- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography

Juvenile (YOY) Black Sea Bass Density on Crepidula Reef Versus Sand/Sponge Habitat in Upper Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts

William A Hubbard*, Michael J Elliot and Francis J Veale

Department of Marine Science Safety and Environmental Protection, Massachusetts Maritime Academy, Buzzards Bay, USA

*Corresponding author: William A Hubbard, Department of Marine Science Safety and Environmental Protection, Massachusetts Maritime Academy, Buzzards Bay, USA

Submission: July 02, 2020;Published: uly 10, 2020

ISSN 2578-031X Volume3 Issue4

Abstract

The black sea bass Centropristis striata population of the Northwest Atlantic has been expanding over the past decade throughout its northern extent in Massachusetts waters. As abundance has increased in the coastal waters of Massachusetts, valuable commercial and recreational fisheries have developed. Relatively little is known about the habitat requirements for black sea bass at different life stages in Massachusetts waters. Identification and conservation of critical habitats is an essential component of sustainable fisheries management. In this study we conducted underwater video transects in Buzzards Bay, MA to better understand the habitats used by young-of-the-year black sea bass. We specifically focused on a comparison between Crepidula fornicata shell reefs and sandy/sponge habitats. Our results suggest that juvenile, young-of-the-year black sea bass are present in statistically significant higher densities on the Crepidula fornicata shell reefs than in the sandy bottom habitat. This sampling identified an average of eight times more fish on the shell reef habitat, implicating the shell reefs as a potential nursery habitat in Massachusetts waters. Crepidula reefs should be considered for designation as Special, Sensitive or Unique resource in the Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan.

Keywords: Massachusetts; Black sea; Coastal water; Finfish species; Cape cod

Introduction

Climate mediated shifts in the ranges and distribution of fish populations pose important challenges for management and conservation. In the Northwest Atlantic, shifting species distributions have been documented for a suite of recreationally, commercially, and ecologically important finfish species [1]. As species expand into areas previously unoccupied, it is imperative to understand how they are using habitats in these new areas and which habitats may require further protection to ensure sustainability and productivity of fish populations throughout their contemporary range.

Black sea bass Centropristis striata are distributed from Cape Cod, Massachusetts south to the Gulf of Mexico. Two distinct genetic stocks have been identified, delineating this population into a Northern and Southern stock, with Cape Hatteras, North Carolina serving as the breakpoint between the two [2,3]. Over the past few decades, the Northern black sea bass stock has undergone a rapid northward shift in its center of distribution [4,5]. Black sea bass is presently one of the largest recreational fisheries in the state of Massachusetts, with recreational anglers harvesting an estimated 743,617lb in 2017. Understanding how this burgeoning population is using different habitats at different life stages, in the coastal waters of Massachusetts, is imperative for conservation and sustainable management. In this paper, we focus on the habitat use of juvenile black sea bass in the northern extent of their range, Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts.

Like many of the seasonally migratory species that inhabit the coastal waters of the northeastern United States, black sea bass occupy the inshore waters for the spring and summer months, and then migrate to deeper warmer waters to overwinter [5,6]. Spawning activity occurs annually from May through July, with the peak in June [7,8]. Once juveniles settle out of the pelagic stage and become demersal, cover and prey availability become limiting factors to their success [9]. Young-of-the-year (YOY; age 0) utilize the shallow, nearshore habitats until their first offshore migration in the fall of the same year they were hatched. Structured habitats are favored over open sandy or muddy bottom [10]. In addition, YOY exhibit site fidelity and territorial behaviors during their juvenile phase [11,12].

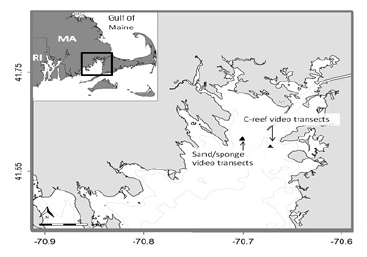

Juvenile black sea bass are known to forage on rocky and shell substrates (Figure 1); dominant prey for juveniles include crustaceans and small fish [13]. Recent benthic studies in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts have identified associations between juvenile black sea bass and several large Crepidula fornicata (common slipper shell; hereafter, crepidula) shell reefs extending to over forty hectares (approximately one hundred acres) each [14]. These shell reefs may be important forage and shelter areas that allow many valuable recreational finfish species to proliferate in Massachusetts. In Europe, crepidula are considered invasive, imported with oysters from North America, and have been expanding with warming sea temperatures [15]. Crepidula are native to Massachusetts waters, however, there is evidence that their abundance and distribution has increased in recent decades [16]. Despite the prevalence of black sea bass in Massachusetts waters, relatively little is known about their habitat use at different life stages.

Figure 1: Still screen shot from video transect showing juvenile black sea bass on a Crepidula fornicata shell reef in Buzzards Bay, MA.

In this study, we sought to better understand YOY black sea bass occupancy of different habitats to identify important nursery habitats [17], defined nursery habitats as those that contribute a greater than average number of individuals to the adult population on a per-unit-area basis as compared to other juvenile habitats. We used underwater video transects to quantify black sea bass YOY density in two different habitat types, structured (Crepidula reef) and non-structured (sandy bottom). Understanding how different habitats are contributing to recruitment to the adult population is important for the protection of important habitats, but also to improve our ability to predict future productivity and recruitment based on availability of optimal habitat.

Method

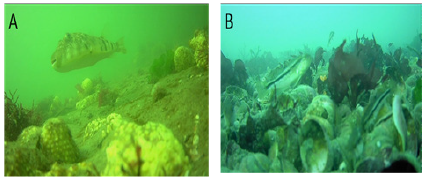

On 23 and 24 of August 2016, we conducted two sampling events using high definition (Sea viewer 6000) underwater video cameras to produce video recordings (Sea viewer HDMI H.264 Recorder) of a Crepidula reef (C-reef) and a sandy habitat with the massive form morphology of boring sponge Cliona celata. In upper Buzzards Bay the dominant substrates are sand, sand with sponge, shell reefs, macro algae beds and submerged aquatic vegetation. The videos were recorded from a surface deployed camera in profile view and were post-processed to produce screen shot stills used to document and quantify juvenile black sea bass densities. The two sampling stations were located 2.5 kilometers apart, in upper (eastern) Buzzards Bay, at the end of Hog Island channel - just outside Stony Dike (Figure 2). The C-reef video was in the general vicinity of 41ᵒ40’28.82”N/ 70ᵒ40’20.35”W, while the sand/sponge video was in the general vicinity of 41ᵒ40’56.93”N/ -70ᵒ42’3.26”W. Video transects were completed at the two sampling locations between depths of five and six meters. We obtained still screen shots from the video transect data (Figure 3). All screen shots were reviewed in full screen, in eight zoom quadrants and then with enhanced contrast/color scaling. Images with at least 90% of the field-of-view suitable for examination were retained for the analysis. Screen shots that were out of focus, taken in water too turbid for examination, or were generally of poor quality were excluded.

Figure 2: Map showing the location of the video transects for each habitat type in Buzzards Bay, MA.

Figure 3: Sand/sponge (A) and C-reef shell (B) habitat screen shots from Buzzards Bay video transects.

Result

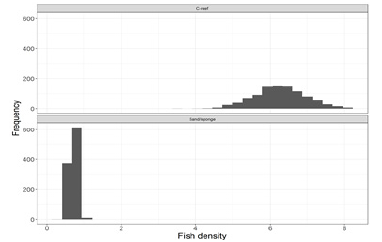

Thirty-three screen shots from the C-reef and 61 from the sand/sponge habitat were examined in detail, and numbers of Young-of-the-Year (YOY) black sea bass were recorded for each screen shot. The mean fish density from the video transect observations was 6.30 fish/m2 (Sd=4.16) in the C-reef habitat and 0.71 fish/m2 (Sd=0.82) in the sand/sponge habitat. The lack of overlap between the distributions of bootstrapped mean fish density estimates, by habitat, provides strong evidence of a significant difference in fish density between the two habitats (Figure 4). In addition, there were no bootstrap t-values that were greater than or equal to the Student’s t-statistic (t=7.65); further supporting a rejection of the null hypothesis that fish density in the two habitat types is equal (p≈0). The C-reef habitat supported eight times the density of fish observed in the sandy bottom habitat in our study area.

Figure 4: Distribution of bootstrapped mean fish density estimates (fish/m2), by habitat type.

Discussion

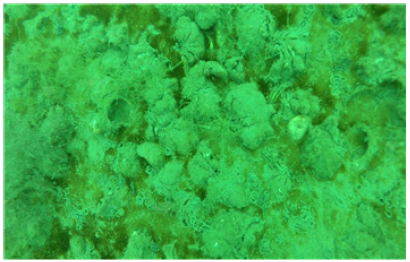

The C-reef slipper shell residents produce a nutrient rich waste that settles in among the stacked shell “curls”. This rich substrate is the result of the water filtration provided by Crepidula fornicata, a unique organism as it is a filter feeding gastropod. Field and laboratory observations indicate the filtration and conversion to a fine organic matter is prolific. Numerous crabs and amphipods are associated with the benthic community of this shell habitat [18]. The small surficial polychaete Polygordius apendiculata can also be a significant forage component of some C-reef habitat. Polygordius has reached densities of over 10,000 organisms per square meter (up to 11700/m2) on some reefs sampled for benthic community composition [16]; (Figure 5). Other small polychaetes, gastropods and amphipods colonize the interstitial shell spaces providing a diverse symbiotic community. This diverse benthic community provides a significant forage base for juvenile black sea bass and other species [13]. Our results suggest that C-reef habitat could be important nursery habitat for YOY juvenile black sea bass, contributing far greater numbers per-unit-area than the sandy/sponge habitats. [19] have proposed that it is not just the per-unit-area contributions that should define nursery habitats, but the overall contributions of habitat.

If we make a broad assumption that the field-of-view of each high definition video frame is one square meter, we can allocate the C-reefs to hosting 6.3 juvenile black sea bass per square meter. This is not an inference that this is the quantifiable carrying capacity relationship of these two habitats, just an indication of black sea bass preference for shell versus sand/sponge habitat. The 2017 report for benthic mapping in Buzzards Bay [14] identified seven areas of dense C-reef habitat in the upper Bay. One is as large as 53 hectares and several more are over 40 hectares. Therefore, a minimum of 700 acres (2.833km2) were documented in the study area; an area predicted to host over seventeen million (17,847,900) YOY. In 2014, the United States Geologic Survey (USGS) conducted a hydroacoustic survey Buzzards Bay which effectively mapped “Shell Zones” [20].

Figure 5: Still screen shot from video transect showing the small surficial polychaete Polygordius apendiculata, which is a significant forage component for black sea bass in the C-reef habitat.

Shell Zones are areas of high density crepidula beds, identified by high acoustic backscatter in areas of fine-grained surficial sediments, and verified using digital photographs. The Shell Zones identified cover 14.8 km2, which is 2% of the Buzzards Bay sea floor by area; this area is likely larger but has yet to be verified with photographs of the bottom habitat [20]. Assuming if the density we observed in the C-reef habitat is representative of the larger Bay, we estimate this habitat could support approximately 93,240,000 YOY black sea bass.

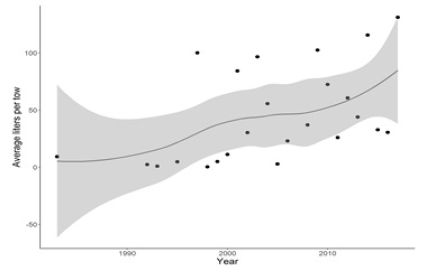

Buzzards Bay is a dynamic ecosystem and has fluctuated dramatically through time. The contemporary habitats observed throughout the bay have changed considerably from the habitats in the region 50 years ago. In 1955 a benthic infaunal survey of Buzzards Bay was conducted [21] and was then repeated in 2011 and 2012 [16]. The comparison between the two time periods showed a shift towards higher nutrient concentrations, warmer temperatures, reduction in species diversity, and a restructuring of the benthic community. One of the marked shifts in benthic species composition was the proliferation of crepidula beds. Crepidula was absent from the 1955 samples but showed up as the dominant species at two locations in 2011/2012. In addition, the presence of cprepidula in the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries’ inshore trawl survey [22], a synoptic trawl survey that has sampled the coastal waters of Massachusetts twice per year (May and September) since 1978, has generally increased through time (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Average liters per tow of Crepidula fornicata in the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries inshore trawl survey, from 1983-2017. The gray line represents a loess curve through the data points with the 95% confidence interval depicted by the light gray shaded area.

Climate change and anthropogenic inputs were suggested as potential drivers contributing to the proliferation of the C-reef habitat in Buzzards Bay [23]. Likewise, warming water temperatures has been suggested as an important driving force in the expansion of the black sea bass population into Massachusetts waters [5]. Black sea bass are a prized game fish so as their distribution has shifted north, important recreational and commercial fisheries have developed in the region. The recreational harvest of adult black sea bass averaged 352,443 fish per year during the decade from 2006 to 2017, state-wide in Massachusetts [24]. Adapting to climate change requires an understanding of how different habitats are used at different life stages for a wide range of species. Our results suggest that C-reef habitats contribute substantially to the adult black sea bass population on a per-unit-area. These results combined with the USGS mapping efforts suggest that C-reef is also a large component of the overall bottom habitat in Buzzards Bay; therefore, supporting the classification as important nursery habitat. The tremendous ecological productivity of the Massachusetts crepidula shell reef habitat should be protected. The reliance of important fishery resources on this benthic structure, such as the black sea bass juvenile phase, warrants evaluation as a Special, Sensitive, or Unique (SSU) resource in the Massachusetts Coastal Zone Ocean Management Plan.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Massachusetts Environmental Trust (https://www.mass.gov/environmentallicense- plates) Coastal America Foundation (www. CoastalAmericaFoundation.org).

References

- Nye JA, Link JS, Hare JA, Overholtz WJ (2009) Changing spatial distribution of fish stocks in relation to climate and population size on the Northeast United States continental shelf. Marine Ecology Progress Series 393: 111-129.

- Roy E, Quattro J, Greig T (2012) Genetic management of black sea bass: Influence of biogeographic barriers on population structure. Marine and Coastal Fisheries 4(1): 391-402.

- Cartney MA, Burton ML, Lima TG (2013) Mitochondrial DNA differentiation between populations of black sea bass (Centropristis striata) across Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (USA). Journal of Biogeography 40(7): 1386-1398.

- Bell RJ, Richardson DE, Hare JA, Lynch PD, Fratantoni PS (2015) Disentangling the effects of climate, abundance, and size on the distribution of marine fish: An example based on four stocks from the Northeast US shelf. ICES Journal of Marine Science 72(5): 1311-1322.

- Miller AS, Shepherd GR, Fratantoni PS (2016) Offshore habitat preference of overwintering juvenile and adult black sea bass, Centropristis striata, and the relationship to year-class success. Plos One 11(1): e0147627.

- Collette B, Klein G (2002) Bigelow and Schroeder’s Fishes of the Gulf of Maine. Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington DC, USA.

- Musick JA, Mercer LP (1977) Seasonal distribution of black sea bass, Centropristis striata, in the Mid-Atlantic bight with comments on the ecology and fisheries of the species. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 106(1): 12-25.

- Drohan A, Manderson J, Packer D (2007) Essential fish habitat source document: Black sea bass, Centropristis striata, life history and habitat characteristics. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE 200: 68.

- Richards WJ, Lindeman KC (1987) Recruitment dynamics of reef fishes: planktonic processes, settlement and demersal ecologies, and fishery analysis. Bulletin of Marine Science 41(2): 392-410.

- Allen DM, Clymer JP, Herman SS (1978) Fishes of the Hereford inlet estuary, southern New Jersey. Lehigh University, USA.

- Able KW, Hales LS (1997) Movements of juvenile black sea bass Centropristis striata (linnaeus) in a southern New Jersey estuary. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 213(2): 153-167.

- Werme CE (1981) Resource partitioning in a salt marsh fish community.

- Kirnmel J (1973) Food and feeding of fishes from Magothy Bay, Virginia. Old Dominion University, Virginia.

- Hubbard W, Elliot M, Veale F (2018) Benthic studies in Buzzards Bay, MA. Report, Massachusetts Maritime Academy and Coastal America Foundation, USA.

- Montaudouin X, Blanchet H, Hippert B (2017) Relationship between the invasive slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata and benthic megafauna structure and diversity, in Arcachon Bay. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, p. 1-12.

- Hubbard WA (2016) Benthic studies in upper Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts: 2011/12 as compared to 1955. Marine Ecology 37(3): 532-542.

- Beck MW, Heck KL, Able KW, Childers DL, Eggleston DB, et al. (2001) The identification, conservation, and management of estuarine and marine nurseries for fish and invertebrates: a better understanding of the habitats that serve as nurseries for marine species and the factors that create site-specific variability in nursery quality will improve conservation and management of these areas. Bioscience 51(8): 633-641.

- Able K, Fahay M, Shepherd G (1996) Early life history of black sea bass, Centropristis striata, in the Mid-Atlantic bight and a New Jersey estuary. Oceanographic Literature Review 6(43): 609.

- Dahlgren CP, Kellison GT, Adams AJ, Gillanders BM, Kendall MS et al. (2006) Marine nurseries and effective juvenile habitats: Concepts and applications. Marine Biology and Fisheries 312: 291-295.

- Foster D (2014) Physiographic shell zones of the sea floor of buzzards bay, massachusetts. Coastal and Marine Geology Program, Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, USA.

- Sanders HL (1958) Benthic studies in Buzzards Bay. I. Animal-sediment relationships. Limnology and Oceanography 3(3): 245-258.

- King JR, Camisa MJ, Manfredi VM (2010) Massachusetts division of marine fisheries trawl survey effort, lists of species recorded, and bottom temperature trends, 1978-2007. Technical report, Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, USA.

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ (1994) An introduction to the bootstrap. CRC press, USA.

- Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (2017) 2017 Review of the Atlantic States marine fisheries commission fishery management plan for the 2016 black sea bass fishery. Arlington, VA.

© 2020 William A Hubbard. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)