- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Open Access

Essential Actions when Developmental Coordination Disorder is Suspected

Lisa Dannemiller*

University of Colorado Physical Therapy Program, USA

*Corresponding author: Lisa Dannemiller, University of Colorado Physical Therapy Program, USA

Submission: August 02, 2021; Published: August 17, 2021

ISSN 2637-7934 Volume3 Issue3

Abstract

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a common childhood condition, impacting 5-6% of school-aged children. A high percentage of physicians are not familiar with DCD, which is outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). A physical therapist’s experience with both the literature and the clinical presentation of DCD is offered to guide physiatrists with 6 essential actions in the collaborative efforts necessary for the management of individuals with DCD.

Keywords: Pediatricians; Physiatrist; Motor coordination; Diagnostic

Introduction

Developmental coordination disorder is a condition described in the DSM-5 with

a prevalence of 5-6% of school-aged children, yet it is a largely underrecognized in the

medical community [1,2]. Only 23-41% of physicians (general physicians and pediatricians,

respectively) are familiar with DCD and most express a need for more information about this

diagnosis[3]. Parents report taking an average of 2.5 years from the time concerns about their

child are identified to diagnosis[4]. Raising awareness about DCD and educating colleagues

can contribute to more consistency in examination and intervention for children suspected of

DCD and their families [5].

The process of diagnosing DCD requires a collaborative effort among professionals

because it is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion with no imaging study, laboratory or genetic

test that currently confirms a DCD diagnosis. Physicians and physical therapists (PTs) need

to work together to confirm all 4 of the following DSM-5 criteria as a diagnosis of DCD is

considered.

a) Criteria A: Acquisition and execution of coordinated motor skills are substantially

below what is expected based on the child’s age

b) Criteria B: Evidence that the child’s motor deficits persistently and significantly

interfere with activities of daily living and participation in play, school and prevocational

activities

c) Criteria C: Onset of symptoms is in the developmental period, typically before the

age of 5

d) Criteria D: No other neurological or medical condition accounts for motor skills

deficits.

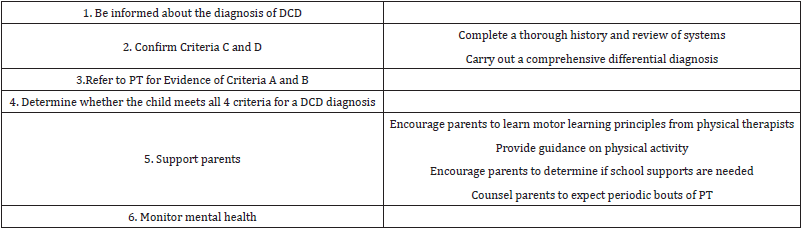

Six essential activities are recommended for physiatrists when a diagnosis of DCD is

suspected. (see Table 1)

Table 1: Essential actions when developmental coordination disorder is suspected.

Be informed about the diagnosis of DCD

The international DCD clinical practice recommendations for all professionals are a comprehensive consensus document with valuable clinical information[6]. A physical therapy clinical practice guideline allows physiatrists to gain an understanding of recommendations and collaborations with PTs [7]. A number of systematic reviews and research articles may also be reviewed to address specific questions related to DCD.

Confirm Criteria C and D

The physiatrist’s thorough history and review of systems will determine whether the child’s motor coordination deficits were noticed by parents or medical professionals at a young age. The history and review of systems will also lead the physiatrist through a comprehensive differential diagnosis, which may include imaging, genetic testing, laboratory tests, and neurological examination. Physiatrists should be aware that DCD co-occurs with many other conditions, most frequently, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder [8]. If there are no significant findings that lead to a diagnosis that explains the child’s motor coordination deficits, then consider referral to a PT.

Refer to PT for evidence of Criteria A and B

Physical therapists (or occupational therapists) are partners in the process of identifying a child’s motor performance deficits. This will include the use of a standardized motor test, most often the Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2nd edition to confirm Criteria A [9]. Children who score less than the 5th percentile have significant movement difficulty and probable DCD. Those in the 5th to 15th percentile have movement difficulty and are described as being at risk for DCD [10]. Physical therapists will also complete questionnaires with families or school personnel to document limitations in participation in the home, school or community, including the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire 2007 [11] or other participation measures.

Determine whether the child meets all 4 criteria for aDCD diagnosis

Gathering information from the history, review of systems, differential diagnosis, along with test result about motor performance and participation from the PT, will allow the physiatrist to consider whether all DSM-5 criteria are met for a diagnosis of DCD.

Support parents

There are many parent support activities that may ultimately influence the concerns of parents and the outcomes of children with DCD. Physiatrists can assure parents that PTs can teach parents about motor learning principles to use when motor challenges arise. Physiatrists or PTs can share with families that a decrease in physical activity, common in children with DCD, may result in cardiovascular disease and obesity [12,13]. Encouraging children to participate in sports or recreation activities of interest to them is highly recommended. Children with DCD may have anxiety or emotional challenges if their performance is poorer than peers in a group team sports (i.e., baseball, soccer, basketball). Parents may guide their child to individual sports/activities or individual team sports (i.e., swimming, climbing, running) to foster confidence in physical skills [6,14] A child’s success at school may be a valuable consideration for the physiatrist as special education services or accommodations may be options for the parent to pursue. Physiatrist should let parents know that their child may have periodic bouts of physical therapy throughout their childhood and that motor difficulties may even persist into adulthood [2].

Monitor mental health

Because individuals with DCD are at risk for poor self-esteem, anxiety and depression, physiatrists can educate family members and the individual with DCD about community resources, which may include psychological counselling [15].

Conclusion

Physiatrists play a crucial role in the management of individuals with DCD. Collaborative efforts with PTs are a critical factor in examination and intervention leading to optimal care and outcomes for individuals with DCD and their families.

References

- (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Association, USA.

- Harris SR, Mickelson ECR, Zwicker JG (2015)Diagnosis and management of developmental coordination disorder. Can Med Assoc J 187(9): 659-665.

- Wilson BN, Neil K, Kamps PH, Babcock S (2013) Awareness and knowledge of developmental co-ordination disorder among physicians, teachers and parents. Child Care Health Dev 39(2): 296-300.

- Alonso SC, Hill EL, Crane L (2015) Surveying parental experiences of receiving a diagnosis of developmental coordination disorder (DCD). Res Dev Disabil 43(44): 11-20.

- Camden C, Wilson B, Kirby A, Sugden D, Missiuna C (2015) Best practice principles for management of children with developmental coordination disorder (DCD): Results of a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev 41(1): 147-159.

- Blank R, Barnett AL, Cairney J, Green D, Kirby A, et al. (2019) International clinical practice recommendations on the definition, diagnosis, assessment, intervention, and psychosocial aspects of developmental coordination disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol 61(3): 242-285.

- Dannemiller L, Mueller M, Leitner A, Iverson E, Kaplan SL (2020) Physical therapy management of children with developmental coordination disorder: An evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the academy of pediatrics physical therapy of the american physical therapy association. Pediatr Phys Ther 32(4): 278-313.

- Kirby A, Sugden D, Purcell C (2014) Diagnosing developmental coordination disorders. Arch Dis Child 99(3): 292-296.

- Henderson SE, Sugden DA, Barnett AL (2007) Movement assessment battery for children-second edition (Movement ABC-2). Pearson Assessment, London, England.

- Schoemaker MM, Niemeijer AS, Flapper BCT, Smits Engelsman BCM (2012) Validity and reliability of the movement assessment battery for children-2 checklist for children with and without motor impairments. Dev Med Child Neurol 54(4): 368-375.

- Wilson BNCS (2012) The developmental coordination disorder questionnaire 2007 (DCDQ’07). Administration manual for the DCDQ’07 with psychometric properties, Canada.

- Hendrix CG, Prins MR, Dekkers H (2014) Developmental coordination disorder and overweight and obesity in children: A systematic review. Obes Rev 15(5): 408-423.

- Cermak SA, Katz N, Weintraub N, Steinhart S, Raz Silbiger S, et al. (2015) Participation in physical activity, fitness, and risk for obesity in children with developmental coordination disorder: A cross-cultural study. Occup Ther Int 22(4): 163-173.

- Adams ILJ, Broekkamp W, Wilson PH, Imms C, Overvelde A, et al. (2018) Role of pediatric physical therapists in promoting sports participation in developmental coordination disorder. Pediatr Phys Ther 30(2): 106-111.

- Draghi TTG, Cavalcante NJL, Rohr LA, Jelsma LD, Tudella E (2020) Symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 96(1): 8-19.

© 2021 Lisa Dannemiller. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)