- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Open Access

Self-Directed Learning Skills of Undergraduate Physiotherapy Students: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Isha Akulwar-Tajane1* and Annamma Varghese2

1Assistant Professor in Neuro Physiotherapy, K J Somaiya College of Physiotherapy, Mumbai, India

2Professor in Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy, K J Somaiya College of Physiotherapy, Mumbai, India

*Corresponding author: Isha Akulwar-Tajane, Department of Neuro Physiotherapy, Mumbai, India

Submission: March 23, 2021; Published: April 21, 2021

ISSN 2637-7934 Volume3 Issue3

Abstract

Background: Self-Directed Learning (SDL) is an important form of adult learning and is at the core of undergraduate medical education. SDL skills and technology readiness are postulated as integral factors influencing individual behavior and academic performance in blended learning contexts. So far, the predominant instructor-led face-to face learning approach in traditional learning environments has not considered the importance of these factors. Recently, strict nationwide lock down for the COVID-19 closed educational institutions and ushered in online learning to continue learning. Students are facing uncertainties in the online learning context and need to adjust or formulate their own best learning strategies to suit this newly adopted model of ‘self-directed learning with technology’. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the SDL skills of Physiotherapy students.

Methodology: A cross-sectional online survey was conducted in undergraduate physiotherapy students. A semi-structured questionnaire was developed considering multiple dimensions of SDL skills and assessed students’ perception of their own SDL skills. 227 students voluntarily participated.

Result: Majority of the Physiotherapy students possess the fundamental qualities of SDL skills. However, students found it difficult to adapt to a new learning situation and expressed a sense of discomfort and insecurity in using online learning platforms. The other domain with low perceived skills was ‘self-control’ where students mentioned lack of focus, inconsistency in efforts and difficulty to overcome procrastination.

Conclusion: This study helped to identify aspects influencing students’ learning processes from their own perspectives and provided valuable insights into the special needs and behavior of students in the context of COVID-19 lockdown. Students’ perceived difficulty in their adaptation to online learning methods highlights the need for prior training with learning platforms, and a change in pedagogical approach.

Keywords: Self directed learning skills; Physiotherapy education; Online learning; Covid-19 lockdown

Abbreviations: SDL: Self-Directed Learning

Introduction

Blended learning creates a rich educational environment with multiple technologyenabled forms in both face-to-face and online teaching [1]. In the higher education context, effective integration of face-to-face and internet technology components determines the quality of course design and is the hallmark of effective education. Apart from educational technology strategy and structure, students’ characteristics are closely related to the learning effectiveness in a blended environment. Amongst many student characteristics, Self-Directed Learning (SDL) skills and technology readiness are postulated as integral factors influencing individual behavior and academic performance in blended learning contexts [2].

You learn at your best when you have something you care about and can get pleasure in being engaged. Howard Gardner

Self-directed learning is an important form of adult learning. In its broadest meaning,

SDL describes ‘a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of

others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying resources

for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating

learning outcomes’ [3]. In defining SDL, two aspects need to be explored: Firstly, SDL as a

process or method of learning [3,4], and secondly, personality characteristics that are required and developed as an outcome of SDL [5,6]. Knowles [7],

described two opposite poles of a continuum of learning, with

teacher- or other-directed (pedagogical) learning at one end and

self-directed (andragogical) at the other. According to Knowles

(1990), the pedagogical learner is dependent on the teacher to

identify learning needs, formulate objectives, plan and implement

learning activities and evaluate learning. The pedagogical learner

prefers to learn in highly structured situations such as lectures

and tutorials. Conversely, the andragogical learner prefers to take

responsibility for meeting his or her own learning needs. The

continuum of teacher-versus self-direction can be described in

terms of the amount of control the learner has over their learning

and the amount of freedom given to them to evaluate their learning

needs and to implement strategies to achieve their learning goals.

Learning preferably, should be self-initiated, with a sense of

discovery coming from within [8]. Ideally, as learners mature,

they move from a self-dependent personality towards one of selfdirection

and autonomy. Self-directed students have a stronger

willingness to achieve learning goals and are anticipated to involve

in learning activities more actively. Our role as educators is to

enhance the ability of learners to be self-determined in their studies

and foster motivations for learning that are internal than external.

Technology readiness is another critical dimension connected

with students’ learning in the blended environment [9,10]. It is

defined as ‘people’s propensity to embrace and use new technologies

for accomplishing goals in home life and at work’ and can have both

positive and negative facets [11]. Students with higher levels of

technology readiness hold a positive attitude toward technological

learning media and innovative platforms for communication. While

students with a sense of discomfort and insecurity in adopting

technologies may take a longer time to become efficient users of

online learning platforms.

In the world of technology, familiarity and proficiency with

technological tools became pivotal to complementing self-directed

learning styles [12]. Thus, taken together, it can be hypothesized that

the students who are more self-directed and with active attitudes

toward technology-based products are more motivated in adopting

online learning strategies and achieving their learning goals. With

this perspective, integrating technology can be anticipated to enrich

the traditional classroom learning by fostering SDL skills.

Context of the Study

According to the most recent recommendations, SDL is at

the core of undergraduate medical education. Many universities

are now placing specific emphasis on the development of SDL or

lifelong learning skills as one of the primary goals of university

education. SDL is an essential proficiency skill for medical

practitioners and as such has been adopted by many medical

schools as a part of curriculum. SDL is an efficient and effective

learning tool and multiple modalities in educational practice can be

used for providing SDL instruction such as problem-based learning,

group discussions, etc [13,14]. SDL is considered to be the most

appropriate educational approach to enhance life-long learning as

it enhances self-efficacy [15].

Students’ perceptions of SDL to a certain extent reflect the

learning effectiveness and learning experience of students in a

course. However, these relationships are dynamic in different

learning settings and need further exploration. At K J Somaiya

College of Physiotherapy, the curriculum is a 4.5-year program with

the course divided into 4 academic years. The curriculum is predetermined

with clearly defined learning objectives of each course

according to an established time frame. It has a classroom-setting

approach with all the learning activities guided and supervised by

one or more instructor/s. A variety of instructional approaches and

a number of learning activities, resources and workshops are offered

to help students build up their repertoire of SDL strategies. It is

expected that the components of hybrid curriculum may encourage

students’ self-directed learning; however, the curriculum is still not

free from teacher-centered culture as the teachers have high power

in deciding the learning process. Also, assessment and/or training

focused on SDL is not yet a component of existing curriculum or

course design. Further investigation is needed to verify the actual

level and readiness of students’ SDL. Furthermore, it is likely that

students will have varying levels of competence and confidence

with self-direction, especially those who spent years in a learning

context that was dominated by a teacher-directed approach to

learning.

SDL is considered to be a ‘Learner-centered approach’ with

‘Critical reflection’ as an intrinsic component of the process.

However, with the existing predominant instructor-led approach,

students may not be able to identify the strategies of SDL in which

they are strong or weak. Recognizing the deficiencies in their SDL

skills will help the students use the available resources effectively.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to help students identify

their strengths and weaknesses in SDL strategies, from their own

perspectives. More specifically students’ personal factors such as

their own intentions, attitudes and abilities are the main focus of

this study.

Rationale for the Study

It is assumed that the ability to learn independently in one

situation or context can be generalized to other settings [16,17].

According to Candy [16], learners may have a high level of selfdirection

in an area in which they are familiar, or in areas that are

similar to a prior experience [16]. However, it would be inadvisable

to assume that a person who possesses high levels of readiness

for self-direction in a given situation would still possess the

same amount of readiness in a new, unfamiliar context. Learners

may exhibit different levels of self-direction in different learning

situations due to different levels of academic self-concept. It is

therefore important that measuring SDL readiness needs to be

done within a specific context.

Readiness for SDL is individualized, which accounts for the

varying degrees along the continuum. The Staged Self-directed

Learning Model was developed to allow for the individual

differences inherent in such a continuum [18,19]. In evaluating selfdirected

independent study contracts with undergraduate nursing

students, identified that a negative experience resulted from either over-direction or under-direction from the teacher [20]. Evidence

has found that those students who have low readiness for SDL and

are exposed to a SDL project, exhibit high levels of anxiety, and

similarly those learners with a high readiness for SDL who are

exposed to increasing levels of teacher direction also exhibit high

anxiety levels [18,21].

Physical Therapy (PT) practice requires self-determined,

professional clinical decision making in the face of an everincreasing

body of knowledge [22]. Traditional classroom training

is the pervasive pedagogic approach and E-learning has remained

in the periphery of educational delivery in Physiotherapy programs

[23]. There is a concern that traditional instruction-based methods

of learning do not adequately prepare students for the challenges of

physical therapy practice [24], and it has long been acknowledged

that other modes of learning are needed in PT education [25].

Recently, strict nationwide lock down for the COVID-19 closed

educational institutions and ushered in online medium to continue

learning. Based on the previous literature, SDL and technology

readiness can impact learning motivation, and drive learning

behavior of students in blended learning environments [26].

Also, some preliminary evidence suggests that these factors have

different predictive values on learning effectiveness among online

and blended learning contexts [27]. So far, the predominant

instructor-led face-to face learning approach in traditional learning

environments has not considered the importance of these factors. It

is becoming evident that adoption of the new domain of instructional

delivery -web-based medium during COVID-19 lockdown has

inherent difficulties in terms of student characteristics. Students

are facing uncertainties in the online learning context and need to

adjust or formulate their own best learning strategies to suit this

newly adopted model of ‘self-directed learning with technology’.

Research exploring online learning has indicated that SDL skills

may assist the learner with the learning process in these contexts

[28]. Therefore, it is important to identify university students’ SDL

skills, to offer support and guide students’ behavior in the given

scenario.

Thus, this study aimed to determine the self-directed learning

skills of undergraduate Physiotherapy students in online context

with specific objectives outlined as

Primary objectives

To identify the areas of strength in self-directed learning skills

of undergraduate Physiotherapy students from I year -IV year

To identify the weak domain/s of self-directed learning skills of

undergraduate Physiotherapy students from I year -IV year

Secondary objective

To determine the relationship between self-directed learning skills and year of study (comparison between I year to IV year)

Research question

To achieve the objectives of this study, the following core

research question was formulated to guide the study:

Do undergraduate Physiotherapy students have self-directed

learning skills? What are the areas of their strength and weakness

in self-directed learning?

Research Hypothesis

Not applicable

Literature Review

The literature search conducted for the present study reviewed

existing perspectives on SDL and included articles published online

only. Although there is an emerging literature in physiotherapy,

the research is primarily from medical education. Some conclusive

findings are as follows:

The concept of self-directed learning has undergone thorough

consideration over the last years and a variety of perspectives on

SDL exist and researchers with different foci attempt to model

how cognitive, meta-cognitive, motivational, and contextual factors

influence the learning process. SDL is well defined in higher

education as a learner-centered approach and is an important

attribute of lifelong learners as it enhances self-efficacy [3,16]. SDL

and information and computer technology utilization are related in

many ways in learning context [1,11,29].

SDL skills assessment and training are widely adopted in many

medical schools. SDL as a learning tool is implemented using many

diverse approaches and teaching modalities [30-34]. Outcome

measures used include qualitative and quantitative tools [35-43].

Questionnaires are limited. Some questionnaires are generic for

adult learners such as Guglielmone (1977) ‘Self-Directed Learning

Readiness Scale’ (SDLRS) [35]. Other instruments are adopted for

specific disciplines such as Fishers’ self-directed learning readiness

score instrument for nursing education [37]. The instrument most

widely used in educational and nursing research to measure SDL

readiness is (SDLRS) [38,44-46]. SDL being difficult to assess using

direct measure tools; quantitative methods have been reported

in very few studies. These studies have used formal assessment

tools administered by faculty and include varied criteria of

standards. Not much empirical evidence is available in the extant

literature in Indian Physiotherapy education and there is a need for

Physiotherapy-specific research. Thus, the present study intends to

fill this gap in the literature.

Methodology

It was a cross-sectional descriptive study conducted during

COVID-19 lockdown period (May 2020). Ethical approval was

obtained from the institutional review board of K J Somaiya college

of Physiotherapy, India. All the undergraduate Physiotherapy

students (I -IV-year BPTh.) enrolled in this academic institute were

invited to participate in an online survey. We included students for

the same institutional background for better control of the survey.

We collected qualitative responses from students about their

perception in studies in the current academic year. During the time

of data collection, most of the teaching portion was completed and

students were engaged in studying for and taking university exams

in the upcoming month. Participation in the study was voluntary and electronic consent was obtained from the participant.

Students’ unwillingness to participate and students who were

transferred recently from other institutes were set as exclusion

criteria. Sampling method was non-randomized, convenient and

the target population is representative of students available on

social media platforms. Sample size was not estimated prior to the

study; however, a maximum number of participants was desirable

as well as anticipated in view of relevance of this topic to students

in the current situation; and the beneficial use of social media as a

method of data collection.

A questionnaire was developed de-novo as a part of this study.

This is a self-report measure and students were asked to reflect on

their SDL skills. Basic demographic details included age, academic

year, and some additional information on computer skills, internet

use, etc. The questionnaire is designed considering multiple

dimensions of SDL skills as evident in the literature. The literature

was extensively surveyed to compile a list of attitudes, abilities

and personality characteristics of a self-directed learner. The

questionnaire is semi- structured and has a combination of open

and close ended-questions (includes multiple choice and ranking

Likert-scale style questions). The questionnaire is in English

language. Content validity of the questionnaire was established

from two experienced teachers. The questionnaire was distributed

to the participants as Google forms via social media on WhatsApp;

and was emailed, if requested by them. Link to the forms was

available to them for seven consecutive days. Reminders were sent

to ensure maximum participation. Data thus collected was subjected

to analysis. This questionnaire can be used with permission from

the corresponding author and appropriate citation of study.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (percentage and frequency distribution) was performed. Open ended responses were analyzed through thematic analysis. From this multidimensional questionnaire, the areas where students are performing well and the areas where they might be lacking were identified. Preliminary data analysis was conducted to determine if the academic year of students influenced the results (as mentioned in secondary objective). Comparative analysis of academic year-wise four different groups revealed no significant difference, so all the participants were treated as a single group.

Result

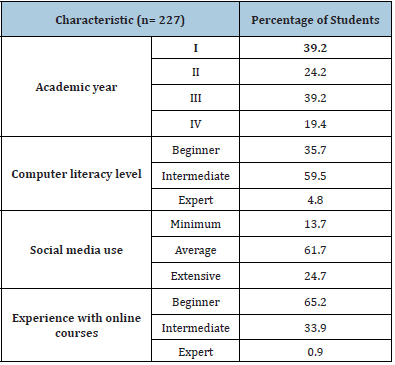

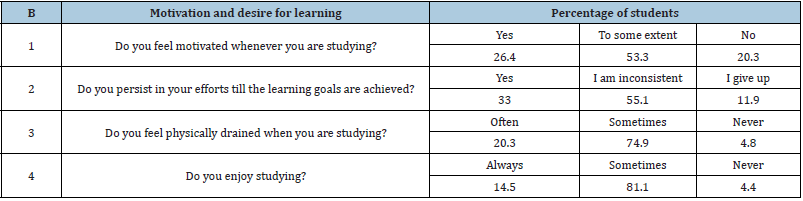

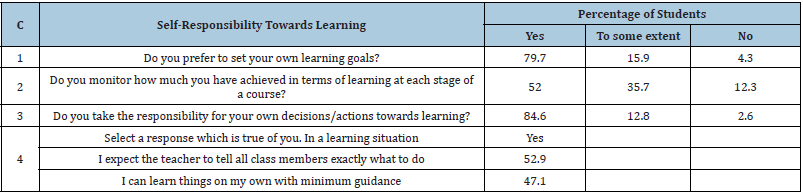

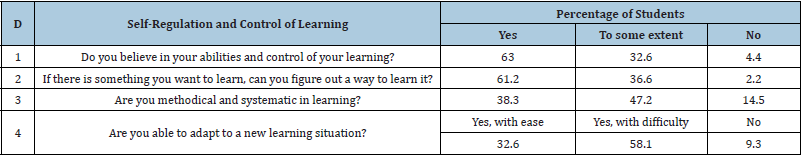

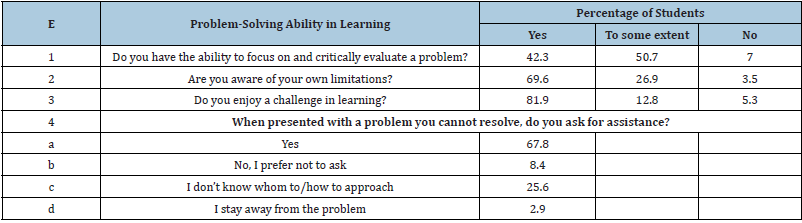

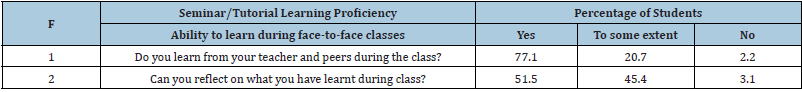

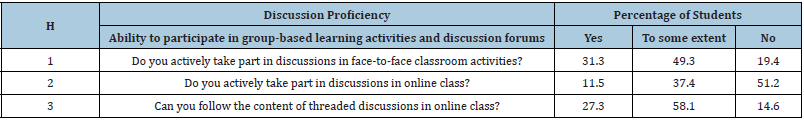

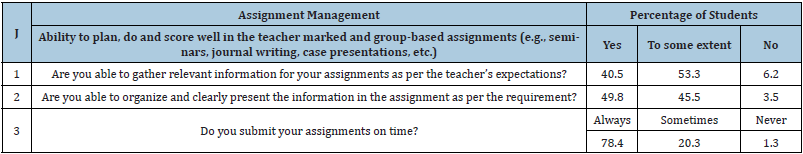

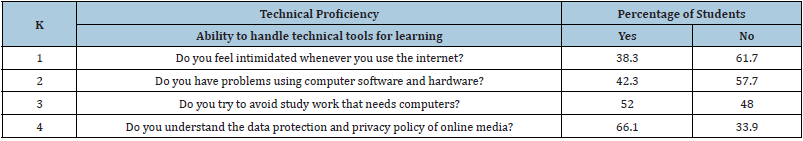

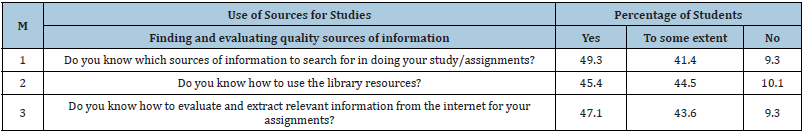

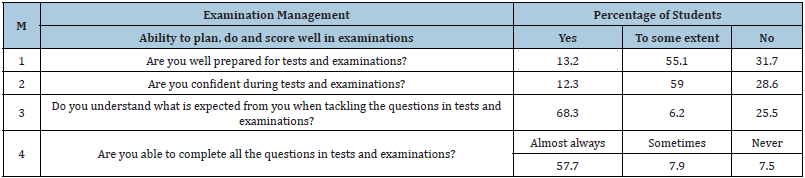

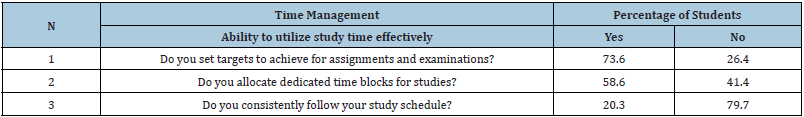

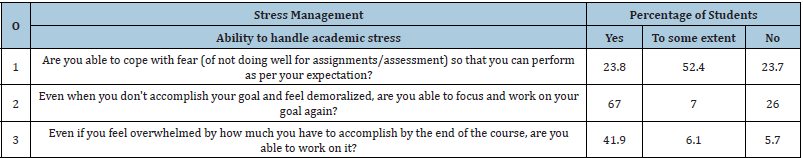

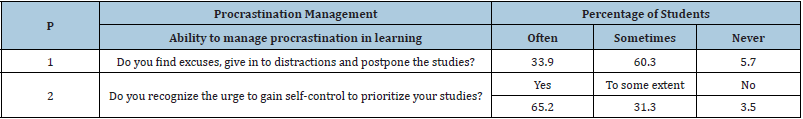

Out of the 280 forms distributed, 227 students submitted the filled forms yielding a response rate of 81.07%. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents. As seen from the table, academic year-wise participation was highest from I and III year followed by II and IV year, respectively. Majority of them had intermediate levels of computer literacy, average social media use and were beginners with online classes. Table 2 to 14 show the responses of the participants for each domain of the SDL skills. The following paragraph provides the key findings of the study. Majority of the participants were able to identify the learning goals and objectives of the course; had motivation and desire to pursue learning; however reported lack of focus and inconsistency in efforts. Majority of them were able to set the learning goals on their own; however, some reported that they wanted the teacher to tell them exactly what to do. Approximately one third of the participants perceived low self-efficacy in self-regulation and control of learning. Majority of them reported to have problemsolving ability; however, some of them reported that they do not know whom to or how to approach for assistance. Low learning proficiency, similarly, less active participation in discussions was reported in online classes as compared to face-to-face classes. Majority of them reported the ability for assignment work; ability to extract relevant information from library and internet sources; and comprehension competence. Majority of them were able to handle technological tools for learning; however, some of them reported that they avoid study work that needs use of computers. Some weaknesses were perceived in the domain of examination; time management; ability to handle academic stress and procrastination management.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 2: Learning goals

Table 3: Motivation and desire for learning

Table 4: Self-responsibility towards learning

Table 5: Self-regulation and control of learning

Table 6: Problem-solving ability in learning

Table 7: Seminar/Tutorial Learning Proficiency

Table 8: Online learning proficiency

Table 9: Discussion proficiency

Table 10: Assignment management

Table 11: Technical proficiency

Table 12: Comprehension competence

Table 13: Use of sources for studies

Table 14: Examination management

Table 15: Time management

Table 16: Stress management

Table 17: Procrastination management.

Comments from participants revealed some interesting perspectives on their experiences of different types of learning methods in physiotherapy as stated below:

P23

The reason for why we are supposed to learn subjects and certain topics and their actual application in physical therapy should be thought about which also might increase the interest of students!

P44

I would like the teaching to be more practical as in being taught how to relate the things we study for theory to be used practically.

P89

Can we get guidance on how we should focus on the studies and our timetable during the university exams?

P92

If exams must be taken, assignments-based examination will help us a lot, since it will relieve us of the mental stress and anxiety and also motivate us to learn more.

P126

Exams pressure should be lifted for ease learning. Also, this will cause more eagerness to learn new things rather than just mugging up.

P220

Online learning and classes are a bit difficult to understand as compared to classroom teaching!

These qualitative feedbacks further highlight the need for teaching to be more practical; some change in the examination pattern and need for mentoring to relieve academic stress and time management.

Discussion

Some scholars have recognized the importance of the learning

context for SDL (e.g., Candy) [16]. When initial SDL models were

developed, face-to-face instruction was the predominant mode

in higher education. Almost a decade after the last model was

developed (cf., Garrison), [47,48], higher education is occurring in a

variety of contexts, ranging from face-to-face classrooms to virtual

classrooms. Within each of these settings, a variety of methods may

be used to enable interactions, including 100% physical classroom

interactions to a blend of face-to-face and online interactions to

100% online interactions. While there are indications that selfdirectedness

is a desirable trait for online learners [48], we do not

have an adequate understanding of the impact of a specific learning

context (i.e., physical classroom instruction, a web-based course,

a computer-based instructional unit) on self-direction. There is a

need for new perspectives on how context influences SDL.

We aimed to determine the SDL skills with specific emphasis on

the online learning context to indicate the impact of environmental

factors on SDL. To summarize, the majority of Physiotherapy

students possess the fundamental qualities of SDL skills and year of

study did not cause a difference in SDL skills. This is in accordance

with previous study findings from a large cohort of undergraduate

students which included physiotherapy students [49]. However,

students found it difficult to adapt to a new learning situation

and expressed a sense of discomfort and insecurity in using

online learning platforms. The other domain with low perceived

skills was ‘self-control’ where students mentioned lack of focus,

inconsistency in efforts and difficulty to overcome procrastination.

It is generally believed that online learning gives more control

of the instruction to the learners [50,51]. In fact, some scholars

consider SDL critical in distance education settings with its unique

characteristic of the physical and social separation of the learner

from the instructor or expert as well as other learners [52]. Recent

research in an online distance education indicates that students

need to have a high level of self-direction to succeed in an online

learning environment [48]. In fact, not only does an online learning

context influence the amount of control that is given to (or expected

of) learners, but it also impacts a learner’s perception of his or her

level of self-direction. For example, in a recent qualitative case

study, Vonderwell & Turner [53] examined pre-service teachers’

online learning experience in a technology application course [53].

Participants in the study expressed that the online learning context

enhanced their responsibility and initiative towards learning. They

reported they had more control of their learning and used resources

more effectively.

On the contrary, we observed that students perceived low

efficacy in the online learning context. It has been suggested that

one of the most significant aspects for a successful informal learning

is to enable learners to control their own learning [54]. However,

learning through online resources might be demanding for learners

because of these self-control, monitoring, and management aspects.

Learners might suffer from the effort to reduce disorientation and

increase the quality of their learning outcomes [55]. This is the

reason why interest and engagement are essential for successful

self-directed informal online learning. Autonomous learners

should also consider the responsibility for a learning situation

[56]. For example, during the learning through online resources,

“lost-in-hyperspace phenomenon” often happens, which refers

to “experiencing disorientation due to information overload and

aimlessly following hyperlinks” [55]. This is the reason why the

learners need to control their own learning.

Also, there were a number of extrinsic influences for learning

online in a self-directed way. The study findings imply that the

online learning/teaching environment requires reconstruction of

student and instructor roles, relationships, and practices. Student

experiences showed that the online environment influenced their

learning. Preparing students for active engagement in learning

and collaboration needs to be emphasized in both face-to-face

and online environments. As mentioned previously, students’

perceptions reflect the learning effectiveness and learning

experience in a course. There is only limited research that

compares the effect of different educational approaches on selfefficacy

in higher education [57,58] In an experimental study on

undergraduate physiotherapy students, self-directed learning and

traditional instruction-based learning approach showed equal

study outcome & self-efficacy at the end of year two [23]. Results

of our study indicate that the present curriculum is still not free

from teacher-center culture. Student participants of this study had

spent years in a learning context that was dominated by a teacherdirected

approach to learning and the majority of the students were

beginners for the online course. This suggests that they may take a

longer time to become efficient users of online learning platforms.

It is critical to understand the pedagogical potential of online

learning for providing active and dynamic learning opportunities

for learners. Students’ perceived difficulty in their adaptation to

online learning methods highlights the need for prior training with

learning platforms, and a change in pedagogical approach.

This exploratory research helped to identify aspects influencing

students’ learning processes from their own perspectives and

provided valuable insights into the special needs and behavior of

students in the context of COVID-19 lockdown.

Social Relevance and Implications

The present study considers SDL skills as an important construct for effective implementation of blended learning. The study of SDL online can help identify those trans contextual SDL attributes as well as those unique online-based ones, enabling better online teaching and learning experiences. To develop an online environment further it is important to broaden the understanding of how students perceive online learning and to identify aspects influencing students’ learning processes and their adaptation to self-directed learning online and thus to know which aspects need to be reinforced. To enhance the strategies that students can use to improve their self-direction or self-regulation in learning (other than personal discovery, which is usually long and frustrating), useful strategies can be imparted to them through direct instruction, guided and independent practice, instructor feedback, peer support and pedagogical adaptation. The periodic implementation of the questionnaire developed as a part of this study will help the university undergraduate students enhance and improve academic self-concept, become actively engaged in the learning process, achievable, motivated, and optimistic in their academic life. Institute faculty will be able to apply the questionnaire of self-directed learning in their teaching assessments, which will facilitate their efforts to fulfill the required learning outcomes and enhance academic quality and excellence. Furthermore, selfefficacy in physical therapy practice, or task specific confidence, is considered critical to professional development of the novice PT [59-61] and is considered an independent predictor for student performance in clinical settings [59].

Implications in the short term

This study revealed many of the perceptions held by students that may form barriers to adopting SDL approaches. In the context of COVID-19 lockdown and online learning, this study assisted physiotherapy educators in the diagnosis of student learning needs, in order for the educator to implement teaching strategies that will best suit the students. This will promote an educational climate that will foster adult learning principles, gradually promoting student autonomy and mutual responsibility for learning in a nonthreatening environment and, hence, a reduction in student anxiety.

Implications in the long term

Exploring the SDL with a focus on technology readiness can deepen the understanding of blended learning course pedagogy design and can further provide insights into special needs and behaviors of students. Furthermore, this study has provided valuable data for curriculum development. Results of this study can serve to guide educators to optimize and integrate course design and adopt a proper instructional strategy in both online and offline teaching; thus, leading to improved learning outcomes. Integrating these skills and strategies in existing curriculum may potentially enhance the perception of students and can lead to more meaningful learning experience. The need for prior training or briefing of learning platforms; and emphasizing self-directed skills in students can be considered before implementation of blended learning approaches. These perceptions and the students’ comments serve to remind us how important it is for us as educators to be explicit in setting goals which incorporate SDL strategies and to provide the framework onto which students gradually graft their own experiences as they become self-directed lifelong learners.

Implications for research

Longitudinal research is needed to determine the long-term outcome which is more relevant for life-long learning. Students’ perceptions of SDL to a certain extent reflect the learning effectiveness and learning experience of students in a course. However, these relationships are dynamic in different learning settings and need further exploration. Overall, there is a need for more research on SDL-based on educational context and approaches because these approaches yet lack evidence-based support.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution of student participants; and support of the principal and research committee of the institute in the conduct of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Funding

The authors have not received any kind of financial support in the conduct or publication of this research.

References

- Geng S, Law KMY, Niu B (2019) Investigating self-directed learning and technology readiness in a blending learning environment. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 16(17).

- Collis B, Moonen J (2012) Flexible learning in a digital world: Experiences and expectations. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning 17(3): 217-230.

- Knowles M (1975) Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. New York: Cambridge Books, USA.

- Long HB (1990) Learner Managed Learning. Kegan Page, London, UK.

- Oddi LF (1986) Development and validation of an instrument to identify self-directed continuing learners. Adult Education Quarterly 36(2): 47-107.

- Oddi LF (1987) Perspectives on self-directed learning. Adult Education Quarterly 38(1): 21-31.

- Knowles M0 (1990) The adult learner: A neglected species. (4th edn), USA, p. 207.

- Rogers CR (1983) Freedom to learn for the 80s. Uganda.

- Piskurich GM (2003) Preparing learners for e-learning. Wiley, San Francisco, USA.

- Moftakhari MM (2013) Evaluating e-learning readiness of faculty of letters of Hacettepe. Master thesis. Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey.

- Parasuraman A (2000) Technology Readiness Index (TRI) a multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. Journal of Service Research 2(4): 307-320.

- Rashid T, Asghar H (2016) Technology use, self-directed learning, student engagement and academic performance: Examining the interrelations. Computers in Human Behavior 63: 604-612.

- Schmidt HG (1983) Problem-based learning: Rationale and description. Medical Education 17(1): 11-16.

- Atta I, Alghamdi A (2018) The efficacy of self-directed learning versus problem-based learning for teaching and learning ophthalmology: A comparative study. Advances in Medical Education and Practice 9: 623-630.

- Hong E, Neil OHF (2001) Construct validation of a trait self-regulation model. Int J Psychol 36(3): 186-194.

- Bonham LA, Candy PC (1991) Self-direction for lifelong learning. Adult Education Quarterly 42(3): 192-193.

- Guglielmino LM (1989) Reactions to field’s investigation into the SDLRS: Guglielmino responds to field’s investigation. Adult Education Quarterly 39(4): 235-240.

- Grow G (1991) Teaching learners to be self-directed. Adult Education Quarterly 41(3): 125-149.

- Tennant M (1992) The staged self-directed learning model. Adult Education Quarterly 42(3): 164-166.

- Richardson M (1988) Innovating andragogy in a basic nursing course: An evaluation of the self-directed independent study contract with basic nursing students. Nurse Education Today 8(6): 315-324.

- Wiley K (1983) Effects of a self-directed learning project and preference for structure on self-directed learning readiness. Nursing Research 32(3): 181-185.

- (2013) American Physical Therapy Association. Vision 2020.

- Lankveld W, Maas M, Wijchen J, Visser V, Staal JB (2019) Self-regulated learning in physical therapy education: A non-randomized experimental study comparing self-directed and instruction-based learning. BMC medical education 19(1): 50.

- Zimmerman B (2015) International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. Self-regulated learning: Theories, measures, and outcomes pp. 541-546.

- Solomon P (2005) Problem-based learning: A review of current issues relevant to physiotherapy education. Physiotherapy theory and practice 21(1): 37-49.

- Kintu MJ, Zhu C, Kagambe E (2017) Blended learning effectiveness: The relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 14(7).

- Chou P, Chen F (2008) Exploratory study of the relationship between self-directed learning and academic performance in a web-based learning environment. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration 11(1).

- Hartley K, Bendixen LD (2001) Educational research in the Internet age: Examining the role of individual characteristics. Educational Researcher 30(9): 22-26.

- Horton W (2006) E-learning by design. Pfeiffer, San Francisco, USA.

- Eva KW, Cunnington JP, Reiter HI, David R, Georffrey R (2004) How can I know what I don’t know? Poor self-assessment in a well-defined domain. Adv Health Sci Educ 9(3): 211-224.

- (2019) Education. Function and structure of a medical school.

- Morris TH (2019) Self-directed learning: A fundamental competence in a rapidly changing world. Int Rev Educ 65(4): 633-653.

- Gyawali S, Jauhari AC, Ravi SP, Saha A, Ahmad M (2011) Readiness for self-directed learning among first semester students of a medical school in Nepal. J Clin Diagnostic Res 5(1): 20-23.

- Premkumar K, Vinod E, Sathishkumar S (2018) Self-directed learning readiness of Indian medical students: A mixed method study. BMC Med Educ 18: 134.

- Guglielmino LM (1978) Development of the self-directed learning readiness scale. Dissertation Abstracts International 38(11): 6467.

- Oddi LF (1984) Development of an instrument to measure self-directed continuing learning. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Israel.

- Fisher M, King J, Tague G (2001) Development of a self-directed learning readiness scale for nursing education. Nurse Educ Today 21(7): 516-525.

- Wiley K (1983) Effects of a self-directed learning project and preference for structure on self-directed learning readiness. Nursing Research 32(3): 181-185.

- Williamson SN (2007) Development of a self-rating scale of self-directed learning. Nurse Res 14(2): 66-83.

- Shen WQ, Chen Hl, Hu Y (2014) The validity and reliability of the Self-Directed Learning Instrument (SDLI) in mainland Chinese nursing students. BMC Med Educ 14: 108.

- Cadorin L, Bressan V, Palese A (2017) Instruments evaluating the self-directed learning abilities among nursing students and nurses: A systematic review of psychometric properties. BMC Med Educ 17(1): 229.

- Lopes J, Miguel C (2017) Self-directed professional development to improve effective teaching: Key points for a model. Teaching and Teacher Education 68: 262-274.

- Stockdale SL, Brockett RG (2011) Development of the PRO-SDLS: A measure of self-direction in learning based on the personal responsibility orientation model. Adult Education Quarterly 61(2): 161-180.

- Kell OSP (1988) A study of the relationships between learning style, readiness for self-directed learning and teaching preference of learner nurses in one health district. Nurse Education Today 8(4): 197-204.

- Linares AZ (1989) A comparative study of learning characteristics of RN and generic students. Journal of Nursing Education 28(8): 354-360.

- Linares AZ (1999) Learning styles of students and faculty in selected health care professions. Journal of Nursing Education 38(9): 407-414.

- Garrison KR, Muchinsky PM (1977) Evaluating the concept of absentee‐proneness with two measures of absence. Personnel Psychology 30(3): 389-393.

- Shapley P (2000) On-line education to develop complex reasoning skills in organic chemistry. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 4(2).

- Tekkol I, Demirel M (2018) An investigation of self-directed learning skills of undergraduate students. Front Psychol 9: 2324.

- Garrison DR (2003) Self-directed learning and distance education. In: Moore MG, Anderson W (Eds.), Handbook of Distance Education. pp. 161-168.

- Gunawardena CN, Issac MS (2003) Distance education. In: Jonassen DH (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology. pp.355-395.

- Long HB (1998) Theoretical and practical implications of selected paradigms of self-directed learning. In: Long HB, et al. (Eds.), Developing paradigms for self-directed learning. pp. 1-14.

- Vonderwell S, Turner S (2005) Active learning and preservice teachers' experience in an online course: A case study. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education 13(1): 65-84.

- Burton RR, Brown JS (1979) An investigation of computer coaching for informal learning activities. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 11(1): 5-24.

- Scholl P, Benz BF, Böhnstedt D, Rensing C, Schmitz B, et al. (2009) Implementation and evaluation of a tool for setting goals in self-regulated learning with web resources. In: Cress U, et al. (Eds.), Lecture Notes in Computer Science pp. 521-534.

- Derrick MG (2003) Creating environments conducive for lifelong learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education pp. 5-18.

- Alt D (2015) Assessing the contribution of a constructivist learning environment to academic self-efficacy in higher education. Learn Environ Res 18(1): 47-67.

- Negovan V, Sterian M, Colesniuc G (2015) Conceptions of learning and intrinsic motivation in different learning environments. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 187: 642-646.

- Black B, Lucarelli J, Ingman M, Briskey C (2016) Changes in physical therapist Students’ self-efficacy for physical activity counseling following a motivational interviewing learning module. J Physical Therapy Educ 30(3): 28-32.

- Hayward LM, Black LL, Mostrom E, Jensen GM, Ritzline PD, et al. (2013) The first two years of practice: A longitudinal perspective on the learning and professional development of promising novice physical therapists. Phys Ther 93(3): 369-383.

- Jones A, Sheppard L (2012) Developing a measurement tool for assessing physiotherapy students’ self-efficacy: A pilot study. Assess Eval High Educ 37(3): 369-377.

© 2021 Isha Akulwar-Tajane. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)