- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography

A Method To Assess Diver Impact On Hermatypic Corals

Manuel Victoria-Muguira, Horacio Pérez-España, Jorge Brenner and Yuri B Okolodkov*

Instituto de Ciencias Marinas y Pesquerías, Universidad Veracruzana, Mexico

*Corresponding author: Yuri B Okolodkov, Instituto de Ciencias Marinas y Pesquerías, Universidad Veracruzana, Mexico

Submission: May 14, 2021;Published: June 02, 2021

ISSN 2578-031X Volume4 Issue1

Abstract

Based on a case study (the Anegada de Adentro Reef, Veracruz Reef System National Park, southwestern Gulf of Mexico), a method that allows quantifying a negative impact on hermatypic corals is proposed. Two photo transects of 100m length at a constant depth (to avoid differences in a coral community caused by depth) were followed. Both transects had not been previously impacted by divers. One transects is impacted by divers, and the other is without diver impact (control). The impacts were classified according to their origin: (1) by swimming, (2) by Learning on corals or standing on sand, (3) by resuspending sediments, (4) by touching corals, (5) by destroying corals or (6) by collecting organisms. Trimestral observations were performed by taking photographs each meter using a Nikon D800 camera equipped with a Nikkor 16-35mm lens at 1.5m distance from the transect. Every 5m a coral colony was selected, and photographs of a 1x1m quadrant from different angles were taken. A CPCE (Coral Point Count with Excel extensions) program was used to estimate coral coverage. Damage of the photographed colonies was recorded individually as bleaching, partial mortality, presence of diseases or syndromes and growth of algae or other benthic organisms. To identify diver impact, temporal changes along each transect and between them were compared, and possible correlations with a diver impact factor were analyzed.

Keywords: Coral reefs; Gulf of Mexico; Hermatypic corals; Impact assessment; Scuba

Introduction

Despite their great importance and economic and ecosystemic benefits, coral reefs are subjected to human impact, and they are threatened by climate change, overfishing, forest and mangrove destruction, and lack of adequate management by the authorities responsible for their surveillance and conservation. On a world scale, diving in its different modalities is an activity that has experienced a high level of growth during the last decades: each year about 1.5 million people are certified as divers. Diving has generated a negative impact on marine ecosystems [1]. The impact on corals by divers is caused by accidental blows by hand, fins or diving equipment including photographic and video cameras, resulting in stress and fragmentation of coral colonies [2-4]. Divers’ behavior and environmental variables are also important factors [5].

The object of the present study is to quantify contacts between divers and hermatypic (reef-building) corals, resuspension of sediments and fragmentation of corals as indicators to assess the negative impact on coral communities during diving seasons by means of trained lookout divers who would record all the impacts in situ. This could help us to identify the causes to suggest solutions and to make diving sustainable.

Material and Method

Study area

The Veracruzan Reef System National Park is the largest reef system in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico, situated in front of the municipalities of Veracruz, Boca del Río and Alvarado in the State of Veracruz, Mexico. The Anegada de Adentro Reef is an emerged platform reef in the northwestern part of the park, 7.5km from the coast. It is 1.87km in its longest part and 500m in its widest part; its longest axis is directed from NW to SE, and its center is located at 19°13’48’’N and 96°03’46’’W. In total, 35 hermatypic coral species were found in the park [6].

Transects

Two transects were established at 5 to 10m depth: one that receives diver impact and another as a control, without any impact from divers. Both transects were selected as presenting similar conditions in location, site depth, coral coverage and their health, and preferably without a previous visual diver impact. This will allow us to assess if there are differences between the two transects in coral coverage and health originating from SCUBA diving and snorkeling. Each transect was 100m long; plastic labels were attached every 5m along the transects to be surveyed every three months. In addition, the diving site was marked with a buoy.

Diving

For the success of the proposed study, knowledge of the proposal was given to diving service providers in the area, explaining to them the importance of collaboration and training them in obtaining data from visiting divers (users). It was recommended to carry out a 40-minute survey together with a group of visiting divers without warning them previously that their underwater behavior would be assessed. The study encompasses both the high and low diving seasons. A lookout diver keeps enough distance from the diving group to observe each diver and record the amount and the type of impact without interference during the dive. The lookout diver starts with observations from the moment the visiting divers enter the water. In the case of SCUBA divers, the group is divided into three teams: beginners, advanced and professional divers. Furthermore, the divers with a photographic camera are recorded, as well as the final depth and immersion time. Information is recorded on a control sheet to feed into the database (Figure 1). The impacts were classified according to their origin: (1) by swimming, (2) by leaning on corals or standing on sand, (3) by resuspending sediments, (4) by touching corals, (5) by destroying corals or (6) by collecting organisms.

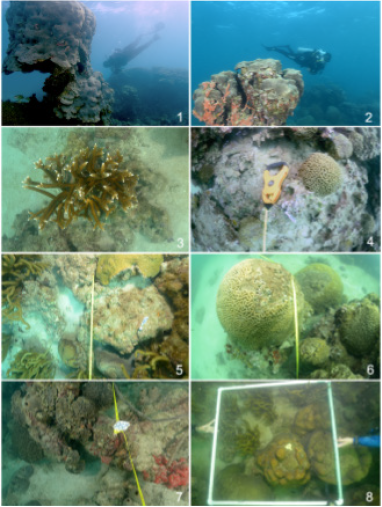

Figure 1:Assessment of diver impact on hermatypic corals along a 100-m transect on the Anegada de Adentro. 1- A surveilling diver in the background (in the foreground is a massive colony of Orbicella faveolata); 2- A lookout diver in the background (in the foreground is an O. faveolata colony covered with sponges); 3- A young colony of Acropora cervicornis, a protected critically endangered species; 4- The end of the transect with dead and living corals; 5- Photo transect above the community of a soft coral Plexaura/Pseudoplexaura, Montastraea cavernosa and a dead coral covered with a macroalgal mat; 6- A photo transect above Colpophyllia natans covered with a macroalgal mat; 7- A photo transect above C. natans and various species of sponges; 8- A 1m2 quadrant above the colonies of Plexaura/Pseudoplexaura, M. cavernosa and C. natans selected to assess the diver impact based on the coral coverage.

Surveillance

It is suggested to perform trimestral photo transects along 100m following a measuring tape and taking a photograph each meter with a Nikon D800 camera equipped with a Nikkor 16-35mm at a 1.5m distance from the bottom where diving activities occur. Every 5m, a selected coral colony located within a 1x1m PVC pipe frame is photographed from various angles for further assessment of changes due to diving activities. To record the initial state of the coral colonies, 20 of them are photographed before diving activities start. Damage of the photographed colonies was recorded individually as bleaching, partial mortality, presence of diseases or syndromes and growth of algae or other benthic organisms.

Information analysis

To assess changes in coral coverage, it is suggested to use the CPCE (Coral Point Count with Excel extensions) program and any that permits determination of coral coverage by photographic images. In each image, the random distribution of a certain number of points are to be analyzed, and the underlying characteristics associated with the point are selected by the observer. Additionally, the statistical analysis of coral coverage in each image is performed to assess the transect as a whole; the results are exported automatically to spreadsheets. A similar procedure is followed for individual coral colonies, which allows tracing temporal changes in coverage.

Based on spreadsheets with the data on both transects and individual colonies, temporal changes are analyzed, comparing the data obtained during a calendar year with a three-month gap and assessing whether there were significant changes in total coral coverage and individual colonies. The data reported by a lookout diver on divers’ behavior control sheets allow us to determine the number and the type of impact. To assess changes due to the diving activities, comparisons within each transect and between them are carried out, and a possible correlation between the impact and diving activities is searched for. The assessment technique is still under revision; thus, only preliminary results are available. Most likely, after the COVID-19 pandemic, more intensive diving activities, which would cause a more pronounced negative impact by divers on the coral reef ecosystem under study, are expected.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to the staff of Dorado Buceo (Veracruz, Ver., Mexico) and the students and ex-students of the ICIMAPUV (Angélica Vásquez-Machorro, Merari Contreras-Juárez and Melissa Mayorga-Martínez) for logistic and technical support, to Natalia A. Okolodkova (Mexico City, Mexico) for her help with the plate of photographs and to Marcia M. Gowing (Seattle, WA, USA) for improving the English style. The National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACyT) provided a scholarship for MVM in 2020-2021; the study is a part of his MSc thesis entitled “Assessment of diver impact on hermatypic corals of the Anegada de Adentro Reef, the Veracruzan Reef System National Park”.

References

- Roche R, Harvey CV, Harvey JJ, Kavanagh A, Donald M, et al. (2016) Recreational diving impacts on coral reefs and the adoption of environmentally responsible practices within the SCUBA diving industry. 58: 107-116.

- Hawking JP, Roberts CM (1993) Effects of recreational diving on coral reefs. Trampling of reef-flat communities. Journal of Applied Ecology 30(1): 25-30.

- Lindgren A (2008) Environmental management and education: The case of PADI. In: Garrod B, Gössling S (Eds.), New frontiers in marine tourism: Diving experiences, sustainability, management. Netherlands.

- Townsend CR (2008) Ecological applications: Toward a sustainable world. Australia.

- Luna B, Valle PC, Sánchez LJ (2009) Benthic impacts of recreational divers in a Mediterranean marine protected area. ICES Journal of Marine Science 66(3): 517-523.

- Melo S, Victoria M, Pérez EH (2014) Guía de identificación de corales más comunes en los arrecifes de Veracruz. University of Veracruz, Mexico.

© 2021 Yuri B Okolodkov. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)