offences are indicted in the High Court. Some instances they are victims of the circumstances who need care, protection, guidance, supervision and rehabilitation rather than punishment.

- Foot Note

36Section 109 (1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure Act No. 15 of 1979.

37Section 109 (4) (a) of the Code of Criminal Procedure Act No. 15 of 1979.

38Section 109 (5) (a) of the Code of Criminal Procedure Act No. 15 of 1979.

39Section 120 of the Code of Criminal Procedure Act No 15 of 1979.

40After 1995 the court has accepted the validity of information and communication technology related evidence/ computer generated evidence/computer related evidence; Abubucker Vs. Queen 54/566 and- Kularathne and others Vs. Rajapakha 1985 1 SLR 24.

41(2002) 1 SLR 307, Further see Premasiri vs The Queen 77 NLR 85; Sunil and Other vs The Attorney General 1986 1 SLR 230; Ajith vs The Attorney General CA Case 212/2003, HC Ampara 725/2002; Jinapala Sumathipala and two others vs The Attorney General CA Case No 09/2013, HC Anuradhaura Case No 59/2007.

Enforcement Mechanismt

Establishing a special investigations police unit

With the influence of the Charter, the National Child Protection Authority Act No. 50 of 1998 was enacted to address the issues related to child affairs. As a result, in the year 1999, the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) (section 2.1) which consisted of local monitoring and child protection committees was established to address the issue of crime commissions against children in the country, especially child abuse matters (section 14). A Special Investigations Police Unit, which functions under the Deputy Inspector General of Police - Crimes and Operation, was established at the NCPA in 2002 to deal with the criminal cases including sexual violations committed against children. In addition to the aforementioned Police Unit, Children & Women Bureau Desks are operating in some police divisions in the country. Having the special skills and knowledge to deal with children is not a mandatory requirement under this Act. Lack of resources, including infrastructure facilities and lack of police officers who are having the special skills to deal with this special category of victims (child victims) made the implementation of the procedure minimal.

Code of criminal procedure Act No 15 of 1979

The law of criminal procedure of Sri Lanka is set out in the Code of Criminal Procedure Act (Cr.P.C) No. 15 of 1979. The principal Act has been amended several times from 1979 to date. The laws relating to conducting criminal trials in Sri Lanka is still based on the traditional adversarial system.

The law relating to the investigation of a crime is set out in Part V, Chapter XI – section 108-125 of the Cr.P.C. The police investigation commences after receiving information (the first information) about a commission of an offence36 or otherwise when a police officer has reason to suspect the commission of an offence37 or to apprehend a breach of peace38 . The first information can be lodged by the primary victim or any person on behalf of the primary victim. With regard to crimes committed against children, the complaint is logged by a parent or a guardian of the child. The police investigation is concluded39 when the proceedings are constituted.

In the practical scenario, the victim has to go to the police station to file the first information. Although a Children and Women Bureau is established in some police stations (not all the police stations), it was observed that police officers are not professionally trained to deal with these victims. There is no such provision in any penal statute to make the training of the officers mandatory. None of the police stations in Sri Lanka are equipped with either trained police officers or infrastructure facilities to interact with child victims. This situation has a negative effect on child victims.

Section 120 of Cr. P.C states, every investigation should be completed without unnecessary delay. The term ‘unnecessary delay’ is unclear as far as the minimum and maximum period that the police can take to conclude the investigation is concerned. These offences are indictable offences and can only be tried in the High Court. It was observed that long periods were taken to complete investigations on many child abuse cases. It was also observed that cases are pending for long periods in the AGs Department too.

Generally, the victims of sexual crimes are referred to the government hospital for the medical examination (section 122 Cr.C.P). These medical examinations are important as forensic evidence at the trial. Further, these examinations help to detect the bad health condition/ailment of the patient, which requires medical attention. In such medical examinations, as the first step, the Government Medical Officer should get the medical history of the patient where the victim has to repeat the same story of the incident to the Medical Officer. According to the police, even though the victims are children they are not given priority, if there is no threat to their life, and are made to wait many hours in the hospitals with the police who accompanied such child victims. Lack of the required facilities to conduct such medical examinations mentioned above and lack of the technical knowledge and skills of the Government Medical Officers-Medico-Legal are the other added ill-factors. Laws relating to the conducting of the investigation (Chapter XI of the Cr.P.C) or the statute enacted to protect the rights of the victims of crime (section 3 (e), 4 & 24 of the Assistance to and Protection of the Victims of crime and Witnesses Act) do not address these issues.

Evidence ordinance No 14 of 1883

The law relating to testifying by a witness and the admission of evidence in a criminal trial are governed by the Evidence Ordinance No. 14 of 1895. Prior to Evidence (Special Provisions) Act No.14 of 1995, computer evidence were not admissible40 . This amendment can be considered as the turning point of the beginning of the admissibility of video evidence. Evidence (Special Provisions) Act No.32 of 1999 introduced two developments with regard to testifying by a child witness in child abuse matters. They are the admissibility of pre-recorded video evidence and allowing a child to testify without causing oath or affirmation. After Evidence (Special Provisions) Act No.32 of 1999, pre recorded interviews with a child witness (victim) (audio or video recordings) in a child abuse matter is admissible as evidence (163 A 1) without calling the child to give evidence in person. When a video recording is tendered to the courts, the child witness should not be examined in chief on any matter related to the recorded testimony (363 A 3). However, the child should be available for cross examination (363 A 2). According to section 120.2.1, unsworn testimony of the child is not inadmissible /invalidated merely because of the reason that such testimony was not given under oath. It means the child can give evidence at the cross examination stage without giving any oath. However, when the child faces cross-examination, the child is definitely being psychologically affected as s/he will be bringing back to memory the nostalgic experiences s/he has had at the time of commission of the crime.

In any criminal matter against a child, the prosecution should prove the evidence beyond any reasonable doubt as it is the common standards of the burden of proof of a criminal case. Therefore, corroboration of the principal evidence by supportive evidence originated from an independent source plays a vital role in any criminal case. Often, in these cases the first information is not being lodged, soon after the incident. In such situations it is unavoidable to prevent delay in referring the child for video recording. Further, much valuable /important evidence may not exist when the child is referred to the medical examination due to this delay and thereby the principal evidence cannot be corroborated by the medical evidence. This leads to a question of the credibility of the witness and credence of the evidence. Therefore, mechanism to empower the child victim or provide the child with more support in the justice process is essential. The traditional judicial attitude in relation corroborating the testimony of the rape victim is also not in favorable for the victim for example: Inoka Gallage v Addaraarachchige Gulendra Kamal Alias Addaraarachchi41 (2002 1 SLR 307).

Convention on preventing and combating trafficking in women and children for prostitution Act No 30 of 2005

The Act No 30 of 2005 prohibits range of activities connected to employing children in commercial sex trade42 . The government demonstrated increasing efforts by establishing new antitrafficking units under the police department. However, Sri Lanka has not been successfully achieved the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking due to various reasons including the following weaknesses in the Act.

a. The child victims of trafficking (those who are arrested for exploitation in commercial sex) are housed in government detention centers where the juvenile offenders are kept-in

b. No special care service is provided for child victims of trafficking

c. Officials are not adequately train to identify the victims.

Punishment and Compensation

Generally, in Sri Lanka there is no sentencing policy as to determine the most appropriate degree of punishment on the offender. The Penal Code (Amendment) Act, No 22 of 1995 introduced the concept of minimum mandatory sentencing rule in respect of all sexual offences43 in order to send the message of deterrence44 . However, in practice, offenders are sentenced with a suspended term of imprisonment. In many cases the court held that the minimum mandatory sentence in Section 364(2) (e) of the Penal Code is in conflict with Articles 4(c), 11 and 12(1) of the Constitution. Marmba Liyanage Rohana alias Loku vs The Attorney General45 and Ambagala Mudiyanselage Samantha Sampath vs The Attorney General46.

Awarding compensation to the victim was subjected to the discretion of the sentencing judge prior to 199547 . An amendment enacted in 1995 made compensation mandatory for sexual offences48 . Further, the Victim Protection Act, enacted in 2015 made compensation as a right of any victim of crime. However, clear criterion for compensatory scheme/mechanism is not specified in this Act.

Conclusion

Although as a formal response, the Parliament of Sri Lanka has put some efforts into protecting children from sexual violence, these efforts are not adequate to provide meaningful protection for them. Therefore, reforms should be introduced to improve the law in this subject to protect the children from sexual violence.

- Foot Note

42Sections 2 (1) and (2). According to the Act, who keeps, maintains or manages places for commercial sex trade or knowingly finances or takes part in the financing for committing of the offence of trafficking of women and children for prostitution, knowingly lets or rents, a building or other place or any part thereof for the purpose of trafficking of women and children for prostitution or any matter connected there to, should be guilty of an offence under this particular Act. Furthermore, any person who attempts to commit or aids or abets in the commission of any offence under this Act, or conspires to commit an offence under this Act should be guilty of an offence under this Act.

43Rape-section 364, trafficking - section 360C, Incest- section 364A and Grave Sexual Abuse section 365 B.

44Proviso of the section 364 (2) of the Penal Code Amendment Act No. 22 of 1995.

45SC Appeal No. 89 A /2009, SC Spl LA 02/2009, High Court Anuradhapura Case No. 149/2003./p>

46SC Appeal No. 17/2013, SC Spl LA No. 207/2012 CA No. 297/2008 HC. Kurunegala No. 259/2006.

47Section 17 of the Cr PC; Rabo vs Silva 32 NLR 91.

48Inoka Gallage v Addaraarachchige Gulendra Kamal Alias Addaraarachchi 2002 1 SLR 307.

© 2018 M A D S J S Niriella. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)