- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

To Compare the Mean Percentage Improvement in Coordination, Strength and Disability in Overhead Throw Athletes with Partial Thickness Tear of the Rotator Cuff Following Plyometric Training in Different Phases of Rehabilitation

Ritika Patel and Anu Bangal*

Sports physiotherapist, India

*Corresponding author: Anu bangal, Assistant professor, Sports physiotherapist, Noida, India

Submission: November 11, 2017; Published: February 05, 2018

ISSN: 2637-7934Volume1 Issue3

Abstract

Background & Objectives: To compare the mean percentage improvement in coordination, strength and disability in overhead throw athletes with partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff following plyometric training in different phases of rehabilitation.

Methods: a total of 30 male overhead throwers suffering from partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff injury, on the basis of inclusion criteria were taken in the study. A full description of the study, including the selection process was explained to each patient. Documented consent was obtained from each patient. Group 1 consisted of athletes with history of rotator cuff injury one and half year back and group 2 included athletes with rotator cuff injury three months back. Coordination, strength and disability were assessed pre and post plyometric training for a period of three weeks and the mean percentage of improvement were compared in both the group following plyometric training.

Results: intragroup analysis showed a significant improvement in coordination, strength with the level of significance (p<0.05).

Discussion & Conclusion: group 1 showed an improvement in the mean percentage in coordination, the strength of supraspinatus muscle, and bench press when compared to the group 2. While the group 2 showed an improvement in mean percentage in the strength of the subscapularis, teres minor muscle and infraspinatus muscle when compared with the group 1.

Keywords: Partial tear of the rotator cuff; Plyometric training; Overhead throwers

Introduction

Prevalence of rotator cuff tear

Although an accurate incidence of partial thickness rotator cuff tears is unknown [1]. In the younger population (approximately 18-35 years), the patient most commonly is an overhead athlete involved in sports such a swimming, tennis, baseball, football, or javelin throwing. In overhead sports such as volleyball, baseball or tennis shoulder problems are very common [1-3].

Abnormal throwing biomechanics

The shoulder is significantly stressed in overhead athlete, especially during distinct phases of throwing motion. Throwing motion occurs in six phases and serves as a model of shoulder motion for most overhead sports. The phases are wind-up, early cocking, late cocking acceleration, deceleration and follow-through. The phases are separated by changes in load, shoulder position and the muscle firing pattern. During the throwing motion enormous stress is put on the dynamic and the static stabilizers of the shoulder.Symptoms maybe vague and the athlete may report only a gradual loss of velocity or control during competition often known as the dead arm syndrome [2,3].

Plyometric training

Plyometric are also referred to stretch -shorten exercise. The stretch stimulus body propioceptors such as the muscle spindle and Golgi tendon organs. The muscle spindle is stretch receptor located within the muscle belly. A quick stretch stimulus to the muscle spindle reflex produces a contraction of extrafusal muscle fiber in the agonist and synergist muscles [4]. This reflex is very rapid (0.3 to 0.5milli seconds). Stimulation of the GTO produces inhibition of the agonist extrafusal muscle fiber; therefore, the GTO protect against over contraction or over stretch of the muscle. During proper plyometric exercises, the excitatory effect of the muscle spindle reflex pathways overrides the inhibition provided by the GTO [4]. Plyometric can help players to strengthen the skills and to increase powers which are also referred to as "explosive -reactive" power training, neural adaptations usually occur when athletes respond or react as a result of improved coordination between the CNS signal and proprioceptive feedback [4].

Methods

A total of 30 male overhead throwers suffering from partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff injury, on the basis of inclusion criteria were taken in the study. A full description of the study, including the selection process was explained to each patient. Documented consent was obtained from each patient. Group 1 consisted of athletes with history of rotator cuff injury one and half year back and group 2 included athletes with rotator cuff injury three months back. Coordination, strength and disability were assessed pre and post plyometric training for a period of three weeks and the mean percentage of improvement were compared in both the group following plyometric training.

Inclusion criteria [5,6]

A. 15 male subjects with a history of dominant hand rotator cuff injury for one and half years.

B. 15 male subjects with a history of dominant hand rotator cuff injury three months back.

C. Athletes, who gave a previous history of pain on the dominant shoulder while sleeping, reduced external rotation, abduction and difficulty in performing overhead activities.

D. Athletes who could perform a free weight bench press equal to the body mass or hand clap push- ups (upper extremity).

Exclusion criteria [5,6]

A. Patients with traumatic glenohumeral dislocation, fracture dislocation, instability, and other insignificant intra- articular disorders such as synovial chondromatosis associated with rotator cuffs and diabetes mellitus

B. No prior surgery to the shoulder joint.

Instrumentation

A. Dumbbells

B. Supine bench press set up

C. Stop watch

D. Tennis ball

E. Measuring tape

F. 2lb medicine ball

G. Assistant

Procedures

Strength [7]

The gold standard for muscular strength testing is the 1 RM. Kramer and Fry (1995) suggest the following protocol for 1RM testing. The test procedure begins with a warm-up of 5-10 repetitions at 40% to 60% of the client's estimated maximum. After a brief rest period, the load is increased to 60% to 80% of the client's estimated maximum, attempting to complete 3-5 repetitions. At this point a small increase in weight is added to the load and a 1RM lift is attempted. The goal is to determine the client's 1RM in 3 to 5 trials. The client should be allowed ample rest (at least 3-5 minutes) before each 1RM attempt.

Bench press

Procedure: The subjects were asked perform an adequate warm up. They were asked to warm up with 5-10 reps of a light- to-moderate weight, then after a minute rest perform two heavier warm-up sets of 2-5 reps, with a two-minute rest between set, then perform the one-rep-max attempt with proper technique. If the lift was successful, they were asked to rest for another two to four minutes and increase the load 5-10%, and attempt another lift. If the subject failed to perform the lift with correct technique, rest two to four minutes and attempt a weight 2.5-5% lower. They were asked to increase and decrease the weight until a maximum lift is performed. Selection of the starting weight was crucial so that the maximum lift was completed within approximately five attempts after the warm-up.

Coordination test [8]

The objective of the test was to monitor the athlete's Hand Eye coordination skill. This test required the athlete to throw and catch a tennis ball with the help of an assistant. The athletes were asked to warm up for 10 minutes. The athlete stood two meters away from the assistant. The assistant gave the command "GO" and started the stopwatch. The athlete threw the tennis ball with their right hand against the assistant and caught it with the left hand, the assistant threw the ball with the left hand and the athlete catches it with the right hand. This cycle of throwing and catching was repeated for 30 seconds. The assistant counted the number of catches and stops the test after 30 seconds. The assistant recorded the number of catches

Training Protocol [9]

A. Starting Position- Elbow Pronated to 90deg of Flexion.

B. Shoulder 90deg of Abduction.

Plyoball exercises : Internal rotation

The subjects were asked to throw the ball against the assistant and catch it back which allowed an eccentric contraction of the internal rotators to slowly decelerate the ball to the starting position, the subjects then used a quick concentric contraction of internal rotators to repeat the sequence.

Plyoball exercise : External rotation

The shoulder of the subjects was initially placed at 90deg of abduction and maximum internal rotation and elbow is flexed to 90deg. If the subject complained of no discomfort he was asked to progress to 90deg of shoulder abduction with maximum internal rotations the ball was thrown back the athlete caught the ball and eccentrically used the external rotators of the shoulder to decelerate the ball back to the start position

Plyoball exercise : Reverse throw

Position the assistant was behind the athlete who was half kneeling and tossed the athlete the ball The athlete caught the ball with 90deg of shoulder abduction with maximum shoulder external rotation, 90deg of elbow flexion and scapular retraction. The athlete decelerated the ball with an eccentric contraction of the posterior shoulder musculature into a position of shoulder adduction, internal rotation and elbow extension.

Progression of Medicine Ball Exercises

First phase was the warm up phase which involved throwing at a distance of 30-40 feet. Next progression distance was 30ft-180ft (5sets x 50/60reps). Advanced to the next phase only if the athlete completed 50-75reps. When the athlete completed about throwing the ball to 180 feet (3-5 sets x 50/60reps) without pain, the athlete was asked to initiate unrestricted throwing. Unrestricted throwing was achieved when the athlete can throw at a distance of 180ft (1set x 75reps) without pain.

Plyometric push-up- procedure- sets X reprtions -3X10 [10]

The subjects in group 1 started with their trunk vertical and their arms relaxed and hanging at their sides. From this position they allowed themselves to fall forward, extending their arms forward with slight elbow flexion, in preparation for contact. At contact, the subject gradually absorbed the force of the fall by further flexing the elbows and gradually stopped the movement with the chest nearly touching the floor. Immediately after stopping the downward motion, the subject reversed the action by rapidly extending her arms and propelling his trunk back to the starting position. A plyometric push-up was repeated every 4 seconds until the assigned repetitions were completed.

Dynamic push up [10]

The subjects in group 2 started up or inclined positioned with their hands placed just beyond the shoulder and their fingers were pointed forward. When viewed from the side the hands fell directly below the shoulder. The subject than lowered the body until the chest touched the floor. Immediately, the subject changed the direction and straightened the arms and pushed the trunk up to the start position. Post test measurements was taken after 3 weeks for both the groups.

Result

A total of 30 male overhead throwing athletes with a history of partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff after fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in this study. 15 athletes were divided into two groups. The mean percentage improvement in coordination, strength and disability were compared between both the groups following plyometric training for a period of 3 weeks.

Intragroup analysis

Group 1: in group one plyometric training using a medicine ball and plyo push ups were given for three weeks for overhead throwing athletes with a history of partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff one and half years back. Interpretation through data analysis was done by using t-test within the group.

Group 2: in group two plyometric training using a medicine ball and dynamic push ups were given for three weeks for overhead throwing athletes with a history partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff three months back. Interpretation through data analysis was done by using t-test within the group.

A. Co-ordination: for group 1, the mean for pre-test and post test are 35.8667 and 38.0667. The standard deviation for the pre test and post test are 1,76743 and 2.52039. The calculated t values are 6.736. Therefore when the calculated t values were compared with the t table it was found out to be more than the calculated t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in coordination following three weeks of plyometric training in healthy overhead athletes. For group 2, the mean for the pre test and post test are 34.1333 and 35.8667. The standard deviation for the pre test and post test are .91548 and .83381 the calculated t values are 11.309. The calculated t values were compared with the table and it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in coordination following three week plyometric training in athletes with partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff.

B. Subscapularis: For group 1, mean for pre test and post test are 7.6667 and 9.0667. The standard deviation for the pre test and post test are .81650 and .79881. The calculated t value is 8.573. Therefore when the calculated t values were compared with the t table it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in the strength of the subscapularis muscle following three weeks of plyometric training in healthy overhead throw athletes. For group 2, the mean for the pre test and post test are 6.5333 and 7.8000 the standard deviation for the pre test and post test. 91548 and 77460. The calculated t value are10.717 the calculated t values were compared with the table and it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in the strength of the subscapularis muscle following three week plyometric training in overhead throw athletes with partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff.

C. Supraspinatus muscle: For group 1, the mean for the pre test and post test are 8.2000 and 9.5333. The standard deviation for the pre test and post test are .77460 and .51640. The calculated t value are 10.853.when the calculated t values were compared with the t table it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in the strength of the supraspinatus muscle following three weeks of plyometric training in healthy overhead throw athlete. For group 2, the mean for the pre test and post test are 8.0000 and 9.1333.the standard deviation for the pre test and post test are .84515 and .91548. The calculated t values are 12.475. The calculated t values were compared with the table and it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in the strength of supraspinatus muscle following three week plyometric training in overhead throw athletes with partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff.

D. Bench press: For group 1 the mean for the pre test and post test are 14.2667 and 16.0000. The standard deviation for the pre test and post test are 1.38701 and 1.25357. The calculated value is 11.309. The calculated t values are 4.036. Therefore when calculated t values were compared with the t table it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in bench press following three weeks of plyometric training in healthy overhead throw athletes. For group 2, the mean for the pre test and post test are 13.9333 and 15.6667.the standard deviation for the pre test and post test are 0.88372 and 0.97590. The calculated t values are 14.666.The calculated t values were compared with the table and it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in bench press following three week plyometric training in overhead throw athletes with partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff.

E. Teres minor and infraspinatus: for group 1, the mean for the pre test and post test are 9.0667 and 9.8000. The standard deviation for the pre test and post test are 0.79881 and 0.41404. The calculated t values are 4.036. Therefore when calculated t values were compared with the t table it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in the strength of the teres minor and infraspinatus muscle following three weeks of plyometric training in healthy overhead throw athlete for group 2.The mean for the pre test and post test are 9.0000 and 9.8667. The standard deviation for the pre test and post test are .65465 and .35187. The calculated t values are 6.500. The calculated t values were compared with the table and it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in the strength of the teres minor and infraspinatus following three week plyometric training in overhead throw athletes with partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff.

F. Dash (Sports Module): the mean for the pre test and post test are 14.00 and 3.20. The standard deviation for the pre test and post test are 4.342 and 3.840. The calculated t values are 9.000. The calculated t values were compared with the table and it was found to be more than the t value (p<0.05). Hence there is a significant improvement in Dash (Sports Module) following three week plyometric training in overhead throw athletes with partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff.

Discussion

Improvement in strength

Statistically significant difference was observed on the strength parameter in both the groups in different phases of rehabilitation. Similar findings are available in the literature using different equipment used in plyometric training such as medicine ball, therabands, plyoback [9,11-14]. The use of medicine ball has been favorable for the improvement in muscular performance as per the available literature. Mcann et al. [15], studied the descriptive reports of electromyographic activity in the rotator cuff and scapular musculature and demonstrated favorable activation of these muscles using a medicine ball. Oliver et al. [16], also discussed the use of plyometric medicine ball to return to sport after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Gerald et al. [17], too employed the use of weighted medicine ball drills for the management of shoulder impingement injures in athletes. Courtney et al. [18], in their case study, used a green medicine ball weighing 1.5lb which was initiated in 2 weeks for a patient with little leaguers shoulder. Cordasco et al. [19], performed an electromyographic analysis of the shoulder during a medicine ball throw which indicated during the acceleration phase of the medicine ball the upper trapezius and lower subscapularis muscles had very high levels of activity and in the deceleration phase the rotator cuff demonstrated moderate activity. These findings supported the use of medicine ball training as a bridge between static resistive training and dynamic throwing in the rehabilitation of the overhead athlete. This training technique provided a protective method of strengthening that closely simulates portions of the throwing motion. Thus in our present study we used weighted ball (2lb) to improve the strength of the rotator cuff muscles by enhancing the neuromuscular control. During catching and throwing of the weighted ball, the adductors, internal rotators were eccentrically loaded and hence stretch was followed by a concentric cycle.

To the best of my knowledge no studies are available in the literature using plyometric training in rotator cuff injured patients treated conservatively. In our current study, the intragroup analysis showed statistically significant improvement in the muscle strength of the internal rotator for the subjects in group1. The findings in the present study favour the previous study done by they studied the effects of a high volume upper extremity plyometric training (8 weeks) on throwing velocity and functional strength ratios of the shoulder rotators in 24 collegiate baseball players. There was a statistically significant difference in the peak torque values at 180deg /sec in concentric IR pre to post training in the plyometric group (p=0.006) and also at 300deg/sec in concentric IR pre to post training in the plyo group (p=0.045) following 8 weeks of plyometric training (ballistic training). The mean percentage improvement in peak torque for the concentric IR at 180deg/sec was 15.5% and the mean percentage improvement for the concentric IR at 300deg/sec was 15.7%. While in our current study the mean percentage improvement in strength for the internal rotators was 17.9% for group 1. In our study, the reason for improvement in the mean percentage strength for the internal rotators were because firstly, since the athletes had a history of rotator cuff injury , the pre level values of the subjects in our study were less and hence showed greater values in the strength of the internal rotators post plyometric training. Secondly, in the above study, the strength of the internal rotators was assessed with an isokinetic dynamometer specific to 180deg/sec and 300deg/sec; in our current study we used 1RM to assess the strength of the internal rotator cuff muscle. And lastly, in the above study, high intensity ballistic training was used which could have led to micro trauma.

Heiderscheit et al. [20] studied the effects of isokinetic versus plyometric training on the shoulder internal rotators for a period of 8 weeks. The plyometric groups were trained on the Playback System. However no significant improvement was observed following plyometric training protocol using a 1.36kg (3lb) ball. The possible reasons could be firstly, subjects included in the study were not trained; secondly, the guidelines on the number of sets, repetitions, sets, rest period were not followed. Finally, since the subjects were healthy, the plyometric training should be performed at a maximal intensity for gains to occur. Our current study focused on post rotator cuff injured athletes, we used proper guidelines in terms of the sets, repetitions and rest period, and finally though we worked on a low intensity programme, keeping the reoccurrence of injury in mind, we used a medicine ball of 2lb gradually increasing the distance of throw hence significant improvement in the strength of the internal rotators were seen. In the above two available literatures, isokinetic device was used to assess the strength of the internal rotators. It has been stated by the authors that isolated isokinetic strength assessment was not an ideal method of evaluating the effectiveness of plyometric training, in our current study the protocol we used 1RM to assess the strength of the internal rotators. Hence an improvement in the strength of the internal rotators were seen Chad fortune et al. [21], also studied the effects of plyometric training on 38 healthy overhead athletes using plyoback system which included throwing of a weighed ball at the centre of the trampoline using a one handed overhead throwing motion. The results support our findings, as in our current study also significant improvement in the strength of the internal rotators were seen after the use of a 2lb medicine ball and medicine ball throw in various throwing positions were done for a period of three weeks. Similarly, statistically significant difference in the strength of the internal rotators was observed in group 2.

The mean percentage improvement in the strength of the internal rotators in group 1 was 17.9%, and the mean percentage improvement in the strength of the internal rotators in group 2 was 17.7%. And on statistical analysis while comparing the pre mean values in both the groups of the subscapularis muscle, significant difference was observed, the possible reason for the group1 to show a high mean percentage value when compared with group 2 was because the athletes in group one had a history of rotator cuff injury of one and half years, the healing would have already occurred and hence they had returned back to sports improving the strength of the internal rotators [22,23]. The subjects in group 2 had a history of rotator cuff injury 3 months back and they had not returned back to sports hence for this reason subjects in group 2 were given dynamic pushups while group 1 were given plyo pushups. The improvement may also be due the greater workload that was required in plyometric push up programme in group 1, the greater workload was attributed to the momentum of the falling trunk which contributed to the resistance provided by the individuals body weight and hence was overcome by the upper extremities during plyometric pushups. Because the kinetic energy the subject must overcome is the is a function of mass and velocity, the greater velocity of the falling trunk results in greater work to decelerate and then accelerate the body during plyometric push up (work = kinetic energy = half mv2) [10,24] Therefore from Wolffs law, more the applied load better would be the improvements.

Our current finding are in support of the results by Jeffery F et al. [10], they compared the effects of dynamic push up and plyometric pushups on upper body power and strength. The plyo push up group experienced statistically greater improvement than the dynamic group on medicine ball put (P=0.003) Intragroup analysis showed statistically significant difference in the strength of the external rotator muscles. The mean percentage value in group 1 for external rotators were 7.8 and the mean percentage value in group 2 was 9.25, the mean percentage improvement was found to be more in group 2 subjects when compared to group 1. Our findings were similar to that of Courtney et al. [19] who reported the outcomes of a young throwing athlete with little leaguers shoulder following plyometric rehabilitation of 5-week span that was divided into acute and sport specific rehabilitation phases. The strength of the external rotator at visit 1 was 3+/5, on visit 7 were 4+/5 and on visit 15 was 5/5. Improvement in the strength of the external rotators were mainly because the plyometric training with the use of a 1.5lb medicine ball was initiated at the second week of rehabilitation and the weight of the ball was progressed to 3lb along with progression in repetitions every week, Secondly the plyometric used also implemented the scapula-thoracic muscle activity which is an imperative component for secondary shoulder disorders. And lastly, the use of a body blade for enhancing neuromuscular control was done. In our current study though progression in plyometric training in form of progression in the weight of the medicine ball was not done but the increase in the distance of throw and repetitions were performed and secondly along with open chain kinetic exercises we even focused on close chain exercise such as push up which increased the applied load on the shoulder joint resulting in improvement in the strength of the external rotator.

Similar findings were seen in a case study done by Jason et al. [24], where an improvement in the strength of the external rotators were seen in a golf player after a rotator cuff repair. However immediate post -operative details were not provided by the author and the length of the supervised physical therapy was not reported by the treating therapists. Plyoball throws to a rebounder were the first plyometric exercise chosen to increase power. These low intensity exercises were progressed to a greater intensity by increasing the weight of the medicine ball. At the 3 month follow up, the golfer demonstrated 4/5 strength (traditional manual muscle testing positions) of the shoulder external rotators. 12 similarly in our study we worked on subjects with a history of rotator cuff injury, we used 1RM to evaluate the strength of the rotator cuff muscles and low intensity medicine ball throws were performed for duration of three weeks targeting the muscles needed for different positions of throw. Hence from the above literatures significant improvement was seen in the strength of the external rotators after 3 weeks of plyometric training.In our current study, statistically significant difference was observed in bench press parameter in both the groups following plyometric training.

In our current study, statistically significant difference was observed in bench press parameter in both the groups following plyometric training. Our findings were similar to Evans et al. [25], who determined that upper body power could be enhanced by performing a heavy bench press set prior to an explosive medicine ball put [25]. Possible reason for improvement could be because dynamic athletic performance requires training strategies that train both the force and velocity components of the force velocity curve. Complex training such as bench press and pushups combines the effect of strength work and speed work for optimal training effect, which hence creates possible neurogenic and myogenic changes [25-28] Plyometric training followed by complex training is believed to increase the excitation of the motor neurons and enhanced involvement of the nervous system. In our current study, according to the guidelines for initiating plyometric training, subjects who could perform bench press were included in our study.

Evidence does not exists regarding the best combination of weight training and plyometric training or how one form of training could affect the other if performed in a sequence. In our current study, we believe that improvement in the bench press would have followed the same principle of medicine ball drills followed by plyo pushups. Similarly Rajamohan et al. [27] studied the effects of complex (squats and jump squats) and contrast training (bench press and plyo pushups) on thirty young male athletes, aged 1921 years for 3 months duration (4 days/week) concluded that the contrast training group exhibited significant improvements. Hence relating the above mechanism with our current results, there was an improvement in bench press following plyometric pushups and medicine ball throws, the subjects in our study performed 3 sets of 10 reps plyo pushups after medicine ball throws for three weeks. This study support the use of contrast training to improve the upper body explosive levels in young players.

The mean percentage value for bench press in group 1 was 12.48 and the mean percentage value for bench press in group 2 was 11.9. On observing the mean percentage values of improvement in bench press group 1 showed better results as subjects included in this group had returned to sports and secondly, plyo pushups (a more aggressive form of plyometric training) was included in the regime so they showed a better result. Regardless on the form of progression used in our current study, we stressed on proper throwing mechanics during the progression throw. In clinical setting, where our study was carried out, low intensity plyometric training with smaller work-rest ratio (1:1) been followed, and 4872 hours of rest was advised for recovery between the plyometric sessions. We increased the distance of medicine ball throw from 30 feet to 180 feet which gradually increased the loads of the shoulder joint which hence helped in maintaining shoulder flexibility and muscle strength of the rotator cuff. Hence plyometric training when introduced in different phases of rehabilitation proved to be beneficial in gradually increasing the applied loads to the shoulder while using proper throwing techniques.

Improvement in Coordination

Statistically significant difference was observed on the coordination parameter in both the groups in different phases of rehabilitation. To my best knowledge, literatures available only mentions in form of muscle physiology as to how muscular coordination is gained following plyometric, our findings supported the study of Kevin et al. [8], who observed that athletes performing stretch shortening exercise drills like plyometric have accelerated muscular performance gains. These accelerated performance gains were not from morphologic change but rather from neural adaptation and enhanced neuromuscular coordination which was achieved after plyometric training.1 explosive plyometric training would have improved neural efficiency and increase neuromuscular performance, hence by utilizing this pre-stretch response would have allowed the athletes to better coordinate the activities of the muscle groups , which could be considered why in our current study the athletes in both the groups benefitted from plyometric to improve coordination, this enhanced neuromuscular coordination could had led to greater net force production , even in the absence of morphological changes within the muscle itself, referred to as neural adaption [8-29].

Nicole CJ [28] studied the mechanism the dynamic restraint system relies on feed-forward and feedback motor control to anticipate and react to joint movements or loads [28]. Feed-forward strategies employ muscle pre activation to "stress shield" articular structures and are organized based on previous experience with sport-specific activities. Functional training techniques with repetitive deceleration activities may create plastic neurologic adaptations to motor programs that improve coordination for both performance and dynamic restraint. The feedback motor- control process encompasses a number of reflexive pathways that continuously modify muscle activity to accommodate unanticipated events. Because the extremity is subjected to high joint loads and velocities during plyometric activities, these exercises are ideal for enhanced feedback motor control8 in our current study we utilized closed chain exercises too like pushups and bench press, which we believed the athlete was subjected to high joint loads and velocities hence enhanced motor feedback control which improved neuromuscular coordination. Our present study, the intragroup and intergroup analysis showed a significant improvement in coordination after plyometric training. This may be attributed to the reflex mechanism resulting in coordination activity as studied by Nicholas T 16. Who stated that these reflex mechanisms called "length feedback" and "force feedback" resulted from neural signals generated my muscle receptors that project back to the muscle of origin as well as the other muscles. The signals generate by the muscle stretch are called length feedback and those generated by force are called force feedback. The force feedback responsible for motor coordination is provided by the stimulation of the golgi tendon organ, that connects muscles across different joints and exert a torque in different direction through inhibitory feedback. Together, the length and force feedback induced during the loading phase of a plyometric activity have the potential to improve neuromuscular control [8,29].

Improvement in disability

Currently, however, few shoulder specific functional outcome assessments have been validated for use with athletes. Tools that include athlete-specific components include the DASH sports module which was used in the current study to assess the disability level of the athlete before and after the plyometric training protocol. Meller R [30] postulated that instruments such as these reflect the specific aim of clinicians in sports medicine, to return athletes to their pre injury level of sport/activity; therefore they will remain critical components of our practice [30]. An improvement in SM-DASH in this study was an expected finding as this measure applied directly to the patients performance in sports. Significant improvement in SM-DASH was observed in group 2 after plyometric training which was similar to the findings of Gabreil et al they used the SM-DASH before and after the rehabilitation of a young swimmer suffering from supraspinatus tendinopathy, and observed the initial SM -DASH score was 68.75 and the final score after 8 weeks was 6.25. This signified that there was an improvement in the disability level of the athlete after plyometric training combined other forms of exercises. In our present study Intragroup analysis showed a significant improvement in the disability level of the athletes under group 2 following plyometric training along with dynamic pushups for a period of 3 weeks. The pre mean value of SM- DASH in group 2 was 14 and the post mean value was 3.20. Which was similar to the findings of Saures et al [31] they used the DASH sports module to show how in soft ball players lead to a improvement in the health related quality of life. Respondent rating of shoulder pain correlated significantly with the DASH total (r = .69) and sports module (r = .69) [31-36].

The positive results in our study could be because we were working on post injured overhead throw athletes, our training programme focused on the training of the muscles that were required for a throw. With the help of plyometric training with proper guidelines the disability level ofthe athlete improved. A study done by Courtney P [19], demonstrated a meaningful improvement in the SM-DASH. It was possible that the sport specific plyometric rehabilitation may have provided an additional benefit for the athletes ability to return to sport, but authors have mentioned that a definite conclusion regarding treatment effectiveness are limited.9 In our study, group 2 showed an improvement in disability level after plyometric training was because they had a history of rotator cuff injury 3 months back and they were under the process of healing during the three months, hence after the plyometric training an improvement in the disability level was seen [37,38]. The subjects in group 1 were functionally active and they had no complaints of any sort of disability, hence their status of disability was not checked [39].

This study showed that a three week plyometric training programme could enhance the strength, coordination and disability of the overhead throwing athletes with partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff in different phases of rehabilitation [40]. the mean percentage improvement in coordination, strength of the supraspinatus and bench press were more in group1 when compared to group 2, while there was a mean percentage improvement in the strength of the subscapularis ,teres minor and infraspinatus muscle for group 2 were more when compared to group 1[41-43].

Future Scope

a) This study can provide the coaches and trainers with a sound scientific basis for further improvement in the quality, effectiveness and appropriate training programme for overhead throw athletes.

b) With the respect to sports physical therapist, the knowledge and the use of specific exercises involved in plyometric training will enhance the preventive and rehabilitative care of overhead throwers.

c) Research is needed to determine if the mechanisms involved in stretch- shortening cycle are similar between the lower extremity, upper extremity and trunk and to demonstrate that the upper extremity and the trunk receive comparable benefits from plyometric training. Despite of the lack of evidence documenting the effectiveness of plyometric exercise in rehabilitation, the clinical success of properly applied plyometric exercise warrants the continued use and research of this therapeutic intervention.

Conclusion

Plyometric training for three weeks including plyometric push up and dynamic pushups may be beneficial in improving the strength, coordination and disability in overhead athletes with partial thickness tear in different phases of rehabilitation.

Limitation

A. The entire kinetic chain includes the trunk, elbow, wrist and the lower extremities which should be significantly strengthened. Kinetic chain abnormalities including pelvic abductor weakness, lead leg quad tightness and hip internal rotation loss which should also be recognised. Proximal kinetic chain abnormalities evoke distal limb "catch up" and merely increase the demand on the shoulder. The strengthening of the lower extremities and core muscle exercises were not performed in our study

B. Since in our current study, the subjects in group 1 had returned to sports, appropriate progression via volume, and intensity should have been considered and the use of therabands and sports cords should have been considered in the warm up phase in order to work on the flexibility of the rotator cuff muscles.

C. The sample size is small

D. No control group

E. The training protocol should have been for a longer duration

F. Follow up should have been done

Appendix

Sm-Dash

Sports/performing arts module: The following questions relate to the impact of your arm, shoulder or hand problem on playing your musical instrument or sport or both. If you play more than one sport or instrument (or play both), please answer with respect to that activity which is most important to you. Please indicate the sport or instrument which is most important to you.

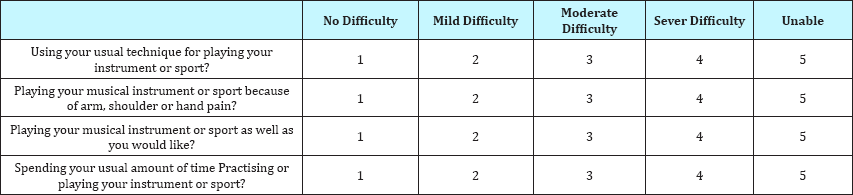

Scoring the optional modules: Add up assigned values for each response; divide by 4 (number of items); subtract 1; multiply by 25. Please circle the number that best describes your physical ability in the past week. Did you have any difficulty: (Table 1)

Table 1: Sports/Performing Arts Module.

Clinical Relevance in Practice

As we know that shoulder injuries are more prevalent in overhead throwers and is an area of concern in the field of sports physical rehabilitation, this present study with a short duration can benefit the overhead throwers to an early return in sports and can add on to the available literatures in relation to the different phases of rehabilitation in overhead throwers.

Acknowledgement

Working on this thesis has been a wonderful and often overwhelming experience. It is hard to say whether it has been grappling with the topic itself which has been the real learning experience, or grappling with how to write papers and proposals, give talks, work in a group, stay up until the birds start singing, and stay focus. It gives me great pleasure in expressing my gratitude to all those people who have supported me and had their contributions in making this thesis possible. First and foremost, I must acknowledge and thank The Almighty God for blessing, protecting and guiding me throughout this period. I could never have accomplished this without the faith I have in the Almighty. I am deeply grateful to my guide Dr. Anu Bansal. To work with her has been a real pleasure to me, with heaps of fun and excitement. She has been a steady influence throughout my postgraduate career; she always oriented and supported me with promptness and care, and have always been patient and encouraging in times of new ideas and difficulties. She encouraged me to not only grow as a student but also as an independent thinker. I am not sure many post graduate students are given the opportunity to develop their own individuality and self-sufficiency by being allowed to work with such independence. I admire her ability to balance research interests and personal pursuits. Above all, she made me feel a friend, which I appreciate from my heart.

I would like to thank my head of institution Dr Harshita Sharma, for her support and always made sure students were prepared for whatever the next step in their journeys may be. I am especially indebted to my teachers for their faith in me and allowing me to be as ambitious as I wanted. It was under their watchful eye that I gained so much drive and an ability to tackle challenges head on. I would like to thank Dr. Madhu Thotapillil, sports medicine consultant for the Chennai super king-champions league, and also to my ex colleagues who introduced me to the world of sports .I would also like to acknowledge my batch mates for their love , support , endless humors and laughter by which I learnt to cope up during my tough time in this thesis. I can't imagine my current position without the love and support from my family. I thank my parents, Mr Bhaskar Patel and Mrs. Arti Patel, for striving hard to provide a good education for me and my sibling. I always fall short of words and felt impossible to describe their support in words. If I have to mention one thing about them, among many, then I would proudly mention that my parents are very simple and they taught me how to lead a simple life. Last but not the least I would like to remember and thank my paternal grandfather and grandmother for their prayers. I strongly believe that their prayers played very important role in my life. They are not here with me anymore but their prayers and blessing will always guide me throughout my journey.

References

- Shin KM (2011) Partial thickness rotator cuff tears. Korean J pain 24(2): 69-73.

- Nicholas JA, Hershman EB (1990) The upper extremity in sports medicine. American Journal of Sports Medicine.

- Kibler WB (1998) Shoulder rehabilitation: principles and practice. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30(4 Suppl): S40-S50.

- Chmielewski TL, Myer GD, Kauffman D, Tillman SM (2006) Plyometric exercise in the rehabilitation of athletes: physiological responses and clinical application. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 36(5): 308-319.

- Roberta Ainsworth, Jeremy S Lewis (2007) Exercise therapy for the conservative management of full thickness tears of the rotator cuff: a systemic review. Br J Sports Med 41(4): 200-210.

- 6. Tanaka M, Itoi E, Sato K, Hamada J, Hitachi S, et al. (2010) Factors related to successful outcomes of conservative management of the rotator cuff tears. Ups J Med Sci 115(3): 193-200.

- Paula Dohoney, Chormiak JA, Lemire D, Abadie BR, Kovacs C, et al. (2002) Prediction of one repetition maximum strength from 4-6RM and 7-10RM submaximal strength test in healthy young adult males. Journal of exercise physiology 5(3): 54-59.

- Tsetseli M, Mailliou V, Zetzot E, Maria M, Antonis K, et al. (2010) The effect of coordination training program on the development of tennis service technique. Journal of biology of exercise 6(1): 29-36.

- Pezzullo DJ, Karas S, Irrgang JJ (1995) Functional plyometric exercises for the throwing athlete. J Athl Train 30(1): 22-26.

- Vossen JE, Kramer JE, Burke DG, Vossen DP (2000) Comparison of dynamic push-up training and plyometric push-up training on upper body power and strength. Journal of strength and conditioning Research 14(3): 248-253.

- Kugler A, Kruger-Franke M, Reininger S, Trouillier HH, Rosemeyer B, et al. (1996) Muscular imbalance and shoulder pain in volleyball attackers. Br J Sports Med 30(3): 256-259.

- Chimera NJ, Swanik KA, Swanik CB, Straub SJ (2004) Effects of plyometric training on muscle-activation strategies and performance in female athletes. J Athl Train 39(1): 24-31.

- Roopchand-Martin S, Lue-Chin P (2010) Plyometric training improves power and agility in jamaicas national netball team. West Indian Med J 59(2): 182-187.

- Carter AB, Kaminski TW, Douex AT, Knight CA, Richards JG, et al. (2007) Effects of high volume upper extremity plyometric training on throwing velocity and functional strength ratios of the shoulder rotators in collegiate baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 21(1): 208-215.

- McCann PD, Wootten ME, Kadaba MP, Bigliani LU (1993) A kinematic and electromyographic study of shoulder rehabilitation exercises. Clin Orthop Relat Res 288: 179-188.

- Oliver M, Cornin JB, McNair PJ (2004) Muscle stiffness and injury effects of whole body vibration. Physical therapy in sport 5(2): 68-74.

- Chang WK (2004) Shoulder impingement syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 15(2): 493-510.

- Courtney Peters, Steven Z George (2001) Outcomes following plyometric rehabilitation for the young throwing athlete. Physiotherapy theory and practice, Informa, UK, pp. 1-14.

- Kelly BT, Williams RJ, Cordasco FA, Backus SI, Otis JC, et al. (2005) Differential patterns of muscle activation in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 14(2): 165171.

- Heiderscheit BC, McLean KP, Davies GJ (1996) The effects of isokinetic versus plyometric training on the shoulder internal rotators. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 23(2): 125-33.

- Chad Fortun The effects of plyometric training on the shoulder internal rotators. Fortun, pp. 63-75.

- Moore LH, Tankovich MJ, Riemann BL, Davies GJ (2012) kinetic analysis of four plyometric push up vairations. Int J Exerc Sci 5(4): 334-343.

- Brumitt J, Meira EP, En Gilpin H, Brunette M (2011) Comprehensive strength training program for a recreational senior golfer 11 months after a rotator cuff repair. Int J Sports Phys Ther 6(4): 343-356.

- Ebben WP, Jensen RL, Blackard DO (2000) Electromygraphic and kinetic analysis of complex training variables. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 14(4): 451-456.

- Ebben WP, Watts PB (1998) A review of combined weight training and plyometric training modes; complex training. Strength Conditioning Journal 20(5): 18-27.

- Ebben WP (2002) Complex training: A brief review. J Sports Sci Med 1(2): 42-46.

- Rajamohan G, Kangasabai P (2010) Effects of complex and contrast resistance and plyometric training on selected strength and power parameters. Journal of Experimental Sciences 1(12): 1-12.

- Nicholas TR (1994) A biomechanical perspective on spinal mechanisms of coordinated muscular action: An architecture principle. Acta Anat 151(1): 1-13.

- Sauers EL, Dykstra DL, Bay RC, Bliven KH, Snyder AR (2011) Upper extremity injury history, current pain rating and health related quality of life in female softball players. Journal of Sports Rehabilitation 20(1): 100-114.

- Ogata S, Uthoff HK (1990) Acromial enthesopathy and rotator cuff tear. A radiologic and histologic postmoterm investigation of the coracoaromial arch. Clin Orthop Relat Res, pp. 39-48.

- Sher JS, Uribe JW, Posada A, Murphy BJ, Zaltkin MB et al. (1995) Abnormal findings on the magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77(1): 10-5.

- Lohr JF, Uthoff HK (2007) Epidemiology and pathophysiology of rotator cuff tears. Orthopade 36(9): 788-795.

- Fukuda H (2000) partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a modern view on codmans classic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg pp. 163-168.

- Ozaki J, Fujimoto S, Nagawaka Y, Tamai S (1988) Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 70(8): 1224-1230.

- Nho SJ, Yadav H, Shinde MK (2008) Rotator cuff degeneration: etiology and pathogenesis. Am J Sports Med 36(5): 987-993.

- Chalmers G (2002) Do golgi tendon organ really inhibit muscle activity at high force level to save muscle from injury and adapt strength training? Sports Biomech 1(2): 239-249.

- Kevin EW, Meister K, Andrews JR (2002) Current concept in the rehabilitation of the overhead throwing athlete. Am J Sports Med 30(1): 136-151.

- Dixon D, Johnson M, Mcqueen M (2008) The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire can measure the impairment, activity limitations and participation restriction constructs from the international classification of functioning, disability and health. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, DOI: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-114.

- Beaton, Hudak P, Davis AM, Mcconnell S (2001) Disabilities of the arm shoulder and hand questionnaire. Journal of Hand Therapy 6(4): 128146.

- Bot SD, Terwee CB, van der Windt DA, Bouter LM, Dekker J, et al. (2004) Clinimetric evaluation of shoulder disability questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis 63(4): 335-341.

- Turchin DC (1998) Disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

- Wilk K, Voight ML, Keirns MA, Gambetta V, Andrews JR, et al. (1993) stretch-shortening drills for the upper extremity: theory and clinical application. Journal of Sports and Physical Therapy 17(5): 225-239.

© 2018 Ritika Patel, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)