- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography

Expanding Information on the Prey Items and Hunting Tactics of the Eastern Tropical Pacific Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) Ecotype

Christian D Ortega-Ortiz1*, Camila Lazcano-Pacheco2, Myriam Llamas-González2, Raziel Meza-Yáñez2, Silvia Ruano-Cobian1, Diana G López-Luna1 and Marco A Liñán-Cabello1

1Faculty of Marine Sciences, University of Colima, Mexico

2South Coast University Center, University of Guadalajara, Mexico

*Corresponding author: Christian D Ortega-Ortiz, Faculty of Marine Sciences, University of Colima, Km 20 Carr. Manzanillo-Barra de Navidad, Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico

Submission: August 22, 2023;Published: September 06, 2023

ISSN 2578-031X Volume6 Issue2

Abstract

The killer whale (Orcinus orca) distributed in the Eastern Tropical Pacific may represent a new ecotype with distinct morphological and ecological characteristics, among them, a generalist feeding habit that includes marine mammals, sea turtles, elasmobranchs, and bony fishes. Some of these prey species have been previously reported for the Mexican Central Pacific; however, three additional prey species have been recorded in recent years. A whale shark (Rhincodon typus), a spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris), and black sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizii) were preyed by killer whale individuals presenting the morphological characteristics of the Eastern Tropical Pacific ecotype; some of them had been previously reported as potential prey. This represents an expansion of the killer whale prey list and shows that a very generalist feeding habit is one of the main characteristics of this killer whale ecotype, which has displayed surprising hunting tactics that need to be investigated further to obtain sufficient information to ensure its conservation.

Keywords:Killer whales; Ecotype; Eastern tropical pacific; Prey items

Abbreviations: KW: Killer Whale; ENP: Eastern North Pacific; ETP: Eastern Tropical Pacific; MCP: Mexican Central Pacific

Introduction

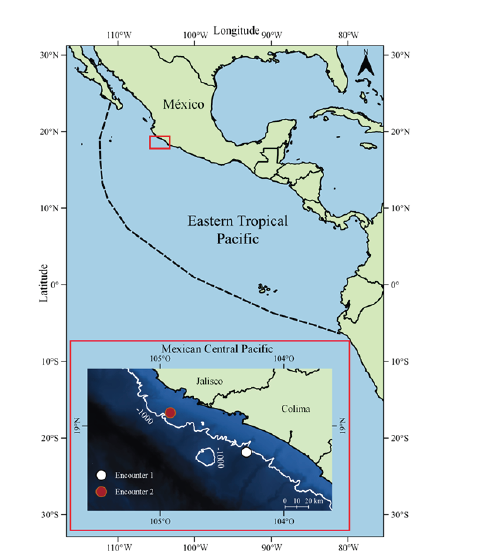

The killer whale (KW, Orcinus orca) is the most cosmopolitan species among cetaceans [1,2]. A classification into ten KW ecotypes worldwide [3-6] has been suggested, based on biological [7-10] and ecological aspects [8,11-13]. Three KW ecotypes have been described in the region of Eastern North Pacific (ENP), based on distribution patterns, behavior, morphology, acoustics, and feeding preferences: Fish-eating “residents”, mammal-eating “transients”, and large mammal/fish-eating “offshore” KWs [7,8,10,12,14]. Until a few decades ago, no ecotype had been recognized in the Eastern Tropical Pacific (ETP, an area encompassing from the southern Baja California Peninsula, Mexico, to northern Peru, including Galapagos Islands) [15] (Figure 1). However, recently Vargas-Bravo et al. [16] proposed recently that KW inhabiting the Mexican Central Pacific (MCP) (Figure 1) could be part of a new ecotype, the Eastern Tropical Pacific or ETP ecotype. The KW observed in this area demonstrated some variations in seasonal-spatial distribution patterns, group size structure, morphology, behavior, and trophic niche, compared with other ecotypes [15]. In particular, information on the trophic niche of these KW suggests generalist behavior, as they preyed on whales, dolphins, sea turtles, and bony fishes [16].

Figure 1:Encounter sites in the Mexican Central Pacific, where killer whales with similarities to the Eastern Tropical Pacific ecotype were observed hunting recently (March 2021).

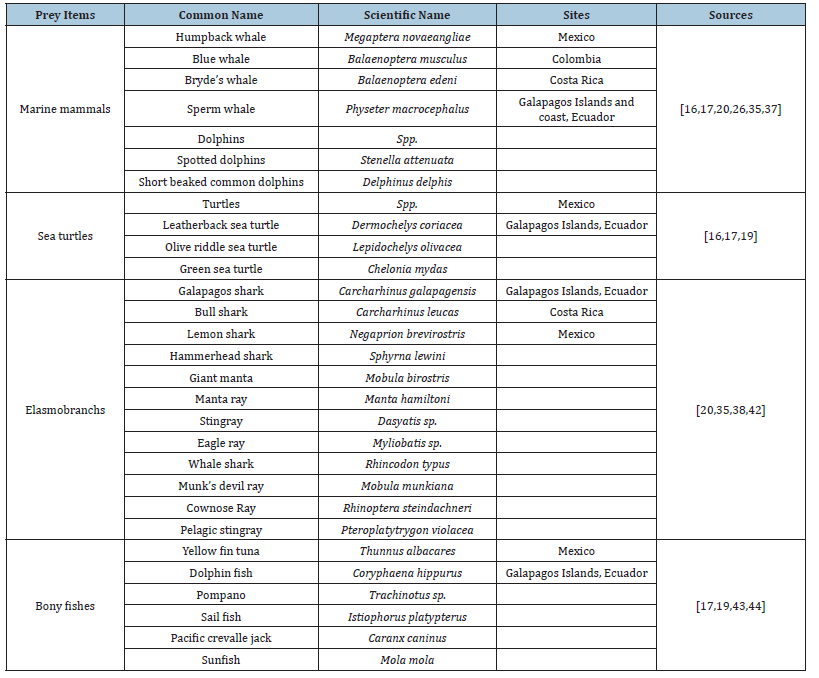

The distribution range of this new trophic generalist KW ecotype is unknown and needs to be investigated with tools such as photo-identification or satellite tracking of individuals; however, considering research on KW groups from other regions within the ETP, that have also been recognized as generalist predators, the range of this KW ecotype could extend from Mexico to Peruvian waters [17]. Previous studies show that KW distributed in ETP waters have preyed on marine mammals, as well as sea turtles, elasmobranchs (sharks and manta rays), and bony fishes [16-21]. Table 1 shows the wide variety of species that KW have preyed in the ETP region; in this way, the ETP KW ecotype feeding habit differs widely from the feeding activity reported for the trophic specialist ecotypes found in the rest of the ENP [12,15,22,23].

Table 1:Several prey items reported for killer whales (Orcinus orca) from the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

The aim of the present document is to report on the prey items and hunting tactics of the ETP KW ecotype [16] through the documentation of a couple of recent predation events occurred in the MCP, which highlight the wide range of prey species exploited by this top predator [24,25].

Results

1st Killer whale predatory encounter

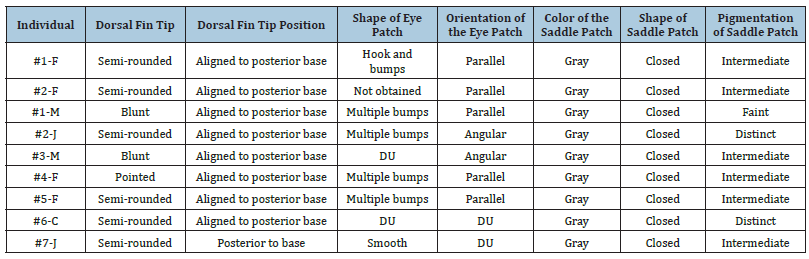

The first encounter occurred 24.3km off the coast of Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico, at a depth of 1,494m, on March 28, 2021 (Figure 1). Crew on a sport fishing trip aboard the Mahi-Mahi observed two adult KW females moving in a circle; when the boat approached the KW, the crew observed that they were attacking a whale shark (Rhincodon typus). This was a juvenile approximately 3-4m long, which was repeatedly struck in the ventral region by both KW, until it was killed and subsequently consumed by both. This behavior was observed through a video obtained with an underwater camera (Figure 2). Afterwards, the KW approached the boat and were photographed as they emerged from the water. These photographs were used to analyze their morphological characteristics; Table 2 presents these morphological features of the two KW females. They both showed a dorsal fin tip aligned to the posterior base, of semi-rounded type, with parallel orientation of the hook-and-bump type eye patch, and a closed saddle patch with intermediate gray pigmentation, matching the description proposed for the ETP KW ecotype [16].

Figure 2:Juvenile whale shark (Rhincodon typus) preyed upon by a pair of female killer whales in the Mexican Central Pacific, March 28, 2021. The image above shows the pair harassing the whale shark on the water surface. The following sequence of photos is from an underwater video, showing the alternation of killer whale individuals striking the ventral region of the whale shark.

Table 2:Morphological features of killer whales (Orcinus orca) observed recently in the Mexican Central Pacific, with similarities to the Eastern Tropical Pacific ecotype. 1st and 2nd rows belong to KW from the March 28, 2021, encounter, the other rows are individuals observed during the March 31, 2021 encounter. M: Male, F: Female, J: Juvenile, C: Calf and DU: Data unknown

2nd killer whale predatory encounter

Three days later, on March 31, 2021, the sport fishing boat Manglito reported a group of approximately 10KW (two adult males, four adult females, two juveniles, and two calves) involved in predatory activity on a dolphin at site 18.2km off the bay of Barra de Navidad, Jalisco, Mexico at a depth of 758m. Our research group was conducting a coastal monitoring program on humpback whales, and we were able to go to the site to record the encounter.

Upon arrival at the site, we observed the KW group harassing a spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris). It appeared to be a mature male (by the inclination of its dorsal fin towards the forepart of the body and by its ventral protrusion) swimming in a tight circle of only about ten meters in diameter because it was “cornered” by the KW. During the interaction, the dolphin emerged at the water surface to breathe and was hit by the KW. We also observed that the KW broke the water surface by hitting it with their flukes and by the acceleration of their bodies while they were chasing the dolphin. The surface activity decreased a few minutes later and we introduced an underwater camera with which we could visualize all the KW working as a team to dismember and consume the dolphin (Figure 3). One of the calves was later observed holding a dolphin organ in its jaws, possibly the kidney, given its characteristics (multilobed) and consistency [26] (Figure 4). At the same time, a significant number of seabirds (gulls, magnificent frigatebirds, among others) consumed the body remains of the dolphin that began to appear on the water surface.

Figure 3:Killer whales working as a team to dismember and consume a spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris) in the Mexican Central Pacific, March 31, 2021.

Figure 4:Calf killer whale holding a spinner dolphin organ in its jaws, possibly a kidney (multilobed), Mexican Central Pacific, March 31, 2021.

After the attack on the spinner dolphin, the KW group began to sail west, and encountered an olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea). This turtle was pushed by one juvenile KW using the forepart of its body, but was not preyed on, in spite of this species having been reported as an ETP ecotype KW prey [17]. However, a few nautical miles later the group of predators interacted with a black sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizii); which was preyed upon in a very peculiar way. The hunting tactic consisted of the following:

An adult female stealthily positioned herself underneath the turtle and held it in her jaws by the rear flippers to forcefully submerge it; a few meters down it released it and executed a powerful bite that caused lethal wounds to body parts including the turtle’s shell. The KW then emerged at the water surface of the water, with the turtle clamped in its jaws. The turtle showed conspicuous wounds from which blood gushed out and spread around it; the female submerged again, without releasing the turtle (Figure 5). Afterwards, only the turtle remains, such as parts of internal organs, could be observed; these began to appear on to the water surface accompanied by a grease-like odor. A few minutes later, the attacking female and one male KW emerged to breathe very close to the site; we assumed that both consumed the turtle. The site was swarming with seabirds competing with each other to ingest the remains of the turtle. This hunting tactic was repeated three times (during one attack the male headed the hunt), preying only on black sea turtles, in an area with a diameter of approximately 3 to 6km. The encounter ended at 17:56h, at a distance of approximately 28km from the bay of Barra de Navidad [27-30].

Figure 5:Female killer whale holding a black sea turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizii) in its jaws, before submerging it again to prey on it, Mexican Central Pacific, March 31, 2021. Note the scattering of blood in the middle of the photograph due to the fatal wounds.

Similar to encounter 1, KW individuals were photographed when they emerged from the water to use the photo-identification technique and to analyze their morphological characteristics. However, the photographs obtained were of sufficient quality for this task for only seven of the individuals. These individuals were different from the KW females observed 3 days earlier approximately 50km further south, based on the shape, markings, and scars of the dorsal fin, saddle, and eye patch [9]. Nevertheless, these individuals also displayed morphological features typical of the ETP ecotype [16]; i.e., a dorsal fin tip aligned to the posterior base and mainly of semi-rounded type, the parallel orientation of the multiple-bumps type eye patch, and a closed saddle patch with intermediate gray pigmentation (Table 2).

This suggests that despite the short time difference between the encounters, these were different groups, or that they probably belonged to one group with a very wide distribution and not all individuals in the group were observed together during each encounter.

Discussion

KW are ubiquitous marine predators; they are highly specialized and efficient hunters, capable of adjusting the type of prey that they consume. This prey selection may have critical implications for prey population dynamics. However, there are many unknowns regarding the consumption preferences of certain species [31]. The present document reports/confirms three prey species that were preyed upon by ETP KW: i) a whale shark, ii) a spinner dolphin, and iii) a black sea turtle. It should be noted that the presence of whale sharks in the MCP region is not common, so this would not be expected to be a potential prey species for KW that inhabit this region. There have been two reports of predation on whale sharks in the northwestern Gulf of California, particularly in Bahía de Los Ángeles [21,25], and it is possible that KW involved in such encounters belonged to another ecotype. Unfortunately, these reports have not been published and it is not possible to reanalyze the information (e.g., morphological characteristics of the KW individuals involved) to find out if these KW resembled those of the ETP.

Vargas-Bravo et al. [16] reported a potential KW predatory event on a spinner dolphin that was found stranded on a Colima beach in May 2015. The dolphin presented fresh rake-like wounds (equidistance between the parallel lines made by the teeth on the genital area [26]); however, an interaction between KW and the spinner dolphin was not observed. It is therefore also possible that this dolphin could have been attacked by another predator, such as false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens), which are also distributed in the area and use the region’s habitat for ecological purposes [27].

Our KW hunting event on black sea turtles represents a first record for the ETP ecotype. The notable preference for preying on black sea turtle seen during this encounter has not been previously reported. One hypothesis may be that the black sea turtle biomass, larger size, and weight (compared with olive ridley turtles [28]) would provide more nutritional resources for predators; or, the fact that they lay a greater number of eggs (>65) per nest, as well as greater number of nests (~7) per breeding season (also compared with olive ridley turtles [29]). From a physiological viewpoint, this could favor the energy stores that a predator such as a KW could take advantage of. However, this is an idea that needs to be investigated in depth. The present study contributes to expand the list of prey species and shows that the main characteristic of this ecotype, in addition to its morphology, is a generalist predatory habit. A similar generalist predatory behavior has been suggested for KW from other ocean basins such as the Caribbean [32], New Zealand [33], the Galapagos Islands [34], and the Southwest Indian Ocean [35], where the existence of KW individual ecotypes remains unclear [16]. It is likely that these individuals also represent a different ecotype from those recognized worldwide

However, more information is needed to complete the “puzzle” regarding the biology/ecology of these tropical KW of the ETP and studies such as photo-identification or satellite tracking on individuals would contribute to establish the potential limits of their distribution. Genetics and acoustic studies that would also aid to differentiate this ecotype to ensure measures that allow an adequate management for their conservation [36-40].

Conclusion

The KWs distributed in regions of the ETP show different morphological characteristics and a generalist feeding habit compared to other ecotypes. This paper confirms two species (whale shark and spinner dolphin) as prey for this killer whale ecotype, and also reports a new prey (black sea turtle) for the ETP region. These KW employed hunting techniques (striking, diving and dismemberment) that had already been reported as part of their predatory strategy but are still surprising [41-43].

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Iván Livas, captain of the vessel “Mahi- Mahi” for the information provided for the first encounter; Alan López captain of the vessel “Manglito” for the calling at sea to obtain the information for the second encounter; to the Faculty of Marine Sciences of the University of Colima for the logistical support, to the marina Las Hadas for their support in safeguarding our research vessel, and to the Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT), for the research permit SGPA/ DGVS/08928/21.

References

- Bryun PJN, Tosh, CA, Terauds A (2012) Killer whale ecotypes: Is there a global model? Biological Reviews 88(1): 62-80.

- Heyning JE, Dahlheim ME (1988) Orcinus orca. Mammalian Species 304: 1-9.

- Barrett-Lennard L (2011) Killer whale evolution: Populations, ecotypes, species, Oh my! In: Pitman RL (Ed.), Killer whale: The top, top predator. Whalewatcher 40: 48-53.

- Foote A (2011) North Atlantic killer whales. In Pitman RL (Ed.), Killer whale: The top, top predator. Whalewatcher 40: 303-332.

- Pitman R, Ensor P (2003) Three forms of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Antarctic waters. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 5(2): 131-139.

- Pitman RL, Durban JW, Greenfelder M, Guinet C, Jorgensen M, et al. (2011) Observations of a distinctive morphotype of killer whale (Orcinus orca), type D, from subantarctic waters. Polar Biology 34: 303-306.

- Baird RW, Stacey, P (1988) Variation in saddle patch pigmentation in populations of killer whales (Orcinus orca) from British Columbia, Alaska, and Washington State. Canadian Journal of Zoology 66(11): 2582-2585.

- Baird RW, Whitehead H (2000) Social organization of mammal-eating killer whales: Group stability and dispersal patterns. Canadian Journal of Zoology 78(12): 2096-2105.

- Bigg MA, Olesiuk PF, Ellis GM, Ford JKB, Balcomb III KC (1990) Social organization and genealogy of resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) in the coastal waters of British Columbia and Washington State. In: Hammond, PS, Mizroch SA, Donovan GP (Eds.), Individual recognition of cetaceans: Use of photo-identification and other techniques to estimate population parameters. Reports of the International Whaling Commission. Special Issue 12: 386-406.

- Foote AD, Nystuen JA (2008) Variation in call pitch among killer whale ecotypes. Journal of Acoustic Society of America 123(3): 1747-1752.

- Barrett-Lennard LG, Matkin CO, Durban JW, Saulitis EL, Ellifrit D (2011) Predation on gray whales and prolonged feeding on submerged carcasses by transient killer whales at Unimak Island, Alaska. Marine Ecology Progress Series 421: 229-241.

- Ford JKB, Ellis G, Barrett-Lennard L, Morton AB, Palm RS, et al. (1998) Dietary specialization in two sympatric populations of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in coastal british Columbia and adjacent waters. Canadian Journal of Zoology 76(8): 1456-1471.

- Ford JKB, Ellis GM, Matkin CO, Wetklo MH, Barrett-Lennard LG, et al. (2011) Shark predation and tooth wear in a population of northeastern Pacific killer whales. Aquatic Biology 11: 213-224.

- Dahlheim ME, Schulman-Janiger A, Black N, Ternullo R, Ellifrit D, et al. (2008) Eastern temperate North Pacific offshore killer whales (Orcinus orca): Occurrence, movements, and insights into feeding ecology. Marine Mammal Science 24(3): 719-729.

- Olson P, Gerrodette T (2008) Killer whales of the Eastern Tropical Pacific: A catalog of photo-identified individuals. NOAA Technical Memmorandum NMFS; NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-428, pp. 1-126.

- Vargas BMH, Elorriaga VFR, Olivos OA, Morales GB, Liñán CMA, et al. (2020) Ecological aspects of killer whales from the Mexican Central Pacific coast: Revealing a new ecotype in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Marine Mammal Science 37(2): 674-689.

- Pacheco AS, Castro C, Carnero HR, Villagra D, Pinilla S, et al. (2019) Sightings of an adult male killer whale match. Aquatic Mammals 45(3): 320-326.

- Guerrero-Ruiz ME (1997) Current Knowledge of the Orca Orcinus orca (Linnaeus 1758) in the Gulf of California, Mexico [Current knowledge of the orca Orcinus orca (Linnaeus 1758) in the Gulf of California, Mexico] (Bachelor's thesis). Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, La Paz, Mé

- Sánchez-Díaz VM, Meráz J (2001) Record of predation on Dermochelys coriacea, on the coast of Oaxaca by Orcinus orca. Science and Sea 5: 51-54.

- Guerrero-Ruiz ME, Urbán J, Gendron D, Rodríguez ME (2007) Prey items of killer whales in the Mexican Pacific. Paper SC/59/SM14 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee. USA.

- Testino JP, Petit A, Alcorta B, Pacheco AS, Silva S, et al. (2018) Killer whale (Orcinus orca) occurrence and interactions with marine mammals off Peru. Pacific Science 73(2): 261-273.

- Herman DP, Burrows DG, Wade PR, Durban JW, Matkin CO, et al. (2005) Feeding ecology of eastern North Pacific killer whales Orcinus orca from fatty acid, stable isotope, and organochlorine analyses of blubber biopsies. Marine Ecology Progress Series 302: 275-291.

- Krahn MM, Hanson MB, Baird RW, Boyer RH, Burrows DG, et al. (2007) Persistent organic pollutants and stable isotopes in Biopsy samples (2004/2006) from Southern Resident killer whales. Marine Pollution Bulletin 54(12): 1903-1911.

- O’Sullivan JB, Mitchell T (2000) A fatal attack on a whale shark Rhincodon typus, by killer whales Orcinus orca off Bahia de Los Angeles, Baja California. In Abstract: American Elasmobranch Society Whale Shark Symposium.

- Sánchez-Fabila G, Contreras-Villanueva MD, Moreno CR (2016) Plastination and anatomical description of the liver, spleen, stomach and kidneys of the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). International Journal of Morphology 34(2): 644-652.

- Steiger GH, Calambokidis J, Straley JM, Herman LM, Cerchio S (2008) Geographic variation in killer whale attacks on humpback whales in the North Pacific: Implications for predation pressure. Endangered Species Research 4: 247-256.

- Lazcano‐Pacheco C, Castillo‐Sánchez AJ, Ortega‐Ortiz CD, Martínez‐Serrano I, Villegas‐Zurita F, et al. (2023) Ecological aspects of false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) from Mexican Pacific and Southern California waters. Marine Mammal Science, p. 1-12.

- Eckert KL, Bjorndal KA, Abreu-Grobois FA, Donnelly M (Eds.), (2000) Research and management techniques for the conservation of sea turtles. IUCN/SSC Sea Turtle Specialist Group Publication No. 4.

- Mota-Rodríguez C, Riosmena-Rodríguez R, Santisteban-Espíndola I, Camacho-Romero FJ, Lara-Uc MM (2015) Brown or black turtle of the Eastern Pacific. Biome 29(3): 63-67.

- Ferguson SH, Kingsley MCS, Higdon JW (2012) Killer whale (Orcinus orca) predation in a multi-prey system. Population Ecology 54(1): 31-41.

- Bolaños-Jiménez J, Mignucci-Giannoni AA, Blumenthal J, Bogomolni A, Casas JJ, et al. (2014) Distribution, feeding habits and morphology of killer whales Orcinus orca in the Caribbean Sea. Mammal Review 44(3-4): 177-189.

- Visser I, Mäkeläinen P (2000) Variation in eye-patch shape of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in New Zealand waters. Marine Mammal Science 16(2): 459-469.

- Denkinger J, Alarcon D, Espinosa B, Fowler L, Manning C, et al. (2020) Social structure of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in a variable low-latitude environment, the Galápagos Archipelago. Marine Mammal Science 36(3): 774-785.

- Terrapon M, Kiszka JJ, Wagner J (2021) Observations of killer whale (Orcinus orca) feeding behavior in the tropical waters of the Northern Mozambique Channel Island of Mayotte, Southwest Indian Ocean. Aquatic Mammals 47(2): 196-205.

- Alava J, Merlen G (2009) Video-documentation of a killer whale (Orcinus orca) predatory attack on a giant manta (Manta birostris) in the Galápagos Islands. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 7(1-2): 81-84.

- Cosentino M, Oria N (2021) Insights into the foraging behaviour of an understudied orca Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 16(1): 51-53.

- Perryman WL, Foster TC (1980) Preliminary report on predation by small whales, mainly the false killer whale Pseudorca crassidens, on dolphins (Stenella spp. and Delphinus delphis) in the eastern tropical Pacific (Administrative Report LJ-80-05). National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

- Watson L (1981) Sea guide to whales of the world. Hutchinson Publishers, London, pp. 1-302.

- Fertl D, Acevedo-Gutierrez A, Darby FL (1996) A report of killer whales (Orcinus orca) feeding on a carcharhinid shark in Costa Rica. Marine Mammal Science 12(4): 606-611.

- Sorisio LS, Maddalena A, Visser IN (2006) Interaction between killer whales (Orcinus orca) and hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna sp.) in Galápagos waters. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 5(1): 69-71.

- Higuera-Rivas JE, Hoyos-Padilla EM, Elorriaga-Verplancken FR, Rosales-Nanduca H, Rosenthal R, et al. (2023) Orcas (Orcinus orca) use different strategies to Prey on rays in the Gulf of California. Aquatic Mammals 49(1): 7-18.

- Merlen G (1999) The orca in Galapagos: 135 sightings. Noticias de Galápagos 60: 2-8.

- Vázquez-Ruiz KM (2004) Spatial-temporal distribution of the killer whale (Orcinus Orca) 'CETACEA', Feeding behavior and identification of individuals in Bahía de Banderas Nayarit-Jalisco, during the period between the years 1982-2003. Bachelor Thesis, Technological Institute of Bahía de Banderas, pp. 1-61.

- Bryun PJN, Tosh, CA, Terauds A (2012) Killer whale ecotypes: Is there a global model? Biological Reviews 88(1): 62-80.

- Heyning JE, Dahlheim ME (1988) Orcinus orca. Mammalian Species 304: 1-9.

- Barrett-Lennard L (2011) Killer whale evolution: Populations, ecotypes, species, Oh my! In: Pitman RL (Ed.), Killer whale: The top, top predator. Whalewatcher 40: 48-53.

- Foote A (2011) North Atlantic killer whales. In Pitman RL (Ed.), Killer whale: The top, top predator. Whalewatcher 40: 303-332.

- Pitman R, Ensor P (2003) Three forms of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Antarctic waters. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 5(2): 131-139.

- Pitman RL, Durban JW, Greenfelder M, Guinet C, Jorgensen M, et al. (2011) Observations of a distinctive morphotype of killer whale (Orcinus orca), type D, from subantarctic waters. Polar Biology 34: 303-306.

- Baird RW, Stacey, P (1988) Variation in saddle patch pigmentation in populations of killer whales (Orcinus orca) from British Columbia, Alaska, and Washington State. Canadian Journal of Zoology 66(11): 2582-2585.

- Baird RW, Whitehead H (2000) Social organization of mammal-eating killer whales: Group stability and dispersal patterns. Canadian Journal of Zoology 78(12): 2096-2105.

- Bigg MA, Olesiuk PF, Ellis GM, Ford JKB, Balcomb III KC (1990) Social organization and genealogy of resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) in the coastal waters of British Columbia and Washington State. In: Hammond, PS, Mizroch SA, Donovan GP (Eds.), Individual recognition of cetaceans: Use of photo-identification and other techniques to estimate population parameters. Reports of the International Whaling Commission. Special Issue 12: 386-406.

- Foote AD, Nystuen JA (2008) Variation in call pitch among killer whale ecotypes. Journal of Acoustic Society of America 123(3): 1747-1752.

- Barrett-Lennard LG, Matkin CO, Durban JW, Saulitis EL, Ellifrit D (2011) Predation on gray whales and prolonged feeding on submerged carcasses by transient killer whales at Unimak Island, Alaska. Marine Ecology Progress Series 421: 229-241.

- Ford JKB, Ellis G, Barrett-Lennard L, Morton AB, Palm RS, et al. (1998) Dietary specialization in two sympatric populations of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in coastal british Columbia and adjacent waters. Canadian Journal of Zoology 76(8): 1456-1471.

- Ford JKB, Ellis GM, Matkin CO, Wetklo MH, Barrett-Lennard LG, et al. (2011) Shark predation and tooth wear in a population of northeastern Pacific killer whales. Aquatic Biology 11: 213-224.

- Dahlheim ME, Schulman-Janiger A, Black N, Ternullo R, Ellifrit D, et al. (2008) Eastern temperate North Pacific offshore killer whales (Orcinus orca): Occurrence, movements, and insights into feeding ecology. Marine Mammal Science 24(3): 719-729.

- Olson P, Gerrodette T (2008) Killer whales of the Eastern Tropical Pacific: A catalog of photo-identified individuals. NOAA Technical Memmorandum NMFS; NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-428, pp. 1-126.

- Vargas BMH, Elorriaga VFR, Olivos OA, Morales GB, Liñán CMA, et al. (2020) Ecological aspects of killer whales from the Mexican Central Pacific coast: Revealing a new ecotype in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Marine Mammal Science 37(2): 674-689.

- Pacheco AS, Castro C, Carnero HR, Villagra D, Pinilla S, et al. (2019) Sightings of an adult male killer whale match. Aquatic Mammals 45(3): 320-326.

- Guerrero-Ruiz ME (1997) Current Knowledge of the Orca Orcinus orca (Linnaeus 1758) in the Gulf of California, Mexico [Current knowledge of the orca Orcinus orca (Linnaeus 1758) in the Gulf of California, Mexico] (Bachelor's thesis). Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, La Paz, Mé

- Sánchez-Díaz VM, Meráz J (2001) Record of predation on Dermochelys coriacea, on the coast of Oaxaca by Orcinus orca. Science and Sea 5: 51-54.

- Guerrero-Ruiz ME, Urbán J, Gendron D, Rodríguez ME (2007) Prey items of killer whales in the Mexican Pacific. Paper SC/59/SM14 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee. USA.

- Testino JP, Petit A, Alcorta B, Pacheco AS, Silva S, et al. (2018) Killer whale (Orcinus orca) occurrence and interactions with marine mammals off Peru. Pacific Science 73(2): 261-273.

- Herman DP, Burrows DG, Wade PR, Durban JW, Matkin CO, et al. (2005) Feeding ecology of eastern North Pacific killer whales Orcinus orca from fatty acid, stable isotope, and organochlorine analyses of blubber biopsies. Marine Ecology Progress Series 302: 275-291.

- Krahn MM, Hanson MB, Baird RW, Boyer RH, Burrows DG, et al. (2007) Persistent organic pollutants and stable isotopes in Biopsy samples (2004/2006) from Southern Resident killer whales. Marine Pollution Bulletin 54(12): 1903-1911.

- O’Sullivan JB, Mitchell T (2000) A fatal attack on a whale shark Rhincodon typus, by killer whales Orcinus orca off Bahia de Los Angeles, Baja California. In Abstract: American Elasmobranch Society Whale Shark Symposium.

- Sánchez-Fabila G, Contreras-Villanueva MD, Moreno CR (2016) Plastination and anatomical description of the liver, spleen, stomach and kidneys of the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). International Journal of Morphology 34(2): 644-652.

- Steiger GH, Calambokidis J, Straley JM, Herman LM, Cerchio S (2008) Geographic variation in killer whale attacks on humpback whales in the North Pacific: Implications for predation pressure. Endangered Species Research 4: 247-256.

- Lazcano‐Pacheco C, Castillo‐Sánchez AJ, Ortega‐Ortiz CD, Martínez‐Serrano I, Villegas‐Zurita F, et al. (2023) Ecological aspects of false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) from Mexican Pacific and Southern California waters. Marine Mammal Science, p. 1-12.

- Eckert KL, Bjorndal KA, Abreu-Grobois FA, Donnelly M (Eds.), (2000) Research and management techniques for the conservation of sea turtles. IUCN/SSC Sea Turtle Specialist Group Publication No. 4.

- Mota-Rodríguez C, Riosmena-Rodríguez R, Santisteban-Espíndola I, Camacho-Romero FJ, Lara-Uc MM (2015) Brown or black turtle of the Eastern Pacific. Biome 29(3): 63-67.

- Ferguson SH, Kingsley MCS, Higdon JW (2012) Killer whale (Orcinus orca) predation in a multi-prey system. Population Ecology 54(1): 31-41.

- Bolaños-Jiménez J, Mignucci-Giannoni AA, Blumenthal J, Bogomolni A, Casas JJ, et al. (2014) Distribution, feeding habits and morphology of killer whales Orcinus orca in the Caribbean Sea. Mammal Review 44(3-4): 177-189.

- Visser I, Mäkeläinen P (2000) Variation in eye-patch shape of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in New Zealand waters. Marine Mammal Science 16(2): 459-469.

- Denkinger J, Alarcon D, Espinosa B, Fowler L, Manning C, et al. (2020) Social structure of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in a variable low-latitude environment, the Galápagos Archipelago. Marine Mammal Science 36(3): 774-785.

- Terrapon M, Kiszka JJ, Wagner J (2021) Observations of killer whale (Orcinus orca) feeding behavior in the tropical waters of the Northern Mozambique Channel Island of Mayotte, Southwest Indian Ocean. Aquatic Mammals 47(2): 196-205.

- Alava J, Merlen G (2009) Video-documentation of a killer whale (Orcinus orca) predatory attack on a giant manta (Manta birostris) in the Galápagos Islands. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 7(1-2): 81-84.

- Cosentino M, Oria N (2021) Insights into the foraging behaviour of an understudied orca Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 16(1): 51-53.

- Perryman WL, Foster TC (1980) Preliminary report on predation by small whales, mainly the false killer whale Pseudorca crassidens, on dolphins (Stenella spp. and Delphinus delphis) in the eastern tropical Pacific (Administrative Report LJ-80-05). National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

- Watson L (1981) Sea guide to whales of the world. Hutchinson Publishers, London, pp. 1-302.

- Fertl D, Acevedo-Gutierrez A, Darby FL (1996) A report of killer whales (Orcinus orca) feeding on a carcharhinid shark in Costa Rica. Marine Mammal Science 12(4): 606-611.

- Sorisio LS, Maddalena A, Visser IN (2006) Interaction between killer whales (Orcinus orca) and hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna sp.) in Galápagos waters. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 5(1): 69-71.

- Higuera-Rivas JE, Hoyos-Padilla EM, Elorriaga-Verplancken FR, Rosales-Nanduca H, Rosenthal R, et al. (2023) Orcas (Orcinus orca) use different strategies to Prey on rays in the Gulf of California. Aquatic Mammals 49(1): 7-18.

- Merlen G (1999) The orca in Galapagos: 135 sightings. Noticias de Galápagos 60: 2-8.

- Vázquez-Ruiz KM (2004) Spatial-temporal distribution of the killer whale (Orcinus Orca) 'CETACEA', Feeding behavior and identification of individuals in Bahía de Banderas Nayarit-Jalisco, during the period between the years 1982-2003. Bachelor Thesis, Technological Institute of Bahía de Banderas, pp. 1-61.

© 2023 Christian D Ortega-Ortiz. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)