- Submissions

Full Text

Forensic Science & Addiction Research

The Scale of Evil-Interjudge Reliability and Associations with Predictor Variables

Eva Lindström1, Mikael Olausson2, Bengt Persson2, Eva Tuninger3 and Sten Levander4*

1Department of Neurosience, Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden

2Forensic Psychiatric Clinic, Sweden

3Department of Clinical sciences, Lund University, Sweden

4Department of Criminology, Malmo University, Sweden

*Corresponding author: Sten Levander, Department of Criminology, Malmö University, S-20506 Malmö, Sweden

Submission: March 16, 2017; Published: March 23, 2018

ISSN: 2578-0042 Volume2 Issue5

Abstract

Background: The concept of Evil has only rarely been the subject of empirical studies, which in turn requires a distinct definition of the concept, schemes for operationalization and development of measurement tools. The Scale of Evil (SoE) was constructed 1993 but has not yet been studied empirically.

Aim: The main aim was to assess the reliability of the SoE. A second aim was to explore the correlation pattern between SoE and a range of other characteristics of perpetrators of crime. This might shed light on how Evil is construed in the minds of forensic professionals, and laymen.

Method: 139 forensic psychiatric patients (stratified selection) were scored according to SoE by two independent raters. Psychopathy and HCR-15 (risk assessment) scores, as well as a data on a wide range of other individual characteristics were available for most of the subjects.

Results: The interjudge reliability was very high with respect to rank order (tau=0.94) as well as distribution of scores (almost identical). Among more than 100 individual characteristics, one variable displayed a particularly strong association with SoE scores: Lack of Compassion (tau=0.49). As expected SoE correlated with PCL scores, but actually stronger with a diagnosis of Antisocial Personality Disorder, and item H1 (previous violence) and H8 (early behavioural problems) of the HCR-15. Significant associations were also obtained with many other variables, in line with expectations.

Conclusion: SoE is a highly reliable scale. The pattern of associations with the other individual characteristics verifies the importance of psychopathic characteristics when scoring SoE, but SoE goes beyond being" another psychopathy scale". The Compassion variable, with its roots in criminological theory, appears to be a key to understand how raters construe Evil and rate SoE. The strong association qualifies as a construct validation of the SoE scale.

Keywords: Evil; Scale of evil; Criminality; Violence; Forensic; Psychopathy; Risk assessment

Introduction

Some years ago, Knoll [1] wrote about Evil and warned in strong words for inviting Evil into forensic science, particularly the project to develop a "Depravity scale" by Welner [2], who later rebutted eloquently to Knoll's arguments [3]. Knoll claimed that Evil is an exclusively religious concept created by man (a non-essentialist and value nihilistic position) and therefore incompatible with science. This is definitely not a view that is unanimously shared among philosophers or for that matter anthropologists and sociologists. The process of natural selection and survival of the fittest may be viewed as a purely mechanistic process, still, the concept of evil may be built into humans in a way that Jung conceptualized as the "collective unconscious"-and is "objective" in that sense. It is reproducible and has causal power; a concept discussed by the philosopher Harre [4], over a wide range of individuals, settings and cultures. In that sense there may be a universal (human- linked) definition of evil, transcending, at least to some extent, determination by social and cultural factors [5]. If so, it is worth exploring by science. A placard with a citation from Thurstone "If something exists it can be measured" was taped on the door to Hans Eysenck’s office at the Maudsley Institute of Psychiatry. We agree on that as well as the inversion: "If something can be measured reliably and in a non-trivial way, it probably exists".

In the academic context, views of mental illness began to change 200 years ago, but was expressed in religious terminology for at least 50 more years (the degeneration theory driven by Original Sin and own and ancestors' personal sins). Marx & Darwin are the main actors in the process that slowly loosened the religious dominance with respect to the concept of evil and the nature of mental illness, summed up by Lombroso [6]: L’huomo delinquente. Since his time and particularly over the last four decades there have been distinct advances in research within neuroscience as well as ethology (Lorentz' "Das sogenannte Bose"), psychology and sociology, of relevance to the old concept of evil [7]. In particular, rating scales have been constructed to measure risk for violent acts [8], traits of psychopathy [9,10], Depravity [2] and Evilness [11,12].

Stone [12] is a New York-based psychiatrist with psychodynamic training. His interest in understanding murder cases was the starting point for the development of this 23-step Scale of Evil (SoE). In addition to murder, the scale exemplifies scale steps with reference also to other crimes, for instance serial rapes. Stone constructed his scale on the basis of psychodynamic theory (particularly the concept of narcissism), psychopathy and his own clinical cases as well as case descriptions in mass media of persons known to have been exceptionally cruel to a partner, to children, or to other family members.

The concept of excessive selfishness has been recognized throughout history, in ancient Greece labelled as "hubris". In 1911 Otto Rank published the first psychoanalytical paper regarding narcissism, linking it to vanity and self-admiration [13]. Kohut [14] and Kernberg [15] have contributed most to the current analytical understanding of narcissism, but from different points of departure. According to Kohut [14] the environment is the major cause of problems for such persons and there is no separate inborn and problematic aggressive drive. The "grandiose self" reflects the "fixation of an archaic but 'normal' primitive self" while for Kernberg [15] it is a pathological development of the aggressive drive, different from normal narcissism. Michael Stone appears to be more sympathetic vs Kernberg's views but also refers to Kohut's concept of 'narcissistic rage’.

Narcissistic traits are a main characteristic of psychopathy but can occur also among others, e.g., in Asperger’s syndrome [16], or among persons with strong paranoid traits, whether a personality disorder or a psychosis. The "Dark Triade" also includes core psychopathic traits such as superficial charm, grandiosity, pathological lying, lack of remorse or guilt, lack of empathy, and a failure to take responsibility for one’s actions are relevant as well as impulsivity, sexual promiscuity, poor behaviour control, and a parasitic lifestyle. Finally, for the offenders who get the highest scores, sadistic traits are considered [17]. The essence of sadism, as the term was used in DSM-III, is the feeling of enjoyment in hurting others, to infer humiliation, exercise control and administer unproportional punishment. A person can be sadistic without being psychopathic and a person can be psychopathic without being sadistic.

In the SoE, psychopathic traits are included in most of the definitions from a rating score of 9 and upwards, 22 being the high end of the scale. Some of the item definitions have their roots in the psychopathy literature from the 1970ies and onwards [18]. Reference is made to the Psychopathy Checklist [19], based on Cleckley [20] and the first empirical studies using a scale to assess psychopathic traits [9,21].

Personality traits as well as behavioural manifestation are considered in the SoE scale. Individuals showing extreme egocentricity, or narcissism with ruthless disregard for the rights, needs and feelings of others are personality features particularly salient for obtaining high SoE scores. In spite of the heterogeneity of personality and behavioural characteristics which define the components of evilness, the SoE is presented as a uni-dimensional ordinal scale. This might work if humans are equipped with an intuitive understanding of specific latent concept-"evilness". Then, all kinds of evil manifestations can be mapped onto a single dimension, in approximately the same way for a large majority of individuals. This issue boils down to the never-ending discussion between essentialists and value nihilists. If empirical data strongly suggest that a one-dimensional evilness scale yields consistent and meaningful data-it is intriguing for philosophers as well as for anthropologists and neuro-scientists. Value nihilists would have difficulties to explain the finding.

This study is unique by filling a void between empirically oriented behavioral science, on one hand, and psychoanalytic/ humanistic science on the other. The back-ground of the void is the historical and sometimes fierce battle between biological/ constitutional and the psychological conflicts oriented views concerning causes of mental disorders. In addition, the Nazi view of the biologically based racial differences among people made science back-off from biological explanations of individual differences. With this came large differences in methodology among different scientific traditions. Initially we tried to publish the present findings in a psychoanalytical journal-it was rejected because of "too much statistics". It is note-worthy that the present study is the first SoE one to be published, almost 30 years after its presentation. By this we hope to break a ban.

Aims

The first aim of the present study was to investigate the distinctness of the concept of evil, as conceptualized in the SoE. Two raters, of different sex, age, professional training and background, independently rated 139 forensic psychiatric cases. If inter-rater reliability turns out to be good it suggests that the one-dimensional approach is valid and that the concept is sharply defined and independent of certain individual characteristics of the raters. Reliability, in the present context, reflects two aspects of agreement-that the rank-order of the 139 subject with respect to evilness is similar for the two judges (a correlation issue), and that the distribution of evilness scores is similar (a non-bias issue). The second aim of the study was to link evilness scores to a large set of individual characteristics in order to determine which of these characteristics, or combination of characteristics, that maximized the association with rated evilness. We were particularly interested in scores of the Psychopathy checklist and HCR-20 [22] actuarial and clinical risk factor scores. If SoE is another psychopathy checklist, it is trivial. If not, we wanted to explore the connotation of evilness.

Method

Subjects

Eligible subjects were all patients (N=850) subjected to a court- ordered forensic psychiatric assessment at the Department of the Forensic Psychiatry (Malmo University Hospital U-MAS), during the years 1992 to 2006. Among those, 120 patients were selected to obtain a reasonably representative set of all forensic assessments according to the following principles:

1) Index crime-violent/non-violent (most patients committed violent crimes)

2) Enough patients who committed arson and sexual crimes (over-sampling)

3) Whether the patient was on remand or not (over 80% are remand patients assessed as inpatients, non-remand patients are assessed as out-patients).

4) Diagnosed as suffering from a serious mental disorder or not (a concept defined in the Swedish penal code, which is substantially wider than the "Not Guilty Reason Insanity" clause of the legal code of other countries)-around 45% of the cases are assessed as suffering from such a disorder.

The actual selection of the patient material was done by a secretary at the clinic, who was informed about the principles of the selection but otherwise did it himself, without any intervention from the researchers. In addition, 19 Swedish forensic patients who took part in another study were included, the After Care patients [22]. These patients were released from compulsory treatment at the clinic during the years 1998 to 2002, subjected to a very detailed assessment at that point in time, and were then followed with new assessments each half year for two years, and then finally after five years.

Among the included patients there were 19 women and 120 men. Age varied from 15 to 72 with a mean age of 35. Sixty percent were Swedish-born, 13% had West European background, 17% East European, 8% Middle East and 2% other origin.

The scale of evil (SoE)

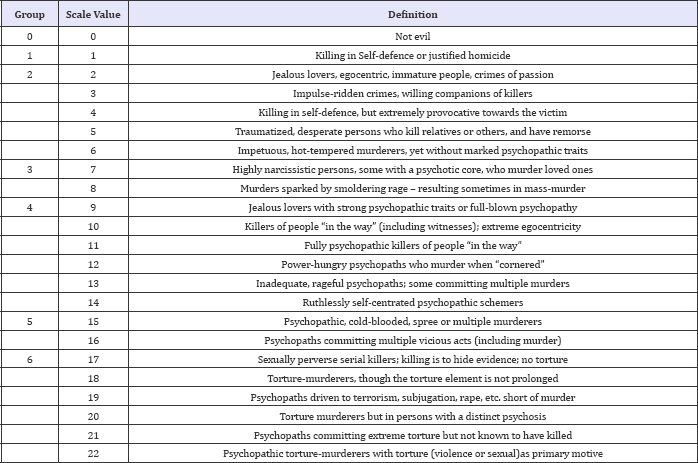

The SoE makes it possible to rank-order persons with respect to evil along a uni-dimensional scale with 23 scale steps. Persons who are not judged to be evil are scored 0. The SoE scale step definitions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: The scale of evil- short definitions of the six groups of increasing evilness, and associated scale steps.

SoE rating procedure

The evilness scoring was formally limited to a case history file data. No interviews were performed but many of the cases were known to both or one of the raters. All available material was used, i.e., the set of forensic assessments (usually two, a pretrial investigation and a detailed full assessment), previous and actual sentences, and hospital case records of the patients. A Swedish forensic assessment is produced as a team-work involving four professions; a forensic psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker and a nurse, and usually summarizes three weeks of 24 hours observations and many interviews.

The two raters (EL and MO) had different training and based their ratings on somewhat different information sets. EL had trained rating technique by using the scale on other forensic patients according to the instructions and case-reports presented by Stone in text and case-vignettes [17]. MO had, as an assistant nurse and also a student of philosophy, participated in the care and had personal knowledge of many of the patients.

Psychopathy ratings

Psychopathy ratings (done routinely at the Forensic Psychiatric Clinic) were available for 112 of the 139 patients. Some patients were rated using PCL/SV, some by PCL/R and a few as part of an HCR-20 rating (scored 0,1 or 2 for item H7 (psychopathy), no raw scores available). In the following, SV scores were transformed to R scores, and R scores used as a graded estimate of psychopathy. Based upon these scores, subjects were scored (ad modum item H7 of HCR-20) as 0 (scores under 20); 1 (scores between 20 and 29); and 2 (scores from 30 and upwards). Fifty-six percent were scored 0; 32% were scored 1 and 12% scored 2 (psychopaths).

HCR-20 risk assessment ratings

HCR-20 [8] ratings for actuarial (H) and Clinical (C) risk factors were done routinely at the Forensic Psychiatric Clinic from 1998 and onwards and were available for 105 of the 139 patients.

Other information

A large set of data were collected according to the EuRAX protocol - a comprehensive clinical risk assessment. In addition to items commonly found in other risk assessment and management instruments, the operationalization of many variables is expressed in line with modern integrated criminology as described by Wikström [23] and suggested by Silver [24]. The instrument can be downloaded from this home page: www.mindstoit.se.

Statistics

Standard statistical procedures were employed using SPSS 22.

Ethics

The study is covered by a general approval concerning research during the actual years on patients cared for at the Forensic Psychiatric Clinic in Malmo, and for the AfterCare patients [22] by the Ethics committee of the Lund university.

Results

Interjudge reliability

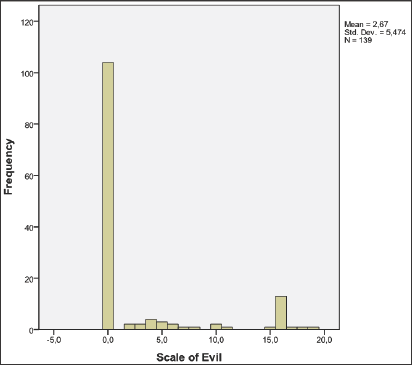

Figure 1: The distribution of evilness scores for the two raters.

The distribution of evilness scores for the two raters is shown in Figure 1. The highest score was 19 for one rater and 17 for the other. There was no significant difference between the distributions (χ2 test) and a remarkably high inter-judge correlation for the full range (0.94, Kendall's tau because of the skewed distribution), and still a very high correlation if subjects who got score 0 by both raters were excluded (tau=0.89). Viewed as shared variance (even if the distribution does not allow parametric statistics) around 85% of the total variability is shared between the raters. The scores of the two raters were averaged and then classified as SoE Group data, ranging from 0 to 6 (Table 1) for the following analyses.

EuRAX variables

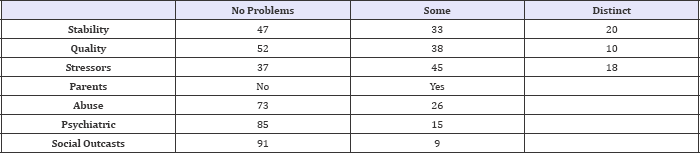

Table 2: Childhood adverse conditions, percentages.

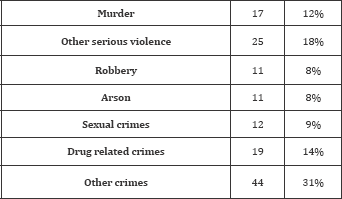

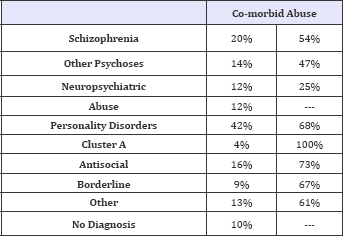

The childhood background of the patients was scored with respect to three dimensions: stability, quality and stressors (Table 2) . The index crime (salient categories) is listed in Table 3. Of those, 106 were crimes involving violence. In addition to the index crime, 59% of the patients were sentenced for other crimes at the time of the index crime. 24 patients (17%) were free of violent crimes (life-time, as far as we know). Among the patients 40 had only one sentence (the index crimes), 29 of them at a later age than 25. Fifty- four had more than three previous sentences. Onset of criminality was before age 25 for 45 of them. The diagnoses of the patients are presented in Table 4. The most notable finding is the high frequency of co-morbid abuse, in almost all diagnostic categories. Suicide thoughts, plans and actual suicide acts were common. At least one act was reported by 33%, repeated acts by 13%. Acts of self-harm without suicide intent was reported by 19%. The rate of victimization was also high: 33% of the patients had been abused by close relatives, 15% by acquaint and 30% had been abused by strangers. The violence of the patients had been directed towards close relatives in 46% of the cases, towards acquaints in 41% of the cases and towards strangers in 53% of the cases.

Table 3: Index crime of 139 patients who underwent a forensic psychiatric assessment at U-MAS

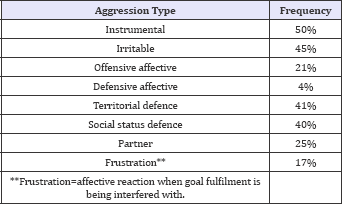

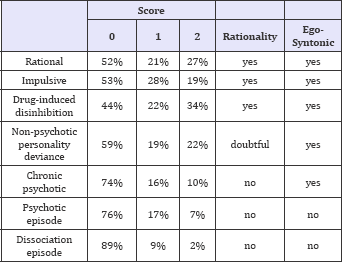

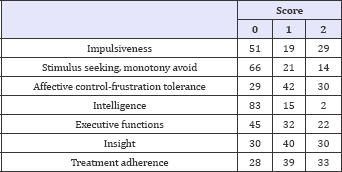

The base rate with respect to the kind/motivation of violent acts is displayed in Table 5. As can be deduced from the percentages, multiple types were common among the patients who had at least one significant criminal act of violence. The base rate reflecting certain attributes of the criminality is shown in Table 6, rated ad modum PCL/R. The corresponding base rates for various personality/ cognitive indices (poor self-control in criminological theory) are displayed in Table 7. The integrated criminological theory combines the social bonds theory with the poor selfcontrol individual attribute [25]. In addition to the factor of being socialized into another culture, the social bonds theory specifies four dimensions which are predictive of criminal propensity. In the present context, three of these are relevant: attachment, commitment and conscience/belief in the conventional order. Attachment and Commitment are covered by two variables. Belief is covered by one index reflecting compassion (other aspects of conscience, including capacity for guilt and shame requires an interview and were not assessed).

Table 4: The main diagnosis (DSM-IV) of 139 forensic psychiatric patients, and comorbid abuse.

Table 5: Percentages of types of aggressive criminal acts among 139 forensic patients, a person may be characterized by more than one type of aggressive acts.

Table 6: Percentages of certain attributes of the cumulated criminal history of 139 forensic patients; Scores 0,1,2 are of the PCL/R type (increasing fit).

Table 7: Percentages of problems reflecting self control functions; Scores 0,1,2=increasing problems.

Associations between SoE and PCL/HCR-20 data

Explorative bivariate data analyses were run using Cross-tables with χ2 and Kendall's tau as statistics. SoE scores were strongly (p<.001) associated with Psychopathy, and the following HCR-20 items: H1 (+, previous violence), H7 (+, psychopathy) and H8 (+, early behavioural problems). Weaker but significant associations were obtained for H2 (+, violence starting early), C2 (+, negative attitude), C3 (-, psychotic symptoms), C4 (+, impulsivity) and C5 (+, difficult to treat). A stepwise linear regression analysis using these items as predictors of SoE suggested that somewhat less than 30% of the variance of SoE was explained by three variables: Psychopathy, H1 and C3 (with reversed sign).

Associations between SoE and EuRAX variables

An explorative bivariate data analysis was run using Crosstables with χ2 and Kendall’s tau as statistics. SoE scores were strongly (p<0.001) associated with a diagnosis of Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD), and lack of Compassion (the strongest association of all). Weaker but significant associations were obtained for Schizophrenia (-), Instrumental violence (+), Territorial defence (+), Defence of social status (+), Suicide (-), Rationally motivated crimes (+), Impulsive crimes (+), Psychotic crimes (-), Cognitive-Executive failure (-), and having an identified enemy as one component of paranoid delusions (+).

What is compassion?

The association with psychopathy suggested that only around 15% of the variance of the SoE scores were determined by psychopathy. The correlation with the Compassion item was considerably stronger (tau=0.49), suggesting that the shared variance was at least double as large as for psychopathy and actually stronger than for any combination of the other variables. This raises the issue of predictor variables of Compassion. Lack of Compassion correlated equally strong (tau=0.34) with Psychopathy and ASPD. A step-wise regression analysis selected six predictors of lack of Compassion, all with positive sign except H6, explaining around 45% of the variance: H2 (early onset of violence), having pleasureable phantasies about violence, Rational criminality, H6 (psychotic illness), Lack of Attachment and Defence of social status as motive for violence.

Discussion

The most striking finding is the almost complete agreement between the two raters with respect to the correlative and the bias issues of the evilness ratings, in spite of their background differences. Evilness, as conceptualized and operationalized in the SoE appears to be a robust one-dimensional concept, but it should not be so because the information which it is based on is complex and multi-dimensional. Indirectly this supports a philosophical/ essentialist position with respect to the concept of Evil. We recognize it when we are confronted with it. Among more than 100 individual characteristics, one variable displayed a particularly strong association with SoE scores, actually stronger than any combination of the other variables: Lack of Compassion.

Scores higher than 8 on SoE are defined with reference to clinical characteristics of psychopathy. As expected SoE scores were correlated with PCL scores, but actually stronger with a diagnosis of Antisocial Personality Disorder, and item H1 (previous violence) and H8 (early behavioural problems) of the HCR-15. Significant associations (- for reversed signs) were also obtained for Schizophrenia (-), Instrumental violence (+), Territorial defence (+), Social status defence (+), Suicide (-), rationally motivated crimes (+), Impulsive crimes (+), Psychotic crimes (-), Cognitive-Executive failure (-), and having an identified enemy as a paranoid delusion (+). Thus, SoE goes way beyond being "another psychopathy scale”. The Compassion variable appears to be a key to understand how the assessors construe Evil and rate SoE. The strong association qualifies as a construct validation of the SoE scale: measuring two different entities, which are only linked according to a theory, by different measurement techniques and obtaining a strong covariation.

What, then, is Compassion? There is a renewed interest in this concept in modern criminology as one aspect of conscience, under the umbrella concept "Belief in the conventional social order”, which in turn is studied because it is strongly associated with a low crime rate on the individual level [23,25-27], and possibly amenable to treatment. Obviously, psychopaths have little compassion for others by being callous and unemotional as well as narcissistically grandiose (cf item definitions of the PCL/R scale). However, antisocial traits as defined in the DSM diagnostic criteria of ASPD as well as the HCR-15 item H2 (young at onset of violence) suggest that norm violations, and particularly violent ones, are equally strong correlates of Lack of Compassion. As expected one high-level criminological index-poor Attachment (social/emotional investments in other people)-contributed significantly in contrast to Commitment (investments in yourself and your kin). Being psychotic is an excuse for lack of compassion but not having an identified enemy because of paranoid ideation. Furthermore, having pleasurable fantasies about violence is viewed as a sign of poorly developed compassion. Note-worthy is that defence of social status as motive for criminality/violence is viewed as a sign of lack of compassion whereas other motives are irrelevant.

Have we gained a better understanding of Kernberg's [15] term malignant narcissism by these results? Kernberg's [15] view appears to be more relevant (such narcissism has its roots in pathological aggression) than Kohufs [14]: all forms of narcissism are normal. Can we trace the roots of malignant narcissism in the case histories, using the set of variables listed in the EuRAX instrument? None of the expected candidates, like poor childhood, being victimized, the cycle of violence, etc. delivered. It does not appear to be that simple.

Is it meaningful to study evilness empirically? The judicial systems construe the seriousness of crimes and society’s retribution with reference to some kind of hidden evilness concept, and so do lay-men. Over the last 2350 years (since Aristotle wrote the Nicomachean Ethics [28]) such systems have developed a complex set of rules which modulate punishment-excuses. To act without intention, not knowing what one did or that it was wrong to do it, or being unable to act otherwise (free will) is the most common form of excuse, for instance according to the Model Penal Code [29]. Sweden is a strange country - the only one in the world with a Lombroso-inspired judicial system, implemented in 1964/65 and now ready to be replaced because of all problems which have been generated. We created this system because we hailed rationality and feared metaphysics. It back-fired almost immediately.

Capital words, like Evilness, have not been studied much by empirically oriented scientific methods. The SoE appears to work well enough for such studies. We have a unique window of opportunity to study evilness in relation to retribution (labelled value-free as "consequences” if translated from the Swedish term "pafoljd”) in the only metaphysics-free legal system in the world, the current one in Sweden. This window will probably close in the not- too-distant future. Over the years, since its inception in 1964/65, the Swedish courts' practice has drifted with an increasing speed back towards a classic system. In the 1970ies, 75% of all Swedish murderers were sentenced to psychiatric treatment, today it is 15%. In particular it would be interesting to analyse SoE in relation to Mens rea (the subjective criterion of crime) as formulated by Aristotle (350BC) and operationalized in different ways in the world's legal systems, compared to the Swedish concept of "serious mental disorder”, with its politically formulated anti-metaphysical and clinically uninformed definitions, e.g., schizophrenia with only negative symptoms (only!) is not necessarily considered a serious mental disorder in the legal system, neither being Learning disabled, regardless of IQ, even well below 55-such persons are sentenced to prison. In contrast, an Adjustment disorder may constitute a serious mental disorder!

More studies are certainly needed to cross-validate our findings. We think that the time for filling the void between empirical science and the humanities with respect to some key metaphysical concepts like evilness, compassion and conscience is ripe. New insights will be gained, not the least by applying modern techniques to study the working brain. Furthermore, such knowledge can be used in clinical practice. It might be seen as a weakness that a large percentage of our material got score 0 on the SoE, even a number of psychopaths. We think that those with score 0 should be assessed for violence risks with other available instruments like HCR-20. Those scoring >0 should be scrutinized more in depth - in that way it will be possible to identify "unique” dangerousness profiles, which current instruments cannot do, and institute appropriate risk management interventions [30,31].

Conclusion

This is the first study of its kind which confers obvious limitations with respect to generalizability. It is performed in one, strange (with respect to the legal system) but otherwise typically western country, by two assessors assessing 139 patients. In contrast, the Depravity scale studies describe few cases and aims to recruit as many assessors as possible. These two approaches are complementary, not conflicting. By our approach we can study correlates of evilness on the individual level in some depth.

References

- Knoll JL (2008) The recurrence of an illusion: The concept of ’’Evil” in forensic psychiatry. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 36(1): 105-116.

- Welner M (2006) The development of the depravity standard. J Am Acad Psychiatry & Law 34(2): 259-263.

- Welner M (2009) The justice and therapeutic promise of science-based research on criminal evil. J Am Acad Psychiatry & Law 37(4): 442-449.

- Harre R (1970) The principles of scientific thinking. The University of Chicago press, USA.

- Schwartz H (2001) Evil: a historical and theological perspective, Academic Renewal Press, Lima, Ohio, USA.

- Lombroso (1876) L'huomo delinquente. British Library.

- Duntley J, Buss D (2004) The evolution of Evil. In: A Miller (Ed.), The social psychology of good and evil, The Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Webster CD, Eaves D, Douglas KS, Wintrup A (1995) The HCR-20 scheme: The assessment of dangerousness and risk. Vancouver: Simon Fraser University and Forensic Psychiatric Services Commission of British Colombia, Canada.

- Levander S (1979) Psychophysiological differentiation within criminal groups: An approach to the study of psychopathy. MD thesis, the Karo- linska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Hare R (2006) Psychopathy: a clinical and forensic overview. Psychiatr Clin North Am 29(3): 709-724.

- Stone MH (1989) Murder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 12(3): 643-651.

- Stone MH (2009) The anatomy of evil. Prometheus books, USA, ISBN 978-1-59102-726-3.

- Millon T (2000) Sociocultural conceptions of the borderline personality. Psychiatr Clin North Am 23(1): 123-136.

- Kohut H (1972) Thoughts on narcissism and narcissistic rage. The search for the self. International University Press 2: 615-658.

- Narcissism SR (2001) The American contribution-a conversation of raf- faele siniscalcowith otto kernberg. Journal of European Psychoanalysis Winter-Fall 12-13.

- Murphy D (2007) Theory of mind functioning in mentally disordered offenders detained in high security psychiatric care: its relationship to clinical outcome, need and risk. Crim Behav Ment Health 17(5): 300-311.

- Stone MH (2010) Sexual sadism: a portrait of evil. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry 38: 133-157.

- Hare RD, Schalling D (1978) Psychopathy: theory and research. Wiler: NY, USA.

- Hare R (1991) Manual for the hare psychopathy checklist-revised. MultiHealth Systems, Toronto, Canada.

- Cleckley H (1941) The mask of sanity: an attempt to reinterpret the so- called psychopathic personality. St. Louis, USA.

- Schalling D, Lidberg L, Levander S, Dahlin Y (1973) Spontaneous autonomic activity as related to psychopathy. Biological Psychology 1(2): 83-97.

- Hodgins S, Tengstrom A, Eriksson A, Osterman R, Kronstrand R, et al. (2006) A multisite study of community treatment programs for mentally ill offenders with major mental disorders. Criminal Justice and Behaviour 34(2): 211-228.

- Wikström PO (2014) Why crime happens: A situational action theory. In: Manzo G (Ed.), Analytical sociology: actions and networks, Wiley, Sussex, UK, pp. 74-94.

- Silver E (2006) Understanding the relationship between mental disorder and violence: the need for a criminological perspective. Law and Human Behavior 30: 685-706.

- Wikström PO (2006) Individuals, settings and acts of crime. situational mechanisms and the explanation of crime. In Wikström PO, Sampson RJ (Eds.), The explanation of crime: context, mechanisms and development, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Wikström PO (2010) Explaining crime as moral actions. In: Hitlin S, Vaisey S (Eds.), Handbook of the Sociology of Morality. Springer LLC, Germany.

- Wikström PO, Svensson R (2010) When does self-control matter? The interaction between morality and self-control in crime causation. European Journal of Criminology 7: 1-16.

- Aristoteles (0350 BC) Ethika Nicomaceia.

- Model Penal Code and Commentaries (1962) American Law Institute, USA.

- Harris G, Rice M (2015) Progress in violence risk assessment and communication: hypothesis vs evidence. Behav Sci Law 33(1): 128-145.

- Kivisto AJ (2016) Violence risk assessment and management in outpatient clinical practice. J Clin Psychol 72(4): 329-349.

© 2017 Eva Lindstr, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)