- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Open Access

Rehabilitative And Pharmacological Treatment for Posterior-Variant Alien Hand Syndrome: A Case Report

Michael Appeadu*, Jennifer Gomez, Adriana Valbuena Valecillos and Gemayaret Alvarez

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation PGY-4, University of Miami, US

*Corresponding author: Michael Appeadu, MD, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation PGY-4, University of Miami, Jackson Memorial Hospital, USA

Submission: May 16, 2022; Published: June 16, 2022

ISSN 2637-7934 Volume3 Issue4

Abstract

previously independent 54-year-old ambidextrous male presented to the hospital with frequent syncopal episodes and chest pain and was diagnosed with subclavian steal syndrome. After undergoing subclavian stent placement, he was found to have left hemineglect, and imaging revealed a right parietal infarction. After subsequently displaying involuntary arm movements including levitation and fist clenching, the patient was diagnosed with the rare posterior variant of Alien Hand Syndrome upon admission to inpatient rehabilitation. Based on anecdotal efficacy described in a few case reports, clonazepam was started alongside therapy techniques, including compensatory distraction methods, mirror therapy, verbal cueing, and visual feedback. The patient demonstrated improvement over the course of his 16 days stay in inpatient rehabilitation, as evidenced by patient-reporting, an increase in functional independence measure from 49/126 to 80/126, and an improvement by 15 points on the Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) for the left hand. This case report aims to use available literature to highlight an uncommon debilitating condition, detail diagnostic and assessment tools, and discuss treatment options

Introduction

Alien hand syndrome (AHS) is a rare condition in which patients present with involuntary limb movements and a feeling of loss of limb ownership. It was first detailed in 1908 in a case in which a patient suffered a stroke and thereafter reported her left hand had a “will of its own” and grabbed her throat. Several reports subsequently emerged over the next century, including two patients described in 1990 who displayed impulsive right hand groping behavior against their will. It was at this time the term “alien hand” was coined. The causes of alien hand syndrome are varied, and include but are not limited to: Stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, and neurosurgical operations. The pathophysiology has not been completely elucidated, but the most common theories support neural network disinhibition or disconnection syndromes [1].

AHS is usually divided into three variants based on lesion location in the brain: Frontal, callosal, and posterior, with posterior being the rarest [2]. Each variant has characteristic features, but patients may display features of multiple. The frontal variant usually results from an affected supplementary motor area, cingulate gyrus or corpus callosum. It presents with groping, grasping, or utilization behavior. The callosal variant, named for a lesion in the corpus callosum, will characteristically present with intermanual conflict. The posterior variant’s commonly affected areas include the parieto-occipital cortices and the thalamus. The posterior variant will present with levitation and abnormal posturing of the limb, as well as cortical sensory deficits [3]. In stroke patients it has been proposed that AHS be defined according to the brain hemisphere involved, rather than the above-described variants [4]. Still, the division into variants is the most commonly used categorization.

There are currently no approved standardized treatments for alien hand syndrome; Management is based on anecdotal interventions [3]. Addressing etiologic factors is generally accepted as the only effective treatment. Rehabilitation therapies, including cognitive behavioral therapy, visual space training, and distraction have improved symptoms [5]. Mirror therapy has also been demonstrated to lead to motor improvement [6]. An individualized rehabilitation program tailored to the patient’s requirements is an important consideration [7]. Pharmacologic treatment methods for alien hand syndrome are variable and include: Maintenance of platelet aggregation inhibitors or anticoagulants to prevent further stroke [8], clonazepam, [2,9-12] botulinum toxin A injection, [9] an immunosuppressant in a case of AHS caused by a form of autoimmune vasculitis, [13] carbamazepine after using clonazepam in a case with associated dystonia and painful spasms, [12] and intravenous diazepam for a case of AHS which presented possibly as a result of seizures [14]. As evidenced in a case of alien hand syndrome treated with both therapeutic and pharmaceutical measures, the combination of the two interventions improved patient quality of life when evaluated by clinical observation, functional independence measures, and patient-reporting [10].

Case Report

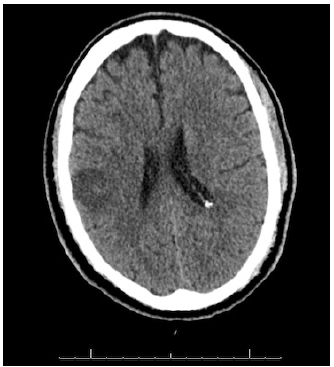

We present the case of a previously independent 54-year-old ambidextrous male with an extensive cardiovascular past medical history of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, vertebral occlusions, bilateral subclavian artery stenosis, percutaneous coronary intervention, and carotid stenosis who initially presented to the hospital with chest pain with strenuous activities, and fainting spells during laughing or coughing. The patient reported four syncopal episodes in the past year, the last occurring 5 months prior to presentation. He was diagnosed with subclavian steal syndrome and underwent right subclavian and right innominate artery stents. Post-extubation, the patient was found to have left hemineglect and a stroke alert was called. CT of his brain was notable for hypodensities in the right frontoparietal and left parietal region suggestive of stroke (Figure 1). CTA redemonstrated extensive intracranial and extracranial atherosclerotic changes. No tPA was administered as the patient was outside the therapeutic window. The patient was stabilized, continued on aspirin and Ticagrelor, and admitted to our inpatient rehabilitation center to maximize function and independence with physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy 3 times per day, 6 days per week over the course of 16 days.

Figure 1:CT Brain.

At the point of admission to inpatient rehabilitation, the patient complained of “electrical pain” in his left arm, weakness, involuntary left arm movements such as reaching behind his head and raising his arm up in the air, and insomnia. At times, the patient’s left arm became clenched uncontrollably. He became frustrated and stated, “it has a mind of its own.” On examination he was oriented to self and time, but not location. He displayed severe left sided inattention, impaired bilateral upper and lower extremity coordination, decreased left upper and lower extremity proprioception, and left upper extremity ataxia. Muscle strength testing was 4/5 in his left upper and lower extremity, and 5/5 in all other extremities. He was found to have increased tone in his left triceps, with a modified Ashworth scale score of 1+/4. Reflexes were 1+ throughout, and he was found to have no clonus and negative Hoffman’s sign. The patient demonstrated motor apraxia and decreased functional mobility to complete activities of daily living. Given the patient’s clinical findings, he was diagnosed with posterior variant AHS.

After reviewing the limited literature on AHS on Pubmed using the search terms “Alien Hand Syndrome treatment” or “Alien Hand syndrome treated,” we found 28 relevant case reports in which patients with alien hand syndrome were treated with rehabilitation, medication, or both. The available literature is applicable to our case. For the first week of inpatient rehabilitation, the patient was treated by physical therapists, occupational therapists, neuropsychologists and speech therapists with various rehabilitation techniques, including verbal and tactile cueing, constraint therapy, mirror therapy, biofeedback, and distraction of the affected limb. After a week, the left hand symptoms had only minimally improved. We started the patient on Clonazepam 0.5mg at bedtime, with the plan to increase to twice daily if he tolerated the initial dose. Given the patient’s insomnia, the clonazepam was intended to both aid the patient with sleep and his AHS. That night, however, the patient became more restless, so the nightly dose of clonazepam was discontinued. The patient was subsequently given Quetiapine 12.5mg at night for insomnia as he had already failed melatonin and trazodone, and did not improve with sleep hygiene strategies by that time. For AHS he was started on Clonazepam 0.25mg in the morning until discharge. His left hand symptoms improved over this time period.

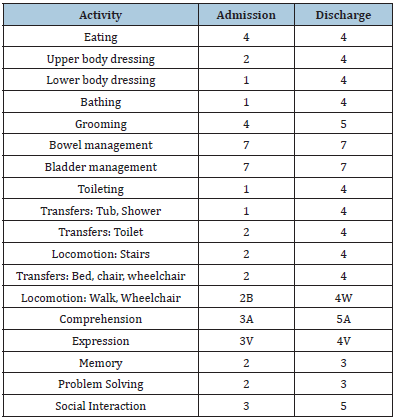

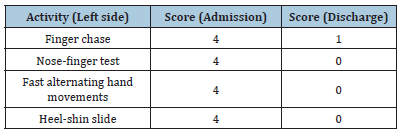

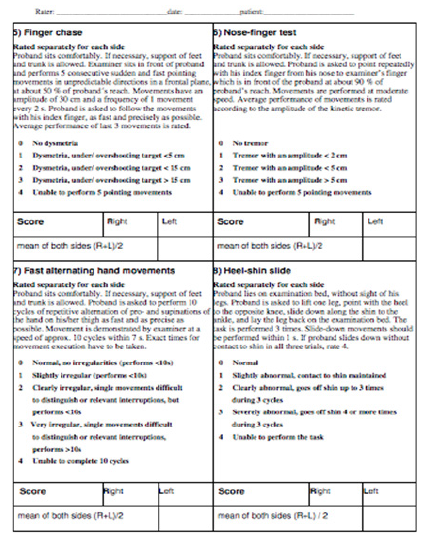

The patient’s AHS was assessed using the functional independence measure (FIM) and the Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA). On admission, the patient’s FIM score was 49/126. On discharge, FIM was 80/126 (Table 1). On admission, the Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) initial score for the patient’s left hemibody was 16/16, and on discharge the score was 1/16 (Table 2). At the time of discharge, the patient reported no pain, and demonstrated improvement in the functional use of his left upper extremity for ADLs. He and his family were educated on his deficits, and techniques to counteract them to support his safety during mobility and ADLs. The patient was advised to follow-up for outpatient physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and neuropsychology.

Table 1:FIM scores.

Table 2:Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia (SARA).

Discussion

Based on our patient’s clinical findings after his stroke, we were able to diagnose a specific variant of alien hand syndrome which would guide treatment options. The lesion location fits the typical non-dominant (right) parietal lobe location which tends to occur with the posterior variant of AHS. The posterior variant of AHS commonly affects the left, non-dominant hand and leads to involuntary motor activity in the affected extremity that is characteristically less complex (levitation of the limb, ataxia, and clumsy, non-purposeful movements). Our patient’s hemineglect and description of the limb feeling as though it is not his own, or “foreignness,” is not a universal finding in AHS, and is experienced most commonly with the posterior variant [1]. In making the diagnosis of alien hand syndrome it is important to rule out extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and seizures. Given that our patient had parietal lobe infarctions, non-rhythmic and paroxysmal movements, and no antipsychotic medication use, EPS was unlikely. Seizures were also ruled out considering that the patient maintained a conscious state during the involuntary limb movements and the movements did not subscribe to a tonic or clonic nature [2].

Rehabilitation strategies for AHS were employed based on both the available literature and his specific clinical presentation. Compensatory strategies including distraction of the affected limb have been shown to reduce the frequency of AHS movements and were therefore employed early on in the patient’s rehabilitation course [15]. In one AHS case study, mirror therapy was shown to improve patient motor speed by restoring concordance between visual feedback and motor intentions. Our occupational therapists utilized this technique in our patient in an attempt to improve voluntary motor control [6]. The patient’s AHS manifested with random, involuntary hand-clenching, which caused difficulty in completing a familiar game of dominoes. He also frequently dropped pieces when attempting to complete the nine-hole-PEG test. This was addressed with verbal cueing and tactile cueing; however, the patient’s hemianopsia compounded his AHS motor deficits. Moving his left hand into the right hemispace to increase visual feedback, a known method to be efficacious, was implemented with demonstrated improvement [16].

After one week of inpatient rehabilitation, the patient’s AHS had not resolved. Most studies detailing pharmacological treatment of AHS after cerebrovascular accidents report the usage of only preventative antiplatelet therapy, usually in combination with rehabilitation [4]. This supportive method has not always yielded significant improvement [17]. Our patient was placed on clonazepam initially to target both AHS and insomnia. He unfortunately did not tolerate the bedtime dose, so a lower dose in the morning was given instead. The benzodiazepine has demonstrated efficacy in a few studies for AHS, purportedly due to its effect on GABA receptors, which has been effective in treating dystonia [9]. Botulinum toxin A was also considered as treatment. The mechanism of effect of botulinum toxin A may be related with a sensory effect, a small decrease in strength or both. In one study, a patient with AHS had greater response to botulinum toxin A than clonazepam, but it is still difficult to make generalizations regarding efficacy from a single case [9]. Given the quicker onset of drug action, a limited ability for outpatient therapy given the COVID-19 pandemic, and patient financial considerations, clonazepam was the preferred treatment.

It is important to address patient emotional issues as well when treating AHS. Initially, our patient displayed stress and frustration with the rehabilitation process. Patient stress and emotions may worsen symptoms of AHS. 4 It was therefore crucial that the neuropsychology team assess the patient. He was receptive to these sessions to process his emotions, and became considerably less irritable over his rehabilitation course. Mood symptoms can be exacerbated by decreased sleep. Therefore, addressing the patient’s insomnia with low dose quetiapine after other sleep agents did not help was an important factor in his recovery. Although it is unknown if it was directly tied to AHS, insomnia is a common occurrence in stroke patients and should be addressed during the rehabilitation of this patient population [18].

Figure 2:Supplementary material: SARA scale items 5-8.

Our patient’s posterior variant of AHS has a good prognosis [19]. In addition, right hemispheric lesions in stroke carry a better prognosis than left hemispheric [4]. When AHS is secondary to infarction, symptoms usually cease in 6-12 months [9]. With the combination of treatment measures for our patient, he made significant improvement over the course of a 16 day rehabilitation stay. He demonstrated improved functional use of his left upper extremity for ADLs, as evidenced by the improvement in FIM score (Table 1) We utilized the SARA scale (Figure 2), a potentially valuable clinical assessment tool for ataxia, as a rehabilitation index for independence in our patient’s left hand ADL performance. Our patient’s AHS was scored using the motor activity categories (items 5-8) [20]. Usually, the assessments are performed bilaterally with the mean of the values recorded, but for our purposes, only the left hemibody values were evaluated given our focus on the patient’s known deficits.

Conclusion

As evidenced by our patient’s improvement in his symptoms, our case provides a window into the role of a combination of rehabilitation and clonazepam in the treatment of posteriorvariant AHS. More sensitive outcome measures are still needed for the assessment of this condition [15]. With increased awareness about AHS, clinical practitioners will hopefully be able to make accurate diagnoses and appropriate interventions to improve patient function, and in turn quality of life.

References

- Hassan A, Josephs KA (2016) Alien Hand Syndrome. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 16(8): 73.

- Demiryurek BE, Gundogdu AA, Acar BA, Alagoz AN (2016) Paroxysmal posterior variant alien hand syndrome associated with parietal lobe infarction: case presentation. Cogn Neurodyn 10(5): 453-455.

- Sarva H, Deik A, Severt WL (2014) Pathophysiology and treatment of alien hand syndrome. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 4: 241.

- Kikkert MA, Ribbers GM, Koudstaal PJ (2006) Alien hand syndrome in stroke: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 87(5): 728-732.

- Shao J, Bai R, Duan G, Guan Y, Cui L, et al. (2019) Intermittent alien hand syndrome caused by Marchiafava-Bignami disease: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(34): e16891.

- Romano D, Sedda A, Dell'aquila R, Dalla CD, Beretta G, et al. (2014) Controlling the alien hand through the mirror box. A single case study of alien hand syndrome. Neurocase 20(3): 307-316.

- Pappalardo A, Ciancio MR, Reggio E, Patti F (2004) Posterior alien hand syndrome: case report and rehabilitative treatment. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 18(3): 176-181.

- Nowak DA, Bosl K, Ludemann PJ, Gdynia HJ, Ponfick M (2014) Recovery and outcome of frontal alien hand syndrome after anterior cerebral artery stroke. J Neurol Sci 338(1-2): 203-206.

- Haq IU, Malaty IA, Okun MS, Jacobson CE, Fernandez HH, et al. (2010) Clonazepam and botulinum toxin for the treatment of alien limb phenomenon. Neurologist 16(2): 106-108.

- Alvarez A, Weaver M, Alvarez G (2020) Rehabilitation of Alien Hand Syndrome Complicated by Contralateral Limb Apraxia: A Case Report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 99(10): e122-e124.

- Qureshi IA, Korya D, Kassar D, Moussavi M (2016) Case Report: 84 year-old woman with alien hand syndrome. F1000Res 5: 1564.

- Sabrie M, Berhoune N, Nighoghossian N (2015) Alien hand syndrome and paroxystic dystonia after right posterior cerebral artery territory infarction. Neurol Sci 36(9): 1709-1710.

- Chokar G, Cerase A, Gough A, Sibte H, David S, et al. (2014) A case of Parry-Romberg syndrome and alien hand. J Neurol Sci 341(1-2): 153-157.

- Feinberg TE, Roane DM, Cohen J (1998) Partial status epilepticus associated with asomatognosia and alien hand-like behaviors [corrected]. Arch Neurol 55(12): 1574-1576.

- Pooyania S, Mohr S, Gray S (2011) Alien hand syndrome: a case report and description to rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 33(17-18): 1715-1718.

- Groom KN, Ng WK, Kevorkian CG, Levy JK (1999) Ego-syntonic alien hand syndrome after right posterior cerebral artery stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 80(2): 162-165.

- Mahawish K (2016) Corpus callosum infarction presenting with anarchic hand syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2016: bcr2016216071.

- Leppavuori A, Pohjasvaara T, Vataja R, Kaste M, Erkinjuntti T (2002) Insomnia in ischemic stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis 14(2): 90-97.

- Pack BC, Stewart KJ, Diamond PT, Gale SD (2002) Posterior-variant alien hand syndrome: clinical features and response to rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 24(15): 817-818.

- Kim BR, Lim JH, Lee SA, Seunglee P, Seong EK, et al. (2011) Usefulness of the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) in Ataxic Stroke Patients. Ann Rehabil Med 35(6): 772-780.

© 2022 Michael Appeadu. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)