- Submissions

Full Text

Experimental Techniques in Urology & Nephrology

Chyluria Presenting as a Non Glomerular Origin of Nephrotic-Range Proteinuria

Emad Abdallah1*, Omar Talal Al Helal2, Bassam Al Helal2, Reem Asad2, Shreeram Kannan3 and Wael Draz2

1 Department of Nephrology, Theodor Bilharz Researrch Institute, Egypt

2 Department of Nephrology, Al-Adan hospital, Kuwait

3 Radiology center, Al-Adan hospital, Kuwait

*Corresponding author: Emad Abdallah, Department of Nephrology, Theodor Bilharz Researrch Institute, Cairo, Egypt

Submission: February 22, 2018;Published: August 20, 2018

ISSN 2578-0395Volume2 Issue3

Abstract:

Background: Chyluria (excretion of chyle from the urinary tract) is a rare condition that can be mistaken for nephrotic syndrome because of its presentation with heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and edema. We report a case of chyluria presented with milky urine and nephrotic-range proteinuia.

Case presentation: A 36-year-old Bangladesh woman gave a history of episodic cloudy urine for the last 2 years (2014 after 2nd pregnancy). history of 3 month abortion 2015. During her last pregnancy (2014), she was noted to have proteinuria (5g/24 h). Physical examination was normal. Renal function test was normal, absolute esinophilia. Urine analysis revealed milky urine, protein 5g/l, no cast, no dysmorphic RBCS, urine cholesterol 0.52mmol/l (n 0-0.26), urine triglycerides 7.04mmol/l (n 0-0.1). A 24-h urine collection was 6.8g of protein. Anti nuclear antibody, anti DS DNA and ANCA were -ve. Complement C3 and C4 were normal. Hepatitis C antibody and hepatitis B surface antigen were -ve. An abdominal ultrasound showed the kidneys were normal in size, position and echotexture. Differential diagnosis of the nephrotic-range proteinuria was membranous nephropathy or minimal change disease or chyluria. Kidney biopsy findings of intact foot processes and absence of glomerular histologic abnormalities are helpful to exclude intrinsic renal disease and should prompt an appropriate work-up for chyluria.

Conclusion: Chyluria should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the patient who presents with cloudy or milky urine.

Keywords: Chyluria; Milky urine; Proteinuria

Introduction

Chyluria is the excretion of chyle from the urinary tract [1-3]. Chyle is defined as the lymphatic fluid in the intestinal lacteals that contains absorbed fat in the form of chylomicrons. The presence of chylomicrons in a stable emulsion gives this intestinal lymph a milky appearance [2]. Chyluria indicates the presence of an abnormal communication between intestinal lymphatics and the urinary tract. This communication is caused by the obstruction of lymphatic drainage proximal to intestinal lacteals, resulting in variceal dilatation of distal lymphatics and eventual rupture of lymphatic vessels into the urinary tract, creating a lymphatic urinary fistula [1-5]. The location of lymphatic urinary fistula is most commonly at the calyceal fornix in the renal pelvis, but can also occur at the level of the ureter or urinary bladder [2-5].

Case Presentation

A 36-year-old Bangladesh women, married and have 2 children. She gave a history of episodic cloudy urine for the last 2 years (2014 after 2nd pregnancy). History of 3 month abortion 2015. During her last pregnancy (2014), she was noted to have proteinuria (5g/24h). There was no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, renal stones, or gross hematuria. Physical examination revealed a well developed woman weighing 65.5kg with a temperature of 37 °C, pulse 86/min, and blood pressure100/60mmHg. She was conscious, alert, oriented, no pallor, no jaundice, no cyanosis. Normal jugular venous pressure. There was no lymphadenopathy. There was no skin rash. The heart and lung examinations were normal. The abdomen was soft with no organomegaly. There was no lower limb edema.

Renal function test

Serum creatinine 60umol/L, urea 4.4mmol/L, NA 140mmol/L, K 4.6mmol/L. Complete blood count: Total leucocyte count 7.9 × 109/l, haemoglobin 13, platelet 422× 109/l, absolute esinophilia 0.66, esinophils 8.3.

Lipid profile

Total cholesterol 6.38mmol/L, LDL 1.67mmol/L, HDL 1.2mmol/L, triglycerides 1.42.mmol/L.

Serum glucose

5.6mmol/L. Liver function.

Test

Total bilirubin 4umol/L, alanine aminotransferase 26U/L, alkaline phosphatase 97 U/L, s. albumin 40mmol/L, PT 11, PTT 30.5, INR 0.9.

Serum electrolytes

Total CA 2.2mmol/L, po4 1.1mmol/L, choloride 109mmol/L, Mg 0.8 mmol/L. Urine analysis revealed milky urine, protein 5g/l, -ve leukocyte esterase, WBC 0-2/HPF, RBCS 10-15/HPF, no cast, no dysmorphic RBCS, no acid fast bacili in urine, urine cholesterol 0.52mmol/l (n 0-0.26), urine TGs 7.04mmol/l(n 0-0.1). A 24-h urine collection was 6.8g of protein. Antinuclear antibody, anti DS DNA and ANCA were -ve. The serum complement levels including C3, C4, were normal. Hepatitis C antibody and hepatitis B surface antigen were –ve. Examination of stained urine sediment by modified Wright stain (Hansel’s stain) revealed many isomorphic RBCs and lymphocytes. Addition of Sudan III to an aliquot of this milky urine, followed by mixing and shaking with an equal volume of chloroform and centrifugation, produced clearing of the cloudy urine with the appearance of stained fatty globules in the organic layer (Figure 1). A urine protein electrophoresis showed non-selective proteinuria. A chest X-ray and an ECG were normal. An abdominal ultrasound showed the kidneys were normal in size, position and echotexture. Differential diagnosis of the renal abnormalities included nephrotic syndrome owing to membranous nephropathy or minimal change disease or chyluria.

Kidney biopsy was performed

Two cores of tissue were received measuring 1.6 and 1.5cm. Sections of kidney cortex show 37 glomeruli. All glomeruli appear normal. No sgnificant interstitial fibrosis is seen. No arterial pathology is present. Immunoperoxidase staining for IgA, IgG, IgM and C3 were -ve in glomeruli. In short, the kidney biopsy showed no evidence of immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis. The absence of foot process effacement ruled out minimal change disease. By exclusion, the normal kidney biopsy findings supported proteinuria on a non-glomerular basis, as might occur secondary to chyluria. Before work-up for chyluria and filariasis could be initiated, the patient returned to the Bangladesh and was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

The etiology of chyluria can be classified as either parasitic or non-parasitic [2-5]. Lymphatic filariasis is the most common cause of parasitic chyluria in persons living in endemic areas, including India, China, Southern Japan, Southeast Asia, the South Pacific islands, tropical sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean islands, including Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and the northeast coast of South America [3-6]. Wuchereria bancrofti infection accounts for most of the lymphatic filariasis worldwide [3-6]. Chyluria is a late and uncommon manifestation of chronic lymphatic filariasis [2,3]. In one epidemiologic study, chyluria was present in 0.7% of the population in an endemic area, and in another clinical study, chyluria was diagnosed in 2% of urologic patients with filarial infection [7,8].

Diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis is usually made by the detection of microfilaria on thick Giemsa-stained blood smears, which requires late night examination (around midnight) because of the nocturnal periodicity of the circulating parasites. In recent years, circulating filarial antigen detection tests have been introduced, including the commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay antigen test using monoclonal antibodies and the immunochromatography filarial antigen test using polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies. The filarial antigen tests are more sensitive than thick smear or membrane filtration for the detection of W. bancrofti and can be performed on samples collected during the day. Detection of filarial DNA by polymerase chain reaction is also available in some centres.

The non-parasitic causes of chyluria are rare and include granulomatous disease (such as tuberculosis, fungal infection, and leprosy), congenital anomalies of lymphatic system (such as lymphangioma), malignancy, trauma, venous stasis, pregnancy, aortic aneurysm, and lymphatic obstruction after surgery or cardiac catheterization [2,5,9,10]. A past history of residing in the tropical or subtropical endemic area for lymphatic filariasis will suggest a possible parasitic etiology of chyluria, whereas a history of invading malignancy or tuberculosis will suggest obstruction of lymphatic drainage by malignant cells or mycobacterial infection. The presence of unilateral lymphedema may occur in patients with congenital anomalies of the lymphatic system.

Patients with chyluria typically describe the passage of milky white urine. However, some patients may be entirely asymptomatic, whereas others may complain of renal colic with passage of clots. Gross inspection of a freshly voided urine specimen typically shows milky and cloudy urine, which remains turbid after centrifugation. On standing, the urine may separate into three layers: a top layer of chylomicrons, a middle layer containing protein, and a bottom layer of fibrin clots and cellular elements.2A dipstick test for urine chemistry usually shows heavy protein and moderate blood, but leukocyte esterase (an enzyme present in granulocytes, but not lymphocytes) is usually negative, unless there is a complicating urinary tract infection. Because the lymphatic fluid contains albumin, as well as higher molecular weight globulins and fibrinogen, with a total protein concentration in the range of 3-6 g/ dl [11], a 24h urine collection in patients with chyluria often reveals nephrotic-range proteinuria that appears ‘non-selective’ on urine protein electrophoresis.

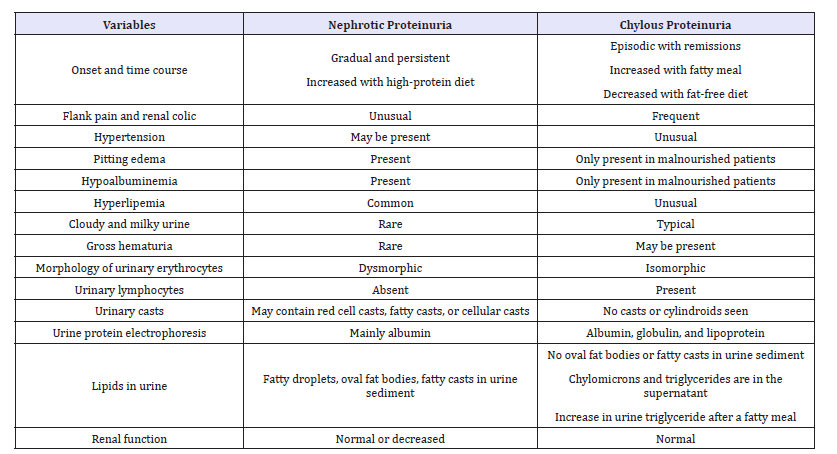

Despite the presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria, microscopic examination of the urinary sediment does not reveal the lipid-laden oval fat bodies or fatty casts typically seen in patients with nephrotic syndrome [1,12]. This is because the proteinuria is not originating from glomeruli or renal tubules, but is ‘post-nephron’ in origin. Instead, one may see large numbers of lymphocytes (not neutrophils) in the urine sediment, consistent with the leakage of lymphatic fluid into the urine [1,2,5,11]. In chyluric patients with hematuria, which is caused by the rupture of blood vessels into the urinary tract during the formation of lymphaticourinary fistula, the red cells in the urine sediment are typically isomorphic, and no red blood cell casts or white blood cell casts are observed. The presence of dysmorphic red cells in the urinary sediment associated with significant proteinuria, oval fat bodies, granular casts, or cellular casts in a patient with chyluria should raise the suspicion of a coexistent glomerular disease [13]. (Table 1) compares the clinical features of nephrotic proteinuria and chylous proteinuria.

Table 1:Comparison of nephrotic proteinuria and chylous proteinuria.

The presence of chyle in the urine can be confirmed by shaking an aliquot of turbid urine with equal volume of chloroform or ether, which extracts the triglyceride-rich fatty emulsion into the organic layer, leaving the remaining urine clear (Figure 1). The diagnosis of chyluria can also be confirmed by demonstrating a timed increase in the excretion of urinary triglyceride approximately 4 h after a fatty meal [14]. The presence of lymphocytes in the urinary sediment is also consistent with the presence of chyle in the urine [1,2,5]. The differential diagnoses of turbid urine should also include pyuria owing to urinary tract infection and crystalluria resulting from precipitation of phosphate in an alkaline urine. The former can be diagnosed by the presence of many neutrophils, rather than lymphocytes, in the urinary sediment and the latter can be diagnosed by acidification of the urine with acetic acid, which dissolves the precipitated phosphate [15]. Further evaluation of chyluria includes localization of the side, the site, and the level of lymphatic urinary fistula, and the assessment of the underlying etiology. This is best achieved by performing cystoscopy after a fatty meal, allowing the identification of the ureteral orifice that is passing milky urine or a site of chylous efflux into the bladder or urethra [2,8]. This is followed by lymphangiography for the detection of the level and site of lymphatic urinary fistula formation. Although lymphangiography is the procedure of choice for localization of lymphatic urinary shunt, it requires cannulation of small lymphatic vessels in the foot and injection of lipid contrast medium (Ethiodol) into the lymphatic system, followed by serial pelvic and abdominal radiography for visualization of lymphatics and lymph nodes in the pelvic, retroperitoneal, and para-aortic regions [4,16]. In patients with chyluria, lymphangiography typically shows marked dilatation and tortuosity of the lymphatics around the hilar regions of the kidneys, followed by opacification of the calyceal systems [4,16].

In a minority of patients, the lymphaticourinary communication may be seen at the level of ureter or urinary bladder. It should be noted that the procedure of lymphangiography is technically challenging, requiring a skilled operator, and is not without complications. A non-invasive and equally accurate lymphoscintigraphy has been increasingly utilized for the evaluation of chyluria; it allows the clear and precise analysis of the lymphatic system function in patients with filarial infection [3]. Because spontaneous remission of chyluria may occur in 50% of patients [17], patients may not require treatment if the chyluria enters a long interval of remission without nutritional complications. However, in patients with persistent chyluria and malnutrition from excessive urinary losses of lipids and protein, a specifically designed low-fat, high-protein diet and medium-chain triglycerides has been demonstrated to decrease the proteinuria, lipiduria, and hematuria [18].

In some patients, diagnostic contrast lymphangiography may prove to be therapeutic by causing serendipitous closure of the lymphatic urinary fistula owing to its sclerosing effect on the lymphatic vessels [4]. For patients with recurrent or persistent chyluria unresponsive to medical management, instillation of sclerosing solutions (such as silver nitrate) into the renal pelvis has 80% success rate in achieving closure of the lymphaticopelvic communication [19]. For those patients who fail the renal pelvic instillation sclerotherapy, surgical or retroperitoneoscopic renal pedicle lymphatic disconnection is the treatment of choice [20].

Conclusion

Chyluria is a rare condition that can be mistaken for nephrotic syndrome because of its presentation with heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and edema in malnourished individuals. The renal biopsy findings of intact foot processes and absence of glomerular histologic abnormalities are helpful to exclude intrinsic renal disease and should prompt an appropriate work-up for chyluria. Chyluria should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the patient who presents with cloudy or milky urine.

References

- Yamauchi S (1945) Chyluria: clinical, laboratory and statistical study of 45 personal cases observed in Hawaii. The Journal of Urology 54(3): 318-347.

- Diamond E, Schapira HE (1985) Chyluria --a review of the literature. Urology 26(5): 427-431.

- (1992) Lymphatic filariasis: the disease and its control. Fifth report of the WHO expert committee on Filariasis. Send to World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 821: 1-71.

- Akisada M, Tani S (1968) Filarial chyluria in Japan. Lymphography, etiology and treatment in 30 cases. Radiology 90(2): 311-317.

- Koo CG, Van Langenberg A (1969) Chyluria. A clinical study. J R Coll Surg Edinb 14(1): 31-41.

- Buck AA, Filariasis (2002) In: Strickland GT (Ed.), Hunters Tropical Medicine, (7th edn), WB Saunders: Philadelphia, USA, pp. 713-727

- Fan PC (1990) Filariasis eradication on Kinmen Proper, Kinmen (Quemoy) Islands, Republic of China. Acta Trop 47(3): 161-169.

- Ray PN, Rao SS (1939) Chyluria of filarial origin. B JUI BJU Intrnational 11: 48-64.

- Garrido P, Arcas R, Bobadilla JF, Albertos J, González Santos JM et al. (1995) Thoracic aneurysm as a cause of chyluria: resolution by surgical treatment. Ann Thorac Surg 60(3): 687-689.

- Chen HS, Yen TS, Lu YS, Yang JC, Ko YL (1996) Transient ‘milky urine’ after cardiac catheterization: another unreported cause of non-parasitic chyluria. Nephron 72(2): 367-368.

- Drinker CK, Field ME, Heim W, Octa c Leigh JR (1934) The composition of edema fluid and lymph in edema and elephantiasis resulting from lymphatic obstruction. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 109(3): 572-586.

- Zimmer JG, Dewey R, Waterhouse C, Terry R (1961) The origin and nature of anisotropic urinary lipids in the nephrotic syndrome. Ann Intern Med 54: 205-214.

- Lai KN, Siu D, Chan KW Lai FM, Yan KW (1986) The clinical significance of proteinuria in patients with nonparasitic chyluria. Am J Kidney Dis 7(5): 381-385.

- Peng HW, Chou CF, Shiao MS, Lin E, Zheng HJ, et al. (1997) Urine lipids in patients with a history of filariasis. Urol Res 25(3): 217-221.

- Henry JB, Lauzon RB, Schumann GB (1996) Basic examination of urine. In: Henry JB (Eds.), Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. WB Saunders: Philadelphia, USA, pp. 411-456.

- Kittredge RD, Hashim S, Roholt HB, Van Itallie TB, Finby N (1963) Demonstration of lymphatic abnormalities in a patient with chyluria. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 90: 159-165.

- Ohyama C, Saita H, Miyasato N (1979) Spontaneous remission of chyluria. J Urol 121(3): 316-317.

- Hashim S, Roholt HB, Babyyan VK, Van Itallie TB (1964) Treatment of chyluria and chylothorax with medium-chain triglyceride. N Engl J Med 270: 756-761.

- Dalela D, Rastogi M, Goel A, Gupta VP, Shankhwar SN (2004) Silver nitrate sclerotherapy for ‘clinically significant’ chyluria: a prospective evaluation of duration of therapy. Urol Int 72(4): 335-340.

- Zhang X, Zhu QG, Ma X, Zheng T, Li HZ, et al. (2005) Renal pedicle lymphatic disconnection for chyluria via retroperitoneoscopy and open surgery: report of 53 cases with follow up. J Urol 174(5): 1828-1831.

© 2018 Emad Abdallah. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)