- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Analysis of Residents’ Accessibility to Residential Housing Estates in Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

Olaseni AO1, Owolabi BO1 and Gabriel E2*

1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria

2Department of Environmental Management, Kaduna State University, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Gabriel E, Department of Environmental Management, Kaduna State University, Nigeria

Submission: October 27, 2022; Published: January 20, 2023

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume10 Issue3

Abstract

This paper analyses the residents’ accessibility to residential housing estates in Ado Ekiti Nigeria, with a view to suggesting appropriate measures to improve on it. To achieve this aim, building survey of the sampled residential public estates was obtained from Ekiti State Housing Corporation and Federal Ministry of Works and Housing, amounting to 835 housing units. A sample size of 32% constituting 267 of the total housing units in the study area was taken for this study. Therefore, 267 copies of questionnaire were administered and retrieved from household heads using systematic sampling technique. Findings revealed that easy accessibility was the principal factor for the choice of residential estates; accessibility based on income, attributed 43.8% to fairly accessible; accessibility based on road network submitted that 29.2% of the roads leading to the residential estates were in good condition; and political interference in accessibility to ownership of any building in the estates accounted for 86.3% among others. The paper recommends corporate interest of the low-income class in future housing program in this locale through low-cost housing as well as granting housing loans with flexible means of repayment to public servant to guarantee easy accessibility to public housing in the study area. The study furthermore advocated comprehensive survey on types of housing provision to reflect the social and cultural needs of the people not leaving behind comprehensive infrastructure provision as well as increasing subventions of institutions of government responsible for housing provision to stimulate their productivity and efficient service delivery.

Keywords:Residents; Accessibility; Residential housing; Estate; Infrastructure

Introduction

Housing is seen as one of the most important things for the physical survival of man after the provision of food. It contributes to the physical and moral health of a nation and stimulates the social stability, the work efficiency and the development of the individuals. In spite of these facts there is no doubt that housing in quantitative terms is still a major problem facing the Nigerian urbanities and governments beside the characteristic slums and conditions it is becoming increasingly difficult for average Nigerians to own houses [1]. One of the major responses to the housing challenge has been Public housing. Housing estates refers to a form of housing provision, which emphasizes the role of private organizations and government in helping to provide housing, particularly for poor, low-income and more vulnerable groups in the society [2]. The ever-mounting crisis in the housing sector of the developing world has various dimensions, which range from absolute housing unit shortages to the emergence and proliferation of the slums/squatter settlements, rising cost of housing rent, and the growing inability of the average citizen to own their own houses or procure decent accommodation of their taste in the housing market [3]. Accessibility has been described as the potential of opportunities for interaction [4]. It is the extent to which a person, at a given place and time, has the ability to access opportunities that they want or need to access.

A study by Onibokun AG [5] estimated that the nation’s housing needs for 1990 to be 8,413,980; 7,770,005 and 7,624,230 units for the high, medium, and low-income groups, respectively. The same study projected the year 2000 needs to be 14,372,900; 13,273,291 and 12,419,068, while the estimates for the year 2020 stands at 39,989,286; 33,570,900; and 28,548,633 housing units for high, medium and low-income groups, respectively [6]. Again, the national rolling plan from 1990 to 1992 estimated the housing deficit to increase between 4.8 million to 5.9 million by 2000. The 1991 housing policy estimated that 700,000 housing units needed to be built each year if the housing deficit was to be cancelled. The document, indeed, indicated that no fewer than 60 percent of new housing units were to be built in the urban centres [7-9]. This Figure 1 had increased at the time the 1991 housing policy was being reviewed in 2002. In 2006, the Minister of Housing and Urban Development declared at a public symposium on housing, that the country needed about ten million housing units before all Nigerians could be sheltered. Another estimate in 2007 by the president put the national housing deficit at between 8 and 10 million [10].

Figure 1: Locational map of public estates in Ado-Ekiti. Source: Google imagery (2022).

Furthermore, individual cannot own houses of their own as a result of the high construction cost involved, it has contributed to people hiring at very exorbitant rates because there are more buyers of housing goods than the supply of those goods and services [11]. This effect of housing shortage mostly predominately in urban areas like Lagos not only led to overcrowding in several cities, but it has also led to many taking shelter under the bridges, shacks and make shifts [11]. The most unfortunate thing is that the existing residential buildings are not suitable for modern needs and lack facilities such as Water Closets (WCs), Pipe-borne water, power supply, open spaces among others, and the situation prompted the United Nations to launch the aggressive program of shelter for all in the year 2000 [11].

The Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria (FMBN), which is answerable for the provision of mortgages to low-income earners through the National Housing Trust Fund (NHTF), has operational and financial capability restraints that limit its efficiency [12]. With this, few low-income earners who own their houses usually obtain land and build incrementally with their funds, while the high-income house-owners buy with money or mortgage finance, usually pay back over a maximum period of 10 years [13].

Going by the aforementioned studies, it was evidently revealed that there is a gross shortage of housing facilities in Nigeria. Therefore, on this background, this paper examined residents’ accessibility to residential housing estates in Ado Ekiti Nigeria, with a view to suggesting appropriate measures to improve on the present situation. In the light of this, the study, among others examined some variables that made the estates attractive; accessibility to these public estates based on income classification; accessibility to these public estates based on road network; conditions required for accessing the estates; and the reasons why accessing public residential estates is cumbersome in the study area.

Statement of the research problem

In spite of the fundamental role of housing in the life of every individual and the nation, and the United Nations’ realization of the need to globally attain adequate shelter for all, the housing crisis remains one of the global problems and a grave and rising challenge facing both urban and rural residents, particularly in most developing countries. It is generally estimated that the world needs to house an additional 68 million to 80 million people [14]. According to the United Nations Population Fund, world population passed 6.1 billion in 2001 and it is expected to reach between 7.9 and 10.9 billion by 2050 (Wikipedia, 2003). Over 90% of the growth is forecast to occur in the developing countries by year 2026. Those estimates represent a formidable housing challenge. The situation even becomes more serious and worrisome when one realizes the fact that despite a number of political, social, and religious initiatives taken in the past in some of these developing countries, a large proportion of their population still lives in sub-standard and poor housing and in deplorable and unsanitary residential environments [1].

Owolabi BO [15] indicated that there was overcrowding of houses and over-utilization of basic infrastructural facilities and utilities provided in most houses. The demand for houses are more than the houses available and the housing conditions are getting worse and worse every day as a result of increase in the population. However, studies on housing situation in Nigeria especially in the urban areas have revealed shortage in housing stock expressed in both qualitative and quantitative terms [5,16-19]. This was as a result of rapid urbanization and poor economic growth. It has been noted that the existing housing stocks are inadequate to cater for the increasing population of our urban centres (Jiboye, 1997). Alufohai AJ [19] also revealed that Nigeria needs about 17.5 million units of housing to close the existing gap between the demand and supply of residential dwellings in Nigeria. Meanwhile, high rate of population growth, inflated real estate values, deplorable urban services and infrastructure and a lack of implementation of planning laws have been found to complicate the housing problem [20].

Housing delivery in Nigeria is provided by either the government or private sector, but despite federal government access to factors of housing production, the country could at best expect 4.2% of the annual requirement [21]. Substantial contribution is expected from other public and private sectors. It should be acknowledged that private sector developers account for most of urban housing [21]. The production of housing in Nigeria is primarily the function of the private market; approximately 90% of urban housing is produced by private developers. This is due to housing demand created by rural-urban migration, which account for 65% of urban population growth, the fixed supply of urban land, and inflation of rental and housing ownership cost [22]. Unfortunately, the private sector is saddled with numerous problems which make supply always fall short of demand and lower production quality [23].

The problem of qualitative housing has been a concern for both the government and individuals. Appreciating these problems, both public and private sector developers make effort through various activities to bridge the gap between housing supply and demand, but the cost of building materials, deficiency of housing finance arrangement, stringent loan conditions from mortgage banks, government policies among other problems have affected housing delivery significantly in Nigeria [24-26]. Therefore, the problems addressed focused on attractiveness of the estates; accessibility to these public estates based on income classification; accessibility to these public estates based on road network; conditions required for accessing the estates; and the reasons why owning any of the buildings in these estates is difficult, in the study area.

Study area

Ado-Ekiti is the capital of Ekiti State, Nigeria and the administrative headquarters of Ado Local Government Area. Since the creation of the State on October 1st, 1996; Ado-Ekiti has witnessed rapid population growth and urban expansion. The city had a total population of 545,447 in 2019 as projected from 2006 National Population Census [27]. This has contributed to the rapid changes and the deterioration in the physical environment of the city. The land rises northwards and westwards from 335 meters in Southeast and attains a maximum elevation of about 455 meters in the Southwest [11]. The low relief and gentle gradient characteristics of the region favors agriculture and construction activities, which enhance the growth of the city. It is located between latitude 7°37′16″ North and longitude 5°13′17″ East. The city is bounded in the north by Irepodun/Ifelodun Local Government, and Gbonyin Local government to the East, in the South and West by Ekiti South- West, Ikere, and Ise-Orun Local Government Areas, with a plan metric area of about 293km2 [28].

The area under study falls within the tropical climate with two distinct seasons, that is, the wet and dry seasons. The wet season comes with the tropical maritime air mass originating from the Atlantic Ocean between the month of April and October, while the dry weather is usually brought by the tropical continental air mass blowing in from the northern Sahara, between November and March. The average total rainfall per year in the study area is put at 450mm giving an average monthly rainfall of 121mm. There is a sharp fall in rainfall between the month of July and August. The temperature of the area is high throughout the year with a mean monthly temperature 27 °C and a range of 37 °C between the month of February and the Month of August

Ado-Ekiti doubles as a local government and state headquarters is a one town local government with some farm settlements such as Ureje, Ilamao, Isoaye, Ago Aduloju, Emirin, Aso, Igirigri, Ilokun, Temidire, Omiolori to mention few. The landscape of Ado-ekiti is dotted with rounded and steep sided hills of volcanic origin such as the Ayoba hill which accommodates the state government house. Greatly undulating slopes forms the sources of streams such as Amu, Awedele, Omiolori, Ajilosun, Ureje among others. The study area further enjoys the privilege of been a nodal town located at the centre of the state hence a road that leads to other part of the state converge at Ado-Ekiti. The whole of Ado-Ekiti is underlain with the basement of major rocks identified and undifferentiated igneous and laterites with white sands which abound in the area. The area is also endowed with forest resources of all sorts which include wildlife, hard wood such as iroko, obeche, mahogany, and afara. Also, the federal and state government has established forest reserves at various points to reduce the effect of forest resource depletion. The land use of the study area is characterized by compact development of residential zones, with gentrification gradually setting in along the corridors of the major roads. Other land uses also include commercial, industrial, and recreational such as Fajuyi pack, among others.

Ado-ekiti local government is divided into 13 political wards in the ward creation by the federal government. Twelve out of the thirteen wards are within the city while the thirteenth ward is accommodating all the farm settlements. The study area is blessed with both skilled semi-skilled and unskilled manpower, middle and high-level manpower at the Federal Polytechnic, Ekiti State University, Afe Babalola University and the several primary institutions within the city. It also serves home for federal and state government agencies. Ado-Ekiti is traditionally headed by an Oba with the title as “Ewi of Ado” and supported by the Ewi-in-Council, which comprises of several chiefs and Bales of the various quarters and farm settlements. However, the Ewi is the only recognized paramount ruler of the study area.

Methodology

This study involves a large population of occupants of public residential housing estates in Ado Ekiti. Data was collected on residents’ accessibility to residential housing estates in Ado Ekiti through a well-structured questionnaire and interview in accordance with the focus of the study. Since there is no exact population figure for the residents of the various residential housing estates, therefore the population for this study was estimated as: Total population=Total no of housing units in all the residential estates x Average Household size; that is, 835 x 5= 4175. According to figure given by Ekiti State Housing Corporation and Federal Ministry of Works and Housing (2018), there were 835 housing units in the study area and national average household size as given by the National Population Commission and ICF International (2014) is 5 persons per household. Therefore, the target population for this study is 4175. However, the sampling frame for this study comprises of the 6 public housing estates in Ado Ekiti, which include Fajuyi Estate, Obasanjo Estate, Bawa Estate, Fayose Estate, Federal housing Estate and Okeila housing estate (making up the 835 housing units). The study made use of simple random sampling technique with replacement across the public housing estates to administer questionnaire in the study area.

In addition, in order to have a reliable and manageable representation of the sample frame, the sample size of 32% of the 835 housing units was considered. The justification for the choice of 32% as sample size for this study is informed by Amugune (2014) who opined that the less (more homogeneous) a population the smaller the sample size. Therefore, based on this justification, 32% sample size was used for this study and amounted to 267 copies of questionnaire which were administered to the respondents. This proportion is considered ideal and reasonable because no fixed percentage is ideal; rather, sample size is determined by the circumstances surrounding the study situation (Ojo, 2005). However, the research findings were presented, interpreted and discussed through SPSS version 25 and Microsoft Excel 2013.

Results and Discussion

This section examines the residents’ accessibility to residential housing estates in the study area. Therefore, Tables 1 to 5 presents the descriptive analysis of residents’ accessibility to residential housing estates in Ado Ekiti, Nigeria. The results are shown in the following tables and discussed as presented.

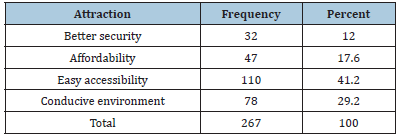

Table 1:Attractions to the estates.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

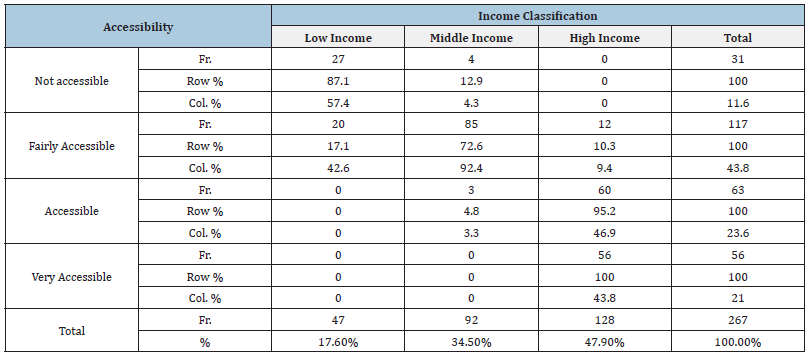

Table 2:Cross tabulation of accessibility metrics based on income classification.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

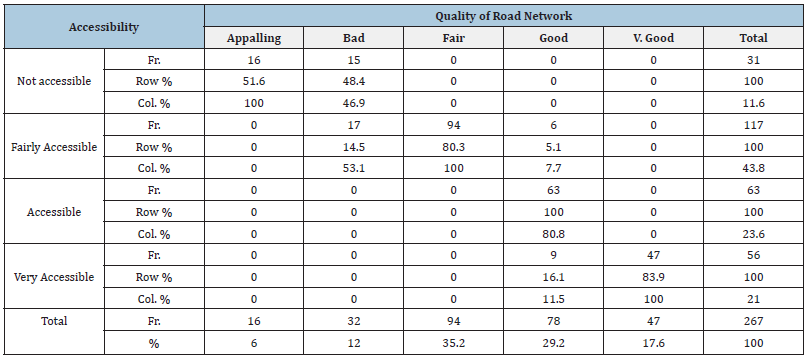

Table 3:Public estates accessibility based on quality of road network.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

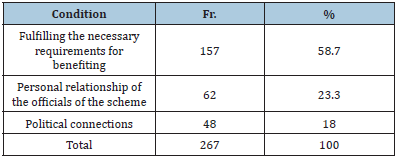

Table 4:Conditions required accessing the estates.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

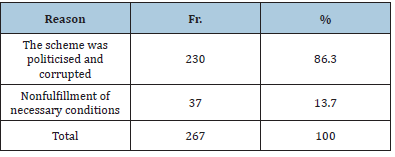

Table 5:Reasons of not accessing the estates.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

Attractions to the estate

The statistics in Table 1 show that most of the respondents asserted that easy accessibility is the principal attractive factor, which enhanced their choice of these estates as residential abode. It was gathered that most of the estates were adequately accessible to the efficient public transport network in Ado - Ekiti. At the time of survey, four out of the six estates investigated enjoyed good accessibility from their abutting asphalt tarred major roads. The socio-economic attributes of the inhabitants reflect in the serenity and neatness of the residential estates. The educational exploits of majority of the residents furnished them with the appropriate tools to arrange and maintain habitable residential environment with high degree of hospitability.

Assessment of public estates accessibility based on income classification

The results of this study revealed that these estates are accessible to the people. As depicted in Table 2, a less significant percentage (11.6%) of the respondents submitted that these estates were not accessible to the public. This indicates that most respondents believed these estates have enjoyed easy and adequate accessibility from the public. It is worthy to note that 17.6% of respondents interviewed were low-income earners despite significant proportion of the estates investigated were low-cost housing scheme. This shows that the original concept and intention of the government to provide habitable public housing estates to the people in urban poverty has been negated and defiled. Aside rapid urbanization of poverty, this has been a contributing factor to the ever-increasing housing deficit in Nigerian urban areas. From economic standpoint, these estates are not affordable and accessible to low-income earners. This unwholesome scenario started at the inception of these estates when the house prices of 1-bedroom apartment in Federal housing estate was pegged at N6000 and the 3-bedroom unit with selling price of N15000. This is despite the low-income earners then were being paid N2772 per annum [29].

This wide gap between income and housing prices screened them out of the opportunity to access the estate. This trend has been sustained until the time of survey. It was discovered that the rental value of 3-bedroom bungalow in Fajuyi estate was in the range of N150000 to N200000 while the duplex rental value was between N250000 and N300000. These figures indicate that these estates were built for other income classes aside the low-income earners in a State that is yet to fully implement the new minimum wage of N30000 after a year of its existence. Corroborating these viewpoints, 57.4% of low-income respondents avouched that these estates were not accessible. In addition, about 87.1% of respondents who reported that these estates were not accessible were lowincome earners. Further query to establish this submission revealed that majority of these low-income earners were squatters in these residential estates. Their financial incapability wrestled away their opportunities to seek public residential housing estates. Glaringly, these estates were accessible to the middle and highincome earners. Given that, 92.5% of respondents who reported these estates as accessible were middle-income earners, and all the respondents who tick the box of very accessible were high-income earners. The thoughts of the low-income earners were laced with palpable emotional attachment of marginalization and deprivation. They bemoaned that both state and federal governments are not building housing units again, but rather selling off undeveloped lands within the estate to their cronies. One respondent bequeathed with stout courage lambasted the current administration for not selling the undeveloped plots of land directly to the public but to friends, which would resell the plots of land to the prospective developers on profit making basis, which invariably were too expensive for low-income earners in the study area.

Assessment of public estates accessibility based on quality of road network

This study used the quality of roads leading to the various estates as a proxy to assess the locational-based accessibility of the public housing estates examined. The results in Table 3 show that 35.2% of respondents submitted that the roads leading to the estates were fair in condition. Whilst 16% of respondents posited that road network was bad, about 29.2% admitted that the road network abutting the estates were in good condition. This study further reveals that all respondents who attested that the road network were in bad condition, also submitted that the estates were not accessible from locational standpoint because of the inefficient road network leading to the estates. These sets of respondents admitted that the few of estates were located at outskirts of the city, which in turn reduces the opportunity of people who are not car owners to live in the estates. This locational demerit was also attributed to influence the reduction of proximity to where the few jobs in the cities are located especially for low-income earners. These respondents claimed some of the roads leading to the estates were in poor conditions thereby making vehicular movement back and forth of the estates a herculean task.

Judging from this study, when the road network that connects public residential estates to other parts of mid-sized cities in Nigeria such as Ado-Ekiti are bad, the accessibility index of such estates tends to reduce. Accessibility of public estates relates positively with the conditions of road connecting them to other parts of the city where they are domiciled. This study reveals that over 80% of respondents that admitted that these estates were fairly accessible also believed the road conditions were fair. In this connection, all the respondents who claimed the estates were accessible also believed the road conditions were good. Similarly, over 80% of respondents who admitted the estates were very accessible also believed the road conditions were very good. In this line, all the respondents that submitted that road conditions were good rated the accessibility of estates high. It is glaring from this study that when the roads connecting public residential estates to other landuses are tarred and well maintained, with efficient and effective public transport system, it will increase the propensity of people to seek habitation in public residential estates without giving greater emphasis to distance, cost and time.

Conditions required accessing the estates

This study further examines the conditions required to adequately access the public residential estates. The result in Table 4 shows that more than half of the respondents (58.7%) submitted that the fulfillment of necessary requirements was vital to accessing the estates. The process of acquisition entails the collection of form from the appropriate government agency; make payment to the appropriate bank account, and then allocation after tendering of the bank receipt, which shows that prospective homeowner, has paid the required fees to the bank. About 18% of respondents were disappointed that the principal condition to access the public residential estates was that a person should be in the caucus of a leading politician in the state. It is a common say in Nigeria that political influence is the vital ingredient when accessing public structure. In a country like Nigeria marked with rotten and self-serving politics, there is iota of truth that political connection dictates to a considerable extent, people’s accessibility to public housing.

Reasons for not accessing the estates

Further query to know the reasons that act as barrier to public housing accessibility in the study area reveals that political interference (accounted for 86.3%) was the major element that limits people’s accessibility to public residential estates. The politicians were apt in interrupting the official process of housing and land acquisition in the estates. Whether you are financial capable to acquire a property in the estate or otherwise, everyone faces the same fate of backdoor acquisition using the power of their political benefactor. The unwholesome situation becomes problematic when politicians acquire the housing units and sell out to people on profit making basis. This arrangement schemed out the low-income earners from accessing the public residential estates, since the housing units moved into the hands of the highest bidder.

Conclusion

It has been established by scholars in the built environment that housing is one of the basic necessities of life ranking third after food and clothing. Thus, its accessibility commands high sense of prominence along every line of thought by government and the governed in every contemporary society. However, results obtained from this study pointed to the truth that all is not totally well when it comes to residents’ accessibility to residential housing estates in Ado Ekiti. It is heartsick to note that the low-income class living in this area who are in dearth need of housing units to meet their changing housing need are financially incapacitated by the exorbitant prices of these housing stocks thereby creating a need gap in housing in this area. The fate of these set of inhabitants is even worsened by their present housing condition and its aesthetic values owing to haphazard housing transformation. To further compound, the aforementioned many headed challenges; institutions of government entrusted by law to fix housing problems in the study area had virtually abandoned their primary mandate due to diverse systemic burdens. This is made manifest in the area of inadequate and poor infrastructural facilities to stimulate housing satisfaction, which is an antidote of housing need.

Recommendations

The results obtained in this study have policy implications for public housing provision in Ado Ekiti, Nigeria. The recommendations were put forward to address and redress residents’ accessibility in public residential estates in Ado Ekiti and other cities with similar housing attributes in Nigeria. Public housing accessibility was calibrated using the income classes of residents and quality of road network as proxy variables to perform economic and locationbased examination of public housing accessibility. It is crystal clear that aside low-income earners, other classes of income earners have adequate access to the public residential estates under study; nevertheless, most of these estates were low-cost housing estates. Similarly, this study shows that accessibility relates positively with the quality of road network leading to the estates. Estates that were connected to efficient road network enjoyed better accessibility compared to estates with appalling road network, which connect them to other parts of the city. Given the social responsibility of government in the provision of public housing, it is best place to ensure there is equitable access to public housing by all income classes.

This study recommends that future housing programmes should consider emphatically the interest of the low-income earners. Houses intended for low-income earners should be strictly allocated to them. The low-cost housing segment of future housing programmes should be structured in a manner that rent arrangements will bring about owner-occupier status of the buildings over a long period. This has been proving to be effective way to improve public access to residential estates by private sectors in Lagos and other parts of the country. This study also recommends that state government should give housing loans to public servants with flexible repayment conditions, which will enhance their access to public housing in Ado Ekiti. On this note, this study suggests that developers should ensure that future properties should reflect massive building aesthetic value, which would enhance housing satisfaction and minimize informal transformation of houses, which was rampant in the study area. In addition, this study shows that both federal and state governments have provided over 800 housing units in the six residential estates in Ado Ekiti in the last 30 years.

References

- Oladapo AA (2006) A study on tenant’s maintenance awareness, responsibility and satisfaction in institutional housing in Nigeria. International Journal of Strategic Property Management 10(4): 217-231.

- Van Vliet W (1990) International handbook of housing policies and practices. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, USA.

- Ademiluyi AI, Raji BA (2008) Public and private developers as agents in urban housing delivery in Sub-Saharan Africa: The situation in Lagos State. Humanity & Social Sciences Journal 3(2): 143-150.

- Grace R, Saberi M (2018) The value of accessibility in residential property. Australasian Transport Research Forum 2018 Proceedings, Darwin, Australia, pp. 1-17.

- Onibokun AG (1985) Housing in Nigeria, Nigerian Institute for Social and Economic Research (NISER), Ibadan, Nigeria.

- Agbola T (1998) The housing of Nigerian: A review of policy development and implementation. Research Report No. 14, Development Policy Centre, Ibadan, Nigeria.

- Ogu VI (2002) Urban residential satisfaction and the planning implications in a developing world context: The example of Benin city, Nigeria. International Planning Studies 7(1): 37-53.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria (1991) National housing policy, Federal Ministry of Works and Housing, Lagos, Nigeria.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria (1991) National housing policy. Federal Government Press, Lagos, Nigeria.

- Yar’adua UM (2007) Presidential address at the 2nd international seminar on emerging urban Africa. Yar’adua Conference Centre, Abuja, Nigeria.

- Adebayo AA (2005) Sustainable construction in Africa. Agenda 21 positional paper.

- Pison Housing Company (2010) Overview of the housing finance sector in Nigeria. Commissioned by EFInA and FinMark, Finmark Trust 1: 15-20.

- Enuenwosu CE (1985) The federal mortgage bank of Nigeria: Its objectives and future prospects. Central Bank of Nigeria Bullion, pp. 20-25.

- Awake (2005) The global housing crisis: Is there a solution? Monthly Publication of Jehovah Witness, pp. 3-12.

- Owolabi BO (2017) Effect of housing condition and environmental sanitation on the residents of Oyo State, Nigeria. International Journal of Research in Environmental Science 3(3): 17.

- Abiodun JO (1983) Housing problems in Nigerian cities. Third World Planning Review 5(3): 339-347.

- Aribigbola A (2008) Housing policy formulation in developing countries: Evidence of programme implementation from Akure, Ondo State Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology 23(2): 125-134.

- Mabogunje A (2002) Housing delivery problems in Nigeria. Punch Newspaper, Lagos, Nigeria.

- Alufohai AJ (2013) The Lagos state 2010 mortgage law (Lagos HOMS) and the supply of housing. FIG Working Week, Abuja Nigeria.

- Olotuah AO (2000) The challenge of housing in Nigeria. In: Akinbamijo OB, Fawehinmi AS, Ogunsemi DR, Olotuah A (Eds.), Effective Housing in the 21st Century Nigeria, The Environmental Forum, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria, pp. 16-21.

- Federal Office of Statistics (1983) Social statistics in Nigeria, Lagos, Nigeria.

- Taylor R (2000) Urban development policies in Nigeria.

- Nubi OT (2008) Affordable housing delivery in Nigeria: The South African foundation International conference and exhibition Cape Town, pp.1-18.

- Raji O (2008) Public and private developers as agents in urban housing delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: The situation in Lagos State. Humanity of Social Sciences Journal 3(2): 143-150.

- Bichi K (1997) Ensuring the success of national housing fund. Business Times 1(13): 14.

- Daramola SA (2004) Private public participation in housing delivery in Nigeria, paper presented at a business luncheon organised the Royal Institute of Surveyors (RIS) in Chinese restaurant, Lagos, Nigeria.

- National Population Commission (2006) Population and housing census: Population distribution by Sex, State, LGA, and Senatorial district.

- Ebisemiju FS (1989) Analysis of drainage basin and similar parameter in relation to soil and vegetation characteristic. Nig Geog Journal 1(2): 37-44.

- Olotuah AO (2015) Assessing the impact of users’ needs on housing quality in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. Global Journal of Research and Review 2(4): 100-106.

© 2023 © Gabriel E. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)