- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Livestock Activity in Norwestern Patagonian Protected Areas

Paula Gabriela Núñez1* and Cecilia Inés Núñez2

1Universidad de Los Lagos, Universidad Nacional de Río Negro, Instituto de Investigación en Diversidad Cultutal y Procesos de Cambio, CONICET, Argentina

2Dirección Regional Patagonia Norte, Administración de Parques Nacionales, Argentina

*Corresponding author: Paula Gabriela Núñez, Universidad de Los Lagos, Universidad Nacional de Río Negro, Instituto de Investigación en Diversidad Cultutal y Procesos de Cambio, CONICET, Argentina

Submission: February 02, 2023; Published: March 30, 2023

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume10 Issue5

Case Report

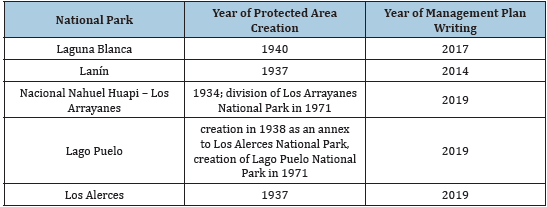

This paper presents results on how livestock and livestock activity (or cattle ranching) is perceived by the National Park Administration in the Andean region of nor western Patagonia, Argentina. Livestock activity in Argentinean Patagonian Andes has older antecedents than the establishment of National Parks. Its development and expansion is found around late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the entire Patagonian territory was incorporated into the National State of Argentina as agricultural-livestock colonies [1,2]. By then and for a few decades, open-borders policy was proposed as a strategy for economic development of Argentina and Chile [3]. A related activity, transhumance, has even older roots in Patagonia, dating back to the 16th century [4], but the network of herding roads or trails throughout the mountains had a clear expansion in this particular period, and just a few years before the creation of the firsts National Parks. Given that livestock activity precedes the creation of National Parks, we compared the way in which the ideas surrounding cattle ranching are presented in the Management Plans documents of the protected areas of northwestern (where Andes mountains are) Patagonia in Argentina (Table 1)..

Table 1: Information on dates of protected areas creation, and management plans elaboration.

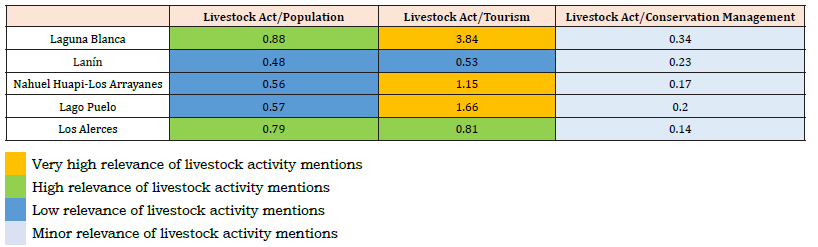

For the analysis, we first compared the number of citations of “livestock activity” with respect to citations to the idea of “population”. We also compared “livestock activity” with “tourism”, which in theory is the main activity in national parks, and with the idea of “conservation management”, for each of norwestern Patagonia National Parks. Results are summarized in the following Table 2. Results suggest that the association of “livestock activity” with the present population is strong only in the cases of Laguna Blanca and Los Alerces National Parks (in green). For the rest of the National Parks (in blue), “population” as a term, should be associated with a larger variety of activities (or pluriactivity), and with other aspects to be considered in the management of the National Park (e.g., land tenure).

Table 2:Comparison of citation.

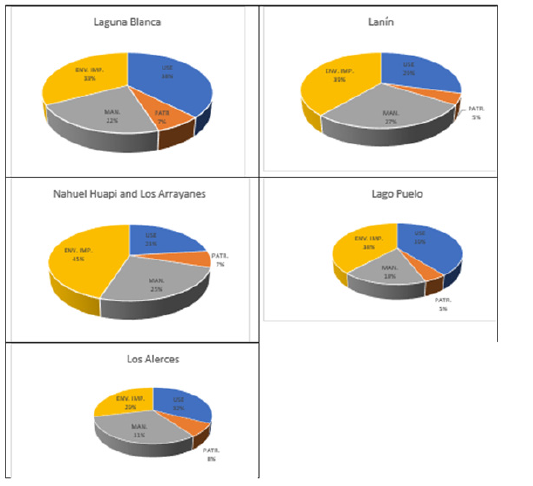

“Livestock activity” shows more references than “tourism” in all the national parks (in yellow), with the exception of Lanín (in blue) and Los Alerces (in green), where tourism is possibly more complex, or either, ranching is considered with fewer variables than in the other cases. Notions related to management and conservation are clearly higher for all National Parks (in light blue). From here, the “livestock activity” was reviewed in its context, based on a line-byline reading (Riessman, 2008). In the reading of the documents, four open codes appeared in relation to cattle ranching: use; patrimony; management; environmental impact. This means that there are four approaches or views that the National Parks Administration introduces. A use (USE) as a fact in a given space. It is linked to past use but is characterized in the present by its precariousness and informality. A patrimony (PATR.) or heritage, that understands this activity as cultural and relevant to the identity of the protected area. Management (MAN.) that must be carried out by both parts, the population and the National Parks Administration. An environmental impact (ENV. IMP.) that has only been recognized as negative, for the ecosystems than must be protected [5-9].

Figure 1:Weight of different coding for each protected area.

The following graphs (Figure 1) allow to see the weight of each

coding for each National Park. Livestock activity was built on the

destruction of many of the environments that are now part of

the analyzed protected areas, but at the same time represents an

identity recognized as intangible heritage. The analysis allowed us

to recognize some aspects to highlight:

a. Livestock activity is just one of many environmental

problems.

b. Livestock activity is not the main conservation problem

for most National Parks, with the exception of Laguna Blanca,

where is the central problem.

c. In all cases, the rural populations living in protected areas

recognize that cattle ranching is their main activity and the

source of their identity.

d. The only protected area that recognizes a change

associated with tourism is Los Alerces National Park.

e. The management and policies focus on internal aspects

of the park rather than on dialogue with other stakeholders,

with the exception of Los Alerces National Park, which does not

mention this issue.

f. Livestock is seen as an activity with high negative

environmental impact in all protected areas.

g. Livestock activity itself is seen with negative ecological

impact, as a tradition (and precarious) and is also recognized

as intangible heritage.

h. The cultural value recognized to the Mapuche culture

does not appear in the characteristics of the existing or past

use, with the exception of transhumance.

i. There is no gender perspective in management plans.

Herding trails, transhumance, appear as the heritage of a territory lived with livestock activity, installed at the end of the XIX century, but its negative environmental impact still remains in the way the activity is carried out. In all Management Plans, mangers are particularly sharp in terms to their own historical shortcomings, they seek initiatives to overcome limits and history, they recognize themselves as responsible not only for conservation but also for the redefinitions that practices need. Although not all of the Patagonian Andes range are in protected areas, the size of the biosphere reserve makes it necessary to address this issue. Change and innovation are an enormous challenge for an institution that has yet to define a clear definition of this particular activity [10].

References

- Coronato F (2010) The role of sheep farming in the construction of the territory of Patagonia. (PhD Thesis), Doctoral School ABIES, Paris TECH, France.

- Vejsbjerg L, Núñez P, Matossian B (2014) Transformation of frontier national parks into tourism sites. The north Andean Patagonia experience (1934-1955). Almatourism 5(10): 1-22.

- Méndez L, Muñoz J (2013) Sectoral alliances at a regional level. The Argentine-Chilean North Patagonia between 1895 and 1920. In: Nicoletti M, Núñez P (Eds.), Araucania-Northern Patagonia: Territoriality under debate, IIDYPCA, Bariloche, Argentina, pp. 152-167.

- Bandieri S (2020) Crossing the Andean mountain range, University of the Lakes, Chile.

- APN (2019) Lago Puelo national park management plan, National Parks Administration, National government, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- APN (2017) Laguna Blanca national park management plan, National Parks Administration, National government, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- APN (2014) Lanin national park management plan, National Parks Administration, National government, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- APN (2019) Los Alerces national park management plan, National parks administration, National government, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- APN (2017) Nahuel Huapi & Arrayanes national park management plan, National parks administration, National government, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Fortunato N (2005) The territory and its representations as a source of tourist resources. Foundational values of the “national park” concept. Studies and Perpectives in Tourism 14(4): 314-348.

© 2023 © Paula Gabriela Núñez. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)