- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Marine Biology and Oceanography: Open Access

Seasonal Changes in Benthic Fish Population Influenced by Salinity and Sediment Morphology in a Tropical Bay

Srinivasa MR, Vijaya Bhanu C and Annapurna C*

Department of Zoology, Andhra University, India

*Corresponding author: Annapurna C, Department of Zoology, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam-530 003, India

Submission: November 13, 2017; Published: February 23, 2018

ISSN: 2578-031X Volume1 Issue3

Abstract

Coastal Bays are productive habitats used by a variety of fishes and other benthic organisms but little information is available on the ecology and population dynamics of benthic fishes of coastal bays in the tropical zones. This paper deals with the biodiversity, faunal assemblages, seasonal variations in the benthic fish population of a shallow tropical Bay named Nizampatnam Bay, located in southern province of Bay of Bengal, East coast of India. The standing stock of benthic fishes and associated environmental factors of the study area were also reported in this paper. Sampling was done in two successive post monsoons and pre monsoons during 2006 to 2008. Water and sediment samples were collected from 20 stations covering 10, 20 and 30 m zones. Altogether, 128 biological samples were collected with a Naturalist's dredge. Thirty benthic fish species belonging to 21 genera, 12 families, 6 orders and 1 class were recorded in this study dominated by Cociella crocodilus and Pisodonophis boro. The mean of Shannon Wiener diversity index H' was recorded 1.3±0.4 during post-monsoon and 1.2±0.2 at pre-monsoon suggesting that the benthic fish diversity of this Bay was poor. Multivariate (Bray-Curtis similarity) analyses typified two large groups of stations representing respectively the post monsoon and pre monsoon periods. The two faunal associations recognized off the Nizampatnam Bay were, Cociella crocodilus, Cynoglossus lida, Cynoglossus punticeps and Astroscopus zephyreus (Group I) representing post-monsoon and Pisodonophis boro, Trichonotus arabicus, Acentrogobius cyanosmos and Pseudorhombus elevatus (Group II) representing pre-monsoon. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) showed that salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, % sand and sediment mean particle diameter influenced seasonal variability in the distribution of benthic fish population. This study will provide the baseline information on the biodiversity, ecology and seasonal variations in benthic fish associations of this area and will contribute to the Pisces list of Indian seas.

Keywords: Species diversity; Seasonal variations; Benthic fishes; PRIMER; Canoco; Physicochemical properties; Nizampatnam bay; Bay of Bengal

Introduction

Approximately 98% of all marine species are supposed to belong to the benthos [1]. Benthic organisms link the primary producers, such as phytoplankton with the higher trophic levels, such as finfish, by consuming phytoplankton and then being consumed by larger organisms. Many benthic fish species rely on other bottom prey as food sources for part of, or in some cases, all of their life history [2] and inturn become the rich source of food for fishes in bathypelagic and mesopelagic zones. Hence, they play a very important role in the marine food web. As benthic fishes are a good source of food for mesopelagic and benthopelagic finfishes, it is very important to know their status in an ecosystem for a better understanding of the fishery management.

Communities of fishes on the continental shelf have rarely been studied beyond the compilation of species list for given areas. Information on benthic fish assemblages is particularly scarce in the Bay of Bengal where demersal fish are heavily exploited as principal targets or as by-catch [3]. Most studies have examined mega faunal assemblages, while, only few studies of fish community structure have focused on patterns of spatial and temporal variation in composition, abundance and distribution of demersal fish assemblages of the continental shelf and slope at higher latitudes [4-10]. Even though on a world wide scale there are probably many areas of shelf and slope that have not been explored, they were evaluated to a little extent in tropical waters [11-14]. Yet, few benthic studies edging the Pisces have to be conducted in the tropics compared with higher latitudes. In the Indian context, demersal fish assemblages have been examined by few authors over a few decades in Arabian Sea (west coast of India) [15-19]. In the Bay of Bengal (east coast of India), comparatively less work was done on the demersal fish component [20-22]. Even these are mainly directed towards the whole demersal fish (collected with huge trawl nets) community with cursory accounts of ecology and lists of fauna. But studies focusing exclusively on benthic fish (collected with small Naturalist's dredge) component are scarce in both temperate and tropical zones.

The present study area, Nizampatnam Bay (Lat. 15° 28N' to 15° 48' N and Long 80° 17' to 80° 47' E) is a shallow tropical Bay located in the southern province of Andhra Pradesh, Bay of Bengal, East coast of India. This Bay has a coastline of 122km occupying an area of 1825Sq. Km with a maximum depth of 34m. The discharges from the river, saltpans, aquaculture ponds and mangroves built along the coastline are influencing the ecology of the bay fauna. Hence; a study was conducted to evaluate the seasonal variability in the diversity and faunal associations of macrobenthic population and the effect of different physicochemical parameters on the same. From the available macrobenthos data, benthic fish component was segregated and evaluated for seasonal variability. This paper is the first available data set on the benthic fish species density, diversity, assemblages and influence of environmental factors on benthic fishes from Bay of Bengal, East coast of India.

Material and Methods

During this investigation, four cruises (FKKD-fishing trawler) were conducted through two successive Post-monsoon seasons (October 2006 and November 2007) and two pre-monsoons (March 2006 and 2007) between latitudes 150 28' to 150 48' N and longitudes 800 17' to 800 47' E in Nizampatnam Bay (Figure 1). Observations on physicochemical characteristics of the seawater temperature, dissolved oxygen and salinity were made using an onboard WTW probe. Sediment samples were collected using a van Veen grab (Hydrobios, Kiel, Germany) having a mouth area of 0.1m2. These samples were oven dried at 60 0C and stored. The sediment texture was estimated using a particle size analyzer Master sizer 2000, Malvin Instruments (USA) for soft sediments and Sieve Shaker, Retsch instrument (Germany) for hard sediments. Organic matter (%) content was determined by the Wet Oxidation method of Walkley-Black using rapid titration procedure but as modified by [21].

Figure 1: Study Area: locations of 20 sampling sites in Nizampatnam Bay.

Altogether 128 biological (dredge) samples were collected with a Naturalist's dredge. On board, all the organisms were washed with seawater in a large metal tray and after separation the animals were carefully transferred into polythene containers, labeled and preserved in 7% formaldehyde/methylated alcohol for later study. In the laboratory, benthic fishes were segregated, counted (ind. haul-1) and identified up to species level using standard identification keys [23-26]. Debatable identifications were mostly referred to taxonomists at the Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata.

The data was subjected to univariate analyses carried out in PRIMER 6.1 [27]. Shannon-Wiener diversity (H' Loge), Margalef richness (d) and Pielou's evenness (J') were determined according to routines implemented in PRIMER. Multivariate analysis consisted 25.0 0C (st.9, pre-monsoon I) to 34.1 0C (st.13, of estimating Bray Curtis similarity after suitable transformation of sample abundance data. The similarity matrix was subjected to both clustering (hierarchical agglomerative method using group- average linking) and ordination (non-metric multidimensional scaling, MDS) using PRIMER 6. Significance tests of sample groupings were made using the ANOSIM (1-way) randomization test. The contribution of each species to groupings noticed in the clustering and ordination analysis was examined by SIMPER (similarity percentages) implemented in PRIMER [28] to quantify percentage contribution of each species to similarity within each group (i.e. characteristic) of samples and to dissimilarity between different groups. Other routines (e.g. BVSTEP), namely stepwise searches of combinations of species considered to be ultimately responsible for the observed pattern in the biotic assemblages, were also carried out using PRIMER. Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) [29] was performed to possible correlations between environmental variables, benthic fish species and variance in site pattern, using a form of stepwise regression. A Monte Carlo permutation test (unrestricted) was used to determine the significance of species environment relations. Simple multiple regressions of environmental parameters against biological indices (H', J and d) were performed in SPSS 14 to explain the extent of variance in the distribution of biological indices influence by a set of environmental parameters.

Hydrographical parameters

Figure 2: Temperature (oC), Salinity (PSU) and Dissolved Oxygen (ml.l-1) from Nizampatnam Bay during different seasons.

Bottom water temperature in the study area varied from 25.0 0C (st.9, pre-monsoon I) to 34.1 0C (st.13, post-monsoon II),mean 29.3±0.18 indicating a significant variation through various monsoon periods with much warmer bottom waters in postmonsoon than pre-monsoon (P≤0.01) (Figure 2a). On the whole, bottom water salinity varied from 24.8 PSU (st.6, pre monsoon I) to 36.8 PSU (st.4, pre-monsoon I and st.18, pre monsoon II), with mean 32.2±0.38. The bottom waters of this Bay were more saline in pre-monsoon than in the post monsoon. The differences in the bottom water salinity recorded during different monsoons varied significantly (P≤0.01) between themselves (Figure 2b). The dissolved oxygen concentrations of bottom waters ranged from 1.34ml.l-1 (st.9, post-monsoon I) to 5.82ml.l-1 (st.6, post-monsoon II) , mean 3.64±0.11. The pattern of distribution of dissolved oxygen through different monsoons is in synchro distribution of temperature in the Bay. The differences in the bottom water dissolved oxygen concentrations were varying significantly in between various monsoon periods (P≤0.01) (Figure 2c).

Sediment characteristics

The predominant sediment texture in the Nizampatnam Bay was clayey silt (11 stations) followed by sandy (5 stations), silty (2 stations) and mixed type (more or less in equal proportions of sand, silt and clay-2 stations) (Figure 3). At stations that lie nearer to the shoreline, the sediments consisted of relatively soft (mud) substrata (sts. 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, 14, 15 and 20). Sand increased towards the deeper regions (st. 9, 10, 13, 17 and 18), silt was usually high in stations 5 & 12 and mixed type sediment is observed in stations 16 & 19 (Figure 3). Organic matter (%) ranged from 0.26 % to 2.20 % (1.16±0.06) and negatively correlated with depth (r = -0.327, p = 0.008).

Figure 3: Sediment texture in the Nizampatnam Bay.

Mean particle diameter (MPD) of sediment varied between 4.834.83μm and 888.0p.rn (153.7±30.9) showing an inclination with depth. From the above observations, it can be concluded that organic matter, % silt and clay declined with inclination in depth, whereas MPD and % sand increased with depth in the Nizampatnam Bay It is generally believed that sediments with coarse particles are deficient in organic matter whereas fine grain sediments show organic enrichment.

Population dynamics

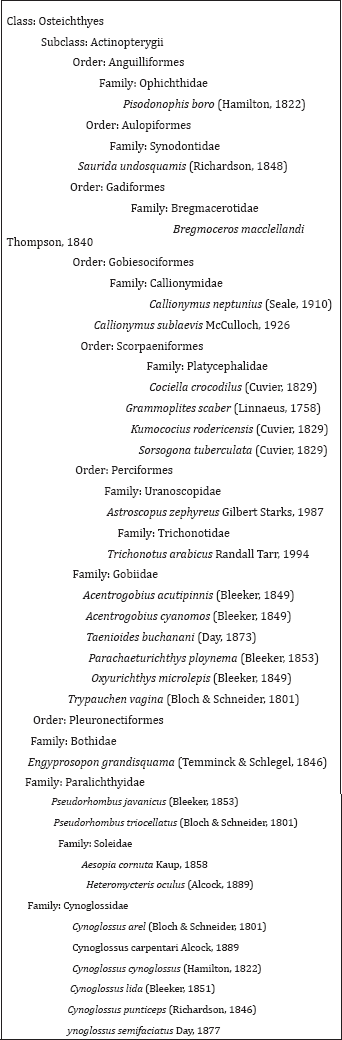

During this study, 225 species of epifauna belonging to 129 genera and 59 families representing 11 divergent taxa were encountered from phylum Porifera to Pisces. The benthic fish component constituted 30 species belonging to 20 genera, 12 families, 7 orders and 1 class (Table 1). Altogether 348 individuals of benthic fishes were encountered in the dredge samples collected from the study area. Numerically Cociella crocodiles (86 nos., 24.7%), Pisodonophis boro (72 nos., 20.7%), Cynoglossus punticeps (37 nos., 10.6%), Trichonotus arabicus (32 nos., 9.2%), Cynoglossus lida (31 nos., 8.9%), Acentrogobius cyanosmos (21 nos., 6.0%), Pseudorhombus elevatus (20 nos., 5.7%), Astroscopus zephyreus (9 nos., 2.6%) dominated the total benthic fish population contributing about 88.5% (Table 1).

Table 1: Taxonomic list of benthic fish species encountered during the study.

Species diversity was estimated according to the Shannon- Weiner H' (loge), Pielou's evenness (J') and Margalef richness "d" indices. Benthic fish diversity (Shannon-Wiener H') was recorded high in the post-monsoons (1.8±0.4) than pre-monsoons (1.1±0.18) and varied between 0.56 and to 2.20 (mean 1.27±0.35). Number of benthic fish species (S) varied from 2 to 10 (4±2) and no. of individuals (N) ranged between 4 and 19 (8±3). Species richness (Margalef d') varied from 0.62 to 3.51 (1.65±0.63) and evenness J' ranged from 0.58 to 1.00 with mean 0.9±0.09. Bray-Curtis similarity analysis (assemblages) followed by an ordination through MDS on benthic fish abundance data (nos. haul-1) was undertaken. Figure 4 displays the hierarchical clustering, using group average linking on species abundance data representing the stations grouping into two clusters at 65% similarity. These consisted of Group I (28) samples representing post-monsoon seasons and Group II (16) samples representing pre-monsoon seasons. A corresponding cluster of these sites/samples superimposed with season categories is presented in the form of Multi Dimensional Scaling Plot-MDS plot (Figure 4b). ANOSIM test for the 2 groups demonstrated significant differences (Global R = 0.609, p<0.001).

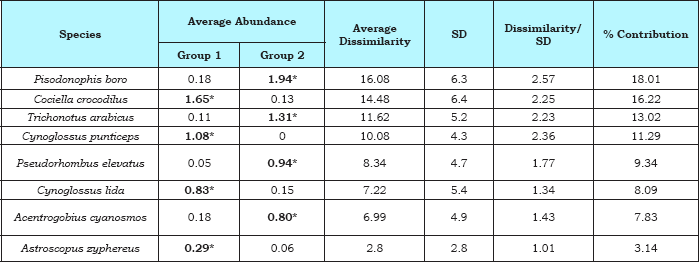

The SIMPER analysis for benthic fish abundance of present study showed characterizing species within each season group indicating the existence of different faunal associations along / among different seasons. The two faunal assemblages recognized off the Nizampatnam Bay were, Group I (post-monsoon) constituted by Cociella crocodilus, Cynoglossus lida, Cynoglossus punticeps and Astroscopus zephyreus association and Group II (pre-monsoon) distinguished by Pisodonophis boro, Trichonotus arabicus, Acentrogobius cyanosmos and Pseudorhombus elevatus assemblage (Table 2).

Figure 4: Benthic Fish Assemblages of Nizampatnam Bay

a) Dendrogram clustering

b) MDS ordination of sampling sites using group average linking of Bray-Curtis Similarity (Square root transformed data) at 60 % similarity.

Table 2: Results of SIMPER analysis for benthic fish species off Nizampatnam Bay: determining species (bold) for each season. Taxa are ranked according to their average contribution to dissimilarity between seasons. Group I: post-monsoon; Group II: premonsoon; Average dissimilarity = 87.42 %.

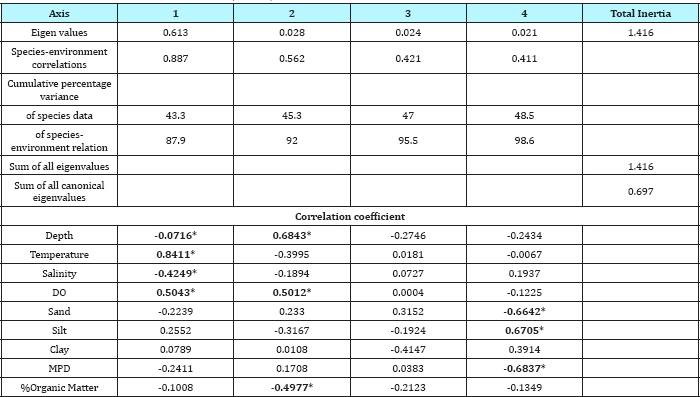

Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) implemented in CANOCO was used to ascertain the influence of environmental factors on benthic fish species distribution at the study sites. We found that the distributions were almost the same whether the entire set of species or just the discriminating species identified through BVSTEP analysis were used. The best subset of benthic fish species found by the BVSTEP procedure seemed to be comprised by the same eight species resulted in SIMPER from the list of 30 species encountered from the study area. Monte Carlo permutation tests (with forward selection) were used to identify which environmental variables (out of 9) explained the variance significantly (p<0.05 level) in benthic fish distribution and species pattern. From the CCA, it was found that four ordination axes cumulatively explained 98.6% of the species variance with the first two axes being important explaining 87.9 to 92.0% of the species variance (Table 3). The eigenvalues for the first two canonical axes were 0.613 and 0.028 respectively. The environmental axis 1 (87.9%), strongly associated with depth (r =-0.716), temperature (r = 0.8411), salinity (r = -0.4249) and dissolved oxygen (r = 0.5043). While axis 2 showed significant correlations with depth (r = 6843) and dissolved oxygen (r = 0.5012), Axis 4 was strongly associated with % sand (r = -0.6642), % silt (r = 0.6705) and MPD (r = -0.6837). From the triplot, it was clearly evident that the benthic fish community of this Bay was segregated into two groups. Group I typified the stations monitored in post-monsoon season constituted the Cociella crocodilus assemblage and Group II contains the stations monitored during pre-monsoon represented by Pisodonophis boro association.

Table 3: Results of CCA; eigenvalues, species-enivironment correlation and percentage variance for Nizampatnam Bay for benthic fish species abundance data; weighted correlation between enivironment variables and CCA axes. Environmental variables identified by Monte Carlo permutation tests based on forward selection with 499 unrestricted permutation; variance of environmental variables accepted at P<0.05, * Significance at P<0.05(in bold).

Discussion

Spatial and temporal heterogeneity among macro benthos in Bay environments under tropical conditions has been assigned to events taking place in sediment properties, ambient salinity and such other environmental factors [30]. Several factors like location, depth, and distance from shore, river proximity and oceanographic environmental parameters (bottom water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, sediment organic matter, mean particle diameter and texture) appeared to be important for determining benthic fish distribution patterns in this study. In the Bay water body at Nizampatnam, terrigenous inputs through river discharge, materials flowing out of salt pans, estuaries, mangroves and transport through neritic inflow appeared to determine the hydrography and sediment granulometry that in turn could have influenced distribution of benthic fishes [31].

Altogether 30 species of benthic fish species representing 20 genera, 12 families, 7 orders and 1 class were encountered in this study. The average values of Shannon-Weiner diversity index H' recorded during post-monsoon was 1.3±0.4 and in pre-monsoon was 1.2±0.3. The benthic fish diversity of Nizampatnam Bay can be considered as poor as the mean H' recorded in this study was 1.3 and 1.2. Buchanan [32], Longhurst [33], Desai & Kutty [34] have also indicated that species diversity was poor or moderate in tropical benthic communities they studied.

Multivariate analyses (Bray-Curtis Similarity) defined two distinctive benthic fish assemblages from the study area, namely Cociella crocodilus, Cynoglossus lida, Cynoglossus punticeps and Astroscopus zephyreus association (Group I, samples from post-monsoon) and Pisodonophis boro, Trichonotus arabicus, Acentrogobius cyanosmos and Pseudorhombus elevatus assemblage (Group II, samples from pre-monsoon). Generally, control by physical forces (monsoons, temperature, and salinity), edaphic factors, inter specific competitions through niche selection etc. has the main criteria for the variability in benthic faunal assemblages in tropical waters [35-38].

Using CCA routine implemented in CANOCO, benthic fish communities were linked with environmental variables (depth, bottom water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, sediment texture, mean particle diameter and organic matter). The first axis of the CCA had an eigenvalues of 0.613, implying a large percentage (87.9) of explained variance [28,39]. Together, the four ordination axes cumulatively explained 98.6% of the species variance with the first two axes being important explaining 87.9 to 92.0% of the species variance (Table 3). The noteworthy feature, however, is the high correlation (weighted correlation coefficient >0.4) between faunal abundance and environmental variables on all 4 CCA axes.

Figure 5: Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) showing scatter plot for 64 benthic fish samples from the Nizampatnam Bay. (b) CCA showing 8 most important benthic fish species and environmental variables. Vector lines represent the relationship of significant environmental variables to the ordination axes; their length is proportional to their relative significance. DO: Dissolved oxygen, MPD: Mean particle diameter.

From the triplot in CCA ordination (Figure 5), it is clearly evident that the distribution of Pisodonophis boro, Trichonotus arabicus, Acentrogobius cyanosmos and Pseudorhombus elevatus (Group II, pre-monsoon) assemblage seemed to prefer high saline waters and deeper areas with coarse sediments. The Nizampatnam Bay's salinity varies widely from season to season and from year to year, depending on the amount of fresh water flowing from its rivers. During drier months (pre-monsoon), the Bay is usually saltier. Salinity also increases with depth. Fresh water remains at the surface because it is less dense than salt water. The water on the Bay's eastern shore tends to be saltier than water on the western side. This is due to two factors: Most fresh water enters the Bay from its northern and western tributaries, through the Krishna River. So, saltier water moving up the Bay veers toward the eastern parts of the Bay. These high saline waters available in the deeper zones of this Bay favoured the survival of Pisodonophis boro, Trichonotus arabicus, Acentrogobius cyanosmos and Pseudorhombus elevatus association which is sensitive to salinity fluctuations. These four fishes that occur in the pre-monsoon are predatory as they are surviving in sediments with high sand proportions dominated by epifauna benthos [40].

In contrast, Cociella crocodilus, Cynoglossus lida, Cynoglossus punticeps and Astroscopus zephyreus (Group I, post-monsoon) association has a negative relation with salinity and preferred the locations with soft (high mud clay and silt proportions) substratum. During the post monsoon, the fluctuations in the bottom water parameters (salinity, temperature and dissolved oxygen) were high due to different mixing and circulation patterns resulted by the influence of freshwater influxes from terrestrial systems. It is obvious that, the sediments of the stations that lie nearer to the coast were clayey silt, whereas stations that lie away from the shore were dominated by sand. This point reflects the influence of river water inflows into the Bay during post-monsoon. Consequently, the Bay substratum exhibited clayey-silt and organic matter rich with sediments in post-monsoon and in the stations that lie nearer to shoreline. Cociella crocodiles, Cynoglossus lida and Cynoglossus punticeps was mainly adapted to a bottom habitat feeds on polychaetes and detritus, amphipods, copepods and small molluscans [41]. In Nizampatnbam Bay, the abundance of infaunal benthic organisms was higher during post-monsoon than pre monsoon. These infaunal benthic organisms of Nizampatnam Bay were dominated by amphipods and polychaetes [40]. The terrestrial organic matter by land drainage and river runoff could contribute significantly to the overall load of organic matter [42-44]. Several workers documented that the relationship between the grain size and sediment organic content showed a negative correlation [45-47]. These organic matter enriched sediments favoured the survival of infaunal which inturn favoured the survival of Cociella crocodilus, Cynoglossus lida, Cynoglossus punticeps and Astroscopus zephyreus during post-monsoon. These four fishes can also tolerate wide ranges of fluctuations in bottom hydrography as all these four fishes were habituated to survive in marine and brackish water [48]. Hence, from the above findings, it is clearly evident that differences in the distribution of benthic fish assemblages in Nizampatnam Bay were influenced by monsoonal changes in the salinity of bottom water and sediment morphology. Monte Carlo permutation tests confirmed the significant association (p<0.05) between environmental variables and the benthic fish species distribution off Nizampatnam Bay, Bay of Bengal.

Acknowledgement

This work was carried out with financial assistance provided by Ministry of Earth Sciences, India (F.No. DOD/MOES /11-MRDF/1/31/P/05). We are grateful to OASTC, Cochin for coordinating the Project. The authors were thankful to Dr. G. Padmavathi for sharing her knowledge in the taxonomy of fishes.

References

- Peres JM (1982) General features of organic assemblages in pelagic and benthal. Marine Biology 5 (1): 119-186.

- Maria VM, Moranta J, Jenkins SR, Hiddink JG, Hinz H (2012) Effect of prey abundance and size on the distribution of demersal fishes. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 69(1): 191-200.

- Labropoulou M, Papaconstantinou C (2004) Community structure and diversity of demersal fish assemblages: the role of fishery. Scientia Marina 68(S1): 215-226.

- Candace AO, Scott WN (1973) The demersal fish of Narragansett Bay: An analysis of community structure, distribution and abundance. Estuarine Coastal and Marine Science 1(4): 361-378.

- Iglesias J (1981) Spatial and temporal changes in the demersal fish community of the Ria de Arosa (NW Spain). Marine Biology 65(2): 199208.

- Sousa P, Azevedo M, Gomes MC (2005) Demersal assemblages off Portugal: Mapping, seasonal, and temporal patterns. Fisheries Research 75(1-3): 120-137.

- Norcross BL, Holladay BA, Busby MS, Mier KL (2010) Demersal and larval fish assemblages in the Chukchi Sea. Deep-Sea Research II 57(1- 2): 57-70.

- Mecklenburg CM, M0ller PR, Steinke B (2011) Biodiversity of arctic marine fishes: taxonomy and zoogeography. Marine Biodiversity 41(1): 109-140.

- Johannesen E, H0ines AS, Dolgov AV, Fossheim M (2012) Demersal Fish Assemblages and Spatial Diversity Patterns in the Arctic-Atlantic Transition Zone in the Barents Sea. PLoS ONE 7(4): e34924.

- Buchheister A, Christopher F, Bonzek JG, Robert JL (2013) Patterns and drivers of the demersal fish community of Chesapeake Bay. Marine Ecology Progress Series 481:161-180.

- Clark TA (1972) Collections and submarine observations of deep benthic fishes and decapod crustacea in Hawaii. Pacific Sciences 26: 310-317.

- Al Daham NK, Yousif AY (1990) Composition, seasonality and abundance of fishes in the Shatt Al-Basrah Canal, an estuary in Southern Iraq. Estuarine. Coastal and Shelf Science 31(4): 411-421.

- Chave EH, Mundy BC (1994) Deep-sea benthic fish of the Hawaiian Archipelago, Cross Seamount, and Johnston Atoll. Pacific Sciences 48(4): 367-409.

- Philip C, Heemstra KH, Hans F, Malcolm JS, Jurgen S (2006) Fishes of the deep demersal habitat at Ngazidja (Grand Comoro) Island, Western Indian Ocean. South African Journal of Science 102(9-10): 44-460.

- Sankamarayanan VN, Qasim SZ (1969) The influence of some hydrographic factors on the fisheries of the Cochin area. Bulletin of National Institute of Science of India 38: 846-853.

- Bapat SV, Radhakrishnan N, Kartha KNR (1972) A survey of the trawl fish resources off Karwar, India. Proceedings of the Indo-Pactfic Fisheries Council 13(3): 354-383.

- Prabhu MS, Dhawan RM (1974) Marine fisheries resource on the 20m and 40m region off the Goa coast. Indian Journal of Fisheries 21: 40-53.

- Ansari ZA, Chatterji A, Ingole BS, Sreepada RA, Rivonkar CU, et al. (1995) Estuarine. Coastal and Marine Science 41: 593-610.

- Vivekanandan E (2011) Demersal Fisheries of India. In: Vivekanandan E (Ed.), Demersal Fisheries of India. Handbook of Fisheries and Aquaculture. Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi, India, pp. 90-105.

- Radhakrishanan N (1974) Demersal fisheries of Vizhingam. Indian Journal of Fisheries 21(1): 29-39.

- Murty V, Sriramachandra (1989) Mixed fisheries assessment with reference to five important demersal fish species by shrimp trawlers at Kakinada. In: Murty V, Sriramachandra (Eds.), Contributions to tropical fish stock assessment in India, pp. 2-28.

- Sathianandan TV, Jayasankar J (2009) Simulation Model for elevating the response of management options on the demersal fish resources of Tamil Nadu coast. Asian Fisheries Science 22(2): 681-690

- Day F (1978) The fishes of India. Williams and Sons, ltd, London, UK.

- Smith MM, Heemastra PC (1986) Smiths' Sea Fishes. In: Smith MM, Heemastra PC (Eds.), Smiths' Sea Fishes. Spinger Verlag, New York, p. 1047.

- Day F (1994) The fishes of India: Being a Natural History of the Fishes Known to Inhabit the Seas and Fresh Waters of India, Burma, and Ceylon. Fourth Indian Reprint. Volume I and II. 1047 pp.

- Fischer W, Bianchi G (1984) FAO species identification sheets for fishery purposes. Western Indian Ocean (Fishing Area 51). Prepared and printed with the support of the Danish International Develoμment Agency (DANIDA). Rome, Italy, pp. 1-6.

- Clarke KR, Warwick RM (2001) A further biodiversity index applicable to species lists: Variation in taxonomic distinctness. Marine Ecology Progress Series 216: 265-278.

- Clarke KR, Warwick RM (1994) Similarity-based testing for community pattern: the two-way lay out with no replication. Marine Biology 118(1): 167-176.

- Ter Braak CJF, Smilauer P (2002) CANOCO reference manual and user's guide to Canoco for Windows: software for canonical community ordination (version 4.53). Microcomputer power, Ithaca, NY.

- Gray JS, Christie H (1983) Predicting long-term changes in marine benthic communities. Marine Ecology progress Series 13: 87-94.

- Srinivasa Rao M, Vijaya Bhanu CH, Annapurna C, Sastry DRK, Srinivasa Rao D (2009) Echinoderms of nizampatnam bay, east coast of India. Journal of Bombay Natural History Society 106(1): 30-38.

- Buchanan JB (1958) The bottom fauna across the continental shelf off Accra, Ghana (Gold Coast). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 130(1): 1-56.

- Longhurst AR (1958) An ecological survey of the West African marine benthos. In: Longhurst AR(Ed.), An ecological survey of the West African marine benthos. Fishery Publications, Great Britan Colonial Office 11: 1-102.

- Desai BN, Kutty MK (1967) Studies on the benthic fauna of Cochin backwaters. Proceeding of the Indian Academy of Sciences 66(4) : 123142.

- Day JH (1981) The estuarine fauna. In: Day JH (Ed.), Estuarine Ecology with Particular Reference to Southern Africa, 41. AA Balkema, Rotterdam, Europe, pp. 147-178.

- Alongi DM, Christoffersen P (1992) Benthic infauna and organism sediment relations in a shallow, tropical coastal area: influence of outwelled mangrove detritus and physical disturbance. Marine Ecology Progress Series 81: 229-245.

- Alongi DM, Sasekumar A (1992) Benthic communities. In: Robertson AI, Alongi DM (Eds.), Tropical Mangrove Ecosystems. Coastal and Estuarine Studies no. 41. American Geophysical Union, US, p. 329.

- Robertson AI, Blaber SJM (1992) Plankton, epibenthos and fish communities. In: Robertson AI, Alongi DM (Eds.), Tropical Mangrove Ecosystems. Coastal and Estuarine Studies no. 41. American Geophysical Union, US, p. 329.

- Narayanaswamy BE, Nickell TD, Gage JD (2003) Appropriate levels of taxonomic discrimination in deep-sea sediments: species vs. family Marine Ecology Progress Series 257: 59-68.

- Srinivasa Rao M (2011) Macrobenthic Diversity and Community Structure of Nizampatnam Bay, Bay of Bengal. Thesis submitted to Andhra University, India, p. 246.

- Jeyaseelan MJP (1998) Manual of fish eggs and larvae from Asian mangrove waters. In: Jeyaseelan MJP (Ed.), Manual of fish eggs and larvae from Asian mangrove waters. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris, p.193.

- Ittekkot V, Safiullah S, Mycke B, Seifert R (1985) Seasonal variability and geochemical significance of organic matter in the River Ganges, Bangladesh. Nature 317: 800-802.

- Alongi DM, Christoffersen P, Tirenti F, Robertson AI (1992) The influence of freshwater and material export on sedimentary facies and benthic processes within the Fly delta and adjacent Gulf of Papua (Papua New Guinea). Continental Shelf Research 12(2-3): 287-326.

- Robertson AI, Alongi DM (1995) Role of riverine mangrove forests in organic carbon export to the tropical coastal ocean: a preliminary mass balance for the Fly Delta (Papua New Guinea). Geo-Marine Letters 15(3- 4): 134-139.

- Link AG (1967) Delineating the major depositional environments in northern part, Philip Bay, Victoria. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 37(3): 931-951.

- Setty MGAP, Nigam R (1982) Foraminiferal assemblages and organic carbon relationship in benthic marine ecosystem of western Indian continental shelf. Indian Journal of Marine Sciences 11(3): 225-232.

- Thrush SA, Townsend CR (1986) The sublittoral macrobenthic community composition of Lough Hyne, Ireland. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Sciences 23(4): 551-574.

- Kottelat M, Whitten AJ, Kartikasari SN, Wirjoatmodjo S (1993) Freshwater fishes of Western Indonesia and Sulawesi. In: Kottelat M, Whitten AJ, Kartikasari SN, Wirjoatmodjo S (Eds.), Periplus Editions, Hong Kong, China, p. 221.

- Alongi DM (1989) Ecology of soft-bottom tropical benthos: a review with emphasis on emerging concepts. Revista de Biologia Tropical 37(1): 7388.

- Alongi DM (1996) Decomposition and recycling of organic matter in muds of the Gulf of Papua, northern Coral Sea. Continental Shelf Research 15(11-12): 1319-1337.

- Gaudette HE, Wilson RF, Lois T, Folger DW (1974) An inexpensive titration method for determination of organic carbon in recent sediments. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 44(1): 249-253.

© 2018 Srinivasa MR, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)