- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Perception of People to the Establishment of Protected Areas in Some Local Communities of the Niger Delta, Nigeria

Aroloye O Numbere*, Tambeke N Gbarakoro and Eberechukwu M Maduike

Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Aroloye O Numbere, Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, Choba, Nigeria

Submission: December 11, 2021; Published: March 31, 2022

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume9 Issue5

Abstract

Protection of forest is a conservation strategy to save biodiversity from extinction from the activities of humans. However, in many communities there is an active resistance against the establishment of protected areas aimed at taking away land which is a major source of survival for the local people. This study distributed 100 (n=100) structured questionnaires each in three georeferenced communities namely Okrika, Buguma and Bori. The aim was to find out whether the establishment of protected areas (parks) in the communities was bad for the people amongst other questions. The number of responses for the various questions were analyzed statistically with an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Most of the results were significant at p<0.05 and shows that fishing (21.0±1.0-64±1.0) was the most dominant occupation while hunting was the least (1.5±0.5-18.0±1.0). People over exploit environmental resources because they need the resource for commercial (33±1.0-69±1.0) and subsistence (1.5±0.5-66.5±0.5) purposes. Many interviewed suggested that jobs (22.0±1.0-34.5±0.5) and the promulgation of laws (51.0±1.0-69.0±1.0) are two key tools to be used to stop the over exploitation of natural resources. Lastly, the establishment of protected areas was accepted by majority who answered yes (63.0±1.0-91.0±1.0) as compared to those who answered no (7.5±0.5-36.5±0.5). These results imply that the people are highly dependent on their natural resources for survival. They therefore need an alternative way to make ends meet in other to facilitate the protection of their environment.

Keywords: Local communities; Nigeria; Environment; Conservation biology; Soil formation; Waste disposal

Abbreviations: IUCN: International Union for the Conservation of Nature; UNEP: United Nations Environmental Program; WWF: World Wide Fund; CRNP: Cross River National Park; ANOVA: Analysis of Variance

Introduction

Biodiversity includes a lot of species found all over the world and is significant towards the existence of humanity that is why its preservation is a major priority in conservation biology [1,2]. Some benefits of biodiversity include provision of food, drugs, and medicine [3]. Ecological benefits include soil formation, waste disposal and purification, nutrient cycling, and solar energy management [4]. It is estimated that the total value of these ecological services is at least $33 trillion per year [5], which is more than double the GNP of all the countries put together in the world. Ecological activities depend on billions of years of evolution, which is at no cost to huma beings. Ten species get extinct annually from natural causes, but because of human activities it is feared this rate will be multiplied up to 10,000 times. In a normal situation when species die their descendants through evolutionary process replace them. Also, the better-adapted relatives replace organism that are poorly adapted and less competitive. An instance is the replacement of the hypohippus by the modern-day horse [6]. In an undisturbed ecosystem single species go into extinct once in a decade. In this century, however, human impacts on populations and ecosystems have accelerated the rate causing hundreds and thousands of species and sub-species to go extinct every year. The major causes of extinction are habitat loss/fragmentation, illegal hinting, pollution [7], and the introduction of exotic species such as the introduction of the nypa palms in the Niger delta. In the past there has been some prominent extinctions such as the passenger pigeon, the dodo bird, and the pygmy mouse of south America [8]. The gradual decline in biodiversity has therefore, made several international agencies to come together to make some proclamations aimed at resolving this problem. To ensure the safety and well-being of nature’s resources, protected areas were established in species rich areas all over the world. Protected areas are areas set aside to protect and maintain biological or cultural diversity using legal instruments [9].

Categorization of protected areas

Protected areas are categorized into the following:

i. Ecological reserves and wilderness areas

ii. National parks

iii. Natural monuments and archeological sites

iv. Habitat and wildlife management areas

v. Cultural, scenic landscapes or recreation areas

There has been steady increase of protected areas all over the world after the first park (Yellowstone National Park) was established in the US in 1872 [10]. The growth of parks most especially in the tropics has equally been on the rise since the 1950s. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has in the past developed a conservation strategy to maintain ecological processes, preserve genetic diversity and ensure sustainability [11]. The concerted efforts of these world bodies have led to more than 530 million ha (nearly 4% of the earth’s land) to be designated as parks and wildlife refuge. According to the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) North and Central America have the largest fraction of all protected land i.e., 33% or nearly 10% of their land area is designated for protection of any continent [12]. Also, the largest protected area is in the tropical dry forests and savannas. Biodiversity hotspots are also found in Africa and the temperate deciduous forest in North America and Europe.

In Africa some countries have already developed good plans to protect 10% of their land areas. These countries include Tanzania, Rwanda, Botswana, Benin, Senegal, Central African Republic, and Zimbabwe. Establishment of protected areas has been a good idea, but recently it is generating controversy between conservationist and social scientist. This is because most people especially in developing countries see parks as the policy of government to usurp their resources and land right. This can be traced to the original concept of parks, which was for the purpose of its aesthetic, educational and recreational values without much consideration for the land ownership [13]. The landowners feel that it is a government idea to take away their socio-economic, cultural, ancestral, and spiritual, rights. The use of force by government to evict landowners is not taken lightly in many places. For instance, in Thailand the forceful ejection of the people from their land led to the deliberate setting of fire to the forest as well the poisoning of animals that strayed into their village.

Similarly, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo some great apes were slaughtered because of angers that originated from a confrontation between the local people and park rangers. Because of these skirmishes in host communities’ bodies such as World Bank, USAID, IUCN, WWF, and other NGOs have all called for people-centered conservation programme to reduce the anger of local people [14]. However, there is variety of opinions concerning whether more land should be protected (UNEP) or given up for agriculture (IUCN). This disagreement negatively affects local community because it is a volatile topic. A school of thought believes keeping more land for conservation with little human interference is the best option [15] while others believe all areas should be open to human use i.e., “the use advocate” [16-18]. In the face of these disagreements more people get displaced for the purpose of protection leading to more discontent [19] while more people still face the risk of more displacement from their ancestral land [20]. According to [21] the major impoverishment risks of local people include landlessness, joblessness, homelessness, marginalization, increased morbidity and mortality, loss of access to common property and social disarticulation, which is more common in Africa.

The Niger delta

The Niger Delta is situated in the southern part of Nigeria and makes a quarter of the population of Nigeria. The Niger Delta wetlands covers over 11, 020km2, which is 12% of Nigeria’s surface area. It is an area that is rich in natural resources most especially crude oil. It also a biodiversity hotspot [22]. It is among 200 global ecoregions classified as critically endangered by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). It is also the second most sensitive environment in Africa. The largest mangrove forest in Africa and the Atlantic is found in this region. Conservation of its resources is important because of the vulnerability of the area to global warming such as sea level rise leading to flooding and erosion. There is also a fear for future land tremors and earthquake because of seismic activity during oil and gas exploration [23].

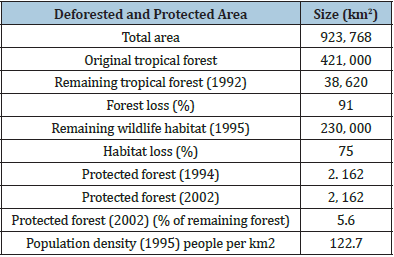

Conservation effort in Nigeria started in 1899 when the first forest reserve was established [24]. By 1939, most of the existing reserves in Nigeria have been created [25]. The original policy was to conserve 25% of the total land area, but rather only 10% was achieved. There are thirteen (13) game reserves and six (6) national parks in Nigeria. Two of these parks are situated in the Niger Delta area, namely: the Cross River National Park (CRNP) and the Edo National Park. There are 70 protected area in the Niger Delta. They are distributed as follows: Strict nature reserve (1), national parks (2), game reserve (4) and forest reserve (63). Despite the already established protected area in the Niger Delta there are still biodiversity decline due to anthropogenic activities such as farming, deforestation and developmental activities [26]. These activities have made the establishment of more protected areas difficult as shown in (Table 1). This study is based on determining the perception of people concerning protected areas in the Niger Delta. We thus hypothesize that the establishment of protected area is not bad for the local people. Thus, the objective of the study is to compare the perception of the people about the establishment of protected areas [27-30].

Table 1: Deforestation and protection assessment in Nigeria [27-29].

Materials and Methods

Description of study area

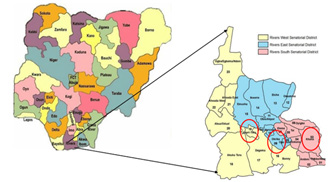

Three towns were sampled they include: Okrika (4°43N and 7°050E), Buguma ((4°45N and 6°53E) and Bori (4°68N and 7°37E). Okrika is one of the hosts by water bodies to the Port Harcourt Refinery. It is an island community surrounded by water bodies. It has rich supply of mangrove forest. the major occupation of the people is fishing. Buguma, on the other hand is also a community surrounded by water and has vast mangrove forest. Part of its water body was sand filled to create room for building houses for the people. The major occupation of the people is fishing. Bori is the headquarters of the Ogoni Kingdom, it has numerous oil wells with many cases of oil spillages recorded over the years. It also has large quantity of mangrove forest and other biodiversity [30] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Map of study area showing the three communities of Buguma, Okrika and Bori in Rivers State, Nigeria.

Sample collection

The study is survey research that involve the administration of 100 structured questionnaires. The questionnaires were distributed randomly in some settlements in the three communities of Bori, Okrika and Buguma. Oral interviews were also conducted to get direct information from the people, which is likened to be interactive forum where information on social issues or land tenure systems are derived [31]. During the interviews welfare conditions of the people were also derived. This include their natural resource utilization, demographic attributes of household (age, gender, ethnicity and education status), economic status (ownership of properties e.g., house) and income of household (revenue generating venture, labor, trade or business) [32,33]. This is because these items have a role to play in the perception of the people and would determine whether they will like protected area or not.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire contained thirteen (13) questions in all. But the key questions analyzed include: (1) what is the major occupation of the people? (2) what is the reason(s) for hunting/ farming, (3) what are the ways to stop over hunting and (4) will you want the establishment of parks in your community?

Statistical analysis

An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine whether there was a significant difference between the number of respondents that filled the questionnaire. The data was first log transformed to ensure that they were normal, and the variances were equal [34]. Tables and bar graphs were then used to illustrate the significance and difference in the various response of the people in the three communities. All analyses were done in [35].

Result

Summary responses to questionnaire questions from the three communities are illustrated in graphs and tables below.

Occupation of the people

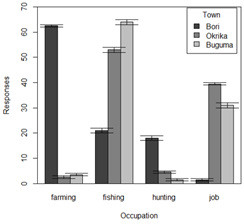

Figure 2: Occupations of the people sampled in the three different communities in Rivers State, Nigeria.

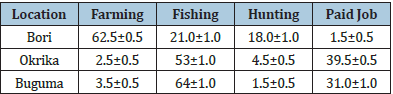

Table 2: Mean (±SE) number of responses on the occupation of the people in local communities in Rivers State, Nigeria.

The ANOVA result indicate that there is significant difference in the occupation of the people from the three communities (F3,20=3.41, P=0.04, (Table 2 & Figure 2). Tukey test shows fishing and hunting as the two key occupations (hunting-fishing -38.000000 -71.56941 -4.430588, P=0.023).

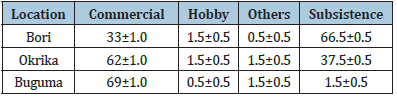

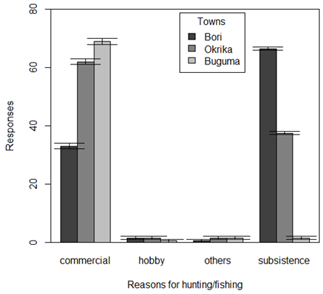

Reasons for hunting and fishing

The ANOVA result indicate that there is significant difference between the reasons for hunting (F3,20=14.74, P=0.001). Commercial (33±1.0-69±1.0) and subsistence (1.5±0.5-66.5±0.5) had the highest responses. The least responses are hobby and others (Table 3 & Figure 3).

Table 3: Mean (±SE) number of responses on the reasons for over hunting and fishing in some communities of Rivers State, Nigeria.

Figure 3: Reasons given by the people for hunting and fishing in some communities in Rivers State, Nigeria.

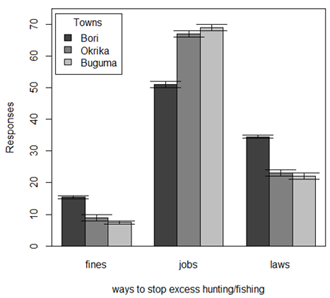

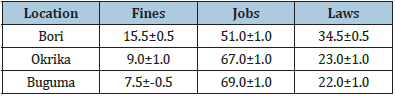

Ways to stop over hunting and fishing

The ANOVA result indicate that there is significant difference between different ways of stopping over hunting and fishing (F2,15=94.38, P=0.001, (Table 4 & Figure 4)). Majority of responses is for provision of jobs (51.0±1.0-69.0±1.0) while the least is for fines (7.5±-0.5-15.5±0.5).

Figure 4: Ways to stop over hunting and fishing in some communities in Rivers State, Nigeria.

Table 4: Mean (±SE) number of responses on the reasons for over hunting and fishing in some communities of Rivers State, Nigeria.

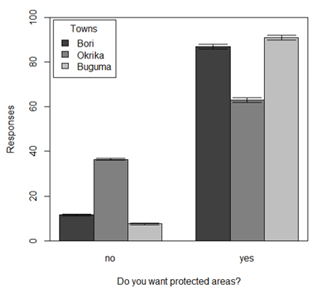

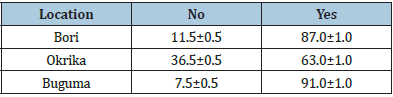

Do you want protected areas?

The ANOVA result indicate that there is significant difference between responses to the establishment of parks (F1,10=59.96, P=0.0001). In all an average of 80 persons said they are in support of the establishment of protected areas while 19 said they were not in support (Table 5).

Comparison of responses between communities

In terms of communities the results indicate that more persons in Bori indicated that they were farmers and sell their crops for feeding and income while more in Buguma indicate that they are into fishing, which they mostly sell to make money (Figure 2 & 3). Furthermore, more of those interviewed in Buguma and Okrika said provision of jobs will reduce over exploitation of natural resources (Figure 4). More persons in Buguma and Bori wanted the establishment of protected area as compared to those in Okrika (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Responses of people towards the establishment of protected areas in some communities in Rivers State, Nigeria.

Table 5: Mean (±SE) number of responses on the establishment of protected areas in some communities in Rivers State, Nigeria.

Discussion

Fishing is the most dominant occupation (Figure 2) because most communities in the Niger Delta area are surrounded by rivers [36] and despite the impact of pollution on the water body [37] they still serve as a major source of livelihood for the people as compared to the land that has been converted to construction sites or devastated by pollution. Although farming activities do occur in a small way, but most persons have sold their lands for development projects such as houses, roads, and industries. (Figure 2) also reveal that a handful of people are engaged in paid or white-collar jobs. Because of poverty and lack of jobs people tend to over exploit their resources for the purpose of feeding their families and selling some of the proceeds for income. This is because food security is at the heart of most indigenous African community [38].

Furthermore, many persons interviewed suggested that provision of jobs and the promulgation of laws are two policy tools that can help to stop the over exploitation of the natural resources. They said that if people are meaningfully engaged, they will not have time to plunder the resources in their environment. On the question of establishing protected areas majority answered in the affirmative, which agrees with the findings of [39] in a study of protected area in Myanmar where most people interviewed agreed to the establishment of a buffer zone. However, in our study, the reason for acceptance is because many interviewed feels that their environment had been so devastated by both private and corporate bodies to the extent that the only way out would be the protection of the remaining land from further damage for it to benefit present and future generations.

Table 1 shows that 91% of forest had been removed. For instance [40], study showed that between 1986-2003 >21kha of mangrove forest was removed from the Niger Delta region mainly because of wood extraction. The stem of red mangrove (Rhizophora species) is used for firewood by local inhabitants. Other causative factors of forest degradation are clearing of forest for the purpose of building houses for the rising population, poverty, and lack of jobs. Poverty has pushed many into embarking on reckless hunting of animals for food. Only 0.2% of forest is protected (Table 1), which is a low figure and not too good for species conservation in the region. The presence of two national parks in the region has not reversed biodiversity loss. A major cause is lack of local support for the conservation of the forest [41]. He further revealed that the support for forest protection is dependent on its benefit to the people. He also revealed that the fear of losing agricultural land and other land rights is a major factor of resistance to protection.

Many agreed that excessive hunting and fishing can be reduced if people are provided with paid jobs [42] as well social amenities [43]. They said since the jobs will provide money for their survival they will embark less on farming and fishing as means of survival. However, others believe that laws will assist in restrict the intrusion of people into the forest [44]. Although, majority embark on hunting and fishing for subsistence and for commercial purpose (Figure 2). Majority prefer the establishment of protected area (Figure 5) but expressed fear of the loss of their land, which may be like what they had passed through in the hands of oil industries, who over the years exploited their land, polluted it and then abandoned it. This action is what often leads to the opposition of conservation efforts in many communities (e.g., [41]). Therefore, when there are no benefits, the people take the laws into their own hands by intruding into the forests to exploit its resources in a reckless manner. For example, in East Africa it was observed that the expansion of parks, game reserves and protected areas free from human presence is generally accompanied by a decline in wildlife population [45]. This study therefore implies that a win-win ecological strategy is the best option for protection where both the environment and the people are jointly put into the conservation plan. This study also found out that fishing is the major occupation of the coastal communities (Okrika and Buguam) whereas those with fewer rivers and more land space engage in farming (e,g., Bori). The importance of jobs as a solution to over exploitation was also more prominent in Okrika, which is one of the hosts to a major refinery, the Port Harcourt Refinery. Persons interviewed in Okrika has the least support for the establishment of protected are probably because of the limited land in the area.

Conclusion

The establishment of protected areas is a good in conserving our natural resources, but our study has shown that it is necessary for the people to be carried along so that they will be the custodians of the safety of the environmental resources. In addition, government should also provide jobs for the teeming youths who are roaming around aimlessly. They can also invest in agriculture, where part of the protected land can be used for crop or animal farming to reduce idleness in our communities, this is because lack of meaningful engagement breeds other anti-social vices that are inimical to the well-being of the society at large.

References

- Kideghesho JR (2009) The potentials of traditional African cultural practices in mitigating overexploitation of wildlife species and habitat loss: experience of Tanzania. International Journal of Biodiversity Science & Management 5(2): 83-94.

- Corlett RT (2020) Safeguarding our future by protecting biodiversity. Plant Diversity 42(4): 221-228.

- Marselle MR, Hartig T, Cox DT, de Bell S, Knapp S, et al. (2021) Pathways linking biodiversity to human health: A conceptual framework. Environment International 150: 106420.

- Garibaldi LA, Oddi FJ, Miguez FE, Bartomeus I, Orr MC, et al. (2021) Working landscapes need at least 20% native habitat. Conservation Letters 14(2): e12773.

- Bax N, Sands CJ, Gogarty B, Downey RV, Moreau CV, et al. (2021) Perspective: increasing blue carbon around Antarctica is an ecosystem service of considerable societal and economic value worth protecting. Global Change Biology 27(1): 5-12.

- Janis CM, Damuth J, Theodor JM (2002) The origins and evolution of the North American grassland biome: the story from the hoofed mammals. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 177(1-2): 183-198.

- Singh V, Shukla S, Singh A (2021) The principal factors responsible for biodiversity loss. Open Journal of Plant Science 6(1): 011-014.

- Ceballos G, Ehrlich AH, Ehrlich PR (2015) The annihilation of nature: human extinction of birds and mammals. JHU Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

- Benidickson J, Paterson A (2017) Biodiversity, protected areas and the law. In Routledge Handbook of Biodiversity and the Law, Oxfordshire, England, UK, pp. 42-59.

- Smith DW, Bangs EE (2009) Reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park: history, values, and ecosystem restoration. Reintroduction of top-order predators. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, New Jersey, USA, pp. 92-125.

- IUCN (1980) World Conservation Strategy. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN (World Conservation Union).

- Sierra R, Campos F, Chamberlin J (2002) Assessing biodiversity conservation priorities: ecosystem risk and representativeness in continental Ecuador. Landscape and Urban Planning 59(2): 95-110.

- Zube EH (1995) Greenways and the US national park system. Landscape and Urban Planning 33(1-3): 17-25.

- Brown K (2003) Three challenges for a real people‐centred conservation. Global Ecology and Biogeography 12(2): 89-92.

- Kramer RA, van Schaik CP (1997) Preservation paradigms and tropical rain forests. In: Kramer RA, van Schaik CP, et al. (Eds.), Last stand: Protected areas and the defense of tropical biodiversity, Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Pimbert MP, Pretty JN (1997) Parks, people and professionals: putting ‘participation’ into protected area management. Social Change and Conservation 16: 297-330.

- Janzen W (1994) Old Testament ethics: A paradigmatic approach. Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville, Kentucky, USA.

- Wood D (1995) Conserved to death: Are tropical forests being overprotected from people? Land Use Policy 12(2): 115-135.

- Cernea MM (2002) For a new economics of resettlements: a sociological critique of the compensation principle. In: Cernea MM, Kanbar R (Eds.), An exchange on the compensation principle in resettlement. A working paper, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA.

- Geisler C (2001) Your Park, My Poverty: The growth of Greenlining in Africa. Paper presented at a Cornell University Conference on Displacement.

- Cernea MM, McDowell (2000) Risks and reconstruction: experiences of resettlers and refuges. World Bank, Washington, DC, USA.

- NDES (1997) Niger Delta Environmental Survey: biodiversity, Phase 1 Report.

- Nwankwoala HO, Orji OM (2018) An overview of earthquakes and tremors in Nigeria: occurrences, Distributions and Implications for Monitoring. International Journal of Geology and Earth Sciences 4(4): 56-76.

- Anadu PA (1987) Progress in the conservation of Nigeria’s wildlife. Biological Conservation 41(4): 237-251.

- NEST (1991) Nigeria’s threatened environment: a national profile NEST, Ibadan, Nigeria.

- Numbere AO (2021) Impact of Urbanization and Crude oil exploration in Niger Delta mangrove ecosystem and its livelihood opportunities: a footprint perspective. In Agroecological Footprints Management for Sustainable Food System, Springer, Singapore, pp. 309-344.

- Naughton-Treves L, Weber W (2001) Human dimensions of the African rain forest. In: Webber W, White LTJ, et al. (Eds.), African Rain Forest Ecology and Conservation.

- Perrings C, Edgar E (2000) The economics of biodiversity conservation in Sub-saharan Africa: mending the Ark. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, Cheltenham, UK.

- COMIFAC (Conference des ministres en charge des forets de l’ Afriqu Centrale) (2002) Position commune des ministers de la sous-region Afrique Centrale pour RIO + 10. Yaounde, Cameroon.

- SPDC (1999) EIA of Belema gas injection and oil field development project, pp. 9-10.

- Becker DR, Harris CC, McLaughlin WJ, Nielsen EA (2003) A participatory approach to social impact assessment: the interactive community forum. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 23(3): 367-382.

- Apaza L, Wilkie D, Byron E, Huanca T, Leonard W, et al. (2002) Meat prices influence the consumption of wildlife by the Tsimane'Amerindians of Bolivia. Oryx 36(4): 382-388.

- Wilkie DS, Starkey M, Abernethy K, Effa EN, Telfer P, Godoy R (2005) Role of prices and wealth in consumer demand for bushmeat in Gabon, Central Africa. Conservation Biology 19(1): 268-274.

- Logan M (2010) Biostatistical design and analysis using R: a practical guide, John Wiley and Sons, England.

- R Development Core Team (2013) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Okolo‐Obasi EN, Uduji JI, Asongu SA (2020) Strengthening women's participation in the traditional enterprises of sub‐saharan Africa: The role of corporate social responsibility initiatives in Niger delta, Nigeria. African Development Review 32(1): S78-S90.

- Numbere AO (2018) The impact of oil and gas exploration: invasive nypa palm species and urbanization on mangroves in the Niger River Delta, Nigeria. In Threats to mangrove forests, Springer, Cham, pp. 247-266.

- Pereira LM, Cuneo CN, Twine WC (2014) Food and cash: understanding the role of the retail sector in rural food security in South Africa. Food Security 6(3): 339-357.

- Htun NZ, Mizoue N, Yoshida S (2012) Determinants of local people's perceptions and attitudes toward a protected area and its management: A case study from Popa Mountain Park, Central Myanmar. Society & Natural Resources 25(8): 743-758.

- James GK, Adegoke JO, Saba E, Nwilo P, Akinyede J (2007) Satellite-based assessment of the extent and changes in the mangrove ecosystem of the Niger Delta. Marine Geodesy 30(3): 249-267.

- Ite UE (1996) Community perceptions of the Cross River national park, Nigeria. Environmental Conservation 23(4): 351-357.

- Mao Y, He J, Morrison AM, Andres Coca-Stefaniak J (2021) Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: from the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Current Issues in Tourism 24(19): 2716-2734.

- Gross-Camp ND, Martin A, McGuire S, Kebede B, Munyarukaza J (2012) Payments for ecosystem services in an African protected area: exploring issues of legitimacy, fairness, equity and effectiveness. Oryx 46(1): 24-33.

- Wei F, Cui S, Liu N, Chang J, Ping X, et al. (2021) Ecological civilization: China's effort to build a shared future for all life on earth. National Science Review 8(7): 279.

- Galaty J (1999) Grounding pastoralists: law, politics, and dispossession in East Africa. Nomadic Peoples 3(2): 56-73.

© 2022 © Aroloye O Numbere. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)